CHAPTER XV.

THE ADVANCE.

Residence at Tsitkaw—View from our house—The Namthabet—Junction of the rivers—Arrival of the Woon—Conference of tsawbwas—Hostages—Kakhyen women—Rifle practice—A night alarm—A curious talisman—We leave Tsitkaw—Camp at Tsihet—Burmese guard-houses—Lankon, Ponline—Camp on the Moonam—Hostile rumours—Camp on the Nampoung—Departure of Margary for Manwyne—Escape of hostages—Letter from Margary—We enter China—Camp on Shitee Meru—Burmese vigilance—Visit to Seray—Conference with Seray tsawbwa—Suspicious reception—Return to camp—Burmese barricades.

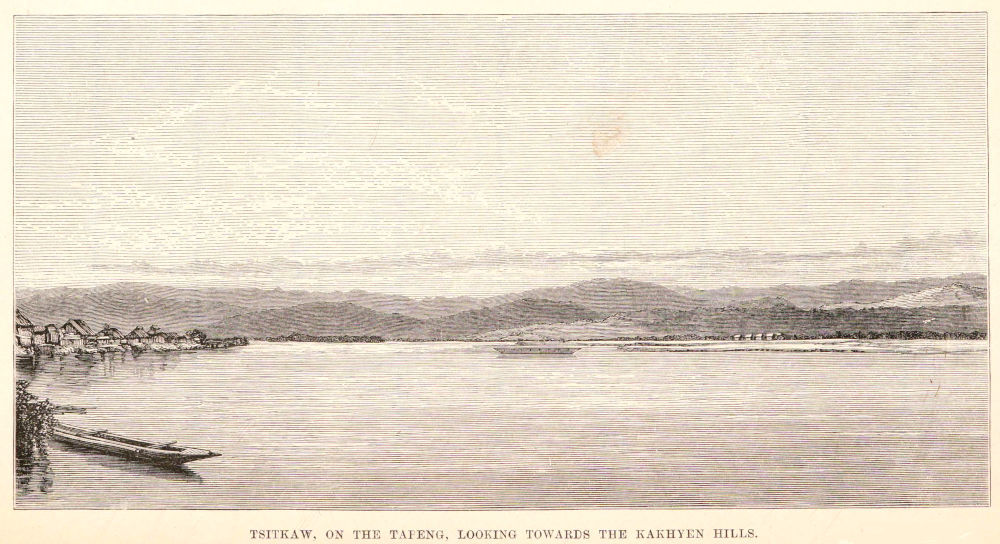

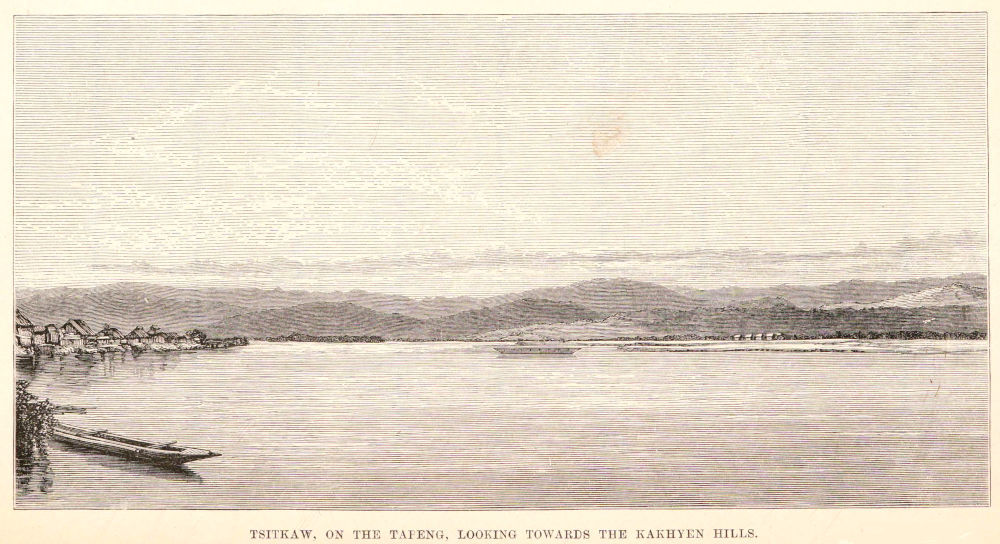

The village of Tsitkaw, which seemed little changed as to its dirty poverty since my recollections of 1868, consists of about eighty huts, built on piles, enclosed within a bamboo stockade, which was being repaired. The western half of the village is occupied by Chinese, and for the first time the Chinese women are seen, for there are none in Bhamô. At this time the Celestials were busy erecting a wooden temple outside the stockade. Their principal men came to our khyoung to greet Li-kan-shin, otherwise Moung Yoh, who was known to them, and had been supposed to be dead. In the Buddhist khyoung, two French missionaries, Father Lecomte and another, whom we had met at Bhamô, had taken up their abode. They professed to be engaged in opening communications between their mission in Burma and that in Yunnan, and had made interest to accompany our party. It now appeared that they proposed proceeding to Manwyne by themselves; but the Woon of Bhamô interfered, and refused to allow them to enter the Kakhyen hills on the north of the Tapeng. We were rather puzzled to understand their exact object or account for their sudden change of plans.

