CHAPTER XV

THE HOUSE OF MARY AND MARTHA

On the afternoon of the day when Nicholas II., deposed emperor and autocrat of all the Russias, with his wife and children left Tsarskoe Selo and began the long journey toward their place of exile in Siberia, I sat in a peaceful convent room in Moscow and talked with almost the last remaining member of the royal family left in complete freedom in the empire. This was Elisabeta Feodorovna, sister of the former empress and widow of the Grand Duke Serge, uncle of the emperor. The Grand Duke Serge was assassinated, blown to pieces by a bomb, almost before the eyes of his wife, by a revolutionist on February 4 old style, 1905. He was killed when going to join the Grand Duchess in one of the churches of the Kremlin in Moscow. She rushed out and saw his mutilated remains lying in the snow. The Grand Duchess Serge had long been known as a noble and saintly woman, and her conduct following the horrible death of her husband perfectly illustrates her character. She besought the Czar to commute the death sentence passed upon the assassin, and when he refused she went to the prison where the wretched man waited his death, gained admission to his cell, and almost to the end prayed with him and comforted him. No children had ever been born to her, and after the event which cut the last tie that bound her to the life of royal pomp and glitter she retired from society and gave herself up to religion. As soon as possible she became a nun. Her private fortune, to the last rouble, investments, palaces, furniture, art treasures, jewels, motor cars, sables and other fine raiment were turned into cash and the money used to build a convent and to found an order of which she became the lady abbess. The Grand Duchess Serge literally obeyed the edict of Christ to the rich young man: “Sell all thou hast and give it to the poor.”

The Convent of Mary and Martha, of the Order of Mercy in Moscow, is a living token of her great sacrifice. Here for the past eight years she has lived and worked among her nuns, at least one of whom was a court lady, and many of whom are women from the intellectual classes. Some of the nuns were from humble households, for the order is perfectly democratic. Every one who enters the House of Mary and Martha does so with the understanding that her life is to be spent in service, spiritual service such as Mary of the Gospels gave, and material service such as the practical Martha rendered her Lord. The somewhat dreamy and passive Russians will tell you that Elisabeta Feodorovna’s convent is one of the most efficient institutions in the empire, and they usually add: “They say she makes her nuns work terribly hard.”

When the days of revolution came, in February, 1917, a great mob went to the House of Mary and Martha, battered the gates open and swarmed up the convent steps demanding admission. The door opened and a tall, grave woman in a pale silver-gray habit and white veil stepped out into the porch and asked the mob what it wanted.

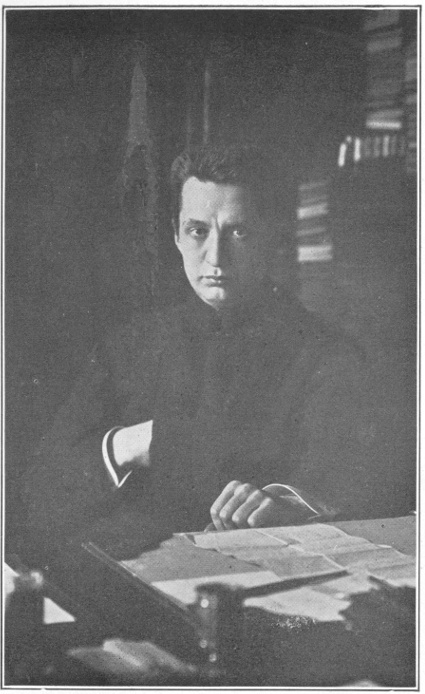

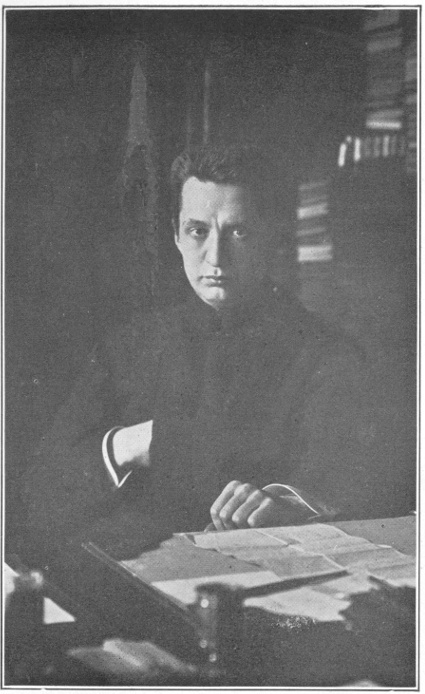

Alexander Feodorovitch Kerensky.

