CHAPTER VI

THE WOMAN WITH THE GUN

The women soldiers of Russia, the most amazing development of the revolution, if not of the world war itself, I am disposed to believe, will, with the Cossacks, prove to be the element needed to lead, if it can be led, the disorganized and demoralized Russian army back to its duty on the firing line. It was with the object, the hope, of leading them back that the women took up arms. Whatever else you may have heard about them this is the truth. I know those women soldiers very well. I know them in three regiments, one in Moscow and two in Petrograd, and I went with one regiment as near to the fighting line as I was permitted. I traveled from Petrograd to a military position “somewhere in Poland” with the famous Botchkareva Battalion of Death. I left Petrograd in the troop train with the women. I marched with them when they left the train. I lived with them for nine days in their barrack, around which thousands of men soldiers were encamped. I shared Botchkareva’s soup and kasha, and drank hot tea out of her other tin cup. I slept beside her on the plank bed. I saw her and her women off to the firing line, and after the battle into which they led reluctant men, I sat beside their hospital beds and heard their own stories of the fight. I want to say right here that a country that can produce such women cannot possibly be crushed forever. It may take time for it to recover its present debauch of anarchism, but recover it surely will. And when it does it will know how to honor the women who went out to fight when the men ran home.

The Battalion of Death is not the name of one regiment, nor is it used exclusively to designate the women’s battalions. It is a sort of order which has spread through many regiments since the demoralization began, and signifies that its members are loyal and mean to fight to the death for Russia. Sometimes an entire regiment assumes the red and black ribbon arrowhead which, sewed on the right sleeve of the blouse, marks the order. Regiments have been made up of volunteers who are ready to wear the insignia. Such a regiment is the Battalion of Death commanded by Mareea Botchkareva (the spelling is phonetic), the extraordinary peasant woman who has risen to be a commissioned officer in the Russian army.

Botchkareva comes from a village near the Siberian border and is, I should judge, about thirty years old. She was one of a large family of children, and the family was very poor. They had a harder time than ever after the father returned from the Japanese war minus one foot, but that did not prevent their number from increasing, and merely made the lot of Mareea, the oldest girl, a little more miserable. She married young, fortunately a man with whom she was very happy. He was the village butcher and she helped him in the shop, as they had no children. When the war broke out in July, 1914, Mareea’s husband marched away with the rest of the quota from their village, and she never saw him again. He was killed in one of the first battles of the war, and the only time I ever saw Botchkareva break down was when she told me how she waited long months for the letter he had promised to write her, and how at last a wounded comrade hobbled back to the village and told her that the letter would never come. He was dead—out there somewhere—and they had not even notified her.

“The soldiers have it hard,” she said, when her brief storm of tears was over, “but not so hard as the women at home. The soldier has a gun to fight death with. The women have nothing.”

For months Mareea Botchkareva watched the sufferings of the women and children of her village grow worse and worse. Winter killed some of them, winter and an unwonted scarcity of food. Typhus came along and killed more. The village forgot that it had ever danced and sung and was happy. Every family was in mourning for its dead. Mareea decided that she could not endure it to sit in her empty hut and wait for death. She would go out and meet it in the easier fashion permitted to men. That was the way, she explained to me, she joined the regiment of Siberian troops encamped near the village. The men did not want her, but she sought and got permission, and when the regiment went to the front she went along too.

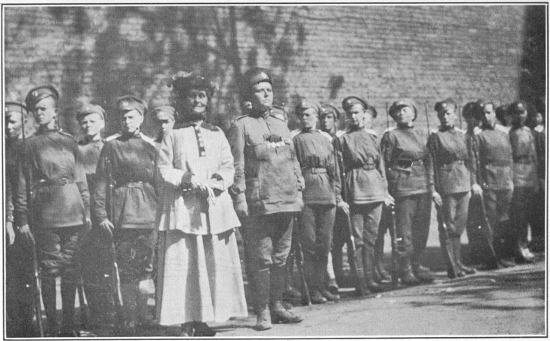

Mareea Botchkareva, Mrs. Emmeline Pankhurst and Women of “The Battalion of Death.”

She fought in campaigns on several fronts, earned medals and finally the coveted cross of St. George for valor under fire. She was three times wounded, the last time in the autumn of 1916, so badly that she lay in hospital for four months. She got back to her regiment, where she was now popular, and I imagine something of a leader, just before the revolution of February, 1917.

Botchkareva was an ardent revolutionist, and her regiment was one of the first to go over to the people’s side. Her consternation and despair were great when, shortly after the emancipation from czardom, great masses of the people, and especially the soldiers at the front, began to demonstrate by riots and desertions how little they were ready for freedom. The men of her regiment deserted in numbers, and she went to members of the Duma who were going up and down the front trying to stay the tide, and said to them: “Give me leave to raise a regiment of women. We will go wherever men refuse to go. We will fight when they run. The women will lead the men back to the trenches.” This is the history of Botchkareva’s Battalion of Death, or rather of how it came to be organized. The Russian war ministry gave her leave to recruit the women, gave her a barrack in a former school building, and promised her equipment and a place at the front. Many women in Petrograd, women of wealth and social position, took fire with the idea, raised money for the regiment, helped in the recruiting, some of them joining.