TSITKAW, ON THE TAPENG, LOOKING TOWARDS THE KAKHYEN HILLS.

We had to remain at Tsitkaw some days, until the Kakhyen chiefs assembled and the mules for carriage to Manwyne arrived. The air and water are better than at Bhamô, and our sojourn, with its excursions, was a pleasant time. Our residence consisted of two bamboo houses, as it were, placed side by side, the drainage of the two roofs in the centre being caught in a hollowed log of wood. A wooden ladder led up to the first apartment, beyond which the sleeping room was shut off by a kalagah, or curtain. To the rear a wide alluvial flat stretched away to the dense jungles swarming with tigers, and beyond which lay the Manloung lake and its adjoining swamps. From the front a charming view presented itself. Below a grassy bank ran the swift, smooth stream, one hundred and fifty yards broad, bordered on the other side by yellow sandbanks, fringed by a high screen of rich verdure marking the limit of the Tapeng in flood. Beyond this rose the wall of the luxuriant forest, backed by the lofty, well wooded Kakhyen mountains. Six miles distant, this wall appeared unbroken, for the gorge by which this river debouches is masked by a low line of hills, round which the Tapeng is deflected in a north-west direction, until it comes round above Tsitkaw, to flow towards the Irawady. There were manifold temptations for a sportsman or a naturalist; on the long alluvial flat, in the morning, flocks of parrots, Sarus crane, and Brahminy ducks, were seen feeding in numbers, and large snipe and glossy ibis abounded in the paddy fields. On the sandbanks bordering the river, flocks of wild geese were wont to settle, and afforded us some most literally wild goose chases. In the great trees, as Margary said, the gorgeous peacocks were as plentiful as magpies, and he was most anxious to secure some of their feathered spoils, to send to General Chiang at Momien, who wanted the plumage for his hat. We participated in most enjoyable excursions, and, to quote his words again, led a regular gipsy life. One was to Manloung lake, where our havildar shot a deer, to the delight of the Sikhs, who expressed unqualified admiration of the country, and a strong desire that we should annex it.

One day was devoted to a long walk to the Namthabet river, beyond the detached range of low hills. From the village of Tsitgna, we crossed in a dug-out to the opposite village of Kambanee, where we observed some Kakhyen women, who seemed almost too frightened to raise their eyes from the ground. The road, at first broad and good, led through a level tract, covered by forest of eng tree and high grass, of the same character as that which extends between Bhamô and the hills. As the land rose in long undulations, the character of the forest changed, a variety of timber succeeded the eng trees, and dense groves of bamboos filled the hollows. The slopes soon led up to a tolerably high ridge, covered with dense forest, except where patches had been cleared for the cultivation of maize. The summit commanded an extensive view of the Tapeng plain, and of the Manloung lake, which was seen to cover a large area. We descended by a steep path, winding through bamboo thickets and clearings. In traversing this richly wooded tract, which seemingly contained all the essentials of a sylvan paradise, we were impressed with the paucity of bird life; only a few parrots screeched their surprise at the intruders. On a high tree, three pigmy hawks were seen, one of which fell a victim to the exigences of science.

We presently came on the Namthabet, a clear, rapid stream, winding in a rocky channel down a narrow valley, beyond which rose the mass of the Kakhyen hills, clothed with dense forest. A Kakhyen woman was just about to cross from the opposite side, but fled at our appearance, and no persuasion on the part of our guide could induce her to return. We descended the valley, passing a fire, on which rice was cooking in a green bamboo, but the owner had hidden himself in the bush. We reached the Tapeng at a place where a sort of slide had been cut in the banks, down which the bamboos, when felled, are launched into the river, to be floated into the Irawady, where they are made into rafts, and sent down stream to the capital. A party of Kakhyens were seen busy at work cutting bamboos, and we passed their temporary huts in a clearing; and those of our party who were unacquainted with them seemed surprised at their peaceful and friendly demeanour. A scramble over the rocky left bank of the Tapeng brought us to the junction of the two rivers, and the day’s march of fifteen miles was more than repaid by the magnificent beauty of the gorge through which the Tapeng debouched from the main range. The towering masses and walls of rock, clothed to their summits with forest, at the base of which the river flowed deep and slow, the exquisite foliage, and the rich colour of brilliant flowers, made up an enchanting scene, very different from that which the same river presented when last I viewed it, under lowering clouds and in full flood, the height of which was now indicated by a faint brown line on the rocks, thirty feet above its present level. The Namthabet flowed out of a lesser gorge spanned by a ricketty bamboo bridge, which one of us tried to walk over, but was speedily reduced to fall on hands and knees and crawl across the vibrating structure. We made our way back by a forest path through tangled vegetation, over the ups and downs of the ridge, until the proper road was struck, by which Kambanee was reached near sundown.

