CHAPTER III

THE JULY REVOLUTION

Every one who has read the old “Arabian Nights” will remember the story of the fisherman who caught a black bottle in one of his nets. When the bottle was uncorked a thin smoke began to curl out of the neck. The smoke thickened into a dense cloud and became a huge genie who made a slave of the fisherman. By the exercise of his wits the fisherman finally succeeded in getting the genie back into the bottle, which he carefully corked and threw back into the sea. Kerensky tried desperately to get the genie back into the bottle, and every one hoped he might succeed. Up to date, however, there is little to indicate that the giant has even begun materially to shrink. Petrograd is not the only city where the Council of Workmen’s and Soldiers’ Delegates has assumed control of the destinies of the Russian people. Every town has its council, and there is no question, civil or military, which they do not feel capable of settling.

I have before me a Petrograd newspaper clipping dated June 12. It is a dispatch from the city of Minsk, and states that the local soviet had debated the whole question of the resumption of the offensive, the Bolsheviki claiming that the question was general and that it ought to be left for the men at the front to decide. They themselves were against an offensive, deeming it contrary to the interests of the international movement and profitable only to capitalists, foreign as well as Russian. Workers of all countries ought to struggle against their governments and to break with all imperialist politics. The army ought to be made more democratic. This view prevailed, says the dispatch, by a vote of 123 against 79.

This is typical. In some cities the extreme socialists are in the majority, in others the milder Minsheviki prevail. In Petrograd it has been a sort of neck and neck between them, with the Minsheviki in greater number. But as the seat of government Petrograd has had a great attraction for the German agents, and they are all Bolsheviki and very energetic. Early in the revolution they established two headquarters, one in the palace of Mme. Kchessinskaia, a dancer, high in favor with some of the grand dukes, and another on the Viborg side, a manufacturing quarter of the city. Here in a big rifle factory and a few miles down the Neva in Kronstadt, they kept a stock of firearms, rifles and machine guns big enough to equip an army division.

The leader of this faction, which was opposed to war against Germany but quite willing to shoot down unarmed citizens, was the notorious Lenine, a proved German agent whose power over the working people was supreme until the uprisings in July, which were put down by the Cossacks. Lenine was at the height of his glory when the Root Commission visited Russia, and the provisional government was so terrorized by him that it hardly dared recognize the envoys from “capitalistic America.” Only two members of the mission were ever permitted to appear before the soviet or council. They were Charles Edward Russell and James Duncan, one a socialist and the other a labor representative. Both men made good speeches, but not a line of them, as far as I could discover, ever appeared in a socialist newspaper. In fact, the visit of the commission was ignored by the radical press, the only press which reaches 75 per cent of the Russian people.

In order to make perfectly clear the situation as it existed during the spring and summer, and as it exists to-day, I am going to describe two events which I witnessed last July. Both of these were attempts of the extreme socialists to bring about a separate peace with Germany, and had they succeeded in their plans would have done so. Moreover, they might easily have resulted in the dismemberment of Russia.

The 18th of June, Russian style, July 1 in our calendar, is a day that stands out vividly in my memory. For some time the Lenine element of the Workmen’s and Soldiers’ Council had planned to get up a demonstration against the non-socialist members of the provisional government and against the further progress of the war. The Minshevik element of the council, backed by the government, spoiled the plan by voting for a non-political demonstration in which all could take part, and which should be a memorial for the men and women killed in the February revolution, and buried in the Field of Mars, a great open square once used for military reviews. As the plan was finally adopted it provided that every one who wanted to might march in this parade, and no one was to carry arms. Great was the wrath of the Lenineites, but the peaceful demonstration came off, and it must have given the government its first thrill of encouragement, for events that day proved that the Bolsheviki or Lenine followers were cowards at heart and could be handled by any firm and fearless authority.

