CHAPTER ONE

THE BATTLE OF THE RIVER PLATE

On December 1939 a Royal Navy Squadron consisting of the Heavy Cruiser Exeter, and the Light Cruisers Ajax and Achilles intercepted the German Pocket Battleship Graf Spee. A classic naval engagement then took place off the South American coast near Uruguay that became renowned as the Battle of the River Plate. During the battle the Graf Spee put the Exeter out of action, seriously damaging both the Ajax, and the Achilles.

The Graf Spee, however, also received a number of hits and her captain thought it necessary to take refuge in Montevideo for repairs. He was convinced that stronger British naval forces were close at hand and being unable to complete the repairs within the allotted time, the Graf Spee was blown up by her crew.

This spectacular feat of naval arms, won primarily by psychological means, held the world’s attention. It also earned worldwide admiration for the Royal Navy and gave a lift to British morale. The destruction, of such a formidable warship that the Germans claimed to be invincible, by three outgunned British cruisers, set off a great outburst of rejoicing in Britain. It was the first victory of the war and Churchill summed up the mood of the people when he exulted; “In a cold winter it warmed the very cockles of the nation’s heart”.

Why did this naval battle mean so much to the people of the British Empire? Particularly, as it virtually paled into insignificance when compared to later epic sea battles, such as the sinking of the Bismarck; the Fleet Air Arm victory at Taranto that crippled the Italian navy; Pearl Harbor that brought the United States into the war; Midway, that broke the back of the Japanese naval air strike force; and Leyte Gulf that destroyed the Japanese surface fleet to establish the United States as an incontestable naval power.

All of these operations were of far greater importance than the Battle of the River Plate.

