CHAPTER NINE

CORAL SEA

After Pearl Harbor, the Japanese aimed to invade New Guinea and the Solomon Islands. U.S. forces, aided by some Australian ships, moved to intercept them. This produced the first naval battle fought at long range between aircraft carriers. Dive bombers and torpedo bombers attacked ships protected by screens of fighters. It was a novel and confusing form of warfare, with both sides struggling to find the enemy and unclear about what ships they had seen and engaged. The most serious loss was the American carrier USS Lexington, scuttled after catching fire. The fight forced Japan to call off its invasion plans.

In the spring of 1942, following their rapid successes during the early months after their entry into the war, the Japanese were ready to extend their control over the Coral Sea by capturing Port Moresby in New Guinea; thus isolating Australia from Allied help and opening the way for further advances in the southwest. The battle which ensued was the first naval battle to be fought entirely by aircraft; no ship on either side made visual contact with the enemy.

The Japanese had made great gains in the vast Pacific Ocean. The conquest of the Philippines, Burma, Malaya and the Dutch East Indies had cost the Japanese Navy only 23 warships and none had been larger than a destroyer. 67 transport ships had also been lost. The Japanese naval command had expected far greater losses, therefore, encouraged by such success, they looked to expand still further in the Far East. However, the senior officers in the Japanese Navy disagreed on what was the best way forward.

The very success which the Japanese had achieved in implementing their initial war plans had raised a fresh series of questions in the minds of those responsible for shaping Japanese naval strategy. And had caused a fierce and prolonged debate among the higher echelons of the Japanese naval command.

The Naval General Staff, headed by Admiral Nagano, advocated either an advance westward against India and Ceylon, or a thrust southward towards Australia. Admiral Yamamoto and the staff of the Combined Fleet, on the other hand, argued that a prolonged struggle would be fatal to Japanese interests, and regarded the first priority as being the destruction of the United States aircraft-carriers in the Pacific, to maintain Japanese security in the area. To this end, they urged early operations against Midway, to the eastward, seeing this as necessary for an attack on Hawaii. With the presence of the Combined Fleet in Hawaiian waters to support an invasion, the United States fleet would certainly be drawn out into a decisive battle, and could be dealt with before the Allies brought their emerging superior resources to bear against Japan.

The Japanese army, with its eyes on the Asian mainland and on Russia, objected to committing the large numbers of troops needed for the Naval General Staff's plans, and forced the latter to work out a more modest scheme. This involved moving from Rabaul and Truk, where Japanese forces were already firmly entrenched, into Eastern New Guinea, and down the Solomons and New Hebrides to New Caledonia, the Fijis, and Samoa.

In theory, the formulation of Japanese strategy was the responsibility of the Army and Navy General Staffs, operating jointly as sections of Imperial General Headquarters. In practice, however, the ability of the Combined Fleet to influence strategy had been demonstrated by Yamamoto's insistence on the Pearl Harbour operation, despite the opposition of the General Staff. Subsequent events served to reinforce that influence.

It was the Americans who forced the hand of the Japanese. On the 18th April 1942, the Doolittle raid on Tokyo, launched from the aircraft-carrier Hornet, inevitably strengthened Yamamoto's case for the Midway operation, particularly in the failure to keep the capital itself immune from bombing attacks. The opposition of the General Staff promptly vanished. By 5th May, Admiral Nagano, Chief of the Naval General Staff, and acting in the name of the Emperor, issued Imperial General Headquarters Navy Order 18 which directed Yamamoto to; 'carry out the occupation of Midway Island and key points in the Western Aleutians in cooperation with the army’. The operation to take place early in June.

However, the Japanese had decided on a course of action that spilt their forces. The attack on New Guinea had already started and could not be called off as it was too far advanced. Therefore, Yamamoto could not call on all the forces he might have needed for an attack on Midway Island as some Japanese forces were concentrated in the Coral Sea to the south-east of New Guinea. Thereby forcing upon the Japanese two concurrent strategies which were destined to over extend their forces. The plan for the impending Operation 'MO' was based on simple premises, but was over elaborate in the detail by which it was to be carried out. In fact this plan was too complicated, revealing a typical weakness which was evident throughout the war. It demanded a level of tactical competence which the Japanese did not possess. The division of forces in the plan might well be fatal to its prospects of success, should the Japanese meet a determined enemy when they were not in a position to concentrate and coordinate the separate units effectively.

