CHAPTER XIII.

SECOND EXPEDITION.

Start of mission—Arrival at Mandalay—The Burmese pooay—Posturing girl—Reception by the meng-gyees—Audience by the king—Departure of mission—Progress up the river—Reception at Bhamô—British Residency—Mr. Margary—Account of his journey—The Woon of Bhamô—Entertains Margary—Chinese puppets—Selection of route—Sawady route—Bullock carriage—Woon of Shuaygoo—Chinese surmises—Letters to Chinese officials—Burmese worship-day.

In November 1874, Colonel Browne and myself arrived at Calcutta, having left England on receipt of telegraphic instructions in the preceding month. A short time was devoted to the purchase and preparation of the various articles intended as presents; while the necessary equipment of scientific instruments was completed under the personal supervision of Colonel Gastrell, of the Surveyor-General’s office, and nothing was spared by this well-known officer to make the fullest provision for all scientific purposes. Fifteen picked men were selected from a Calcutta regiment of Sikhs to form the guard, and all being thus ready, we proceeded to Rangoon, and thence, in the Ashley Eden steamer, began our journey up the Irawady on December 12th.

At Prome we picked up a Chinese named Li-kan-shin, who proved to be a nephew of Li-sieh-tai. He had been driven from his abode at Hawshuenshan by the Panthays, and had lived at Prome, where he bore the Burmese name of Moung Yoh. He now wished to return to Yunnan to visit his mother; as he spoke Burmese fluently, in addition to writing and speaking Chinese, he was taken into the service of the mission as an interpreter. At first he hesitated, fearing to be punished for bringing foreigners into Yunnan, but a sight of the imperial passport removed all his scruples.