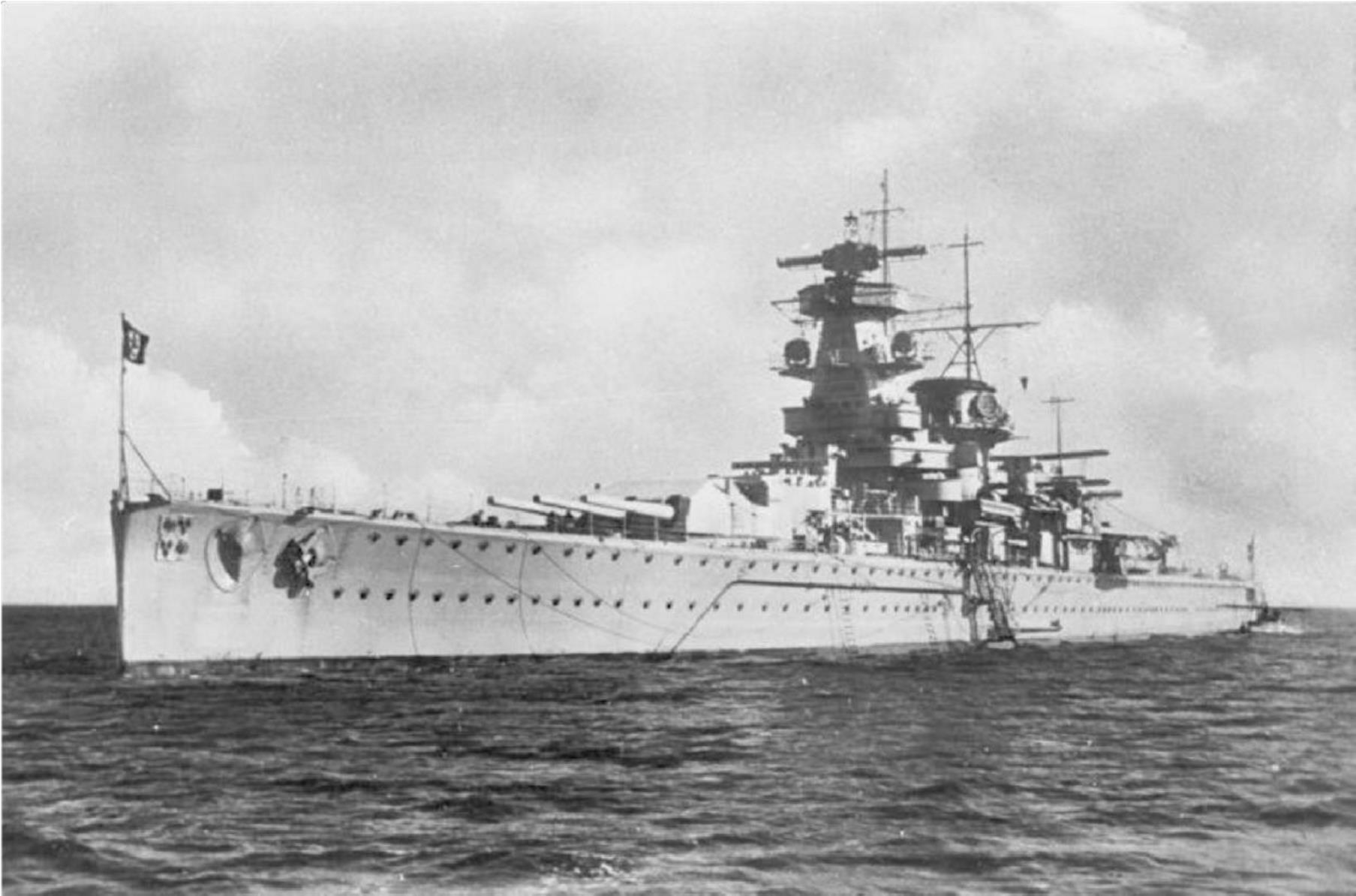

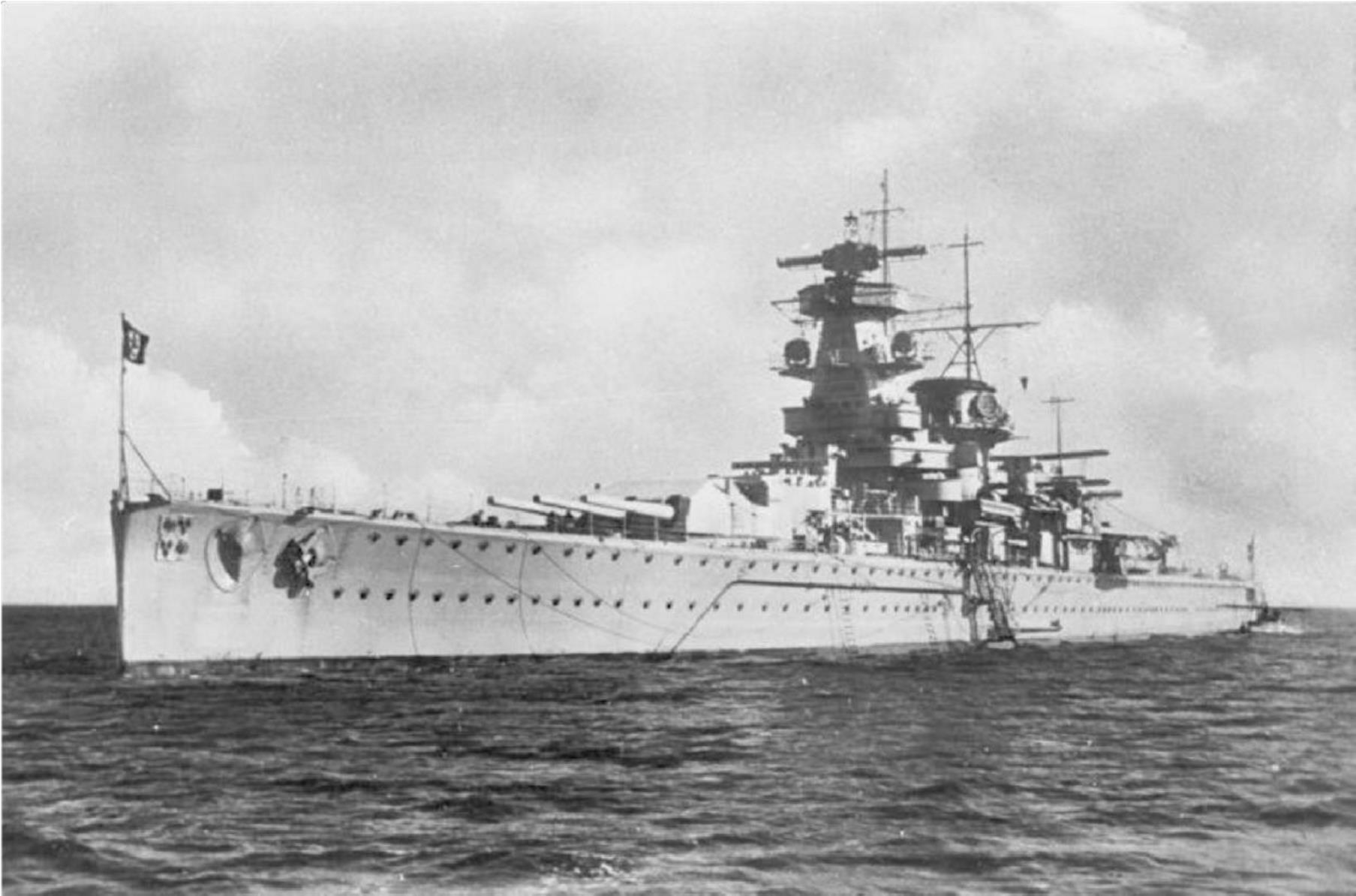

There are several factors that need to be considered; at the end of World War One, under the Versailles Treaty, Germany was only permitted to build warships up to a certain size. Battleships in particular, were restricted to a mere 10 000 tons. However, due to German ingenuity and technological skills, there emerged a completely new warship design and this unique concept was dubbed the ‘Pocket Battleship’. These brilliantly engineered warships had six 11 inch guns plus eight 5.9 inch guns and were capable of 26 knots. They were slightly larger than the Washington Treaty conventional cruisers but much smaller than contemporary battleships. These diesel powered warships had a wide radius of action that allowed them to cruise over the oceans without relying on land bases.

Three of them were built; besides the Graf Spee, there was the Deutschland and the Admiral Scheer, each with a complement of nearly one thousand two hundred men. The Deutschland was later renamed Lutzow as Hitler did not wish any ship named after the Fatherland to be sunk. These ships were expected to play a crucial role in the ‘Battle of the Atlantic’. A campaign that would totally dominate British naval policy throughout the war; and, on which everything ultimately depended. The sacrifice was horrific; 2 800 allied merchant vessels, and almost 200 warships were sunk, culminating in the loss of forty thousand Allied seamen and 15 million tons of shipping. Focusing specifically on the Graf Spee; the saga opened when she slipped out of port in