The occupation of Port Moresby had originally been scheduled for March, but the appearance of American carrier forces in the south-west Pacific had caused the Japanese to postpone the operation until early in May, so that the V Carrier Division of the Nagumo force, then returning to Japan after the Indian Ocean operations, could be used to reinforce the IV Fleet at Truk and Rabaul. The V Carrier Division, under Rear-Admiral Hara, contained the powerful aircraft-carriers Shokaku and Zuikaku. A number of heavy cruisers which had seen service in the Indies were also spared for the invasion, together with the light aircraft-carrier Shoho from the Combined Fleet. The remainder would have to be furnished by the IV Fleet, under Vice Admiral Inouye, who was given overall command of the operation.

The next encounter, the Battle of the Coral Sea, came about because Admiral Yamamoto's cherished decisive battle had not yet come about. His strategy had worked well so far, the US Pacific Battle Fleet had been destroyed and a chain of Island bases had been established to protect the new conquests. But still the American carriers eluded him, as the Doolittle raid on Tokyo showed only too clearly. It was recognised by the Army that Australia was an important base for any counter-offensive aimed at their own base at Rabaul. Yamamoto did not believe that the South-western Pacific would provide the decisive battle (his staff was planning for that in a strike against Midway), but he acquiesced to the Army's plans. It all looked so easy to him after the staggering series of victories and the Japanese were becoming drunk with success.

The operation included an amphibious invasion of Port Moresby and the capture of Tulagi in the Solomons. The Japanese labelled the attack on Port Moresby as ‘Operation MO’ and the force that was to attack it was 'Task Force MO'. The main part of the Japanese plan was to move through the Jomard Passage, to the south-east of New Guinea, allowing it to attack Port Moresby.

The organisation of Task Force MO, which was to execute the plan, comprised:

-

The Port Moresby Invasion Group of 11 transports, carrying both army troops and a naval landing force, which, screened by destroyers, were to come down from Rabaul and around New Guinea through the Jomard Passage;

-

A smaller Tulagi Invasion Group for setting up a seaplane base there;

-

A Covering Group, under Rear Admiral Goto, consisting of the Shoho, four heavy cruisers, and one destroyer, which was to cover the Tulagi landing, then turn back west to protect the Port Moresby Invasion Group;

-

The Striking Force, commanded by Vice Admiral Takagi, and containing the Shokaku and Zuikaku, which was to come down from Truk to deal with any United States forces that might attempt to interfere.

The Carrier Strike Force left Truk on 1st May and by the afternoon of 5th May it was in position. Its opposition was Task Force 17 with the aircraft-carriers Lexington and Yorktown. The Americans had a slight edge over the Japanese in aircraft. They also had radar, but above all they had the benefit of superior intelligence about the Japanese dispositions.

Since Pearl Harbor, the United States had succeeded in completely breaking the Japanese naval code, and therefore possessed accurate and fairly detailed intelligence concerning the Japanese plans. Not only had the Americans broken the code, so that Admiral Nimitz and his staff knew exactly what the Japanese objectives would be, but there was a constant flow of reports from the Australian' Coast watcher’s', who reported sightings of Japanese ship movements.

Naturally, Inouye expected opposition from the Allied forces in the south-west Pacific. He knew that about 200 land-based aircraft were operating from airfields in northern Australia, and that American air activity made the concealment of ship movements difficult. However, he estimated that Allied naval forces in the area were 'not great', and that only one aircraft-carrier, the Saratoga, would be available. He hoped that the prior occupation of Tulagi, due to be taken on May 3rd, and the establishment of a seaplane base there, would make it more difficult for the Allies to follow his movements from their nearest bases at Port Moresby and Noumea. The Support and Covering Groups and the Striking Force would cover the Port Moresby Invasion Group which would leave Rabaul on 4th May, and land a sizeable force on the seventh. Once the Allied task force entered the Coral Sea, Inouye thought he could destroy it by a pincer movement, with Goto on the west flank and Takagi on the east, while the Invasion Group slipped through the Jomard Passage to its destination. With the Allied force out of the way, he could then proceed with the bombing of bases in Australia

To the Allies, Port Moresby was vital not only for the security of Australia, but also as a springboard for future offensives in the south-west Pacific. Admiral Chester Nimitz, Commander-in-Chief of the United States Pacific Fleet (CINCPAC), and General Douglas MacArthur, Commander-in-Chief Southwest Pacific Area, thus gave the threat the attention it merited. Before 17th April, reports had reached CINCPAC headquarters that a group of transports, protected by the light aircraft-carrier Shoho and a striking force that included two large aircraft-carriers, would soon enter the Coral Sea. By the 20th Nimitz had concluded that Port Moresby was the objective, with the attack likely to develop on or after 3rd May.