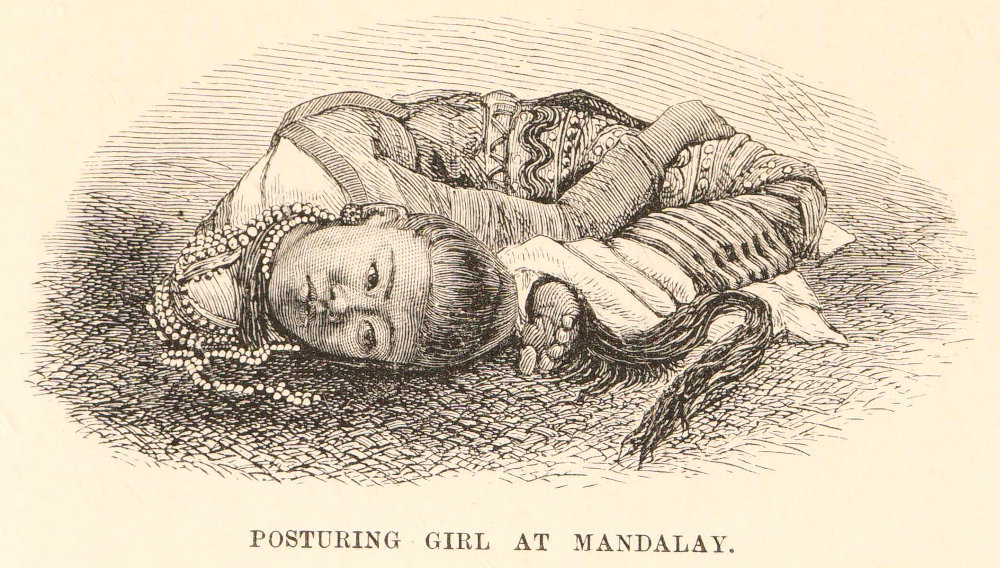

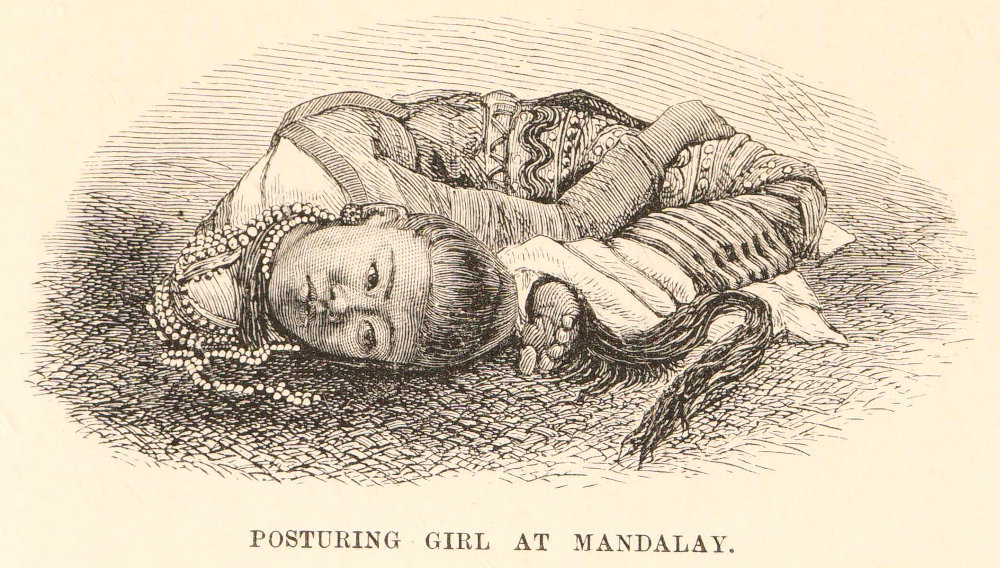

We arrived at Mandalay in the evening of December 23rd, 1874, and were received on landing by officials sent from the palace with royal elephants to carry us up to the Residency. Very different was the reception accorded to the members of this mission from the apparent neglect which had seemed to ignore our existence when on the expedition of 1868. All the marks of honour that are usually conferred on distinguished visitors were duly paid. Silver dishes loaded with dainties were sent from the palace, and we were declared to be the king’s guests, not only at the capital, but until we should have passed his frontiers, and have been safely handed over to the Chinese. For our delectation, also, the royal corps dramatique appeared to perform a pooay, or play, the most favourite amusement of the Burmese, even to the very youngest, who will sit for hours, and night after night, listening to the adventures of the royal heroes and heroines, and enjoying the jokes which are freely interspersed. The performance takes place under an open pavilion of bamboos erected for the occasion. There is no stage, but a circular space covered with mats is reserved for the performers, and the audience squat around the edge of the matted portion. The only indication of scenery is a tree set up in the centre to do duty for the forest, in which the scene of all Burmese dramas is laid. By this tree a huge faggot is placed and a large vessel of oil, and the blazing flame, fed from time to time with oil poured over it, illuminates the performance with a lurid light, which gives a fantastic appearance to the figures. A portion of the circle is reserved for the orchestra, the leader taking his place inside a hollow cylinder hung round with drums and cymbals, while the lesser musicians group themselves around the noisy centre. No permanent theatre exists even in the capital, nor are the performers paid by the audience. It is the custom for those who desire on any particular occasion to “give a pooay” to engage one of the various troupes of players, for whom a pavilion is extemporised opposite the house, while the public form regular rows around, and enjoy the gratuitous spectacle. Such an enclosure was set up in the Residency compound. The first intimation of the coming pooay was the early arrival of the orchestra some hours before the performance was to commence, making their presence known by a noisy rehearsal of the music of the play, which soon drew together an expectant crowd. As in pooays generally, the actors and actresses then by degrees dropped in, each accompanied by a friend or servant to assist in the toilettes, which were made in public; the men and women taking their places on opposite sides of the orchestra. The actors arrayed themselves in robes stiff with tinsel, over which they placed an apron of curious work and cumbrous form, and crowned their heads with a species of tiara shaped like a pagoda. Each actress brought with her a small box containing cosmetics, flowers for adorning her hair, and a little mirror. Seating herself on a mat, she substituted for her ordinary jacket a bespangled gauze coat over her richly woven silken tamein, or skirt, which was tucked so tightly round her limbs that it gave her a shuffling gait. The decorating of her hair with sweet-smelling flowers, the powdering of her face, and the painting of her eyebrows, constituted however the chef-d’œuvre of her toilette, requiring constant appeals to the mirror to ensure its success. She then as a finishing stroke threw around her neck numerous strings of imitation pearl beads, which reached down to nearly the knee, and in each lobe of her ears inserted a solid cylinder either of gold, jade, or amber, called a nodoung. She then smoked a cheroot while unconcernedly awaiting her call. This occupation, indeed, was never pretermitted during the performance, except while the actor’s lips were occupied in declamation or song. The royal prima donna, whose professional reputation is very high, and who sang sweetly, would at the end of a passionate outburst coolly relight her cheroot at the blazing faggot by the tree, and smoke it till her next speech or song. Besides the dramatic performers, the royal tumblers and jugglers appeared every afternoon, and executed surprising feats, which were witnessed by an enthusiastic crowd. The agility of the tumblers was remarkable. One man would, as it were, fly rather than spring over a row of nine boys arranged as if for leap-frog. He also leapt through a square formed by keen-edged knives held by two men, and disposed with the edges at right angles to his progress, and giving barely space for the passage of his body. One remarkable exhibition was that of a girl of sixteen, who possessed most singular elasticity of body. She laid herself on the ground, and, without apparent effort or distress, bent her body backwards till her toes rested on her head, as shown in the illustration taken from a photograph. She also possessed the power of moving the muscles of one side of her face and body, while those of the other side remained in a perfect state of repose. The feats of the jugglers were even more puzzling than those of the Indian performers, and seemed to be very popular with the crowd.

POSTURING GIRL AT MANDALAY.