August 1939, just before the outbreak of hostilities and secretly sailed to the South American shipping routes. Graf Spee’s supply ship the Altmark also sailed to a predetermined rendezvous position in the Atlantic. The German naval command hoped to achieve immediate and crushing results through the operation of their pocket battleships.

On the declaration of war on 3rd September 1939, Graf Spee camouflaged her appearance and successfully deceived merchantmen into thinking that she was a French heavy cruiser. She also proved to be most elusive, and her speed and unpredictability enabled her to sink nine merchant ships totalling 50 000 tons in three months. Some of Graf Spee’s victims did, however, manage to transmit distress signals, thus alerting the admiralty that a pocket battleship was at large. As a result all available Allied battleships, battle cruisers and cruisers were formed into powerful hunting groups to search the entire Atlantic oceans from Greenland to the Falklands. This was of course, part of German strategy; that is to disperse the Royal Navy’s superior strength.

With this intention, the Graf Spee headed for the Indian Ocean, and on 3rd November 1939, she steamed 400 miles south of Cape Town. Well out of reach of air reconnaissance; and thrust up the South African coast line to the Mozambique Channel. Consideration was given to using Graf Spee’s Arado spotter aircraft to bomb Durban’s oil storage tanks, but this was considered too risky and abandoned. Shortly after arriving in the Mozambique Channel, the Graf Spee intercepted and sank the British oil tanker Africa Shell.