It was one thing to know the nature of the task, but yet another to be able to summon up the resources to meet the situation. The Saratoga was in fact still in Puget Sound undergoing repairs for torpedo damage sustained in January. The aircraft-carriers Enterprise and Hornet did not return from the Tokyo raid until April 25th, and were unlikely to reach the Coral Sea in time to participate in the coming battle, bearing in mind that they needed a minimum of five days for upkeep, and Pearl Harbor was about 3 500 miles away.

The problem with the American command structure was the rigid demarcation of command between Nimitz and MacArthur, according to the decision of the Combined Chiefs-of-Staff, whereby CINCPAC could exercise control over all naval operations in the Pacific, but could not usurp MacArthur's command of ground forces or land-based aircraft within the latter's area. Thus Nimitz could not readily call upon the 300 odd land-based aircraft of the USAAF and the RAAF for air searches in the area. Inouye, on the contrary, had the XXV Air Flotilla at Rabaul, as well as all seaplanes, under his control.

Knowing, however, that he would have to rely mainly on air strike to frustrate Inouye's plans, Nimitz decided to utilise what' remaining aircraft-carrier strength was available to him. For this task, he called upon the air groups of the Yorktown and Lexington. The Yorktown task force (No. 17) included 3 heavy cruisers, 6 destroyers, and the tanker Neosho.

The Lexington task force (No. 11) was fresher, having left Pearl Harbor on 16th April, after three weeks’ maintenance. With the 'Lady Lex', as she was affectionately known, were 2 heavy cruisers and 5 destroyers. Commanded by Captain Sherman, the Lexington could truly be called a happy ship; many of her crew had served with her since she was commissioned in 1927, while her air group included such notable naval aviators as 'Butch' O'Hare and John Thach. Rear-Admiral Aubrey Fitch, a distinguished carrier-tactician, had been on the flag bridge since 3rd April. Task Force 17, with the Yorktown, was commanded by Rear-Admiral Frank Fletcher, and had already been in the area for two months.

Task Force 1, operating out of San Francisco, consisted mainly of pre-war battleships; these were simply not fast enough to keep up with the aircraft-carriers, nor could the oilers be spared to attend to their fuel requirements. All that remained were the ships of task Force 44; commanded by Rear Admiral Grace, RN. Of these, the Australian heavy cruisers Australia and Hobart, then in Sydney, were ordered to rendezvous with Fletcher in the Coral Sea on 4th May. The heavy cruiser USS Chicago and a destroyer were ordered to join the same commander three days earlier, on 1st May.

On 29th April, Nimitz completed his plans. These simply detailed Fletcher to exercise tactical command of the whole force, designated Task Force 17, and ordered him to operate in the Coral Sea commencing 1st May. The manner in which Inouye's threat was to be met was left almost entirely to Fletcher.

Fitch's Lexington force joined Fletcher as planned at 06 30 hours on 1st May, and immediately came under Fletcher's tactical command. At 07 00 hours, Fletcher commenced refuelling from the Neosho, and directed Fitch to do the same from the Tippecanoe, a few miles to the south-west. Fitch had estimated that this task would not be completed until noon on the 4th, whereas Fletcher would finish 'topping up' by 2nd May. In the light of reports of the enemy's approach, Fletcher decided that he could not wait for Fitch and Grace, and steamed out into the middle of the Coral Sea to search for the Japanese. He headed west on the 2nd, leaving orders for Fitch to rejoin him by daylight on the fourth.

By 08 00 hours on 3rd May, Fletcher and Fitch were over 100 miles apart, each ignorant of the enemy's detailed movements. In fact, the junior flag officer was to finish fuelling by 13 10 hours, but could not break radio silence to tell Fletcher of this fact, and instead headed towards the planned rendezvous. At 19 00 hours the Yorktown force, now out on a limb, received the report which Fletcher 'had been waiting two months' to hear: the Japanese were landing at Tulagi.