In an odd copy of an American newspaper that reached me in Russia I read a paragraph stating that the schoolgirls of Petrograd were forming a regiment under a man named Butchkareff, a lieutenant in the army. I don’t know who sent out that piece of news, but it lacked most of the facts. The women soldiers are not schoolgirls, and Botchkareva’s battalion has no men officers. Three drill sergeants, St. George cross men all of them, did assist in the training of the battalion while it remained in Petrograd. Other men drilled it behind the lines, but Botchkareva, and another remarkable woman, Marie Skridlova, her adjutant, commanded and led it in battle.

Marie Skridlova is the daughter of Admiral Skridloff, one of the most distinguished men of the Russian navy. She is about twenty, very attractive if not actually beautiful, and is an accomplished musician. Her life up to the outbreak of the war was that of an ordinary girl of the Russian aristocracy. She was educated abroad, taught several languages, and expected to have a career no more exciting or adventurous than that of any other woman of her class. When the war broke out she went into the Red Cross, took the nurses’ training and served in hospitals both at the front and in Petrograd. Then came the revolution. She was working in a marine hospital in the capital. She saw many of the horrors of those February days. She saw her own father set upon by soldiers in the streets, and rescued from death only because some of his own marines who loved him insisted that this one officer was not to be killed.

Into the ward of the hospital where she was stationed there was borne an old general, desperately wounded by a street mob. He had to be operated on at once to save his life, and as he was carried from the operating room to a private ward the men in the beds sat up and yelled, “Kill him! Kill him!” It is unlikely that they knew who he was, but it was death to all officers in those days of madness and frenzy. Half unconscious from loss of blood, still under the spell of the ether, the old man clung to his nurse as a child to his mother. “You won’t let them kill me, will you?” he murmured. And Mlle. Skridlova assured him that she would take care of him, that he was safe.

The door opened and a white faced doctor rushed into the room. “Sister,” he gasped, “go for that medicine—go quickly.” Not comprehending she asked, “What medicine?” But he only pushed her towards the door. “Go, go!” he repeated.

She left the room, and then she saw and understood. Down the corridor a mob was streaming, a wild, unkempt, blood-thirsty mob, the sweepings of the streets and barracks. Quickly she threw herself across the door of the old general’s room. “Get back,” she commanded. “The man in that room is old and wounded and helpless. He is in my care, and if you harm him it must be over my body.”

Incredible as it seems this girl of twenty was able for forty minutes to hold the mob at bay. When guns were pointed at her she told the men to fire through the red cross that covered her heart. They did not shoot, but some of the most brutal struck her down, and then held her helpless while others rushed into the room and hacked and beat the old man to death. When the nurse fought her way to his side he was breathing his last. She had time to whisper a prayer, and to make the sign of the cross above his glazing eyes. Then she went home, took off her Red Cross uniform, and said to her father: “Women have something more to do for Russia than binding men’s wounds.”

When Botchkareva’s Battalion of Death was formed Marie Skridlova determined to join it. Admiral Skridloff, veteran of two wars, iron old patriot, went with her to the women’s barracks and with his own hand enrolled her in the Russian army service. In the regiment of which this girl was adjutant I found six Red Cross nurses who were through with nursing and had gone out to die for their unhappy country. There was a woman doctor who had seen service in base hospitals. There were clerks and office women, factory girls, servants, farm women. Ten women had fought in men’s regiments. Every woman had her own story. I did not hear them all, but I heard many, each one a simple chronicle of suffering or bereavement, or shame over Russia’s plight.

There was one girl of nineteen, a Cossack, a pretty, dark-eyed young thing, left absolutely adrift after the death in battle of her father and two brothers, and the still more tragic death of her mother when the Germans shelled the hospital where she was nursing. To her a place in Botchkareva’s regiment and a gun with which to defend herself spelled safety.

“What was there left for me?” sighed a big Esthonian woman, showing me a photograph she wore constantly on her heart. It was a photograph of a lovely child of five years. “He died of want,” said the woman briefly. “His father is a prisoner somewhere in Austria.”

There was a Japanese girl in the regiment, and when I asked her her reason for joining she smiled, and in the evenly polite tone that marks her race, replied: “There were so many reasons that I prefer not to tell any of them.” One twilight I came on this girl sitting outside with the little Polish Jewess with whom she bunked. The two sat perfectly motionless on a fallen tree, watching a group of soldiers gathered around a fire. In their silent gaze I read a malevolence, a reminiscence so full of concentrated loathing that I turned away with a shudder. I never asked another woman her reason for joining the regiment. I was afraid it might be more personal than patriotic.

I do not believe, however, that this was the case with the majority. Mostly the women were in arms because they feared and dreaded the further demoralization of the troops, and they believed fervently that they could rally their men to fight. “Our men,” they said, “are suffering from a sickness of the soul. It is our duty to lead them back to health.” Every woman in the regiment had seen war face to face, had suffered bitterly through war, and finally had seen their men fail in the fight. They had beheld their men desert in time of war, the most dishonorable thing men can do, and they said, “Well then, there is nothing left except for us to go in their places.”

Did the world ever witness a more sublime heroism than that? Women, in the long years which history has recorded, have done everything for men that they were called upon to do. It remained for Russian men, in the twentieth century, to call upon women to fight and die for them. And the women did it.