The day after our arrival, the foreign minister, or kengwoon meng-gyee, paid us a visit, and invited us to a breakfast, which was served with great profusion, and was almost English in its style. At a separate table tea was prepared of two sorts; one the ordinary infusion of tea leaves, the other from hard black cakes stamped with Chinese letters, and exactly resembling tablets of Indian ink. These are prepared by the Shans from the Chinese leaf tea, and produce a liquor as pale as sherry, but of excellent flavour. The visit and breakfast of the foreign minister was followed in due succession by similar civilities on the part of the other meng-gyees; and a day was appointed for our presentation to the king, an honour which had been vouchsafed to the mission of 1868 neither on its outward nor homeward journey. Accompanied by the British Resident, Captain Strover, we proceeded on royal elephants, sent for our use, to the palace enclosure, where we found the meng-gyees seated on carpets in a small hlot, or open hall, outside the palace gate. Having doffed our shoes, we seated ourselves on the carpets with feet carefully hidden, according to court etiquette, and conversed with the ministers, while attendants served tea, fruits, and cakes. At last we were informed that the king was ready to receive us; so, having resumed our boots, we proceeded through a small postern in the inner palace stockade into the large open space, on the far side of which rose the lofty temple-like structure with its nine roofs, topped by the golden htee which marks the centre of the capital and state of Burma. Boots were again removed, and we ascended the short flight of steps into a spacious open hall with rows of gilded pillars, and filled with a numerous guard, all prostrated on their knees before the august presence of the meng-gyees who escorted us. Two more halls were successively passed through, and then through a side passage the audience hall was reached. This was a large apartment painted white, with a gilded railing cutting off two-thirds of its area. In the wall opposite to the railing were a pair of gilded folding-doors, and on the right and left a row of pillars. From amidst the ranks of the body-guard, all dressed in spotless white, and squatted on the ground, we entered within the railing, and imitated in our own way the uncomfortable position prescribed by etiquette, carefully turning our feet to the rear. Behind either side of us, were the ministers of state duly crouching. Before the folding-doors, and a few yards removed from us, was spread a gorgeous velvet carpet of red and gold pattern, on which stood a golden couch richly bejewelled. A square pillow, an opera-glass, and two golden boxes were laid ready for the absent occupant, and by the head of the couch stood a betel box in the form of a golden henza, or sacred goose, inlaid with jewels.

Presently the folding-doors were thrown open, disclosing a long vista of golden portals, through which we saw his Majesty of Burma advancing, accompanied by a little boy five or six years old. The Burmese ministers, courtiers, and body-guard instantly bowed their faces to the ground, and remained prone with hands held up in the attitude of supplication. The Europeans bowed after their fashion, and the king, a man of about sixty years, with a refined, intellectual face, quick eye, and pleasing but dignified manners, reclined on the couch and saluted us graciously. He then entered into a complimentary conversation, looking at us through his opera-glass, though not twenty yards distant. He expressed himself in the most friendly manner, and offered one of his steamers to convey the party to Bhamô, which was politely declined on the ground of all arrangements having been already made. All his questions were duly repeated by one of the officials crouching at our side, who rendered into courtly phraseology the somewhat laconic replies of Colonel Browne. After the interview had lasted about fifteen minutes, the king suddenly closed the conversation, the folding-doors flew open, and he disappeared. The Burmese raised their heads, the Englishmen stretched their legs, fruits and cakes were served on silver salvers and cold water in golden cups, while the meng-gyees themselves helped us and pressed us to eat.

Thence we were conducted to view the so-called white elephant in his small but richly adorned dwelling, which, with the concomitants of golden umbrellas and attendants, he does not deserve by his rarity, as he is not whiter, except about the head, than many elephants I have seen in India.

For the rest of the palace and the surrounding city, the short description already given will still serve. The suburbs manifested a decided increase in the number of buildings and population, and the inhabitants seemed more busy and prosperous than ever, as a proof of which we remarked a new bazaar, built two years ago, twelve hundred feet long and five hundred broad. The beauty of the environs, as viewed from the angle towers of the city wall, seemed as striking as when first beheld, and was enhanced by the lake-like waters of the broad moat which now surrounds the walls of the city. Besides this additional defence, the king is engaged in the construction of a fort on the left bank of the river between Ava and Amarapoora. When approaching the capital, we had noticed the works, distant at this season more than a mile from the channel, though in the rainy season the river must reach almost to the walls. Immediately opposite, on the right bank, rise the chimneys of an iron foundry erected to work the iron obtained from the neighbouring Tsagain hills. Like other Burmese works, both are still unfinished, and are likely never to reach completion.

The steamer Mandalay arrived on January 2nd, bringing the numerous and cumbrous boxes of presents, the Australian and Arab horses, and the kangaroo dogs, all under the charge of the Sikh guard and Mr. Fforde, superintendent of police, who was to bring the guard back from the frontiers of China. A list of the fire-arms on board had been forwarded to the royal officials, and the Burmese customs officers had examined those brought at the frontier station of Menhla to see that they tallied with the list. On the following day we embarked, accompanied by Captain Strover and his medical attendant, Dr. Cullimore, who, with a tsare-daw-gyee deputed by the king to look after our wants, were to accompany us as far as Bhamô.

The cordial reception experienced at the capital, and the readiness shown by all the officials to “comfort and assist” the mission, seemed to prove from the first that the king of Burma was sincere in his promise to secure us a safe passage through his dominions. Sinister rumours of his real dislike to the mission were, it may be said, of course, not wanting, some of which reached our ears in the capital itself, and others at a later period. However, we felt more inclined to regard actions than mere words, and there has been no reason subsequently to doubt the king of Burma respecting the promises he had made. A royal steamer, laden with cargo and passengers, left the capital for Bhamô before we got our steamer and its flat under weigh. The latter was a large barge, somewhat resembling a Thames shallop, the hull loaded with three hundred tons of salt, and the main deck, over which the upper deck, or rather story, was raised on iron uprights, crowded with steerage passengers. Our party occupied the cabins in the fore part of the flat, the forecastle of which served us as an open-air saloon. The navigation of the Irawady in the dry season is somewhat uncertain, and the voyage proved unusually long. We had scarcely proceeded a few miles when it was discovered that the stores for the guard had been unloaded at Mandalay, and it was necessary for the steamer to cast off the flat, and return for the missing provender. The next morning, soon after starting, some native boats, laden with firewood, coming down the river, were swept by an eddy under the paddle-wheels. The steamer had been stopped, but the crews, being short-handed, were unable to pull their boats clear; they managed, however, to save their lives, but boats and cargo were totally lost. The next incident was the grounding of our too deeply laden flat on a sandbank, where we were obliged to remain for four days, until the steamer returned to Mandalay for a second flat, into which part of the cargo was transhipped. Thus by the end of the first week, we had only made twenty-five miles out of the two hundred and fifty to Bhamô.