The news brought about an immediate change in Fletcher's plans. Ordering the Neosho and Russell to peel off and meet Fitch and Grace at the appointed rendezvous, then proceed with them in an easterly direction to rejoin Yorktown 300 miles south of Guadalcanal on 5th May. Fletcher headed north at 24 knots, determined to strike Tulagi with the Yorktown's available aircraft. Maintaining his course throughout the night, he arrived at a point about 100 miles south-west of Guadalcanal at 07 00 hours on the fourth. By this time Fitch had received his new orders, while Grace, with Australia and Hobart, was nearing the rendezvous. Both were unable to help Fletcher in case of need, their south easterly course actually increasing the distance between them and the Yorktown.

Fortunately for Fletcher, the Japanese had estimated that, once Tulagi was in their hands, it would remain unmolested. Goto's and Marushige's groups, which had supported the operation, had consequently retired at 11 00 hours on 3rd May, after the island had been secured. Hara's carriers were still north of Bougainville, while the Port Moresby Invasion Group was only just leaving Rabaul. Furthermore, as Fletcher approached the launching position for his strike, he ran into the northern edge of an l00 mile cold front-which screened his warships, and afforded a curtain for his planes until they came within 20 miles of Tulagi, where fair weather prevailed.

First blood went to the Americans, when the invasion transports in Tulagi harbour were sighted. At 06 30 hours on 4th May, the first strike was launched from Yorktown, consisting of 12 Devastator torpedo bombers and 28 Dauntless dive-bombers. With only 18 fighters available for patrol over the carrier, they were forced to rely on their own machine guns for protection. According to the practice of the time, each squadron attacked independently. As so often happened during the war, the pilots overestimated what they saw, mistaking a minelayer, for a light cruiser, minesweepers for transports, and landing barges for gunboats. Beginning their attacks at 08 15 hours, aircraft of the two Dauntless squadrons and the Devastator squadron were back on Yorktown by 09 31 hours, having irreparably damaged the destroyer Kikuzuki and sunk 3 minesweepers, including the Tama Maru. A second strike later destroyed 2 seaplanes and damaged a patrol craft, at the cost of one torpedo-bomber; while a third attack of 21 Dauntlesses, launched at 14 00 hours, dropped 21 half-ton bombs, but sank only 4 landing barges.

By 16 32 hours the last returning aircraft were safely landed on the Yorktown, and the 'Battle' of Tulagi was over. Only 3 aircraft had been lost, the other two being Wildcat fighters which had lost their way returning to the aircraft-carrier and had crash-landed on Guadalcanal, the pilots being picked up that night by the Hammann. But, in the words of Nimitz: “The Tulagi operation was certainly disappointing in terms of ammunition expended to results obtained”.

Nevertheless, a mood of considerable elation prevailed on the Yorktown that evening, the pilots believing that they had sunk 2 destroyers, 2 freighters, 4 gunboats, and damaged a third destroyer, and a seaplane tender. Fletcher headed the whole force south for his rendezvous with Fitch. Once again luck had been with him', for Takagi was by now making his best speed south-eastward from Bougainville, having received calls for help from Tulagi at noon that day. If Fletcher had not achieved complete surprise in his Tulagi strike, and Takagi had moved earlier, the Yorktown would have met the Japanese aircraft-carriers on her own, as Fitch was widening the gap between Fletcher and himself all through the daylight hours of the fourth.

The next day, the 5th, was a relatively uneventful one for both sides. Having rejoined Fitch and Grace at the scheduled point at 08 16 hours, Fletcher spent most of the day re-fuelling from Neosho, within visual signalling distance of the junior flag commanders on a south-easterly course. The ships were by now well out of the cold front and were to mostly enjoy perfect tropic seas weather for the next two days.

Meanwhile, the various components of the Japanese force were entering the Coral Sea. Admiral Takagi's Striking Force was moving down along the outer coast of the Solomons. By dawn on 6th May it was well into the Coral Sea. The Port Moresby Invasion Group and Marushige's Support Group were on a southerly course for the Jomard Passage, while Goto's Covering Group began re-fuelling south of Bougainville, completing this task by 08 30 hours the next morning. One four-engined Japanese seaplane, operating from Rabaul, was shot down by a Wildcat from Yorktown but, as Inouye did not know where it had been lost, he used most of his aircraft on a bombing attack on Port Moresby.