Consequently, a senior officer stationed at Durban, on receiving a distress signal from Africa Shell radioed a warning of the presence of a German surface raider in the Indian Ocean. This electrified the British

Admiralty, resulting in several Royal Navy hunting ships to be redirected to this area. Graf Spee’s Captain Langsdorff picked up the warning signal and concluded that his mission in the Indian Ocean had succeeded. He therefore, returned to the South Atlantic for a final campaign before triumphantly returning to Germany for Christmas and an engine overhaul.

Meantime, Commodore Henry Harwood, commander of the Royal Navy cruiser squadron ‘Force G’ in the South Atlantic had shrewdly calculated the reason behind the Graf Spee’s foray into the Indian Ocean. He estimated she would soon be lured back to the South Atlantic and the rich shipping harvest at the River Plate. He therefore, patrolled this region with the heavy cruiser Exeter and the light cruisers Ajax and Achilles. He was aware that the Graf Spee had the advantage of knowing that all warships sighted were enemy ships and due to her taller look-out mast and aircraft would 13th December when the Graf Spee lookout spotted warship masts on the horizon.

Langsdorff knew they had to be enemy ships, but due to his spotter plane being out of action, due to a cracked cylinder block he mistakenly assumed they were probably light vessels escorting a convoy. He soon realised his mistake when the heavy cruiser Exeter accompanied by two light cruisers were identified. Nevertheless, he reasoned that he would be unable to shake off the faster British ships and decided that action was unavoidable. But, in committing the Graf Spee to attack Langsdorff was effectively ignoring strict orders not to engage enemy warships. He was specifically forbidden to expose his ship to the risk of a naval battle. In total disregard of instructions, Langsdorff ordered battle stations and full speed ahead towards his adversaries.

Commodore Harwood aboard his flag ship Ajax ordered Captain Bell on the Exeter to close and investigate the smoke on the horizon. The pocket battleship was quickly identified; at long last the Royal Navy had found its elusive enemy and the ‘Battle of the River Plate’ was about to commence. Ajax, Achilles and Exeter prepared to engage Germany's fabled pocket battleship in deadly combat and more than one hundred brave young sailors would lose their lives.

In terms of weight of guns and armour the odds were certainly in German favour, but the British had the advantage of numbers and manoeuvrability. The Graf Spee’s gunners were now forced to choose between three objectives while the British could concentrate on only one target. Graf Spee’s 11 inch guns had a range of 17 miles, the 6 inch guns of Ajax and Achilles, 10 miles and Exeter's 8 inch guns, 15 miles. On the face of it Langsdorff had little to fear, and could engage effectively out of range of the three British cruisers. He was confident that his much more powerful main armament would make short work of the Royal Navy's lighter ships.

On the other hand and regardless of the odds, Harwood had a centuries old naval tradition to uphold, and immediately deployed his ships into their pre-arranged positions with the objective of splitting the enemy’s fire. He likewise ordered action stations and full speed ahead; the heavy cruiser Exeter to engage on starboard and the two light cruisers on the port side. The German pocket battleship prepared to simultaneously engage the two smaller ships with her secondary guns and trained her main armament guns on the Exeter. Visibility was near perfect when Graf Spee closed rapidly and opened fire. In deciding to go for a quick kill, Langsdorff misjudged and this cost him his principal advantage of not only outranging but also out-gunning his adversaries. But, it was too late for that now.

The Graf Spee concentrated on the Exeter and soon straddled her to wreck ‘B’ turret. The next salvo hit Exeter amidships and everyone on the bridge except Captain Bell was badly injured or killed. It is difficult to imagine what it must be like aboard a ship during battle. There is little to compare to the hell and brutality of a sea-battle; men are trapped in combating warships that literally throw tons of high explosives at each other, and when hit, a deafening explosion sends lethal particles of shrapnel within the ship's interior; causing unfortunate men to be cut down instantly in death or mutilation. The fire, fumes and flooding in darkened confined spaces must bring terror to the survivors.

Returning to the action, as Graf Spee closed in to finish off the Exeter, her sister ships, Ajax and Achilles raced forward with all guns blazing, forcing the German pocket battleship to switch her heavy armament to them. Thus allowing Captain Bell to take the badly listing Exeter away just as her last gun was put out of action. She had been reduced to a floating inferno and forced to limp southwards to the Falklands.