“We want that German woman, that sister of the German spy in Tsarskoe Selo,” yelled the mob. “We want the Grand Duchess Serge.”

Tall and white, like a lily, the woman stood there. “I am the Grand Duchess Serge,” she replied in a clear voice that floated above the clamor. “What do you want with me?”

“We have come to arrest you,” they shouted.

“Very well,” was the calm reply. “If you want to arrest me I shall have to go with you, of course. But I have a rule that before I leave the convent for any purpose I always go into the church and pray. Come with me into the church, and after I have prayed I will go with you.”

She turned and walked across the garden to the church, the mob following. As many as could crowd into the small building followed her there. Before the altar door she knelt, and her nuns came and knelt around her weeping. The Grand Duchess did not weep. She prayed for a moment, crossed herself, then stood up and stretched her hands to the silent, staring mob.

“I am ready to go now,” she said.

But not a hand was lifted to take Elisabeta Feodorovna. What Kerensky could not have done, what no police force in Russia could have done with those men that day, her perfect courage and humility did. It cowed and conquered hostility, it dispersed the mob. That great crowd of liberty-drunk, blood-mad men went quietly home, leaving a guard to protect the convent. It is probably the only spot in Russia to-day where absolute inviolability may be said to exist for any members of the hated “bourju,” as the Bolsheviki call the intellectual classes.

On the August day when I rang the bell of the convent’s massive brown gate I did not really know that I was to see and speak with the grand duchess. Mr. William L. Cazalet, of Moscow, the friend who took me there, doubted very much whether I could be received thus informally, without a previous appointment. The gravity of the times, and especially the situation of the Romanoff family, placed the Grand Duchess Serge in a position of extreme delicacy, and Mr. Cazalet said frankly that he expected to find her living in strict retirement. The best he could promise, he said, was that I should see the convent, where one of his young cousins was a nun.

The convent, which is situated in the heart of Moscow, is a group of white stone and stucco houses built around an old garden and surrounded by a high white wall, over which vines and foliage ramble and fall. A key turned, the brown gate swung open to our ring and we stepped into a garden running over with the richest bloom. I remember the pink and white sweet-peas against the wall, the white madonna lilies that nodded below and the carpet of gay verbenas that ran along the pathway to the convent door. There were many old apple trees and a forest of lilacs, purple and white.

In her small room, combination of office and living room, we were received by the executive head of the convent, Mme. Gardeeve, for many years the intimate friend of Elisabeta Feodorovna. Like the grand duchess she had had a life full of tears and tribulation, in spite of her rank and wealth, and when the grand duchess took the veil she followed her example and became a nun. The business of the convent is transacted under her direction, and most ably, I was told. Efficiency and ability are written in every feature of Mme. Gardeeve’s fine face, in her crisp, clear voice and quick though graceful movements. Her enunciation was a joy to hear, an especial joy to me, for I have difficulty in understanding the rather indistinct French spoken by the average Russian. Mme. Gardeeve’s French was of that perfect kind you hear spoken in Tours more often than in Paris or elsewhere. I understood every word. Woman of the world to her finger tips, Mme. Gardeeve wore the picturesque habit of the order with the same grace that she would have worn the latest creation of the ateliers. She smiled and chatted with Mr. Cazalet, who is very well known in the convent, and was most kind and cordial to me. After a few minutes’ conversation my friend said to her that I had told him some extremely interesting things about public schools in America, and he wanted me to repeat them to her.

So I told her something about the extraordinary experiments that have been worked out in Gary, Indiana, and the work that was being done in New York and elsewhere to give children, rich and poor alike, the complete education they merit. As I talked she exclaimed from time to time: “But it is excellent! I find it admirable! The Grand Duchess should hear of this!”

I said hopefully that I would like very much to meet the Grand Duchess and she replied she thought it might be arranged. Not to-day, however, as the Grand Duchess’s time was completely filled. How long did I expect to remain in Moscow? A week? It could certainly be arranged, she thought. Meanwhile what would I like to see of the convent? Everything? She laughed and touched a little bell on the desk beside her. A little nun appeared and Mme. Gardeeve handed me over to her with orders that I was to see everything.