On the 6th, the tension grew, as both Fletcher and Inouye knew that the clash was bound to come soon. The American commander decided that it was now time to put into effect his operational order of 1st May, and accordingly redeployed his force for battle. An attack group, under Rear-Admiral Kinkaid, was formed from the four heavy cruisers, the light cruiser Astoria, plus five destroyers. The heavy cruisers Australia, Hobart, and Chicago, with two destroyers formed Grace's support group, while the air group, to be placed under the tactical command of Fitch during air operations, comprised the Yorktown and Lexington, and four destroyers. The oiler Neosho, escorted by the destroyer Sims, was detached from Task Force 17, and ordered to head south for the next fuelling rendezvous, which was reached next morning.

Throughout the 5th and 6th, Fletcher was receiving reports from Intelligence regarding the movements of Japanese ships of nearly every type; by the afternoon of the 6 th, a pattern was becoming evident to him. It was now fairly obvious that the Japanese invasion force would come through the Jomard Passage on the 7th or 8th, and Fletcher accordingly cut short fuelling operations, heading north-westward to be within striking distance by daylight on the seventh.

Owing to the inadequacies of land-based air searches, he did not as yet have any clear picture of the movements of Takagi's aircraft-carriers, or of the Japanese plan to envelop him. His own air searches had in fact stopped just short of Takagi's force, which was hidden under an overcast, having turned due south that morning, thus dropping down on Fletcher's line of advance. By midnight Task Force 17 was about 310 miles from Deboyne Island, near New Guinea, where the Japanese had established a seaplane base to cover their advance.

If the air searches of either side had been more successful, the main action of the Coral Sea might have taken place on 6th May. Takagi, amazingly, ordered no long-range searches on 6th, thus missing the opportunity of catching Fletcher while the latter was re-fuelling in bright sunlight. A reconnaissance aircraft from Rabaul did report Fletcher's position correctly, but the report did not reach Takagi until the next day. At one point he was only 70 miles away from Task Force 17, but ignorant of its presence. Thus when he turned north in the early evening, to protect the Port Moresby Invasion Group, he once more drew away from the United States aircraft-carriers.

Some elements of the Japanese force had, however, been sighted on 6th May. B-17 s from Australia had located and bombed the Shoho, of Goto's Covering Group, south of Bougainville. The bombs had fallen wide, but Allied planes spotted Goto again around noon, then turned south to locate the Port Moresby Invasion force near the Jomard Passage. Estimating that Fletcher was about 500 miles to the south-west, and expecting him to attack the next day, Inouye ordered that all operations should continue according to schedule. At midnight the invasion transports were near Misima Island, ready to slip through the Jomard Passage. Goto, protecting the left flank of the Port Moresby Invasion Group, was about 90 miles northeast. The Japanese were in an optimistic mood, for everything was going to plan, and that very day they had heard the news of the fall of the Philippines and the surrender of General Wainwright's forces on Corregidor.

Fortune indeed smiled on Fletcher that day. At 06 45 hours, when a little over 120 miles south of Rossel Island, he ordered Grace's support group to push ahead on a north-westerly course to attack the Port Moresby Invasion Group, while the rest of Task Force 17 turned north. Apparently Fletcher, who expected an air duel with Takagi's aircraft-carriers, wished to prevent the invasion regardless of his own fate but, by detaching Grace, was in fact weakening his own anti-aircraft screen while depriving part of his force of the protection of carrier air cover.

The consequences of this move might have been fatal, however, instead, the Japanese were to make another vital error by concentrating their land-based air groups on Grace rather than Fletcher's aircraft carriers. A Japanese seaplane spotted the support group, when the ships of Grace's force were south of Jomard Passage. Eleven single-engined bombers launched an unsuccessful attack. Soon afterwards, 12 Sallys (land-based navy bombers) came in low, dropping 8 torpedoes. These were avoided by violent manoeuvres, and 5 of the bombers were shot down. Then 19 high-flying bombers attacked from 15 000 to 20 000 feet, the ships dodging the bombs as they had the torpedoes.

