CHAPTER TEN

BATTLE of MIDWAY

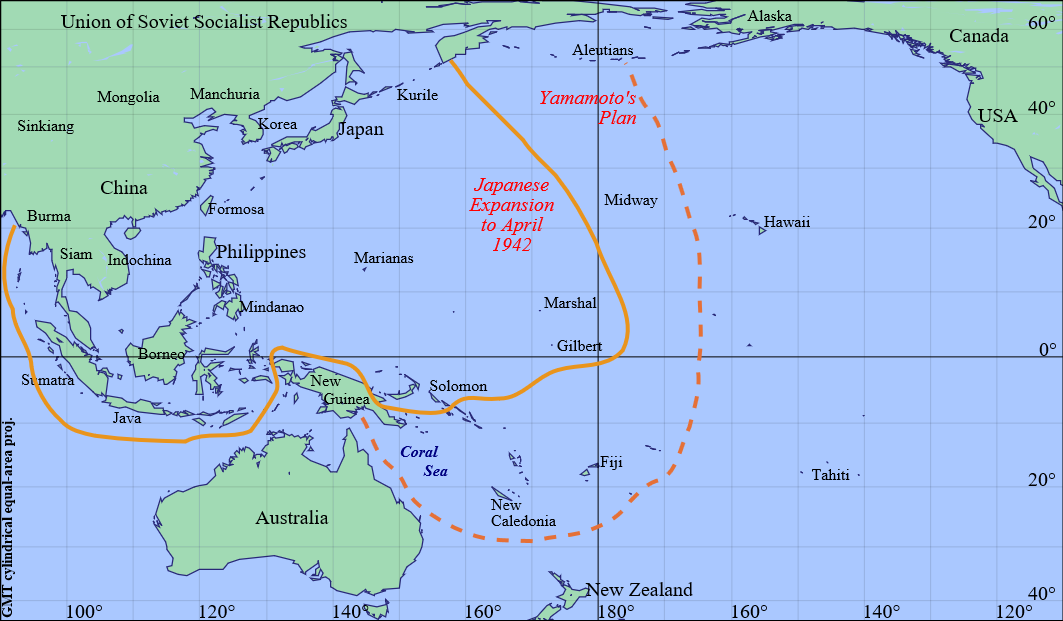

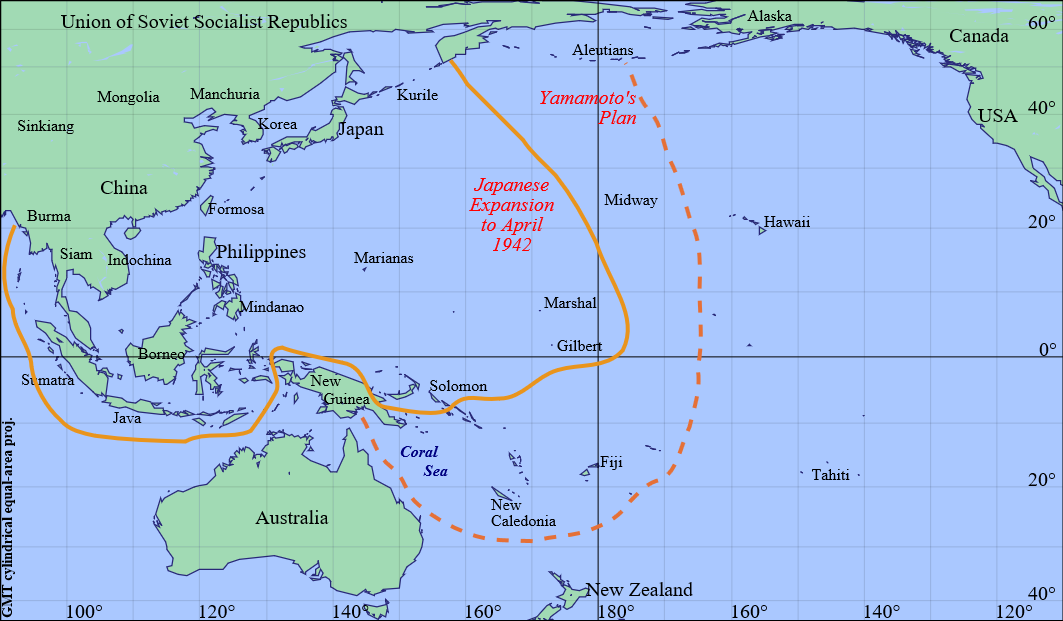

On Wednesday 20th May, 1942, Allied listening stations around the Pacific picked up a lengthy coded radio signal from Admiral Yamamoto to his fleet. The message was relayed to Pearl Harbour and deciphered by the US Combat Intelligence Unit ('Hypo'). It revealed that the Imperial Japanese Navy was about to mount a powerful attack on the tiny mid-Pacific atoll of Midway, 1 100 miles north-west of Pearl Harbour. This was to coincide with a diversionary attack on the Aleutians, far to the north. Soon, using other intercepted messages, 'Hypo' intelligence officers were able to add dates and times to the places: Dutch Harbour in the Aleutians would be hit on June 3rd, Midway the next day.

How was it possible for the Americans to pinpoint Midway as the main objective? It was the culmination of a remarkable intelligence exercise. 'Hypo' had warned early in the year that a strike somewhere in the Hawaiian Islands was on the cards. On May 12th, four days after the Battle of the Coral Sea, they discovered the Japanese code name of the target: 'AF'. But where was 'AF'? The evidence pointed to Midway, but it was not conclusive.

An officer at 'Hypo', Captain Jasper Holmes, then suggested a way to check. The US air base on Midway was ordered to send an uncoded radio signal that the island was having trouble with its water distillation plant, Soon afterwards the Japanese were signalling that 'AF' had water problems. The Americans now knew for certain where the Japanese blow would fall.

The C-in-C Pacific, Admiral Chester Nimitz, was now aware, from deciphering of enemy signals, that the Japanese fleet was intent on throwing down a challenge, which, in spite of local American inferiority, had to be accepted. The proceeding Battle of Midway ranks among one of the truly decisive battles in history. In one massive five minute action, Japan’s overwhelming superiority in naval air strength in the vast Pacific Ocean was wiped out.

More than half the Japanese fleet-carrier strength, together with their irreplaceable, elite, highly trained and experienced aircrews were eliminated; resulting in the Japanese naval air arm being thrown on the defensive from then on. The early run of victories which Yamamoto had predicted had come to a premature end. Now a period of stalemate was to begin, during which American industrial muscle would overpower their Pacific enemy, which Yamamoto had also foreseen.

