CHAPTER X

THE HOMING EXILES—TWO KINDS

In a great, bare room, furnished with rows of narrow cots like a hospital, but with none of the crisp whiteness of the hospital, nor any of its promise of relief and restoration, a young man, propped with pillows, played on a concertina. He was white, emaciated, near the end of his young life. His eyes were like banked fires. He sat up in bed and in the intervals of coughing made the most wonderful music on that concertina, much more wonderful than I had ever dreamed the humble instrument could produce. The man was a true musician, and he had had many years of practice on his concertina, for it had been the one friend and solace of a solitary confinement which lasted nearly a dozen years. All around him in that bare room men lay in bed and listened to him. Some, however, were asleep. Even music could not break their weary rest. All were sick. Some were as near death as was the musician. Siberia had done its work with them. They had come home to die.

On a soap box, or its equivalent on a corner of the Nevski Prospect near the Alexander Theater, another young man stood and poured out a passionate speech to the crowd of soldiers, workmen and workwomen and idle boys who had paused to listen. The man was about thirty years old, and his clothes, it was plain to see, had never been purchased in Russia. They were American clothes of fair quality, and of that stylish cut possible to buy for twenty-five dollars in almost any department store. He wore a derby hat, tipped back on his head, a soft collar and a flowing tie. He talked rapidly and with many gestures, and the crowd listened with rapt interest to his speech. I, too, stopped to listen. “What is he saying?” I asked my interpreter.

“I don’t like to tell you,” she replied.

I insisted, and this is an almost literal translation of what that man said, on that Petrograd street corner, on an August day, 1917:

“You people over here in Russia don’t want to make a mistake of setting up the kind of a republic, of the kind of phony democracy like what they’ve got in the United States. I lived in the United States for ten years, and you take it from me, it’s the worst government in the world. They have a president who is worse than the Czar. The police are worse than Cossacks. The capitalist class is on top there just like they were in the old days in Russia. The working class is fighting them, and they are going to win. We are going to put the capitalists out just like you put them out here, and don’t you let any American capitalists come over here and help fasten on you a government like that one they still have in America. It’s the capitalists that plunged America into war. The working class never wanted it.”

These are two types of exiles which Russia has called back to her bosom since the revolution, both of which constitute another grave problem with which the distracted people are struggling. The sick ones, of whom there are thousands, came back and more of them are coming from Siberia at a time when food suitable for the sick is impossible to obtain. There was almost no milk. Eggs were hard to get and were not very fresh. Food of all kinds was getting scarcer every day. There was a fuel shortage that threatened to make all Russia spend a shivering winter, and what was to become of the sick was and still is a grave question. There is a great shortage of many medicines. If fighting is resumed the hospitals will be overcrowded. Doctors and nurses will be scarce. Yet the exiles continue to come back, the long stream from the remote villages continues to hold out its longing hands to the people back home, who cannot deny them. And nearly all the exiles come back sick and homeless and penniless. Russia must take care of those freed Siberian exiles, and I don’t quite see how she is going to do it, unless the miracle happens and they find a way of restoring peace and order in the land. In that case they can do anything. They can even deal with the kind of exile I heard talking on the Nevski.

Carlyle says that of all man’s earthly possessions, unquestionably the dearest to him are his symbols. They have the strongest hold on us without a doubt. At the time of the French revolution the sign and symbol of the old régime was the Bastille, that state prison in Paris which was the living grave of the king’s enemies, or of almost anybody who made himself unpopular with one of the king’s favorites. When the French people rose up in their might and swept the old régime out, the first thing they did, obeying a common impulse, was to tear down and destroy utterly the Bastille. In Russia the sign and symbol of the autocracy was the exile system, and particularly Siberia. The first thing the Russian people did when they rose up and dethroned the Romanoffs was to send telegrams to every political prison and to every convict village in Siberia that the prisoners and exiles were free. They sent orders to all the jailers and guards that the exiles were to be furnished with clothing and money and transportation to the railroads, and the railroads were directed to bring them back to Petrograd.

There is something to warm the coldest blood in the thought of what it must have meant to those poor desolate creatures, living in the hopeless isolation of Siberia, to have the door of the cell open one February day and hear the words,“You are free!” Sometimes the announcement was prefaced by words of unheard of friendliness and courtesy from wardens and jailers who had before been cruel and brutal task-masters. “Please forgive me if I have been over-zealous in my duties,” these men would say, and the prisoner would think that he had gone mad and was dreaming. Then the announcement would come, unbelievable in its wonder; the revolution had actually happened. The Czar was gone. The prisoner was free. They heard that news in the depths of mines, where men worked shackled and hopeless. They heard it in lonely villages near the Arctic Circle. They heard it in far lands, where homesick men and women toiled in sweatshops among aliens. They were free, and Mother Russia was calling them home again. I should think they would almost have died of joy at the tidings. No generous mind can wonder that Russia called back her children, all of them, without stopping to sort out the good and the bad, the well and the sick, the desirable and the undesirable. Or without stopping to calculate how she was going to take care of them when they got there.