Gato's Covering Group, had turned south-east into the wind to launch four reconnaissance aircraft and to send up other aircraft to protect the invasion force 30 miles to the south-west. By 08 30 hours Goto knew exactly where Fletcher was, and ordered Shoho to .prepare for an attack. Other aircraft had meanwhile spotted Grace's ships to the west. The result of these reports was to make Inouye anxious for the security of the Invasion Group, and at 09 00 hours he ordered it to turn away instead of entering Jomard Passage, thus keeping it out of harm's way until Fletcher and Grace had been dealt with. In fact, this was the nearest the transports got to their goal.

Fletcher had also launched a search mission from Yorktown. One of her reconnaissance aircraft reported 'two carriers and four heavy cruisers' about 225 miles to the north-west. Assuming that this was Takagi's Striking Force, Fletcher launched .a total of 93 aircraft between 09 26 hours and 10 30 hours, leaving 47 for combat patrol. By this time Task Force 17 had re-entered the cold front, while Goto's force lay in bright sunlight near the reported position of the two ‘carriers'. However, no sooner had Yorktown's attack group become airborne than her scouts returned, and it immediately became obvious that the 'two carriers and four heavy cruisers' should have read 'two heavy cruisers and two destroyers' - the error being due to the improper arrangement of the pilot's coding pad. Actually the vessels seen were two light cruisers and two gunboats of Marushige's Support Group. Fletcher, now knowing that he had sent a major strike against a minor target, courageously allowed the strike to proceed, thinking that with the invasion force nearby there must be some profitable targets in the vicinity.

The next day the battle began in earnest. Accepting Hara's recommendation that a thorough search to the south should be made before he moved to provide cover for the Port Moresby Invasion Group, Takagi accordingly launched reconnaissance aircraft at 06 00 hours. As Hara later admitted: “It did not prove to be a fortunate decision”. At 07 36 hours one of the aircraft reported sighting an aircraft carrier and a cruiser at the eastern edge of the search sector, and Hara, accepting this evaluation, closed distance and ordered an all-out bombing and torpedo attack. In fact, the vessels which had been sighted were the luckless Neosho and her escorting destroyer, USS Sims.

Fifteen high-level bombers attacked, but failed to hit their targets. However, about noon, a further attack by 36 dive-bombers sealed the fate of the destroyer. Three 500 pound bombs hit the Sims, of which two exploded in her engine room. The ship buckled and sank stern first within a few minutes, with the loss of three hundred and seventy nine lives. Meanwhile, 20 dive-bombers had turned their attention to Neosho, scoring seven direct hits and causing blazing gasoline to flow along her decks. Although some hands took the order to 'make preparations to abandon ship and stand by' as a signal to jump over the side, the Neosho was in fact to drift in a westerly direction until 11th May, when one hundred and twenty three men were taken off by the destroyer Henley and the oiler was scuttled. But the sacrifice of these two ships was not vain, for if Hara's planes had not been drawn off in this way, the Japanese might have found and attacked Fletcher.

Five precious hours were lost in this uncharacteristically inept affair and Takagi lost his chance to locate and engage TF 17. In a belated attempt to save the day, the Japanese launched another strike at the Yorktown, but an error in calculating the target's position led the strike astray. On their way back they were hammered by the Yorktown's Combat Air Patrol (CAP), which shot down 9 aircraft for the loss of 2 of their own. The survivors then lost their way and four even tried to land on Yorktown in error, until the carriers opened fire.

The Japanese had wasted almost 20 percent of their strength, all for an oiler and a destroyer, and still the American carriers had not been located. The Japanese carriers turned northwards, while the Yorktown turned southeast to clear a patch of bad weather which was hindering flying, but during the night the Japanese reversed their course so as to be able to engage shortly after dawn. They kept in touch with the Yorktown's movements and were able to launch a dawn search next morning, with a strike to follow as soon as the target was located.

Rear-Admiral Fletcher handed over tactical command to Rear-Admiral Fitch in the Lexington, who ordered a big search to be flown off at 06 25 hours. At about 08 00 hours a Japanese plane radioed a sighting report which was intercepted by the Americans and passed to Fitch, but almost immediately this disquieting news was followed by a report that the Japanese carriers had been found. A combined strike of 84 aircraft was put up by the Lexington and Saratoga, but 30 minutes earlier the Japanese had launched their own strike of 69 aircraft. The world's first carrier-versus-carrier battle had started.