On 26th May 1942, the aircraft-carriers Enterprise and Hornet of Task Force (TF) 16 had steamed into Pearl Harbour, to set about, in haste, the various operations of refuelling and replenishing. The next day the Yorktown with blackened sides and twisted decks, bearing the scars of her bomb-damage in the Coral Sea battle, berthed in the dry dock. Yorktown had been so badly damaged that the Japanese believed it was sunk, and thus, they would face only two American carriers.

One thousand four hundred workmen swarmed aboard to begin repairs. Under normal circumstances, two months of work would have been necessary for maintenance. But, with the knowledge that the Japanese were heading for Midway, Nimitz ordered the Navy Yard to make emergency repairs in the utmost speed. Work was to continue, night and day, without ceasing, until the ship was at least temporarily battle worthy. The men of the dockyards completed this in less than 46 hours.

Therefore, on 28th May, TF 16, consisting of the Enterprise flying the flag of Rear Admiral Raymond Spruance with the Hornet, six cruisers, nine destroyers, and two replenishment tankers following, left Pearl Harbour. The next day the Yorktown, as TF 17 left harbour under the command of Rear Admiral Fletcher, accompanied by two cruisers and five destroyers headed to rendezvous with TF 16, three hundred and fifty miles north-east of Midway.

The Americans had been forced to make changes in their command structure. Rear-Admiral Fletcher continued to fly his flag in the Yorktown as commander of TF 17, but Halsey had fallen ill and the command of TF 16 passed to Rear-Admiral Spruance. Although not an aviator Spruance had commanded the screen under Halsey and backed up by Halsey's highly competent air staff he was to prove an able task force commander.

The main objective of the Japanese was to extend Japan's newly conquered eastern sea frontier so that sufficient warning might be obtained of any threatened naval air attack on the homeland. Doubts on the wisdom of the Japanese plan had been voiced in various quarters; but Yamamoto, the dynamic C-in-C of the Combined Fleet, had fiercely advocated it. He had always been certain that only by destroying the American fleet could Japan gain the breathing space required to consolidate her conquests. A belief which had inspired the attack on Pearl Harbor. Yamamoto, believed rightly, that an attack on Midway was a challenge that Nimitz could not ignore. It would bring out the US Pacific Carrier Fleet where Yamamoto, with superior strength, would be waiting to bring it to action.