But very early in the day it became evident that Russia was going to face a serious problem in her returned exiles. In the very first days of the revolution they opened all the prison doors in Petrograd as well as in other Russian cities, and let all the prisoners out. Among them were a number of politicals, and many of them immediately became public charges. They had no money, no friends, no home. The revolution had robbed them, in some cases, of all three. In some cases of long imprisonment the homes and friends had been taken from them by death. There had been a committee working secretly in behalf of political prisoners, and now this committee, with a group in the Red Cross, got together and formed a society which they call the Political Red Cross, the committee in charge of returned exiles. For they saw plainly that what had happened in the case of the Petrograd prisoners would be repeated on a large scale when the Siberian exiles and those from foreign lands returned. Another committee was formed in Moscow. They sprang up in various cities, co-operating with the Zemstvoes or county councils.

At the head of the work is Vera Figner, one of the most famous of the old revolutionists, almost the last survivor of the nihilism of the eighteen seventies. The Russians are said to lack organizing ability, but the work done by this committee under Vera Figner’s direction looks to me that once Russia gets a government that can govern and an army that will fight the people of Russia will organize a civilization that will teach Europe new things. The committee started with nothing, not even machinery to work with. There is no such thing in Russia as a charity organization society. Charity and benevolence there are, mostly of the old-fashioned type, “Under the patronage of her imperial highness, the Princess Olga,” or “the empress dowager.” There was no well-organized society of any kind to appeal to to help take care of some seventy-five thousand exiles hurrying home, an unknown number of them sick, another unknown number poor and homeless, and all of them strangers in a new Russia.

Vera Figner I saw in the Petrograd headquarters of the society. She is a matronly woman, looking less than sixty, although she must be older. She has a handsome face, with the deep, smoldering eyes of the revolutionist, but her smile is quiet and kind. Near her at the long committee table sat Mme. Kerenskaia, the estranged wife of the minister president Kerensky. She is an attractive young woman with dark eyes and abundant dark hair, who gives all of her time to the work of the exiles committee. Mme. Gorki is another woman of prominence who works with the committees, and Prince Kropotkin and his daughter, Mme. Lebedev, whose husband was in the government when I left, are also constant workers. The work was done through eight committees, one of which collected money, a great deal of money, too. Hundreds of thousands of roubles have poured in from all over Russia as well as from England, America, France. Another committee collects clothes, and they are much scarcer than money in Russia. A committee on home-finding also collects sanitarium and hospital beds wherever they are to be found. A reception committee meets the exiles and takes them to their various lodgings. A medical and a legal aid committee take care of their own sides of the work. All over Petrograd and Moscow they have established temporary lodgings and temporary hospitals for the cure of the returned sick and helpless. It was in such a refuge that I saw and heard the man with the concertina.

I had come to find Marie Spirodonova, one of the most appealing as well as the most tragic figures of the revolution of 1905-06. She was the Charlotte Corday of that revolution, for like Charlotte she, unaided by any revolutionary society, freed her country of one of the worst monsters of his time. She shot and killed the half-mad and wholly horrible governor of Tambosk. And like Charlotte she paid for that deed with her life. She lived indeed to return to Russia, but her span after that was short. Marie Spirodonova was in the last stages of tuberculosis when they brought her back to Russia. Ten years’ solitary confinement had done that for her. The first sentence of death, afterward commuted to twenty years’ exile, would have been shorter and more merciful. When I saw her, she was in bed, so wasted that she looked like a child. The flush of fever on her cheeks gave her a false look of health, and she looked almost as beautiful as on the day when she stood in the prisoner’s dock and told the judges how and why she killed the monster of a governor. Her voice was all but gone now, and it was in a hoarse whisper that she greeted me, and asked news of her one or two friends in America. I could stay only a few minutes, she was so weak. It is hardly possible that she still lives, although no news of her death has reached me.

Until the last breath she must have kept her iron will and indomitable spirit. Ten years in a solitary cell could not break that spirit, as the story of her release shows. When the first telegram came to the distant prison, where she and nine other women were confined, the names of only eight of them were specifically mentioned.