An armed party, preceded by a sonorous gong, were descried making for Tsitkaw, and at Tsitgna we learned that our old friend the Woon had arrived in person from Bhamô to expedite the arrangements for our progress to Manwyne. A conference had been held some days previously with the tsawbwas of the northern hills; among whom were conspicuous our old friend or enemy, Sala, the Ponline chief, and the pawmine of Ponsee whom we had nicknamed “Death’s Head;” with them were others, whose names were unknown to us. It had been agreed that the hire to be paid per mule to Manwyne should be seven rupees eight annas, besides a fee, by way of tax or toll, of five rupees for each animal. The final arrangements had been postponed for five days, when a buffalo sacrifice was to be held, at which all the chiefs interested could be present. They had been convened at Manwyne not by mandarins but by merchants, who wished to remonstrate with them about the robberies of caravans, which constantly occurred on the Ponsee route. An instance of this was reported during our stay, by some Chinese, who came in and averred that they had been fired on by Kakhyens, near Ponsee, and had been compelled to pay two hundred rupees blackmail. The day following the Woon’s arrival, the Seray chief was alleged to have brought in a drove of mules. Colonel Browne, on the Woon’s invitation, attended a second conference, at which all the chiefs were present, and signed an agreement, drawn up in Burmese. It was stipulated that they should convey us safely to Manwyne, at which place the agreed upon presents should be distributed to them, and that the sons of the Ponline, Ponsee, and Seray tsawbwas should be detained as hostages for the fulfilment of the contract.

The son of the Seray chief was a young man whose demeanour and countenance gave a most unfavourable impression; in fact, he appeared to be a dissipated young ruffian, and decidedly unfriendly to the strangers. Sala’s son was a lad of fourteen, much superior to his father in appearance and manner; he was a frequent visitor to our khyoung, and also a patient, as he suffered, like many of his countrymen, from inflamed eyes, for the cure of which he seemed duly grateful. He was rather a favourite of the old Woon, who took him to Bhamô, and it is to be hoped that the better education and training will fit him to be a better chief than his avaricious and treacherous father.

Consequent on the arrival of the tsawbwas, was a large influx of their subjects, who flocked in in great numbers, both of men and women, bringing presents of fowls and vegetables, and bamboo flasks of sheroo. The members of our party who saw them in their native independence for the first time were greatly interested in the “little scowling women” and the half savage men. An unpublished letter, almost the last written by Margary, graphically depicts them:—“We let them ascend to our ratan floor, raised on stakes, and apart from the novelty, and indeed fun, of trying to buy their various curiosities, it is by no means a savoury infliction. The shocks of an electric machine produce a constant flow of merriment, and we roar with laughter at the grimaces and contortions of our savage guests. The women are getting bold by this time, and come in considerable numbers, bringing us their simple offerings of friendship. They are the queerest creatures imaginable, and dirty beyond all description. Yet there is no small degree of coyness about them, which makes them interesting, in spite of their red-stained lips and unwashed legs. They wear the most marvellous girdles of loose rings of ratan split to the thickness of a thread, and a belt covered with cowries. The ears are pierced with big holes, in which they insert silver tubes six inches long, adorned with tufts of red cloth. We have been trying to-day to tempt them to sell these strange ornaments for dazzling bead necklaces, but to no purpose. One creature permitted me even to draw a tube out of her ear, but my attempts at bargaining only produced good-humoured laughter from the men and giggles from the women.”

The curious crowds became at last so troublesome that we were obliged to close the mat screen in front of our entrance hall, to secure ourselves from the intruders who wished to watch us at our breakfast. The excitability of their nature was exemplified when the Sikhs were paraded at rifle and revolver practice at a target. The Kakhyen eye-witnesses shouted and flourished their muskets, and some sprang to the front blowing their matches, and indicating that they wished to try their skill. The Burmese officers had to restrain them, and afterwards the pawmines came forward, and formally asked the tsare-daw-gyee to permit them to fire at the targets, at the same distance, three hundred yards. This was refused, and the excitement gradually subsided. The Burmese said that it all arose from the fact that a Kakhyen cannot even hear a gun fired without instantly discharging his own piece, if only in the air.