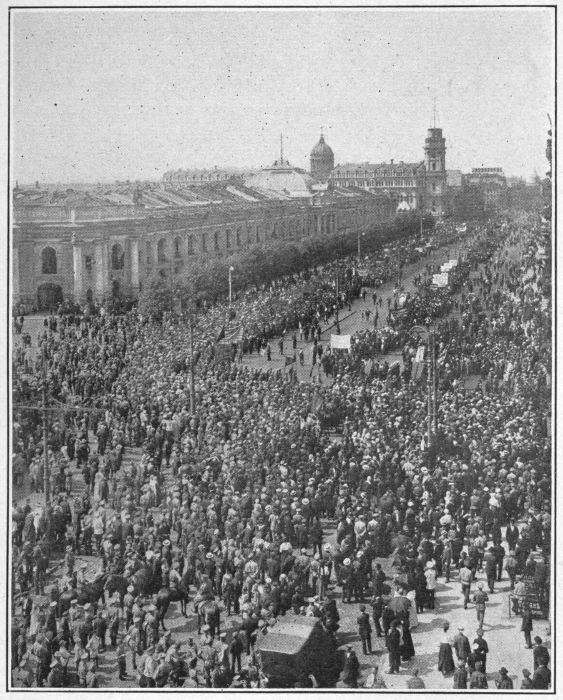

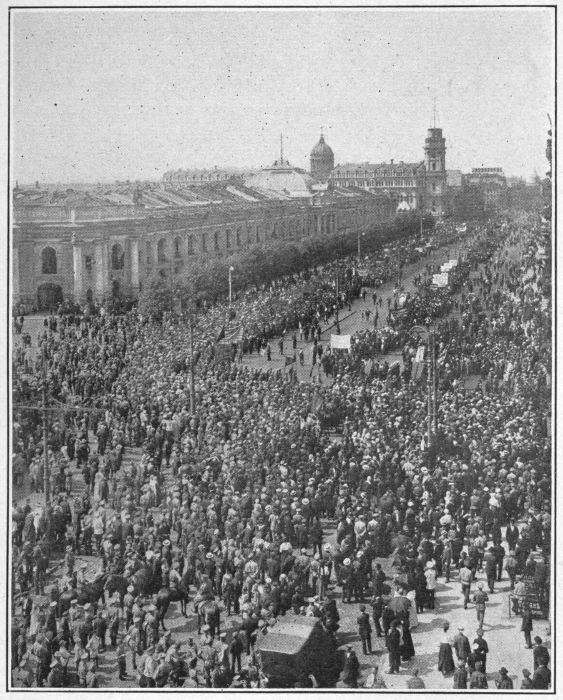

It was a beautiful Sunday morning, this eighteenth of June, when I walked up the Nevski Prospect, the Fifth avenue of Petrograd, watching the endless procession that filled the street. Two-thirds of the marchers were men, mostly soldiers, but women were present also, and a good many children. Red flags and red banners were plentiful, the Bolshevik banners reading “Down with the Ten Capitalistic Ministers,” “Down with the War,” “Down with the Duma,” “All the Power to the Soviets,” and presenting a very belligerent appearance.

With me that day was another woman writer, Miss Beatty of the San Francisco Bulletin, and as we walked along we agreed that almost anything could happen, and that we ought not to allow ourselves to get into a crowd. For once the journalistic passion for seeing the whole thing must give place to a decent regard for safety. We had just agreed that if shooting began we would duck into the nearest court or doorway, when something did happen—something so sudden that its very character could not be defined. If it was a shot, as some claimed, we did not hear it. All we heard was a noise something like a sudden wind. That great crowd marching along the broad Nevski simply exploded. There is no other word to express the panic that turned it without any warning into a fleeing, fighting, struggling, terror-stricken mob. The people rushed in every direction, knocking down everything in their track. Miss Beatty went down like a log, but she was up again in a flash, and we flung ourselves against a high iron railing guarding a shop window. Directly beside us lay a soldier who had had his head cut open by the glass sign against which he was thrown. Many others were injured.

Typical crowd on the Nevski Prospect during the Bolshevik or Maximalist risings.