From this point, no further delays were experienced, save those due to the usual morning fogs; and our upward voyage was, in all other respects, agreeable. We were received with every demonstration of respect by the officials of all the towns en route. On approaching the places of most importance, we were met by war-boats sent to escort us for a mile or more to the landing, where the local militia was arrayed as a guard of honour. Reception halls had been erected, and the young women were assembled singing and dancing, or rather posturing, as the performers do not stir from one spot, but sway the body and arms in measured and not ungraceful movements. Sometimes, when unable to stop, we saw the dance proceeding on the river bank. At Myadoung, the “army” drawn up in our honour consisted of three hundred men, ranged along the bank, who executed a serpentine manœuvre, as they marched to receive us at the landing-place, apparently to make their array seem more imposing; they wore no uniforms, and, besides dahs and spears, carried very old and well-worn flint muskets. At this place a handsome shed had been erected, where no less than sixty-four fair performers were assembled, and in the evening we patronised, by request, the performance of a regular pooay. All these entertainments had been commissioned by royal order, which the local officials obeyed to the best of their ability. Thus the Shuaygoo Woon came on board, and most earnestly invited us to halt for an hour, and honour his pooay by our presence, a request which, if we had known his real sentiments towards English visitors, would scarcely have been complied with. Above the second defile, we met the steamer which had preceded us coming down on her return trip, with a large flat laden with cargo and passengers.