“But what about us?” wailed the two forgotten ones.

The warden of the prison perhaps did not entirely believe in the success of the revolution, and wanted to be on the safe side. “You stay,” he said.

“Then none of us will go,” said Marie Spirodonova, and they all stayed until the next day when another telegram arrived setting them all free. In the same spirit Spirodonova refused to leave her companions after they reached Petrograd. She was so famous, so sought after, that she could have chosen among a dozen hospitable homes, in the country, in the Crimea or the bracing mountains of the Caucasus. But she said she would not have anything her old prison mates did not have, so Marie Spirodonova, daughter of a general, and the concertina player, child of a peasant, die as they lived, revolutionists, spurning all the comforts of life, all the protection and security of home, all the plaudits of the world. They lived and died for Russia as surely as though they died on the battlefield.

Of the same type is the most celebrated exile of all, Catherine Breshkovskaia, the Babushka, or little grandmother of the revolution. They brought Babushka back to Petrograd in the first rush. They gave her a reception at the station such as no crowned head in Europe ever had, and they took her to the Winter Palace and told her that when the Czar moved out he left it to her. Babushka lived in the Winter Palace when she was in Petrograd, which was seldom. Most of the time she was touring rural Russia and trying to make her peasants understand what the revolution meant, and that they would make the country a worse place than it ever was before unless they stopped fighting to grab all the land in sight without any regard to right and justice. “I know them,” she said in a brief talk I had with her in the palace. “If I can only live long enough to reach them in numbers, I can deal with them. They have listened to a pack of nonsense, but I shall tell them better.”

Breshkovskaia is past seventy years old. She is growing very deaf, and her weight makes traveling difficult. Yet her mind is clear and vigorous, and when she makes a speech she manages somehow to call back the voice and the strength of a woman of forty. Spirodonova, Breshkovskaia, Kropotkin, Tschaikovsky and almost every one of the old revolutionists are eager adherents of the moderate program of the early provisional government, before the Bolsheviki crowded in with their cry of “All the power to the Soviets!” They want the war fought to a finish, and they want order restored in Russia. It is quite otherwise with another type of exile, and I am sorry to say some of this other kind were made in the United States of America.

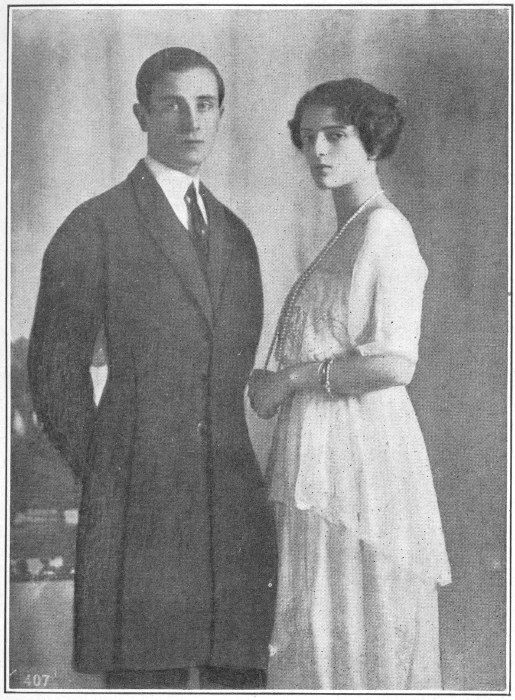

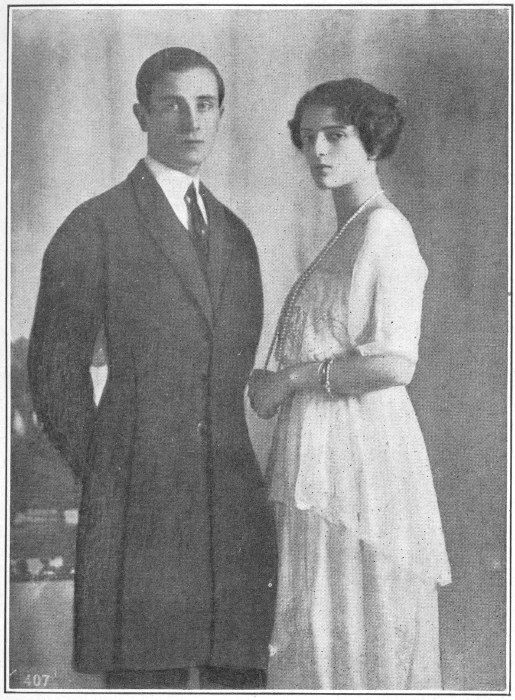

Prince Felix Yussupoff, at whose palace on the Moika Canal Rasputin

was killed, and his wife, the Grand Duchess Irene

Alexandrovna, niece of the late Czar.