Most of Ajax's guns were soon out of action, and under cover of a smoke screen fired torpedoes at her foe. Graf Spee turned away to avoid the torpedoes and at this point inexplicably seemed to lose heart and decided to break off the 90-minute action. It is difficult to imagine why a much heavier armed and formidable ship should run from two damaged light cruisers instead of eliminating them. The difference was possibly due to the British commander knowing exactly what he intended to do and the German commander not.

In deciding to attack, Langsdorff should have finished off the Exeter quickly before the two light cruisers could take up position. And by frequently changing from one target to the other, the Graf Spee’s rate of fire was enormously slowed up. Possibly it was Harwood’s aggressive tactics that confused Langsdorff. This, combined with his indecisiveness over which target to engage with the main armament, the Exeter to starboard or the Achilles and Ajax to port cost the famed pocket battle ship the battle.

Casualties on the British side, however, were heavier than on the German. The crippled Exeter had lost sixty four of her officers and men. The badly damaged Ajax had seven dead and there were many wounded on the Achilles. Graf Spee’s damage initially appeared superficial, but inspection revealed that the galleys were wrecked, and some secondary guns had been put out of action. She was also holed near the waterline, and although she had taken 20 hits and lost thirty six of her crew, her fighting ability was unimpaired.

Langsdorff now had immediate and crucial decisions to make; he ultimately came to the conclusion that his ship was not sufficiently seaworthy to reach Germany. Therefore, he decided to make for the shelter of the nearest neutral port of Montevideo to patch up the damage. Captain Langsdorff had been wounded twice during the action and knocked unconscious; perhaps the temporary concussion he had suffered affected his judgment in reaching this decision.

Several further exchanges of fire were made between Graf Spee and the two damaged British ships trailing her until she docked at Montevideo. On arrival, Captain Langsdorff greeted Herr Otto Langmann, the German Minister with a smart naval salute. The Minister replying with the Nazi version ruefully commented, “Gentlemen I wish I could say welcome to Uruguay, but you have made a serious error in bringing your ship here”. The reason was, although Uruguay was a neutral country; her sympathies lay with the Allies. Therefore, the international law that states belligerent warships are only entitled to stay in a neutral harbour for 24 hours was imposed. The Uruguayans later extended the deadline to 72 hours but refused any further extension. Strenuous political negotiation failed to gain further time and Graf Spee was ordered to leave neutral waters by 20 00 hours on the following Sunday 17th December. .

The German authorities actually requested two weeks to repair Graf Spee’s damage in the hope that this would provide sufficient time for U Boats to reach the scene and assist the pocket battleship. Ironically, the British also wanted the departure delayed, to provide time for heavier Royal Navy units to arrive. Meanwhile the crew of the Graf Spee was allowed to disembark in full uniform for the burial of the thirty six fellow crew members that had been killed during the battle. With the exception of Captain Langsdorff, everyone at the service, including the priests, saluted in Nazi style.

During the next few days intense British diplomatic manoeuvres combined with false and misleading reports led Langsdorff to conclude that he was trapped and internment or scuttling were the only choices open to him. He was mistakenly informed that Royal Navy heavy ships including the Battle Cruiser Renown and the Aircraft Carrier Ark Royal were waiting for him.

The Graf Spee had used up more than half her ammunition during the battle. He reasoned, therefore, that a similar naval battle would have been beyond Graf Spee’s fighting capacity. He deemed the situation hopeless and erroneously thinking that a powerful British fleet was off the coast, communicated his position to the German High Command and put forward three alternatives for evaluation:

-

Internment in Montevideo after the 72-hour deadline had lapsed.

-

Fight out to open sea, or;

-

Scuttle the ship.

German High Command negated any idea of internment and left the final choice to Captain Langsdorff between fighting out to sea and scuttling the ship with the proviso that if he chose to scuttle, then he must ensure the effective destruction of his ship. Captain Langsdorff addressed his crew informing them that he was not prepared to engage in a senseless battle that would only serve to sacrifice their lives in a death or glory attempt to break out to open sea. He further explained that if he chose to ignore the deadline, his ship would certainly be interned and classified information may fall into British hands.