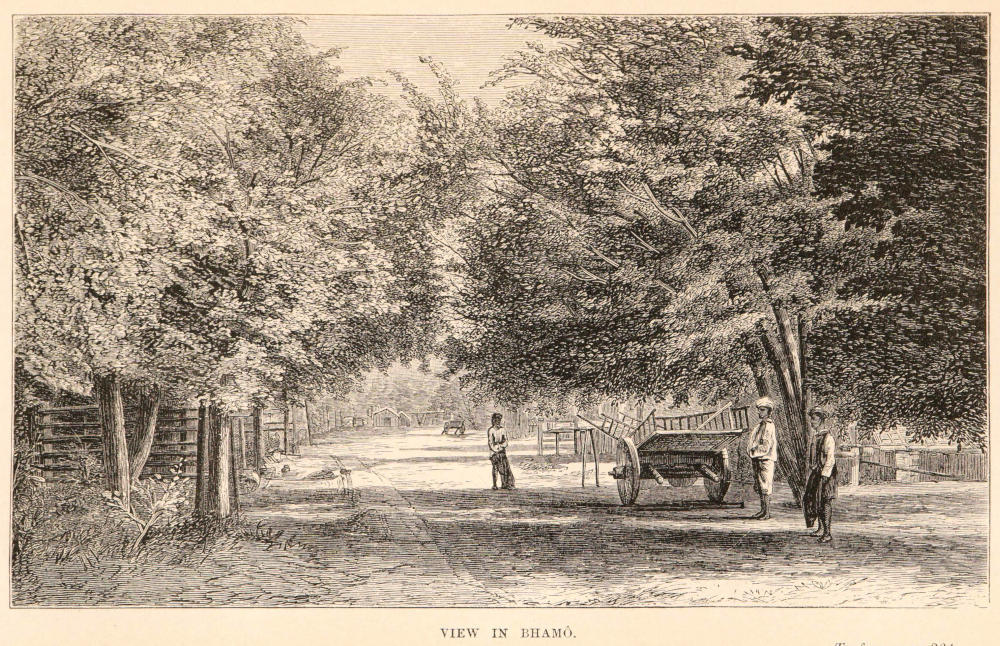

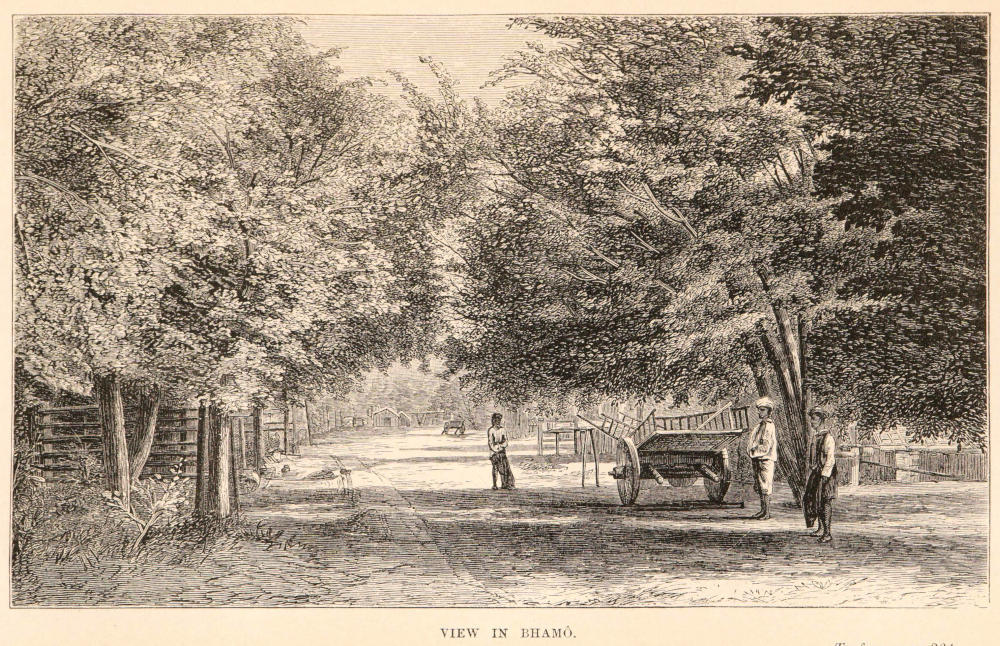

We did not complete our journey till January 15th, having spent twelve days on the voyage, the last twelve miles of which, owing to the difficulty of the channel, took ten hours to accomplish. As the steamer neared the high river bank, the southern end of Bhamô, twelve large war-boats, each manned by thirty men, and one of which contained Captain Cooke, the British Resident, the Woon, and the other Burmese officials, paddled out to meet us, with much beating of gongs, and, passing in order, turned and followed in a long procession. The high bank was crowded with the townspeople, Shan-Burmese and Chinese, with an intermixture of Chinese Shans and Kakhyens. As soon as the steamer and flats were moored, the Resident and the Woon, with his tsitkays, came on board, and welcomed us to Bhamô. The Burmese had prepared a house in the town for our accommodation, but the Resident pressed us to take up our quarters in the Residency, whither we according proceeded. This is a fine building of teak, which has been erected at a cost of £1100, though a similar one at Rangoon would have cost at least £2000. It occupies a commanding position on the site of an old Chinese fort near the river bank, about a mile north of the town. This old fort, at my first visit, was completely hidden in jungle; the moat is still wonderfully perfect, and encloses a large area, of which the residency compound, about two acres in extent, forms but a small portion. This is surrounded by a fence or wooden framework, covered with mats. Outside the gate a zayat has been erected, which at this period was occupied by about fifty Kakhyens of the Mattin clan, whose chief had been summoned to Bhamô in reference to the possible claims of the central or embassy route. Living within the compound were a number of Shan families from the Sanda valley, who were waiting for the arrival of the Mandalay to carry them down the river, on a pilgrimage to the shrines of Rangoon. It was impossible to avoid regretting that the Residency has been built so far from the town, and in a situation so exposed to any sudden attack from Kakhyen or any other marauders. The jungle grows to the very edge of the moat, affording complete cover for assailants, while the interstices of the fence afford abundant opportunities for intruding guns or spears. One would think that the selection of a site within the town, and near the Woon’s house, would have seemed to argue more confidence in the Burmese authorities, with whom the Resident should be in constant and friendly intercourse, in order to effectually look after the interests confided to him, without setting up an imperium in imperio over the Kakhyens of the hills. Recent events have shown the insecurity of the present position, which, in the case of any serious attack, could not be defended by the sepoys of the Residency guard, who, at the time of our visit, could only muster eight effective men.

At the Residency we were welcomed by Mrs. Cooke, who shares with her husband the risks and banishment of life in this far-off place, giving a striking proof of the pluck and devotion to their lords which characterises our countrywomen. Here, too, we made the acquaintance with our future travelling companion, Mr. Ney Elias, and received the information that Mr. Margary had arrived safely at Manwyne, and might be daily expected to make his appearance at Bhamô.

The day after our arrival, we decided that Colonel Browne, Mr. Fforde, and myself, should reside in the town of Bhamô, for the greater convenience of communication with the Burmese, and, as far as I was concerned, with my staff of collectors. The Woon at once placed at my disposal a small bamboo structure, built on the site of the house tenanted by us in 1868. Opposite to it was the house, newly built, in readiness for the present mission, in which Colonel Browne and Mr. Fforde took up their quarters. The Woon was evidently much gratified by this proceeding on the part of the officers of the mission, as showing a friendly appreciation of his good offices. A temporary pavilion was speedily erected over the street between the two houses, and on our return from the Residency in the evening, a pooay was in full play before an admiring audience. As soon as we had taken our seats in the front of the verandah, trays of sweetmeats were set before us, and we sat and viewed the performance till nearly midnight, as the jovial laughter of the Burmese at the very broad jokes of the artists was not conducive to sleep.

VIEW IN BHAMÔ.

On the 17th, we were agreeably surprised by the arrival of Mr. Margary, looking none the worse for his long overland journey from Hankow, which he had left on the 4th of last September. But for a delay at Loshan of six days, while waiting for new instructions, he would have accomplished this tremendous journey in just four months. Starting from Hankow, and passing the Tung-ting lake, on the Yang-tse, he had ascended the Yuen river through Hoonan, and travelled by land through Kweichow and Yunnan.