Fortunately the panic was shortlived. It lasted hardly five minutes, as a matter of fact. All around the cry rose that nothing was the matter, that the Cossacks were not coming. The Cossacks, once the terror of the Russian people, in this upheaval have become the strongest supporters of the government. Nothing could better demonstrate the anti-government intention of the Bolsheviki than their present fear and hatred of the Cossacks. So the “Tavarishi” took up their battered banners and resumed their march. No one ever found out what started the panic. Some said that a shot was fired from a window on one of the banners. Others said that the shot was merely a tire blowing out. Some were certain that they heard a cry of “Cossacks,” and some cynics suggested that the pick-pockets, a numerous and enterprising class just now, started the panic in the interests of business. This was the only disturbance I witnessed. The newspapers reported two more in the course of the day. A young girl watching the procession from the sidewalk suddenly decided to commit suicide, and the shot she sent through her heart precipitated another panic. Still a third one occurred when two men got into a fight and one of them drew a knife.

The instant flight of the crowds and especially of the soldiers must have given Kerensky hope that the giant could be got back into the bottle, especially since on that very day, June 18, Russian style, the army on one of the fronts advanced and fought a victorious engagement. The town went mad with joy over that victory, showing, I think, that the heart of the Russian people is still intensely loyal to the allies, and deadly sick of the fantastic program of the extreme socialists. Crowds surged up and down the street bearing banners, flags, pictures of Kerensky. They thronged before the Marie Palace, where members of the government, officers, soldiers, sailors made long and rapturous speeches, full of patriotism. They sang, they shouted, all day and nearly all night. When they were not shouting “Long live Kerensky!” they were saying “This is the last of the Lenineites.” But it wasn’t. The Bolsheviki simply retired to their dancer’s palace, their Viborg retreats and their Kronstadt stronghold, and made another plan.

On Monday night, July 2, or in our calendar July 15, broke out what is known as the July revolution, the last bloody demonstration of the Bolsheviki. I had been absent from town for two weeks and returned to Petrograd early in the morning after the demonstration began. I stepped out of the Nicholai station and looked around for a droshky. Not one was in sight. No street cars were running. The town looked deserted. Silence reigned, a queer, sinister kind of a silence. “What in the world has happened?” I asked myself. A droshky appeared and I hailed it. When the izvostchik mentioned his price for driving me to my hotel I gasped, but I was two miles from home and there were no trams. So I accepted and we made the journey. Few people were abroad, and when I reached the hotel I found the entrance blocked with soldiers. The man behind the desk looked aghast to see me walk in, and he hastened to tell me that the Bolsheviki were making trouble again and all citizens had been requested to stay indoors until it was over.

I stayed indoors long enough to bathe and change, and then, as everything seemed quiet, I went out. Confidence was returning and the streets looked almost normal again. I walked down the Morskaia, finding the main telephone exchange so closely guarded that no one was even allowed to walk on the sidewalk below it. That telephone exchange had been fiercely attacked during the February revolution, and it was one of the most hotly disputed strategic positions in the capital. Later I am going to tell something of the part played in the revolution by the loyal telephone girls of Petrograd. A big armored car was plainly to be seen in the courtyard of the building, and many soldiers were there alert and ready. I stopped in at the big bookshop where English newspapers (a month old) were to be purchased, and bought one. The Journal de Petrograd, the French morning paper, I found had not been issued that day. Then I strolled down the Nevski. I had not gone far when I heard rifle shooting and then the sound, not to be mistaken, of machine gun fire. People turned in their tracks and bolted for the side streets. I bolted too, and made a record dash for the Hotel d’Europe. The firing went on for about an hour, and when I ventured out again it was to see huge gray motor trucks laden with armed men, rushing up and down the streets, guns bristling from all sides and machine guns fore and aft.

What had happened was this. The “Red Guard,” an armed band of workmen allied with the Bolsheviki, together with all the extremists who could be rallied by Lenine, and these included some very young boys, had been given arms and told to “go out in the streets.” This is a phrase that usually means go out and kill everything in sight. In this case the men were assured that the Kronstadt regiments would join them, that cruisers would come up the river and the whole government would be delivered into the hands of the Bolsheviki. The Kronstadt men did come in sufficient numbers to surround and hold for two days the Tauride Palace, where the Duma meets and the provisional government had its headquarters. The only reason why the bloodshed was not greater was that the soldiers in the various garrisons around the city refused to come out and fight. The sane members of the Soviet had begged them to remain in their casernes, and they obeyed. All day Tuesday and Wednesday the armed motor cars of the Bolsheviki dashed from barrack to barrack daring the soldiers to come out, and whenever they found a group of soldiers to fire on, they fired. Most of these loyal soldiers are Cossacks, and they are hated by the Bolsheviki.