While the Japanese leaders, after a string of dazzling victories, were debating where they should strike next, their minds had been made up for them. Lt. Colonel James Doolittle's raid on Tokyo with B-25 bombers, on 18th April, had put the sacred person of the Emperor in danger. The mortified generals and admirals decided that every gap in Japan's defensive perimeter must be plugged and Midway was such a gap.

Between 25/27th May, the Japanese Northern Force sailed from Honshu for the attack on the Aleutians under the command of Rear Admiral Kakuta. This was expected to induce Nimitz to send at least part of his fleet racing north. But Nimitz, being forewarned, refused to rise to the bait.

Yamamoto believed that the capture of Midway would pose a serious threat to Pearl Harbour. His opposite number, Admiral Nimitz, would then have to try to retake Midway. Waiting for him would be the powerful Japanese fleet. Yamamoto would spring the trap, and achieve what had eluded him at Pearl Harbour; the destruction of American naval power in the Pacific. With the western seaboard of the USA now at the mercy of the Japanese, President Roosevelt would have no alternative but to sue for peace, or so the argument ran.

Yamamoto committed almost the entire Japanese fleet to his plan; some 160 warships, including eight aircraft carriers, and more than 400 carrier based aircraft, compared with the three carriers, about 70 other warships and 233 carrier aircraft (plus another 115 planes stationed on Midway) at Nimitz's disposal. But Yamamoto separated his forces into five main groups, all too far apart to support or reinforce each other.

The original plan had called for the inclusion of the Zuikaku and Shokaku in Nagumo's force. But, both had suffered damage in the Coral Sea battle and could not be repaired in time to take part. Both carriers had also lost many experienced aircrews and few replacements were available.

Leading the attack was the First Carrier Striking Force under Vice Admiral Nagumo, with four carriers; Akagi, Kaga, Hiryu and Soryu with 225 aircraft on board. They were to deliver a powerful preliminary bombardment of Midway before the five thousand strong invasion force landed from 12 transport vessels. Apart from its immediate escort, the invasion force was to be protected by two support groups, each 50 to 75 miles away. Over 600 miles astern of Nagumo was the main Japanese battle fleet with seven battleships, led by Yamamoto's colossal new flagship, the 70 000 tonne Yamato. These, Yamamoto planned, would finish off the US fleet after the carriers had inflicted the decisive damage.

A worse feature of the Japanese organisation, was the fact that they were so loosely co-ordinated and quite unable to support each other within the narrow time limits available. Thus everything was decided on 4th June, between Vice Admiral Nagumo's four aircraft-carriers and Rear Admirals Fletcher and Spruance's three. On the decisive day the battleships, cruisers, and destroyers never fired a shot and the 41planes on board the light aircraft-carriers Zuiho and Hosho took no part in the action.

The Midway strike had all the hallmarks of Japanese planning. It was over complex, made unjustified assumptions about how the enemy would react, and failed to concentrate force. Even so, it might well have worked had American intelligence failed.

This is not to say that Yamamoto's logic was completely at fault; the bombardment of Midway on 4th June, and the planned assault on the atoll next day would compel Nimitz to send his carriers out to sea, calculated by the Japanese to take place on 7th or 8th June. This would give Nagumo time to recover his freedom of action and the Japanese C-in-C to draw in his scattered forces. To leave nothing to chance, on 2nd June, two squadrons of submarines were to station themselves along all the routes the Americans might take on their way to assist Midway. Logical this might have been, but the vital defect was that it depended on the enemy doing exactly what is expected. If he is astute enough to do something different, in this case to have fast carriers on the spot, the operation is thrown into confusion. But Yamamoto had no idea that the enemy was reading his mail.

The Japanese plan was, as their naval strategic plans customarily were, calling for exact timing at the crucial moment; and it involved, also typically, the offering of a decoy or diversion to lure the enemy into dividing his force or expending his strength on a minor objective.

Yamamoto, with the Main Body, was to take up a central position from which he could proceed to annihilate whatever enemy force Nimitz sent out. To ensure that the dispatch of any such American force should not go undetected, Pearl Harbour was to be reconnoitred between 31st May and 3rd June, by 2 Japanese flying-boats, refuelled from a submarine. This was a further precaution to the two cordons of submarines already in position by 2nd June, with a third cordon farther north towards the Aleutians.