On February 14th the Ponsee pawmine arrived to inquire when we would start, and was informed that we were ready to set out at once. Thereupon a conference of chiefs took place under a sort of cotton tent or canopy, which had been erected by the Burmese, apparently from mistrust of the ability of our floor to bear a crowd. It was then decided that we should march on the 16th, as the Burmese wished that a Chinese caravan should precede us. The tsare-daw-gyee remarked that if the Kakhyens intended to attack either party, he would give them the opportunity to do both, to avoid mistakes. He reported that orders had been received at Manwyne, from the governor of Momien, that the English mission was to be treated “according to custom,” of which phrase no one could furnish any explanation. In the night we were alarmed by what seemed to be an apparent stampede of mules, and a prodigious shouting from the Burmese guard. It turned out that a buffalo which the Kakhyens were slaughtering had broken loose, with its throat gashed, and after a chase had been despatched just opposite our khyoung, where in the morning they were cutting it up, having fixed the head on a post of the zayat, probably in our honour as founders of the feast. At noon, the tsare-daw-gyee appeared, accompanied by a tsitkay-nekandaw, or deputy, from Bhamô, who had been sent by the Woon to report progress. The official activity was stimulated by the fact that the officer who had been sent up with us to Mandalay, and had returned thither, had been condemned to banishment in chains to Mogoung, because he had not waited to see us off. As the poor old man had returned with our consent, and was in bad health, our leader wrote to Mandalay to intercede for his pardon, which was subsequently granted by the king. The tsitkay-nekandaw afforded a curious illustration of a custom mentioned by Colonel Yule.[40] The upper part of his cheeks was disfigured by large swellings, caused by the insertion under the skin of lumps of gold, to act as charms to procure invulnerability. Yule mentions the case of a Burmese convict executed at the Andaman Islands, under whose skin gold and silver coins were found. The stones referred to in the text of Marco Polo, as well as the substances mentioned in the note by his learned editor, do not appear to have been jewels. The custom prevails among Yunnan muleteers of concealing precious stones under the skin of the chest and neck, a slit being made, through which the jewel is forced. This, however, is not to preserve the owners’ lives, but their portable wealth. While at Mandalay, I examined some men just arrived from Yung-chang, and found individuals with as many as fifteen coins and jewels thus concealed, as a precaution against the robbers who might literally strip them to their skin, without discovering the hidden treasure. But our Burmese official regarded his disfiguring gold as a certain charm against danger.

During our interview with the Burmese, some of the pawmines came to receive an advance of one-third of the mule hire, which was paid them; and then Sala appeared to definitely agree on the amount of toll. One of the other chiefs was asked to be present, but he preferred leaving it to Sala’s decision. The latter agreed to receive five rupees per mule, and was most careful to keep off any inquisitive hillmen while he was debating, and afterwards receiving the whole amount. As all baggage was ready, save such articles of bedding, &c., as were daily in use, the next day was fixed for the actual departure. Browne, as a final preparation, distributed red turbans to the Burmese guard, which gave something of a uniform appearance to the otherwise motley horde.

We rose at 6 A.M. on February 16th, and made all our personal baggage over to the Kakhyens, who were slow in completing their preparations for a start. The Ponsee pawmine first appeared, and the burden of his complaint, conveyed in the strongest affirmatives, and with most expressive pantomime, was that he had not received any of the blackmail, all the payment having been appropriated by Sala. The tsare-daw-gyee declared that the latter had been obliged to disgorge his plunder, but as a precaution he should be kept as a hostage at Tsitkaw. A difficulty then was occasioned by the size of the box of edible birds’ nests, which no muleteer would take; settlement of this was left by Colonel Browne to the Kakhyen chiefs. A sharp dispute relative to the method of taking the tallies of the number of the mules broke out between the “Death’s Head” pawmine of Ponsee and the Burmese choung-oke. This ran so high that the pawmine threatened to shoot the choung-oke, and the old Burman swore he would cut down the Kakhyen, but the contest resolved itself into abuse, and the Burman prevailed by strength of lungs. A discussion then arose between the Ponsee pawmine and another, whose contingent of mules the former was desirous of reckoning, wholly or in great measure, amongst his own.