Tuesday night there was some real fighting, for the Cossacks went to the Tauride Palace and freed the besieged ministers at the cost of the lives of a dozen or more men. Then the Cossacks started out to capture the Bolshevik armored cars. When they first went out it was with rifles only, which are mere toy pistols against machine guns. After one little skirmish I counted seventeen dead Cossack horses, and there were more farther down the street. As soon as the Cossacks were given proper arms they captured the armored trucks without much trouble. The Bolsheviki threw away their guns and fled like rabbits for their holes. Nevertheless a condition of warfare was maintained for the better part of a week, and the final burst of Bolshevik activity gave Petrograd, already sick of bloodshed, one more night of terror. That night I shall not soon forget.

The day had been quiet and we thought the trouble was over. I went to bed at half-past ten and was in my first sleep when a fusilade broke out, as it seemed, almost under my window. I sat up in bed, and within a few minutes, the machine guns had begun their infernal noise, like rattlesnakes in the prairie grass. I flung on a dressing gown and ran down the hall to a friend’s room. She dressed quickly and we went down stairs to the room of Mrs. Emmeline Pankhurst, the English suffragette, which gave a better view of the square than our own. There until nearly morning we sat without any lights, of course, listening to repeated bursts of firing, and the wicked put-put-put-put of the machine guns, watching from behind window draperies, the brilliant headlights of armored motors rushing into action, hearing the quick feet of men and horses hastening from their barracks. We did not go out. All a correspondent can do in the midst of a fight is to lie down on the ground and make himself as flat as possible, unless he can get into a shop where he hides under a table or a bench. That never seemed worth while to me, and I have no tales to tell of prowess under fire.

I listened to that night battle from the safety of the hotel, going the next day to see the damage done by the guns. A contingent of mutinous soldiers and sailors from Kronstadt, which had been expected for several days by the Lenineites, had come up late, still spoiling for a fight; had planted guns on the street in front of the Bourse and at the head of the Palace Bridge across the Neva, and simply mowed down as many people as were abroad at the hour. Nobody knows, except the authorities, how many were killed, but when we awoke the next day we discovered that, for a time at least, the power of the Bolsheviki had been broken. The next day the mutinous regiments were disbanded in disgrace. Petrograd was put under martial law, the streets were guarded with armored cars, thousands of Cossacks were brought in to police the place, and orders for the arrest of Lenine and his lieutenants were issued. But it was openly boasted by the Bolsheviki that the government was afraid to touch Lenine, and certain it is that he escaped into Sweden, and possibly from there into Germany.

I should not like to believe that the government actually connived at his escape, since there was always the menace of his return, and the absolute certainty that he would remain an outsider directing force in the Bolshevik campaign. It is more probable that in the confusion of those days of fighting he was smuggled down the Neva in a small yacht or motor boat to the fortress of Kronstadt, and from there was conveyed across the mine strewn Baltic into Sweden. Rumor had it that he had been seen well on his way to Germany, but it is more likely that his employers kept him nearer the scene of his activities. He was guilty of more successful intrigue, more murder and violent death than most of the Kaiser’s faithful, and deserves an extra size iron cross, if there is such a thing. In spite of all that he has done he has thousands of adherents still in Russia, people who believe that he is “sincere but misguided,” to use an overworked phrase. The rest of the fighting mob were driven from their palace, which they had previously looted and robbed of about twenty thousand dollars’ worth of costly furniture, china, silver and art objects. They were hunted out of their rifle factory, and finally surrendered to the government after they had captured, but failed to hold the fortress of Peter and Paul. They surrendered but were they arrested and punished? Not a bit of it. They were allowed to go scot free, only being required to give up their arms. The government existed only at the will of the mob, and the mob would not tolerate the arrest of “Tavarishi.”