Yamamoto's plan had two fatal defects. For all his enthusiasm for naval aviation, he had not yet appreciated that the day of the monstrous capital ship as the queen of battles had passed in favour of the aircraft-carrier which could deliver its blows at a range 30 times greater than that of the biggest guns. The role of the battleship was now as an escort to the vulnerable aircraft-carriers, supplying the defensive anti-aircraft gun power the latter lacked. Nagumo's force was supported only by two battleships and three cruisers. Had Yamamoto's Main Body kept company with it, the events that were to follow might have been very different.

Far more fatal to Yamamoto's plan, however, was his assumption that it was shrouded from the enemy, and that only when news reached the Americans that Midway was being attacked would they order their carriers out of Pearl Harbour. Thus long before the scheduled flying-boat reconnaissance, and before the scouting submarines had reached their stations, Spruance and Fletcher, unknown to the Japanese, were beyond the patrol lines and poised waiting for the Japanese at Midway.

As a result the Japanese had no news from that source and, to make matters worse, this was the last chance that the Japanese had of finding out the strength of the Americans and they remained convinced that only two carriers were operational in the Pacific. The most important piece of information which eluded the Japanese was the fact that the Yorktown was not only afloat but in fighting trim.

Nimitz also had a squadron of battleships under his command, but he had no illusions that, with their insufficient speed to keep up with the aircraft-carriers, their great guns could not play any useful part in the events to follow. They were therefore relegated to defensive duties on the American west coast. For the next few days the Japanese Combined Fleet advanced eastwards according to schedule in its widespread, multipronged formation. Everywhere a buoyant feeling of confidence showed itself, generated by the memories of the unbroken succession of Japanese victories since the beginning of the war. In the 1st Carrier Striking Force, so recently returned home after its meteoric career of destruction from Pearl Harbour, through the East Indies, and on to Ceylon without the loss of a ship. The 'Victory Disease' as it was subsequently to be called by the Japanese themselves, was particularly prevalent.

Spruance and Fletcher had meanwhile rendezvoused during 2nd June, and Fletcher assumed command of the two task forces, though they continued to manoeuvre as separate units. The sea was calm under a blue sky split up by towering cumulus clouds. The scouting aircraft, flown off during the following day in perfect visibility, sighted nothing, and Fletcher was able to feel confident that the approaching enemy was unaware of his presence north-east of Midway. Indeed, neither Yamamoto nor Nagumo, pressing forward blindly through rain and fog, gave serious thought to such an apparently remote possibility.

On 3rd June at 09 00 hours, when the first enemy sighting reports reached them, Fletcher and Spruance were in a good position to act against the enemy when he attacked the atoll. On leaving Pearl Harbour they had received the following warning from Cincpac in anticipation of the enemy's superior strength: "You will be governed by the principle of calculated risk, which you shall interpret to mean the avoidance of exposure of your force to attack by superior enemy forces without good prospect of inflicting, as a result of such exposure, greater damage on the enemy".

That Fletcher and Spruance were able to carry out these orders successfully was 'due primarily to their skilful exploitation of intelligence, which enabled them to turn the element of surprise against the Japanese. Even so, on 1st June the Japanese admiral's flagship intercepted 180 messages from Hawaii; 72 of which were classified ‘urgent’. This sudden intensification of radio traffic, as well as the great increase in aerial reconnaissance, could mean that the enemy forces were now at sea or about to set sail. Should Nagumo, sailing more than 600 miles ahead of the main force, be alerted? This would mean breaking the sacrosanct radio silence and Yamamoto could not bring himself to.do it, although the Americans seemed to be aware that Midway was targeted. In such a situation, it was a case of ‘effectiveness comes before camouflage’.

Far to the north on 3rd June, dawn broke grey and misty over the Aleutians, Kikuta's two aircraftcarriers launched the first of two strike waves to wreak destruction among the installations and fuel tanks of Dutch Harbour. A further attack was delivered the following day, and the virtually unprotected Aleutians were occupied by the Japanese. But as Nimitz refused to let any of his forces be drawn into the skirmish, this part of Yamamoto's plan failed to have much impact on the great drama being enacted farther south.