The only real difficulty he experienced was at a town called Chen-yuen, in Kweichow, where the boat journey ended on October 27th. Here the populace endeavoured to prevent the removal of his luggage from the boat, and it was only by means of an appeal to the mandarin, who at first was uncivil but speedily yielded to the power of the passports, and the interference of an armed guard sent by that official, that he was enabled to proceed. It was necessary for him to sleep at the Yamen, and leave the town in the early morning. When the mob learned his departure, they wreaked their vengeance on the boatmen, and destroyed their boat. On his land journey the people were everywhere civil, though intensely curious, and the mandarins polite. He described the scenery in Kweichow as splendid, but the roads rough and ragged, carried almost always at a high level along pine-clad hills overlooking valleys far beneath. The province appeared to have been sadly devastated—the cities reduced to mere villages, and the villages to collections of straw huts; everywhere ruins of good, substantial stone houses abounded to show the former prosperity of the region before the Miaou-tse came down from the hills and butchered the whole population. Although twenty years have elapsed since this incursion, the cities still remain like cities of the dead—their extensive walls surrounding acres of ruins, with a few of the wild hillmen dwelling in them.

His reception by the governor of the province at Kwei-yang-fu was very cordial; and the latter promised to compensate the boatmen for their loss in the destruction of their boat by the Chen-yuen mob. From this city twenty days of steady travelling in a chair, twenty miles a day, over fine mountains and through valleys almost deserted, brought him to Yunnan-fu on November 27th. He met with civility everywhere; but the acting governor-general of Yunnan, who was then locum tenens of the absent viceroy, proved himself a most friendly and indeed an unexpected ally. Not content with loading the Englishman with honours and courtesies, he sent two mandarins to escort him the rest of the way, and despatched an avant-courrier bearing a mandate to all the local authorities, which secured marked respect for the traveller, and also sent a quick courier with orders to the mandarins on the frontier to take care of the expedition in case he should not have met us before our entrance into China. From Yunnan to Tali a dreadfully rough road or track of deep ruts and jagged stones led over high mountains and into deep valleys. The ascents were so steep as to require a team of eight or ten coolies harnessed with ropes to drag the chair up the dangerous incline, often skirting the edge of a precipice; and in the narrow and dangerous path strings of mules and ponies laden with salt were often met with, to the great risk of the traveller.

The state of the country is best described in his own words:—“It is melancholy to see these fine valleys given up to rank grass, and the ruined villages and plainly distinguishable fields lying in silent attestation of former prosperity. Every day I come to what was a busy city, but now only containing a few new houses inside walls which surround a wide space of ruins. But the people are returning gradually, and the blue smoke can be seen curling up here and there against the background of pine-clad hills. It must take some few years to re-people the country, rich as it is.”

The last four days’ travelling before reaching the plain of Tali passed through a mountainous district devoid of cities. The authorities of Tali were at first averse to his entering the city, pleading their fear of the turbulent and dangerous populace, against whom he had been already warned by the viceroy; but by an adroit appeal to the laws of etiquette, which constrained him to pay his respects to the high authorities, he got over the difficulty. The much dreaded city populace treated him not only with courtesy but with profound respect, calling him Ta-jen, or Excellency. The several officials received him well, and the Tartar general, an enormously large man, who had been foremost in the storming of the city, placed him in the seat of honour by himself, asked innumerable questions about England and Burma, and promised to invite the mission to stay a few days at Tali-fu.

Yung-chang was reached on December 27th, after passing through “glorious scenery,” by a road leading over high mountain regions, but with nothing so bad as “the horrid passes” previously encountered. A daring robbery had been just committed on the highway, and a halt was necessitated for the soldiers to scour the hills for fear of lurking dacoits. The people were gradually returning to the villages, and burning the jungle grass, which had overgrown the long abandoned fields. The mandarins at Yung-chang were inclined to be obstructive; but those at Teng-yue-chow, or Momien, which was reached in four days from the former city, were “delightfully civil.” Here he received the despatches informing him of the plans of the mission, and in accordance with them he set out for Manwyne, arriving there after a journey of five stages through the Shan country, which he described as a lovely valley, and the people as sociable and amiable. At Manwyne he found the Burmese guard of forty men, who had been sent forward from Tsitkaw to escort him through the Kakhyen hills. Here also he met with the redoubtable Li-sieh-tai, “now a Chinese general,” who was negotiating a tariff of imposts on trade with the Kakhyen chiefs and Shan headmen. Li received his first English visitor with the greatest honour, kotouing to him before all the assembled chiefs and notables. The Burmese officers requested a delay to recruit their men, after the march over the hills, and Margary, who was anxious to press on, endeavoured vainly to induce Li to give him a guard, under whose protection he could advance, leaving his followers and baggage to follow with the Burmese. He recorded his opinion that there were intrigues going on in this district adverse to the advance of the mission, but notwithstanding he relied strongly on the express commands of the all-powerful governor of Yunnan in its favour.

His stay at Manwyne was marked by the most friendly intercourse with the tsawbwa and his family, whose guest he was. He walked through the town and shot over the banks of the river freely and unmolested; and, as he writes, “I come and go without meeting the slightest rudeness among this charming people, and they address me with the greatest respect.”