The muleteers, having been delayed by the squabble, unloaded their animals and drove them off to graze; the regathering of them was a work of time, but they at last filed off, preceded by Margary and Allan with a division of the Burmese guard. The rest of the mission, however, was retarded by the difficulty of finding porters for the rejected box of birds’ nests, the medicine chest, and photographic apparatus, all of which had been left out in the cold, and had to be carried by Burmese. At four o’clock, we finally cleared out of Tsitkaw, watched by Sala, who waved an adieu from the porch of the house where he was to reside as a hostage for our safety. We observed by the roadside several women sitting with carafes of water, each containing a flower, from which they poured libations as they muttered prayers for our safety. As we passed the succeeding villages of Hantin, Hentha, and Myohoung, the road was lined with women similarly occupied. An hour and a half of slow progress brought us to the hamlet of Tsihet, at the foot of the hills, outside of which men awaited us with welcome draughts of pure and cool water. There are two small villages, each within its own stockade, separated by a space of thirty yards. We took up our quarters in a rickety zayat within the northernmost village. The camp outside presented a most busy scene. Burmans were cooking their dinners, while others were erecting temporary huts of freshly cut bamboos, or thatching them with bamboo leaves and long grass. Groups of Kakhyen muleteers, who had arrived first, were sitting in their huts, smoking and chatting; others were collecting and marshalling the mules in lines between the baggage, each animal having one of its feet fastened to a wooden peg driven into the ground. The Burmese had encamped in a cordon enclosing the Sikhs and Kakhyens, and of course all the baggage; and outposts had been established at the north and south of the village.

The locality of Tsihet, owing to the proximity of the hills, appeared to be unhealthy, and the children looked very sickly. This is not to be wondered at if the ordinary supply of water was to be judged by that furnished to us in the evening, which seemed to have come from a buffalo wallow. All the villagers assembled to watch the kalas at their al fresco dinner, and eagerly accepted our empty bottles, which were regarded as precious prizes.

At eight o’clock next morning we were in motion, and almost immediately began to ascend, crossing a succession of ridges, till at 9.30 the first Burmese kengdat, or guard-house, was reached, called Pahtama Kengdat. It is situated in a hollow, and, like the rest, consists of a small house built of teak and bamboo, raised on piles, and surrounded by a double bamboo stockade, with two poles bearing white pennants raised in front. The garrison consisted of some half-dozen Burmese soldiers. Still ascending, we reached the district of Singnew and at a place where the road diverged, several Kakhyen men and women had collected to see us pass. The second Burmese guard-house, or Lamen Kengdat, and soon afterwards the village of Pehtoo, or Payto, were passed, and we entered the territory of Ponline. From the first village and the third guard-house, Tap-gna-gyee, we ascended to the principal village and residence of Sala, called Lankon, where we spent our first night in Kakhyen land in 1868.[41]

We halted at noon in front of the chiefs house, by which grew a fine peach tree in full bloom. A few old Kakhyens were assembled, and among them the tsawbwa-gadaw, who produced sheroo, and demanded payment, receiving four annas, with which she seemed very dissatisfied. The road, or rather track, no wise improved during the last seven years, was marked on either hand by tufts of raw cotton which the lower hanging branches had taken as toll from the frequent caravans. From this village our route lay to the north of that formerly travelled by us, and a descent of an hour brought us to a small stream called Moonam, on the other side of which we found the camp formed on a slope which had evidently been recently cleared for the site of the fourth guard-house, named Tsadota Kengdat, surrounded by high hill spurs on all sides. We put up in the guard-house, which occupies the highest point of the slope, and the Burmese formed their usual line round the Kakhyens. The tsare-daw-gyee made his appearance later, having followed a different route, which brought him to the north-eastern end, where he encamped his party. All around us during the evening we heard the gongs answering each other, and the loud shouts, or “All’s well!” of the Burmese outposts.

After a refreshing bath, we took a stroll up the hill under the guidance of a Kakhyen to look for pheasants, from which we brought back nothing but a portion of an enormous fungus. Before bedtime, Browne announced that a Kakhyen had come to him with the information that four hundred evil-disposed Kakhyens had assembled themselves beyond Ponsee to dispute our advance. More friendly visitors were promised in the shape of the tsawbwa-gadaw of Woonkah and her followers, who were expected to arrive in the morning from her husband’s village, situated on the mountain to the north of Ponline.

While waiting in the morning of February 18th for the arrival of our expected visitors, the tsare-daw-gyee with his subordinate officers appeared, and in a very serious tone repeated the information that four hundred evil-disposed Kakhyens and Chinese hill dacoits had taken obligations among themselves to attack us, probably for the sake of plunder. The amount of credence to be given to the report was variously estimated, both by Kakhyens and Burmese. Moung Mo and Moung Yoh disbelieved it; but the former wretched old man became suddenly unwell, to such an extent that he feared he would be unable to go forward. The Ponsee pawmine scouted the story, and averred it to be an invention of a worthless Kakhyen who met us yesterday. Our Sikh havildar promptly volunteered to advance with his fifteen men, and clear the road of any number of these mountaineers, whom his observations at Sawady and elsewhere made him hold very cheaply. The tsare-daw-gyee declared that he and his men were ready to fight, but that it was desirable to advance peaceably if possible. It was finally decided that we should proceed to the last Burmese guard-house on the banks of the Nampoung, and the caravan set out about nine o’clock.