I saw a small but perfectly equipped hospital, with an operating room complete in all its details. The hospital had been devoted to poor women and children before the war. Now most of the wards are filled with wounded soldiers. I saw a room filled with blinded soldiers who were being taught to read Braille type by sweet-faced nuns. Blindness is bitter hard for any man, but for illiterates it must be blank despair. I saw a house full of refugee nuns from the invaded districts of Poland. I saw an orphanage full of slain soldiers’ children. I lingered long in the lovely garden where nuns were at work, some with their habits tucked up, among the potato rows, some pruning trees and hedges, some sweeping the gravel paths with besoms made of twigs, some teaching the orphan girls to embroider at big frames, to knit and to sew. They made a fascinating picture, and I could hardly leave them even to see the church, which is one of the most beautiful small gems of architecture to be found in Europe. I never really saw that church at all, as it turned out, for just as we entered and I was getting a first impression of its blue and white and gold beauty, a messenger hastily opened the door and said that the Grand Duchess wanted to see me.

We went back to the convent and I was taken to a tiny parlor, which is the private retreat of the Lady Abbess. It is not much bigger than a hall bedroom, and it gave the same general impression of blue and white and gold that one sees throughout the place. There were many books bound in the lapis blue which seems to be the Grand Duchess’s favorite color; a few pictures, mostly of the Madonna and Child; some small tables, one with Stephen Graham’s book, “The House of Mary and Martha,” held open upon it by a piece of embroidery carelessly dropped. There were easy chairs of English willow with blue cushions, and a businesslike little desk crammed with papers. Everywhere, in the window, on tables and the desk, were bowls and vases of flowers. Every room in the place, in fact, was filled with flowers.

The door opened and the Grand Duchess came in with a radiant smile of welcome and a white hand outstretched. “I am so glad to find that I had time to meet you to-day, Mrs. Dorr,” she said, in a rarely sweet voice.

“Your highness speaks English?” I exclaimed in surprise, and she replied, waving me to a comfortable armchair: “Why not? My mother was English.”

I had forgotten for the moment that the Grand Duchess and her younger sister, the former Empress of Russia, were daughters of the Princess Alice of England and granddaughters of Queen Victoria. Russia seemed to have forgotten it also and to have remembered only that the father of these women was the Grand Duke of Hesse and the Rhine. The Grand Duchess added when we were seated that when she was a child at home they always spoke English to their mother, if German to their father. “I welcome an opportunity to speak English, because if one is wholly Russian, as I am, and especially if one is orthodox, he hears little except Russian or French.” Then she said, with another radiant smile: “Tell me what you think of my convent.”

I told her that I felt as though I had stepped back into the glowing and romantic thirteenth century.

“That is just what I wanted my convent to be,” she replied, “one of those busy, useful medieval types. Such convents were wonderfully efficient aids to civilization in the middle ages, and I don’t think they should have been allowed to disappear. Russia needs them, certainly, the kind of convent that fills the place between the austere, enclosed orders and the life of the outside world. We read the newspapers here, we keep track of events and we receive and consult with people in active life. We are Marys, but we are Marthas as well.”

The Grand Duchess’s interest in the outside world is patent. She asked me eagerly to tell her how things were going in Petrograd, and her face saddened when I told her of the riotous and bloody events I had witnessed during the days of the July revolution, scarcely past. “Times are very bad with us just now,” she said, “but they will improve soon, I am sure. The Russian people are good and kind at heart, but they are mostly children—big, ignorant, impulsive children. If they can find good leaders, and if they will only realize that they must obey their leaders, they will emerge from this dreadful chaos and build up a strong, new Russia. Have you seen Kerensky, and what do you think of him?”

I replied rather cautiously. Like every one else, I still hoped that Kerensky would succeed in getting his released giant back into its bottle, and I did not want to unsettle any one’s confidence in him even to the extent of an expressed doubt. Kerensky, I told her, was greatly admired and liked, and I hoped he might prove the strong leader Russia needed in her trouble.

“I hope so,” replied the last of the Romanoffs, “I pray for him every day.”

The bells of the little church chimed the hour softly, and the Grand Duchess paused to cross herself devoutly. “I want to hear about those wonderful public schools of yours,” she said, “but first tell me what America is doing in war preparation.”