Under the escort of the Burmese guard he crossed the Kakhyen hills, bivouacking one night in a clearing, as we had done on the former journey, at Lakhon. He passed through eight or nine villages of the Kakhyens, the savage appearance of these hill people striking him forcibly after the civilised aspect of the Shans of the valleys, and they treated him to a specimen of their bold impudence. His servant Lin was menaced by one of these with a large stone, which he raised to strike him with, and another drew his dah and made a daring attempt to rob one of the men of his bag. After remaining a night at Tsitkaw, he and his party descended the Tapeng by boat, and reached the Residency early in the forenoon. It can easily be imagined with what feelings we congratulated the first Englishman who had succeeded in traversing “the trade route of the future,” as he called it, and with what pleasant anticipations we heard of the accounts of his arduous but successful journey, and the reception accorded all along the line of route, crowned by the politeness shown by the dreaded Li-sieh-tai. The astonishment and admiration of the Burmese was even greater. In their own minds they had never realised the existence of English officials in China, and now there appeared a veritable Englishman speaking Chinese fluently, and versed in the use of chopsticks and all other points of etiquette. This Petching meng, or Pekin mandarin, moreover, was attended, besides the rest of his retinue, by a most imposing literate, whose huge round spectacles gave him an aspect of wonderful wisdom, and commanded the greatest respect from his countrymen at Bhamô.

This worthy man, whose real name was Yu-tu-chien, and whose office was that of writer or Chinese secretary, was a Christian from the province of Hoopeh, one of the many sincere converts made by the Lazarist missionaries. His intelligence and anxiety for knowledge, with his amiable and faithful disposition, made him justly a favourite with all. From the Woon downwards, every inhabitant who could speak Chinese was anxious to interview and pay respects to the new-comers from Pekin, and devoutly believed that the writer was a lesser mandarin sent in attendance on the great man, and it must be confessed that Yu-tu evidently increased in self-respect as he realised the estimation in which he was held by the Chinese-speaking people, including the tsawbwa of Mattin and his followers.

The Woon, or governor of the town or district of Bhamô, was most zealous in carrying out the royal orders, and was personally most friendly. He was a short, elderly Burman, with prominent eyes and good face, whose chief occupation seemed to be incessantly muttering prayers, as he slid through his fingers the beads of the black amber rosary which he invariably carried. His principal wife and his children had been left in Mandalay as hostages for his good behaviour, according to the usual Burmese policy; but his establishment was presided over by a second or inferior wife, a stout elderly lady, whose acquaintance I was privileged to make. This was on the occasion of an entertainment given by him in honour of Margary, the day but one after his arrival. We sat with him on carpets in his verandah, while about forty of the prettiest and best dressed women of Bhamô, ranged in lines, postured and sang in the covered courtyard below. The various officials formed a background, and the crowd surrounded the performers. The infusion of Shan blood is evident in the superior good looks and physique of these daughters of the land. All were well dressed and adorned with silver and some with gold bracelets and other jewellery; the older and very much uglier women stood behind the last row of performers, and led the singing. We squatted Burmese fashion, and smoked, while tea and Huntley and Palmer’s biscuits were served with nuts and persimmons dried in sugar, followed by the customary betel and pan. Fortunately, etiquette did not oblige us to continue too long in the uncomfortable posture, which Burmese adopt by habit, and we could come and go as we liked during the two hours that the performance lasted. In the evening we visited the Chinese temple, in which a ceremony or function was proceeding on behalf of a Chinese townsman who had recently become insane. One part of the ceremonial consisted of a theatrical performance or puppet-show, viewed through a transparency, the actors being represented by small figures cut out of leather, with talc heads; they were moved by bamboos, one fixed at the back and another to one of the arms. The figures were placed close behind the transparent window, and a Chinaman in charge of each shouted the words of the part, while he manipulated the figure with great skill. We were permitted to go behind the scenes, and by a narrow wooden staircase ascended to a lobby leading into a large room, which was full of Chinese, smoking and drinking tea. Hundreds of the leather puppets were suspended round the room from lines, as if they had been clothes hung up to dry. This was at once the stage, green-room, and orchestra. The musicians were seated along the walls on benches; the instruments were a flageolet and a small violin, formed of a segment of bamboo, with a snake skin over the opening, and two strings stretched to the end of the bamboo handle. One man thumped two stones on a desk by way of drum; another played the cymbals, and others small gongs. Behind the transparent windows, at one end, stood a row of Chinese moving the puppets and shouting the dialogue. All were amateurs engaged in a work of charity, though how the patient was to be benefitted did not appear.

During this exchange of civilities, the preparations for as early an advance as was possible were not pretermitted. With regard to the route to be traversed by the expedition, the Woon had fully expected that the embassy or central road would be selected, and the Mattin tsawbwa, through whose territory it passes, had come to Bhamô to make arrangements for our transit. The Burmese preferred this route, as they had more influence over those Kakhyens, and declared that they could guarantee our safe passage more certainly by this route than any other. The line to be followed would correspond with that travelled over on our return journey in 1868. A Burmese embassy, carrying tribute to China, had recently gone by this road, but was reported to have been detained in the hills for more than a month, the mountaineers having barricaded the road, in order to effectually extort black mail. This embassy, or some of their members, had been heard of by Margary, as he was passing near Momien. The fact that the tribute-bearing Burmese embassies were accustomed to travel by this route did not recommend it as advisable for the passage of our expedition, and the Political Resident, with Mr. Elias, acting under orders, had, before our arrival, made arrangements for us to proceed by the Sawady route. From thence the road leads to Mansay, ten miles distant, a Shan village under Burmese and Kakhyen protection, which is the regular rendezvous for all Kakhyens coming down to Sawady or Kaungtoung to barter their goods for salt and ngapé. From Mansay, four marches through the country of the Lenna Kakhyens conduct to Kwotloon, in the Shan state of Muangmow, on the right bank of the Shuaylee. Thence the proposed route goes by way of Sehfan, a Chinese Shan state, dependent on the governor of the walled town of Muanglong, up the valley of the Shuaylee, and crosses the watershed to Momien. Such information as was possessed had been obtained by Moung Mo, the Kakhyen interpreter, who had been despatched by the Resident, in 1873, to Muangwan, and thence to Sehfan. He described the country between this and Muangmow as a cultivated plain, studded with villages, and the Shuaylee as a deep river a hundred yards wide. Sehfan is a small town of three hundred houses, surrounded by numerous large villages. Its chief had been brought up by the Chinese governor of Muanglong, and was a firm friend of the Chinese; he had recently married the eldest daughter of my old friend, the Hotha chief, with whom we had spent such pleasant days in 1868.