After a short, steep ascent, within hearing of the roar of the distant Tapeng, the road descended to the Nampoung. Passing over two short ridges, whence a magnificent view of the glen running south-south-west to north-north-east is obtained, and then traversing a steep path in a succession of narrow zigzags to the banks of the stream, we arrived at the fifth Burmese guard-house by 10.30 A.M.

The valley of the Nampoung is a deep, narrow glen, bordered on either side by high mountains, and in no place is it broader than two hundred yards. The river is a rapid clear stream, flowing in a rocky channel between rock-strewn flats edged by high grass on either side. The banks rise abruptly, covered with lofty forest trees, tangled with magnificent creepers and festooned with orchids. Some miles to the north a rather treeless valley communicates with the glen, apparently running in a direction behind Manwyne. The guard-house occupies a level open space, covered with terraces of paddy cultivation. To the south the glen terminates in a deep gorge, down which the river rushes to the Tapeng. We found the encampment formed, and the people, as usual, busily preparing their huts, as, notwithstanding the advice of the Ponsee pawmine, that we should proceed to Shitee, it had been decided that we should remain here.

Another Burman had arrived from Manwyne, confirming the report of danger ahead, but Margary discredited it, and expressed his readiness, if necessary, to proceed to Manwyne to inquire into the truth of the rumoured opposition. The tsare-daw-gyee approved of this step, and it was decided to send Margary forward, as he was known to the Manwyne people from his recent stay at that town, and to all the Chinese officers in the district as being under the protection of the viceroy of Yunnan.

During the afternoon gongs and cymbals were heard beating high up the hill on the Chinese or left side of the valley, and Kakhyens were seen peering down at us from among the trees. These proved to be the followers of the Shitee Meru tsawbwa, who, however, would not come across into Burmese territory, and after some time distant shots announced his return to his village. In the evening the encampment presented a picturesque scene, the red turbans of the Burmese combining with the rich greenery of the palm leaves which thatched the numerous huts. The Ponsee pawmine had erected for himself a wigwam of feathery palm fronds, and the gleam of the bright fire, round which a group of men in blue were chatting and smoking, lit up a picture that one longed to sketch.

We had a farewell dinner in the evening, to which Margary’s Chinese writer was invited. Our discussion of the prospects of the mission, though clouded by no anticipations of the fearful fate to which our gallant comrade was about to set out, lasted till a late hour, while the gongs of the watchful Burmese sounded as usual from various points all round our position.

Margary started for Seray en route for Manwyne early in the morning of February the 19th. He was accompanied by his writer, Yu-tu-chien, of whom I have already spoken, an intelligent Chinese Christian, who during his stay with us had made himself both liked and respected. The other attendants were his official messenger, or ting-chai, Lu-ta-lin, from the consulate at Shanghai; his boy, Ch’ang-yong-chien, known by the name of Bombazine; Li-ta-yu, a servant from Sz-chuen; and his cook, Chow-yu-ting, a native of Hankow, all of whom had accompanied their master in the journey across China. Besides his followers, Moung Yoh, or Li-kan-shin, and a pawmine of Seray, of by no means prepossessing appearance, and remarkable for a peculiar loud voice, escorted him to Seray.

The morning was devoted by myself to an attempt under the guidance of a Kakhyen to explore the valley, which was rendered difficult by the dense jungle, and the unwillingness of the native to proceed more than two or three miles from the camp.

The reports of threatened opposition were as rife as ever; but some Chinese who arrived during the day professed ignorance of any uneasiness among the hill tribes. A Kakhyen was brought in by the Burmese to the guard-house, who had come from Manwyne on the previous day on purpose to tell us, at some risk to himself, that a body of men had been collected to attack us, by one Yang-ta-jen, in league with the Seray tsawbwa. The messenger seemed half-witted, but was clear in his story, which certainly agreed with the previous reports. News arrived that all the hostages detained at Tsitkaw had escaped with the exception of Sala. One of them was the son of the Ponsee pawmine, and his father, who had been detailed to accompany Margary, was kept back to be sent to Tsitkaw in place of his son. The tsawbwa-gadaw of Woonkah duly arrived with her gift of fowls, eggs, and sheroo, and received broadcloth and other presents, with which she speedily disappeared, not without grumbling that she had not been paid in money for her fowls!