The opening scenes of this enactment took place on 3rd June, when a scouting Catalina flying boat some 700 miles west of Midway sighted a large body of ships, steaming in two long lines with a numerous screen in arrowhead formation, which was taken to be the Japanese main fleet. The sighting report brought nine army B-17 bombers from Midway, which delivered three high-level bombing attacks and claimed to have hit two battleships or heavy cruisers and two transports. But the enemy was in reality the Midway Occupation Force of transports and tankers, and no hits were scored on them until four Catalina’s from Midway discovered them again in bright moonlight in the early hours of 4th June, and succeeded in torpedoing a tanker. Damage was slight, however, and the tanker remained in formation.

More than 800 miles away to the east, Fletcher intercepted the reports of these encounters but from his detailed knowledge of the enemy's plan was able to identify the Occupation Force. Nagumo’s carriers he knew, were much closer, some 400 miles to the west of him, approaching their flying-off position from the north-west. During the night, therefore, Task Forces 16 and17 steamed south-west to a position 200 miles north of Midway which would place them at dawn within scouting range of the unsuspecting enemy. The scene was now set for what was to be a great decisive battle.

The last hour of darkness before sunrise on 4th June, saw the familiar activity in both the carrier forces of ranging-up aircraft on the flight-deck for dawn operations. Aboard the Yorktown, whose turn it was to mount the first scouting flight of the day, there were Dauntless scout dive-bombers, ten of which were launched at 04 30 hours for a search, while waiting for news from the scouting flying boats from Midway.

Reconnaissance aircraft were dispatched at the same moment from Nagumo’s force. One each from the Akagi and Kaga; two seaplanes each from the cruisers Tone, and Chikuma were to search to a depth 300 miles to the east and south. The main activity in Nagumo's carriers, however, was the preparation of a striking force to attack Midway, 36 'Kate’ torpedo-bombers each carrying a 1 770 pound bomb, 36 'Val' dive-bombers each with a single 550 pound bomb, and 36 Zero fighters as escort. Led by Lieutenant Tomonaga, this formidable force also took off at 04 30 hours.

By 04 45 hours all these aircraft were on their way, with one notable exception. In the cruiser Tone, one of the catapults had given trouble, and it was not until 05 00 hours that her second seaplane got away. This apparently minor dislocation of the schedule was to have catastrophic consequences. Meanwhile, the carrier lifts were already hoisting up on deck an equally powerful second wave; but under the bellies of the 'Kates' were hung torpedoes, for these aircraft were to be ready to attack any enemy naval force which might be discovered by the scouts.

The major difference was that the Americans knew they were looking for carriers; the Japanese were not even certain that any American carriers could be in the vicinity. Admiral Nagumo launched 108 aircraft for the first softening up of Midway's defences, but he cautiously held back Kaga's air group in case any American ships were sighted. Fletcher took much the same precaution by launching only 10 Dauntlesses from the Yorktown to search to the north, just to make sure that the Japanese task force had not turned his flank.

The lull in proceedings which followed the dawn fly-off from both carrier forces was broken with dramatic suddenness. At 05 20 hours, aboard Nagumo's flagship Akagi, the alarm was sounded. An enemy flying boat on reconnaissance had been sighted. Zeros roared off the deck in pursuit. A deadly game of hideand-seek among the clouds developed. But the American naval fliers evaded their hunters. At 05 34 hours, Fletcher's radio office received the message 'Enemy carriers in sight', followed by another reporting many enemy aircraft heading for Midway; finally, at 06 03 hours, details were received of the position and composition of Nagumo's force, 200 miles south-west of the Yorktown. The time for action had arrived.

The Yorktown's scouting aircraft were at once recalled and while she waited to gather them in, Fletcher ordered Spruance to proceed 'south-westerly and attack enemy carriers when definitely located'. Enterprise and Hornet with their screening cruisers and destroyers turned away, increasing to 25 knots, while hooters blared for 'General Quarters' and aircrews manned their planes to warm-up ready for take-off. Meanwhile, 240 miles to the south, Midway was preparing to meet the impending attack.

Radar had picked up the approaching aerial swarm at 05 53 hours and 7 minutes later every available aircraft on the island had taken off. Bombers and flying-boats were ordered to keep clear, but Marine Corps fighters in two groups clawed their way upwards, and at 06 16 hours swooped in to the attack. But of the 26 planes, all but 6 were obsolescent Brewster Buffaloes, hopelessly outclassed by the highly manoeuvrable Zeros. Though they took their toll of Japanese bombers, they were in turn overwhelmed, 17 being shot down and 7 others damaged beyond repair. The survivors of the Japanese squadrons pressed on to drop their bombs on power plants, seaplane hangars, and oil tanks.