In 1873, great disturbances were caused by the aggressions of a Shan rebel from Namkhan, a Burmese Shan state on the left bank of the Shuaylee; and the Maran Kakhyens, who were at feud with the next clan of the Atsees, frequently attacked caravans and looted Sehfan villages. Beyond Sehfan lay the populous Chinese Shan states of Muangkwan, with two large towns of one thousand houses, and Muangkah on the Salween. The Chinese towns of Muanglong and Muanglem were both described as containing four thousand to five thousand houses, which is probably an exaggeration.

Agreements had been entered into with the Paloungto Kakhyen chief, who had undertaken to provide two hundred bullocks for carriage, mules not being procurable, and to escort the mission safely into the Muangmow district. The necessity of employing pack bullocks extended the time likely to be required for the journey to Momien to thirty or forty days; as, however, it was a principal object to explore this partially known route, which was universally admitted to present the fewest physical difficulties, the time so expended and the slow rate of travelling appeared likely to afford the scientific members of the mission more ample time for inquiry and observations. In this view of the case, the leader did not wholly concur, and though deciding to proceed to Muangmow, he contemplated striking off thence via Muangwan and Nantin.

It turned out to have been overlooked in the preliminary arrangements that Sawady is not in the Bhamô district, but under the jurisdiction of the Woon of Shuaygoo, to whom no orders had been sent from Mandalay. The Woon of Bhamô was rather nonplussed by our decision to adopt the Sawady route, but sent to request his colleague of Shuaygoo to come and advise on the subject. This, however, the official, who, as it afterwards appeared, is utterly hostile to Englishmen, altogether refused to do; but the Bhamô Woon decided to send his own troops under the command of a tsitkay, a veteran officer, to escort us as far as Mansay; but he evidently considered the Kakhyens beyond that point as refractory, though nominally in the Burmese territory. The Kakhyen pawmines declared their willingness to be answerable for our safety from Mansay if the Burmese would convoy us thus far, and then reviewed our two hundred packages, at the size of which they shook their heads. The boxes had all been carefully calculated to hold seventy-five pounds each, half a load for a mule, which carries fifty viss, equal to one hundred and fifty pounds, and had been constructed for package on the cross-trees used in mule carriage. Bullocks, however, cannot carry so much, and the goods are loaded on them in bamboo baskets, which, lined with the bamboo spathes, are almost watertight. It became necessary, therefore, to rearrange the cumbrous baggage, which was a work of some days.

Profiting by the experience of the former expedition, Colonel Browne resolved not to be encumbered with a cash-chest. All the coined money was exchanged for sycee, or lump, silver, at the rate of one hundred rupees for seventy tickals of the finest quality, or seventy-three tickals and a half of the more alloyed which passes among the Kakhyens, and these ingots were distributed among the private boxes of the party.

Our inquiries about the several routes brought out the fact that the Chinese fully believed us to be intent on making a railway, one man remarking that the Sawady route was much the longest, but, “of course, the best for the railway.”

It is hard to follow the workings of the Chinese mind, but it was plain that the objects of our expedition were as far from being perfectly understood by them as ever, and that they watched the movements of the mission with a secret feeling that the objects contemplated were somewhat beyond the peaceful pursuit of the interests of commerce and scientific inquiry.

During the delay consequent on the alteration of the packages, our friend the Woon got up pooays, or dances, for our amusement, and for three hours at a time relays of women from the different quarters of the town danced and sang.

Shan letters were sent to the tsawbwa of Muangmow, and Margary despatched Chinese letters to the governor of Momien and to Li-sieh-tai, who had sent Kakhyen messengers to Tsitkaw to carry them forward. It subsequently appeared that the letter had not reached Li, as he had left Nantin before the arrival of the messenger, and proceeded to Muangmow to await our coming.

The 21st was a day of heavy rain, which seriously interfered with packing arrangements; and as it was full moon, all amusement was interdicted by the observance of the Burmese worship-day, which was ushered in by the tolling of the Woon’s gong at seven, and at eight o’clock we found him presiding over a congregation which assembled in his house, the prayers being led by several priests. Our tai was quite free from the motley group of Burmese, Shan, and Kakhyen visitors who had daily thronged it. This strict observance of what may be called the sabbath was due to a recent revival of piety, stimulated by royal orders on the subject.