The two American carriers' strikes were about 20 minutes apart and so Yorktown struck first with 9 torpedo bombers and 24 dive-bombers. The torpedo strike was a failure, but two bombs hit Shokaku, one forward which started an avgas (aviation fuel) fire, and one aft which wrecked the engine repair workshop. Lexington's group made a navigation error and so failed to find the target; after nearly an hour's search only4 dive-bombers and 11 torpedo-bombers had sufficient fuel left for an attack when they sighted the smoke from the burning Shokaku. Only one bomb hit, on the starboard side of the bridge, which caused little damage and 5 aircraft were shot down by the Japanese.

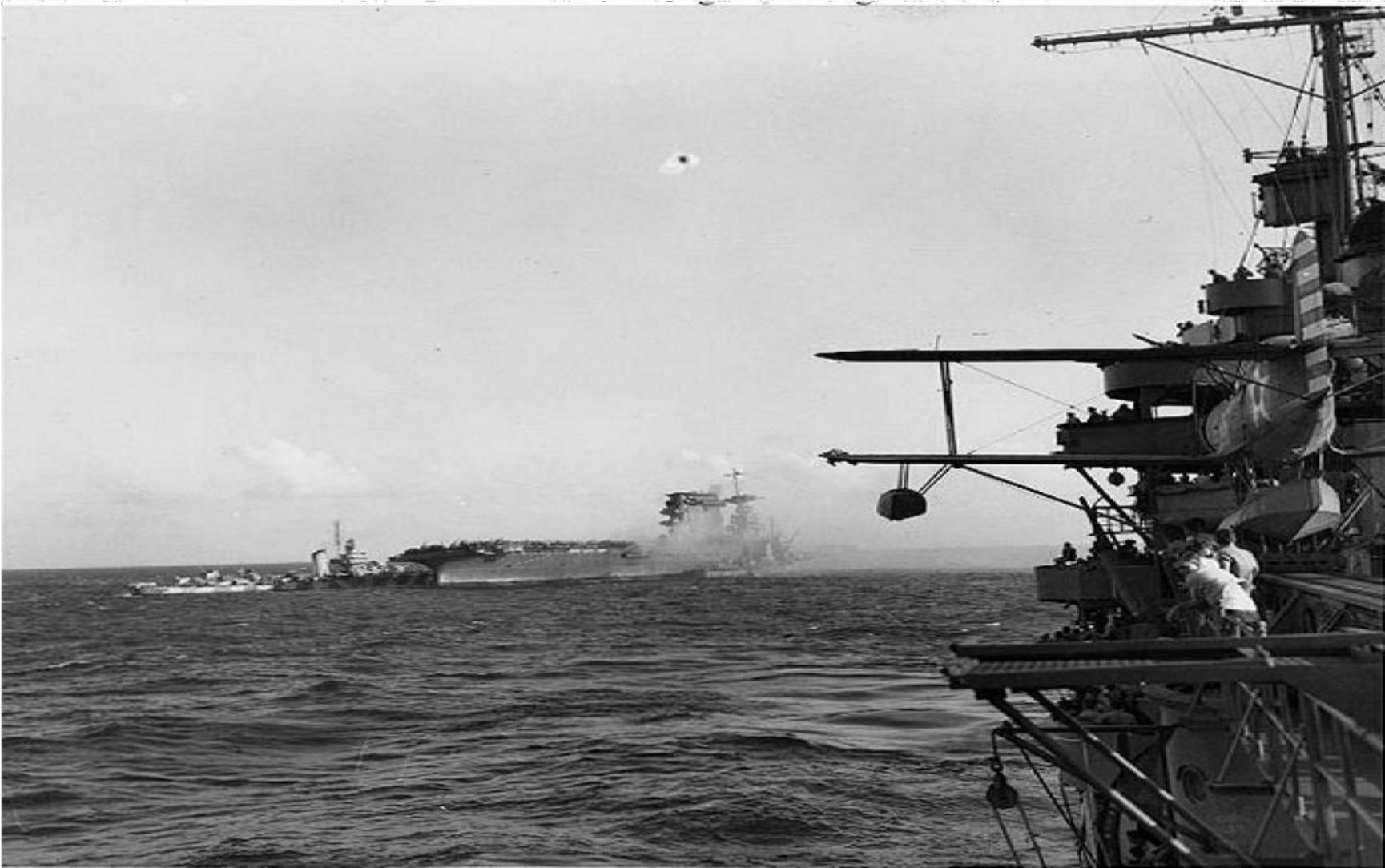

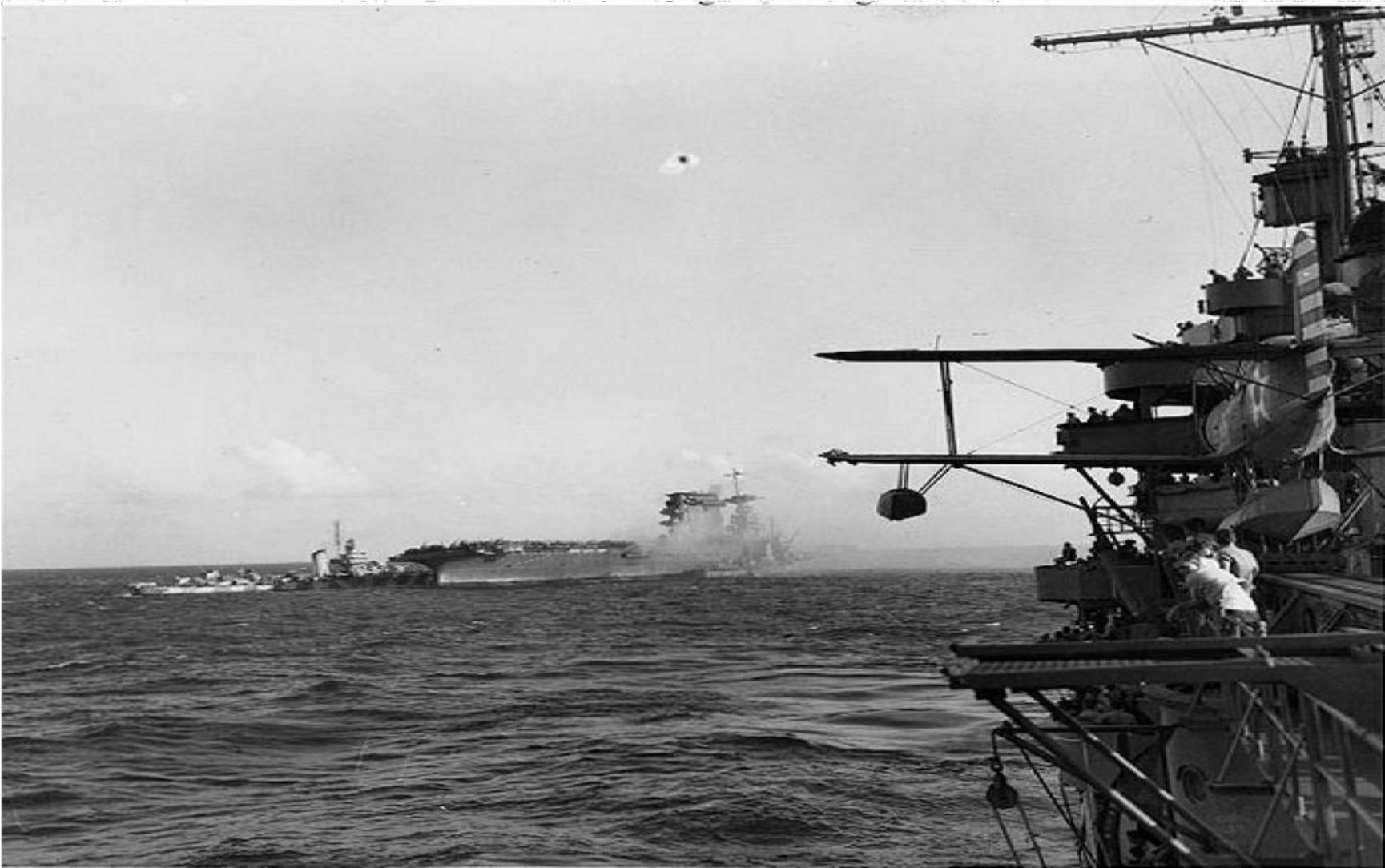

The Japanese attack began at 11 18 hours, with 51 bombers and 18 fighters operatin