At the same time as the Marine fighters, 10 torpedo-bombers had also taken off from Midway, 6 of the new Grumman Avengers and 4 Army Marauders. At 07 10 hours they located and attacked the Japanese carriers; but with no fighter protection against the many Zeros sent up against them, half of them were shot down before they could reach a launching position. Those which broke through, armed with the slow and unreliable torpedoes which had earned Japanese contempt in the Coral Sea battle, failed to score any hits; greeted with a storm of gunfire, only one Avenger and two Marauders escaped to crash-land on Midway. The Japanese had damaged the US base, but its bombers were safely out of the way and the airfield was still usable. Tomonaga signalled to Nagumo that a second attack was needed to knock it out.

This put Nagumo in a quandary. He knew neither where the US fleet was nor how many ships it had. But, as ordered by Yamamoto, he had held back his best aircrews, their planes armed with torpedoes and other anti-ship weapons, in case the US carriers arrived sooner than expected. Yet his search planes had spotted no enemy ships and he needed to finish the job at Midway. Just then Midway based bombers started attacking his ships. They did no damage, but they made up Nagumo's mind for him, and changed the course of the battle. The Japanese commander ordered his second wave torpedo bombers to be rearmed with bombs for another attack on Midway.

As no inkling of any enemy surface forces in the vicinity had yet come to him, he made the first of a train of fatal decisions. At 07 15 hours he ordered the second wave of aircraft to stand by to attack Midway. The 'Kate' bombers, concentrated in the Akagi and Kaga, had to be struck down into the hangars to have their torpedoes replaced by bombs. Ground crews swarmed round to move them one by one to the lifts which took them below where mechanics set feverishly to work to make the exchange. It could not be a quick operation, however, and it had not been half completed when, at 07 28 hours, came a message which threw Nagumo into an agony of indecision.

One of Nagumo's search planes spotted 10 US warships some 210 miles north-east of the Japanese carriers. This plane had taken off half an hour late that morning, delayed when the launching catapult on the heavy cruiser Tone jammed. Had it taken off on time, it might well have spotted the US ships half an hour earlier. Fated to be the one in whose search sector the American fleet was to be found; sent back the signal. 'Have sighted ten ships, apparently enemy, bearing 010 degrees, 240 miles away from Midway: Course 150 degrees,' speed more than 20 knots’. For the next quarter of an hour Nagumo waited with mounting impatience for a further signal giving the composition of the enemy force.

Only if it included carriers was it any immediate menace at its range of 200 miles, but in that case it was vital to get a strike launched against it at once. At 07 45 hours Nagumo ordered the re-arming of the 'Kates' to be suspended and all aircraft to prepare for an attack on ships, and two minutes later he signalled to the search plane: 'Ascertain ship types and maintain contact.' The response was a signal of 07 58 hours reporting only a change of the enemy's course; but 12 minutes later came the report: 'Enemy ships are 5 cruisers and 5 destroyers.

This message was received with heartfelt relief by Nagumo and his staff; for at this moment his force came under attack first by 16 Marine Corps dive-bombers from Midway, followed by 15 Flying Fortresses, bombing from 20 000 feet, and finally 11 Marine Corps Vindicator scout-bombers. Every available Zero was sent aloft to deal with them, and not a single hit was scored by the bombers. But now, should Nagumo decide to launch an air strike, it would lack escort fighters until the Zeros had been recovered, refuelled, and re-armed. While the air attacks were in progress, further alarms occupied the attention of the battleship and cruiser screen when the US submarine Nautilus, one of 12 covering Midway fired a torpedo at a battleship at 08 25 hours. But neither this nor the massive depth-charge attacks in retaliation were effective; and in the midst of the noise and confusion of the air attacks, at 08 20 hours, Nagumo received the message he dreaded to hear: 'Enemy force accompanied by what appears to be a carrier’.

The luckless Japanese admiral's dilemma, however, had been disastrously resolved for him by the return of the survivors of Tomonaga's Midway strike at 08 30 hours. With some damaged and all short of fuel, their recovery was urgent; and rejecting the advice of his subordinate carrier squadron commander RearAdmiral Yamaguchi, in the Hiryu to launch his strike force, Nagumo issued the order to strike below all aircraft on deck and land the returning aircraft. By the time this was completed, it was 09 18 hours.