Consequently, on 17th December, the Graf Spee set off slowly from Montevideo harbour toward her fate with battle ensigns flying. The Royal Navy ships reinforced by the heavy cruiser Cumberland that had steamed at record speed from the Falklands closed up for action stations. Over a quarter million people had gathered on the waterfront eager, to witness a great naval battle.

The international spotlight for the previous four dramatic days had been cantered on Montevideo. Front pages around the world were reporting the full story and an American radio broadcast, live from Montevideo, filled the international airwaves with updates of the developments. The British cruiser squadron and millions of anxious listeners expected the pocket battleship to come out with guns blazing. Naval tradition demanded she battle her way out or go down fighting. Tension mounted as Graf Spee made for the territorial limit.

The hundreds of thousands watching the spectacle and the world wide listeners to the running commentaries from Montevideo were shocked when it was sensationally broadcast that a huge explosion had engulfed the Graf Spee. Langsdorff had deduced there was no alternative against reportedly overwhelming odds but to scuttle. Thus bringing this fine ship, that had sunk 50 000 tons of merchant shipping, and tied down half the British fleet for three months, to an ignominious end.

Langsdorff then took his crew on tugs to a German merchant ship and disembarked in Buenos Aires. They were interned and remained there for the rest of the war; many of them stayed on after the war

It later emerged that Langsdorff had been dissuaded by his officers from personally setting off the explosives and going down with his ship. However, now that he considered he had done all he could possibly do for the welfare of his crew and not wishing any dishonour of the flag, he decided he could not survive his ship. Three days later Captain Langsdorff dressed in full uniform, wrapped himself in the imperial German flag that he had fought under at Jutland, and shot himself. German and British seamen plus local dignitaries paid their last respects to Captain Langsdorff when he was buried with full military honours.

The aftermath of this classic naval engagement and some of the foremost personalities involved, deserve closer examination.

What kind of a person was Captain Langsdorff, bearing in mind that his significant role in the dramatic saga of the Graf Spee has remained controversial and obscure? Hans Wilhelm Langsdorff was the 18year-old son of a Düsseldorf judge when he joined the Imperial German Navy in 1912. He saw front line action at the Battle of Jutland in 1916 and served the remainder of the war commanding minesweepers. After the war he served as a Staff Officer before taking command of Graf Spee in 1938.

Langsdorff was actually considered by many to be an officer and a gentleman of the old school. After his death, several noted historians considered him to have been a ‘first class person’. Describing Langsdorff as a highly trained, intelligent naval officer who achieved his wartime objectives while maintaining personal codes of honour and decency; faithfully fulfilling his duties. They further state; ‘In World War Two, mankind sank to abysmal levels of inhumanity. But, in December 1939, German Captain Hans Langsdorff gave the world a matchless example of personal integrity and human compassion’.

So, it would appear that at the time of the Battle of the River Plate, he was thought to be an exceptional naval commander and a man of the highest character. This may be borne out by the fact that he had dispatched Allied merchant shipping without inflicting the loss of a single life, even though this certainly put his ship and crew at risk. Of the sixty two prisoners from captured merchant vessels, on board of the Graf Spee, not one got harmed, not even during the battle.

But in Nazi Germany the media information about the battle was suppressed and Graf Spee's commander never received any credit for his efforts. In fact, the country he fought and died for demeaned his actions. Hitler was most displeased with Langsdorff and chastised him for not fighting to the finish and going down with his ship. Immediately after the loss of Graf Spee, Admiral Raeder, the German Navy Chief, criticised Captain Langsdorff, claiming that he had lost Graf Spee when he ignored standing orders, that is not to seek battle with enemy warships.

Raeder ordered there would be no repeat of Graf Spee’s scuttling stating: “In future a German warship and her crew are to fight with all their strength until they are victorious or go down with their flag flying”. It would appear that this may have been a political standpoint because privately Raeder sent a letter to Langsdorff’s mother, praising her son as an excellent officer, remarking favourably on his noble character and stated that he fought like a gentleman and died like a gentleman.