In the boat in which I crossed the Atlantic last May there were three Russian men who had spent some years in America and were on their way back to Petrograd. These men were not exiles, but they had found Russia intolerable to live in and had gone to America, which had been so kind to them in a material way that they were able to go back to Russia in the first cabin of an ocean liner. All three were pronounced pacifists and one was a readymade Bolshevik. He was for the whole program, separate peace, no annexations or contributions, no sharing the government with the bourgeois, no compromise on anything. A real Bolshevik. And made on the east side of New York. This man used to talk to me on deck and in the saloon about how the Soldiers’ and Workmen’s Delegates were going to dictate terms of peace to the allies, and how the social revolution was going to spread all over the world, and especially all over America, and then he would hasten to assure me that he wasn’t nearly as radical as some of the Tavarishi I would meet in Russia, and he wasn’t. When we reached the Finnish frontier and stopped at Tornea for examination I had the pleasure of seeing all three of these men taken into custody by some remnant of authority existing in the army, and taken down to Petrograd under guard as men who had evaded military duty. My friend declared that nothing would ever induce him to put on a uniform or to fight. Not he. And the others rather less confidently echoed his defiance. Finally one of them said: “on the whole, I think I will enlist. They need educated men at the front to talk peace to them.” Thus at least one emissary of the Kaiser was contributed to poor, bleeding Russia by the United States.

Just one more case, because it is typical of many. This man was a real exile, and for eleven years he had lived in Chicago. Born in a small city of western Russia, he joined, when still a youth, what was known as the Bund, a socialist propagandist circle of Jewish young men and women. The youth’s parents, quiet, orthodox people, knew nothing of his activities, nor of the revolutionary literature of which he was custodian and which he had concealed in the sand bags piled up around the cottage to keep out the winter cold. On May 31, 1905, the Tavarishi, or comrades, in his town organized a small demonstration against the celebration of the Czar’s birthday. The next day the police began searching houses and making arrests among the youth of the town, and they found the books hidden in the sandbags. The boy fled, and found refuge in the next town. Money was raised, a passport forged and the youth finally got to England via Germany. He didn’t like England and in 1906 he crossed to the United States. He didn’t like the United States either, and his whole career in Chicago was a history of agitation and rebellion. He was one of the founders of a socialist Sunday school in Mayor Thompson’s town, where children of tender years are given a thorough education in Bolshevik first principles.

When the Russian revolution broke and Russian consuls all over the world advertised for exiles to be taken back to Russia’s heart, this man presented himself as one of the returners. He showed me the certificate issued by the Russian consulate in Chicago. It says that it was issued in accordance with the orders of the provisional government and records that the said —— —— was paid the sum of $157.25 and was given transportation from Chicago to Petrograd, via the Pacific Ocean and the Trans-Siberian railroad. At Vladivostock he received more money, and on his arrival in Petrograd he was given a small weekly allowance in addition to his free lodgings. He had a good time on the journey, he said. There was a band at most of the stations where the train stopped, crowds, flowers and much cheering. It was agreeable to get back to Petrograd also and be met by a committee. But the habit of hating governments was so settled in his system that within a week he was talking against the one that had paid his way back, and he was talking hard against the one which had taken him in and given him a free education and a job and a chance to establish a socialist Sunday school with perfect impunity. He was in with all the Bolshevik activities except one. He had no stomach for fighting. The spirit was willing but the flesh was weak. It got to a point where it was hard to be a Bolshevik in good standing and never do any gun work, so this exile determined to go back to Chicago. When I knew him he was haunting the committees and various ministries trying to persuade them to give him the money with which to return.

“You don’t think they can draft me into the American army, do you?” he asked me anxiously. “I am a Russian subject. I don’t see how they could do it legally.”

I don’t know how many men of this kind went back to Russia from the United States, but there were enough of them to be conspicuous, and the Russian radicals believe them to be far more reliable witnesses than the Root Commission, which made a remarkably good impression on the educated people but none at all on the Tavarishi. “Don’t you believe that the United States is in this war for democracy,” shouted one Nevsky Prospect orator. “The United States is just as imperialistic as England. You oughtta read what Lincoln Steffens and John Reed wrote about the United States and Mexico.” These men will do Russia all the harm they can, and then they will come back to America and do us all the harm they can. If I had my way they would go from Ellis Island, with all the rest of their kind still remaining here, to some kind of a devil’s island in the South Seas and be kept there until they died.