Refuelling, re-arming, and ranging-up a striking force on all four carriers began at once, the force consisting of 36 'Val' dive-bombers and 54 'Kates', now again armed with torpedoes, with an escort of as many Zeros as could be spared from defensive patrol over the carriers. Thus it was at a carrier force's most vulnerable moment that, from his screening ships to the south, Nagumo received the report of an approaching swarm of aircraft. The earlier catapult defect in the Tone; the inefficient scouting of its aircraft's crew; Nagumo's own vacillation (perhaps induced by the confusion caused by the otherwise ineffective air attacks from Midway); but above all the fatal assumption that the Midway attack would be over long before any enemy aircraft-carriers could arrive in the area, all had combined to plunge Nagumo into a catastrophic situation. The pride and vainglory of the victorious carrier force had just one more hour to run.

When Task Force 16 had turned to the south-west, leaving the Yorktown to recover her reconnaissance aircraft, Nagumo's carriers were still too far away for Spruance's aircraft to reach him and return; and if the Japanese continued to steer towards Midway, it would be nearly 09 00 hours before Spruance could launch his strike. When calculations showed that Nagumo would probably be occupied recovering his aircraft at about that time, however, Spruance had decided to accept the consequences of an earlier launching in order to catch him off balance. Every serviceable aircraft in his two carriers, with the exception of the fighters required for defensive patrol, were to be included, involving a double launching, taking a full hour to complete, during which the first aircraft off would have to orbit and wait, eating up precious fuel.

It was just 07 02 hours when the first of the 67 Dauntless dive-bombers, 29 Devastator torpedo bombers, and 20 Wildcat fighters, which formed Task Force 16's striking force, flew off. The torpedo squadrons had not yet taken the air when the sight of the Tone's float plane, circling warily on the horizon, told Spruance that he could not afford to wait for his striking force to form up before dispatching them. The Enterprise's dive-bombers led by Lieutenant-Commander McClusky, which had been the first to take off, were ordered to lead on without waiting for the torpedo-bombers or for the fighter escort whose primary task must be to protect the slow, lumbering Devastators. McClusky steered to intercept Nagumo's force which was assumed to be steering south-east towards Midway. The remainder of the air groups followed at intervals, the dive-bombers and fighters up at 19 000 feet, the torpedo-bombers skimming low over the sea.

This distance between them, in which layers of broken cloud made maintenance of contact difficult, had calamitous consequences. The fighters from the Enterprise, led by Lieutenant Gray, took station above but did not make contact with Lieutenant Commander Waldron's torpedo squadron from the Hornet, leaving the Enterprise's torpedo squadron, led by Lieutenant-Commander Lindsey; unescorted. Hornet's fighters never achieved contact with Waldron, and flew instead in company with their dive-bombers. Thus Task Force 16's air strike advanced in four separate, independent groups, McClusky's dive-bombers, the Hornet's dive-bombers and fighters, and the two torpedo squadrons.

All steered initially for the estimated position of Nagumo, assuming he had maintained his south-easterly course for Midway. In fact, at 09 18 hours, having recovered Tomonaga's Midway striking force, he had altered course to north-east to close the distance between him and the enemy while his projected strike was being ranged up on deck. When the four air groups from TF 16 found nothing at the expected point of interception, they had various courses of action to choose between. The Hornet's dive-bombers decided to search south-easterly where, of course, they found nothing. As fuel ran low, some of the bombers returned to the carrier, others made for Midway to refuel. The fighters were not so lucky: one by one they were forced to ditch as their engines spluttered and died.

The two torpedo squadrons, on the other hand, low down over the water, sighted smoke on the northern horizon and, turning towards it, were rewarded with the sight of the Japanese carriers shortly after 09 30 hours. Though bereft of fighter protection, both promptly headed in to the attack. Neither Waldron nor Lindsey had any doubts of the suicidal nature of the task ahead of them. The former, in his last message to his squadron, had written: “My greatest hope is that we encounter a favourable tactical situation, but if we don't, and the worst comes to the worst, I want each of us to do his utmost to destroy the enemy. If there is only one plane left to make a final run in, I want that man to go in and get a hit. May God be with us all”.

His hopes for a favourable tactical situation were doomed. Fifty or more Zeros concentrated on his formation long before they reached a launching position. High overhead, Lieutenant Gray, leading the Enterprise's fighter squadron, wa