These are all the accolades that were heaped on Captain Langsdorff. But in probing a little deeper, the obvious question is, did he commit suicide to show that he had not acted out of cowardice but to save his men, or, was it to avoid court martial for disobeying orders? Why did he not use his Arado aircraft, or on the assumption they were unserviceable, use land based air reconnaissance to ascertain actual British naval strength off the coast? It is fine to be an officer and a gentleman, and it is OK to be mister nice guy and be popular with your men; but the priority is to get the job done.

Churchill said after Dunkirk “wars are not won by evacuation”. In this case then, scuttling your ship and blowing your head off, regardless of the excuses, do not win naval battles. When has a Royal Navy commander ever scuttled his ship to avoid contact with perceived superior enemy forces? The opposite in fact has occurred on many occasions. An example is the destroyer Glowworm attempting to ram the German heavy cruiser Hipper at Norway. There is also the armed merchantman Jervis Bay taking on the pocket battleship Admiral Scheer in an effort to protect an Atlantic convoy. After all, war is war, and you provide your enemy with victory on a plate by scuttling your ship and committing suicide. The objective is to inflict as much damage as possible on your enemy not to self-destruct.

To quote General Patton; “Nobody ever won a war by dying for his country, the idea is to make the enemy die for his”.

It has also been suggested that Langsdorff was ordered by Hitler to commit suicide, but there is no evidence to support this. Furthermore, Captain Langsdorff did not display good tactical awareness and appeared to be devoid of any battle plan, being reactive not proactive. Perhaps he had no stomach for confrontation.

As the war progressed, the pocket battleships, despite the enormous range provided by their diesel engines failed to live up to expectations. In 1942 for example, in comparison to the Allied losses inflicted by the U Boats, the entire German surface fleet sank the equivalent of what the U Boats achieved in just one month.

What happened to the Royal Navy ships that seen action at the River Plate? The Exeter, after surviving the 11-inch guns of the Graf Spee later joined Allied operations at the Dutch East Indies and was sunk by the Japanese at the Battle of Java Sea in 1942. The Ajax served the remainder of the war in the Mediterranean. The Achilles also survived the war. The Achilles saw action at Normandy, destroying a German pillbox; the only Allied warship to achieve this.

Commodore Harwood was knighted and promoted to Rear Admiral. He was only the second naval commander since Admiral Horatio Nelson to be knighted in battle. He died in 1950.

Both British and German participants in the Battle of the River Plate have met several times in friendly reunions since the war. Veterans still celebrate the comradeship that evolved from the River Plate Battle.

For example, a Canadian town in Ontario carries the name ‘Ajax’ in honour of the British cruiser, and has named many streets as a living memorial to the officers and men who manned the British ships. In 1999, a proposal to add Captain Langsdorff's name to the programme was unanimously supported by the veterans. In Germany and Argentina to this day, annual reunions of Graf Spee's surviving crew members honour the memory of Captain Langsdorff and this loyalty to the Captain has not waned in over sixty years despite continued military criticism of his decisions.

Another irony is that the Battle of the River Plate was the opening British naval victory of World War Two and it took place almost exactly 25 years after the opening British naval victory of World War One in August 1914. The Battle of the Falkland Islands was fought between the same enemies, in the same coastal region. The German commander, Admiral Graf Spee perished with his sons in this engagement with the Royal Navy.

As a postscript, many British merchant crewmen that had been captured by the Graf Spee were later transferred to her supply ship Altmark. Whilst en route to prisoner of war camps in Germany, the Altmark was intercepted in Norwegian territorial waters, by the Royal Navy destroyer Cossack. On the direct orders of the First Lord of the Admiralty, Winston Churchill, the Royal Navy boarded the Altmark and freed the prisoners.

Prior to the Altmark incident in February 1940, Hitler had shown little enthusiasm for the invasion of Norway. However, the incident infuriated and convinced him that Britain was no longer prepared to respect Norwegian neutrality. He subsequently ordered an invasion to be mounted on a top priority basis. A direct result of this campaign was that Churchill replaced Chamberlain as Prime Minister, thus ensuring that Britain would remain in the war until final victory. So, the Battle of the River Plate cannot be viewed in isolation; it did have a profound effect on later developments.

The faint remains of Graf Spee can still be seen in the shallow water and mud where it was scuttled in 1939.