Nothing further occurred till next morning, when messengers brought a letter from Margary, dated from Seray, announcing that so far the road was unmolested, and all the people met with were civil, and that he should proceed to Manwyne. He noted that when in the Seray chief’s house, the Seray pawmine evinced his contempt for the Burmese by spitting on the ground.

On the strength of this communication, although the tsare-daw-gyee urged that no movement should be made until the news of Margary’s reception at Manwyne reached us, Colonel Browne resolved to proceed at once, and, if possible, reach that town in one march. The camp was accordingly struck, and, crossing the Nampoung, we entered China.

The road we were to pursue led straight up a steep spur of the main range dividing the Tapeng from the Nampoung, the highest point of which, Shitee Meru, rises immediately to the north of Ponsee, the position of the long detention of the first expedition of 1868. I set out in advance of the rest, accompanied by my men and the Kakhyen scout who had brought the information from Manwyne. The ascent commenced directly from the Nampoung valley, and three hours’ climb of the hill-path brought us to the first Shitee village at noon. The tsawbwaship has been divided among three brothers, each having a village of his own, but the youngest, according to Kakhyen rules, being the chief of Shitee Meru. At the first village we were hospitably received and refreshed with sheroo, and the children were delighted with beads and small coins. Here we found a native of India, a slave, who had come from beyond Assam, and had forgotten most of his language, but made himself known by calling out pani. On the hillside I met the Shitee Meru tsawbwa coming down with two men, one of whom escorted me some way; and next appeared the Wacheoon tsawbwa with a party of forty armed followers, some of them mounted on ponies. He was very friendly, and sent an escort back with us, one of whom had brought a lizard for the Englishman. The road wound up and over the spurs running down from the backbone of the Shitee-doung to the Nampoung, which flows from the north-east along a valley lying below the north-western slope of the main range that defines the right bank of the Tapeng. The greatest height reached on Shitee Meru Doung was about five thousand seven hundred feet above the sea, from which we descended slightly to the site chosen for our encampment, the altitude of which was found to be five thousand five hundred feet, where we halted at 3.30, after a march of about eight miles.

Between two rounded ridges running down to the Nampoung, one in our rear covered with forest, and the other with grass, about five hundred yards distant to the north-east, extended two flat clearings, where the caravans were accustomed to bivouack, the first and smaller clearing being close to the western spur. On the second and larger space, divided from the first by a mountain stream, and lying at a somewhat higher elevation, immediately along the grassy spur, the camp was pitched. Around and above the encampments the forest had been cleared, and the open space was covered with high grass interspersed with boulders. Just below the encampments the ground sloped abruptly into a grassy hollow between the ridges, which served as a grazing ground for the mules. The main mountain ridge, which rose to a height of six hundred feet above us, was clothed to its summit with dense forest, which formed a continuous covert, extending along the projecting ridge in the rear, and thus enclosing and commanding our position on the south and east. Below the hollow, the hillside, clothed with impenetrable jungle, sank abruptly to the Nampoung. The country over which the road wound along the slope, in the direction of Seray, consisted of old clearings covered with jungle grass and patches of uncut forest. The immediate exit of the road led through a depression in the ridge, and descended the intervening hollow, and, thence reascending, crossed the next spur.

We bivouacked in the open among the mules and baggage, and surrounded by the fires, the smoke from which was at first most intolerable, but no other annoyance or disturbance was experienced, and our Kakhyens enjoyed themselves listening to the melodies of a musical-box, which had become an especial favourite with them. The Burmese were as vigilant as ever, and their sentinels seemed to be on the alert all night. The tsawbwas of Wacheoon and Ponwah visited the camp, and they had heard nothing of any suspicious movements of troops, and the other Shans who brought fowls for sale confirmed this. Our interpreter, Moung Yoh, returned to the camp in company with the Seray men, the latter being remarkably well dressed and equipped, and evidently old acquaintances of the Burmese. He reported that the Seray chief was dissatisfied on account of the payment of the mule tax or dues to Sala, which, however, had been done with the knowledge and approval of the son of Seray. Moung Yoh then suggested that presents should be sent to Seray, whom he had discovered to be a great friend of his uncle, Li-sieh-tai, and to whose house he returned the same evening to await our arrival.