As I talked she listened, nodding and smiling as if immensely pleased. The great airplane fleet in course of construction seemed to amaze and delight her, and when I told her of the conservation of the food supply and the restriction of the manufacture of alcohol she fairly glowed. “America is simply stupendous,” she exclaimed. “How I regret that I never went there. Of course I never shall now. To me the United States stands for order and efficiency of the best kind. The kind of order only a free people can create. The kind I pray may be built some day here in Russia.” And then she made her one allusion to the deposed Czar. I did not know that at that minute the Czar was on his way to Siberia, but it is very probable that she knew it. She said: “I am glad you are going to protect your soldiers from the danger of the drink evil. Nobody can possibly know how much good the abolition of vodka did our soldiers and all our people. I think history should give the Emperor credit for his share in that act, don’t you?” I agreed that the Emperor should receive full credit for what he did, and I spoke with all sincerity.

Elisabeta Feodorovna kept me for nearly three-quarters of an hour talking to her about the Gary schools, which she is eager to see in Russia; about American women and their part in the war, and about welfare work for children, especially for tubercular and anemic children. “It is wonderful,” she said with a sigh. “I can scarcely help envying you sinfully. Think of a great, young, hurrying nation that can still find time to study all these frightful problems of poverty and disease, and to grapple with them. I hope you will go on doing that, and still find more and more ways of bringing beauty into the lives of the workers. How can you expect workmen who toil all day in hot, hideous factories or on remote farms, with nothing in their lives but work and worry, to have beauty in their souls?”

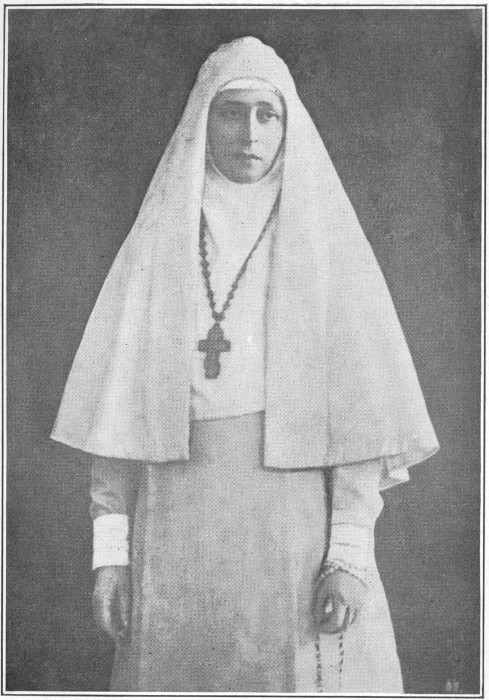

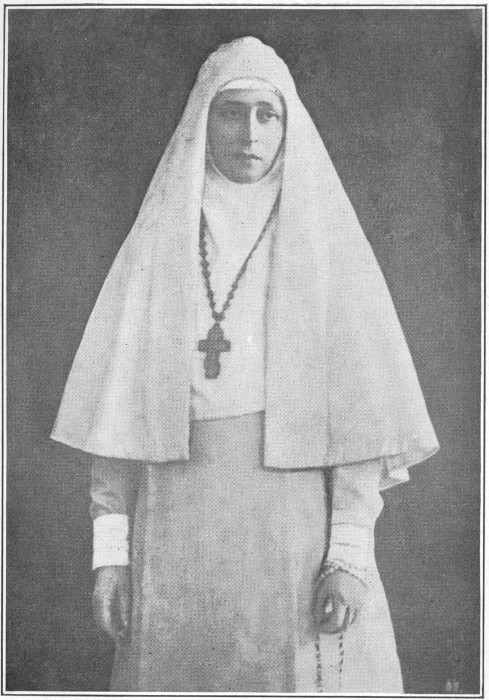

The Grand Duchess Elizabeta Feodorovna, sister of the late Czarina,

and widow of the Grand Duke Serge (who was assassinated

during the Revolution of 1905), now Abbess of the

House of Mary and Martha at Moscow.

She wanted eagerly to know about the women soldiers, and said that she greatly admired their heroism. What was their life in camp like, and were they strong enough to stand the hardships? The Grand Duchess Serge is a good feminist and she agreed with me that in Russia’s crisis, as in the situation in all countries created by the war, it had been completely demonstrated that women would have henceforth to play a rôle equally important and equally prominent as that of men.

They would have to share equally with men in the successful operation of the war whether on the battlefield or behind the lines. She had always had a special devotion to Jeanne d’Arc and believed her to have been inspired by God. Other women also had been called of God to do great things.

“I am glad you like my convent,” she repeated as we parted. “Please come again. You know that it does not belong to me any more, but to the Provisional Government, but I hope they will let me keep it.”

I hope they will. The House of Mary and Martha, with the beautiful woman in it, is one of the things new Russia can least afford to lose.