We were in readiness to start by seven o’clock in the morning of the 21st, but the tsare-daw-gyee intimated that he did not think it prudent to move until the tsawbwas of Shitee Meru, Woonkah, and others arrived. His real intention, however, was to remain in this camp until definite news came from Mr. Margary; but as the arrangement had been made with the latter that we were to advance if we did not hear from him warning us to the contrary, Colonel Browne resolved to push forward to Seray with the Sikhs, leaving the Burmese guard and caravan to follow. I started with my men in advance, but in a short time was overtaken by Browne, Allan, and Fforde, followed by the Sikhs and their servants, with the two led horses, the camp having thus been left to the Kakhyens, under the charge of the Burmese. Their cavalcade soon outstripped my party, as we were shooting, and collecting plants. The road lies over numerous spurs and through deep wooded hollows, and then crosses the watershed dividing the Nampoung valley from the gorge of the Tapeng; on the southern or Manwyne side of the ridge lies the district of Seray. Here a Shan Burman, wearing the red turban of our escort, accompanied by a Kakhyen, overtook us, and by signs gave me to understand that the tsare-daw-gyee wished us to return. As none of us could speak Burmese, I signed to him to proceed quickly and communicate his news to Colonel Browne, which he did, and I ordered my men to press forward to overtake the rest of the party, while I waited behind for my groom and pony. The messenger on his return signified that Colonel Browne was continuing his progress to Seray. The road descended into a hollow, from which a steep ascent leads to Seray. Here a difficulty arose about the road, as several paths diverged, and there was nothing to indicate which had been taken by Colonel Browne’s party. Unfortunately, I took a wrong one, and soon arrived at a strange village, the inhabitants of which had, doubtless, never before seen an European. According to Kakhyen custom, I dismounted before entering, and, seeing some women standing at the door of the first house, indicated by signs that I desired to know the road. They sulkily waved to me to go on upwards. Imagining that the end of the village was reached, I prepared to remount, but this was resented by a number of men who rushed out of a house, and, shouting, drew their dahs in a threatening manner. I tried to induce some of them, by the offer of compraw, to show me the way, but none would do so. Proceeding onwards, followed by the hillmen, I suddenly found my big dog by my side. As his presence was evidence that some of my men were behind, I turned my pony’s head, and all the Kakhyens bolted. After retracing my steps for some distance, I discovered my collectors and servants hiding for fear in a deep hollow. Presently I met a Kakhyen boy, who conducted us to the village of Seray.

Seray, like the majority of Kakhyen villages, is finely situated on the summit of a ridge, among lofty trees, enclosing a grassy glade in its centre. The paths approaching the village are broad, and its vicinity is indicated by groups of high massive wooden posts, with simple devices in black, and by groves to the nats, and by small circular walled enclosures devoted to the worship of the sky spirit. On arriving, I found all the Sikhs ranged in front of the tsawbwa’s house, also the chiefs of Woonkah and Wacheoon, and Allan’s Chinese clerk. It was so dark on entering that at first I could not recognise Colonel Browne, Allan, and Fforde, save by their voices. The chief, who knew me again, was seated on the ground, and it was observable that he and all his men were armed. The restlessness which he exhibited, his withdrawing outside for private conferences with his pawmine, and the fact that all the women had left the house, excited suspicion; but when the latter returned, and the chief and his pawmine divested themselves of their dahs, I concluded that any hostile intention that might have been originally entertained against us had for the present been abandoned. Then sheroo and hard boiled eggs were brought in and set before us; but further parley with the chief produced no results, and we adjourned to a grove of oak and hazel trees on the outskirts of the village. Moung Yoh, or Li-kan-shin, the professed nephew of Li-sieh-tai, who had been acting as our interpreter, and addressing Seray as uncle as a mark of friendship, presently came to request Colonel Browne to return to the chief’s house. There it was decided that the Seray and Woonkah tsawbwas should proceed to Manwyne at once, and ascertain the actual state of things, and take a letter to Margary. Another Burman had arrived from the camp to request us to return, and we mounted our ponies, and retraced our steps. On the road we met some Kakhyens, one of whom seized the bridle of Browne’s horse, and signed him to go back, as the road was beset, but as our friend was under the influence of sheroo, we spoke to him pleasantly and proceeded. This man was a pawmine of Shitee, who returned to the camp in the evening, and, when taxed with having been intoxicated, admitted that he had started with a bamboo flask full of sheroo, which he had finished. These incidents showed that there was an uneasy apprehension of danger, but that in the immediate vicinity the Kakhyens were friendly.

During our absence, the Burmese had thrown up barricades or breastworks of stones and earth, at points above the camp, and commanding the road to Seray. The tsare-daw-gyee announced to Browne that we should certainly be attacked by the Chinese either that evening or on the march the next day. Some men were observed peering down from among the trees on the hill-brow, as if reconnoitring our position. The Burmese, who were collecting firewood, came running down as fast as they could, and the whole camp set up a fearful shout to scare the supposed enemies, who disappeared, and the excitement gradually subsided.