IV

THE BOMBER

'THE CALL OF THE BUGLE.'

The Bugles of England were blowing o'er the sea,

As they had called a thousand years—calling now for me.

They woke me from my dreaming in the dawning of the day,

The Bugles of England—and how could I stay!

The Banners of England unfurled across the sea,

Floating out upon the wind, were beckoning to me.

Storm-rent and battle-torn, smoke-stained and grey:

The Banners of England—and how could I stay!

O England, I heard the cry of those who died for thee,

Sounding like an organ voice across the winter sea;

They lived and died for England, and gladly went their way:

England, O England—how could I stay!

PTE. J. D. BURNS, A.I.F.

(Killed in action, Gallipoli.)

Son of Rev. ---- Burns, late of Bairnsdale, Victoria.

IV

THE BOMBER

We had a treasure in our battalion—a sergeant who knew all about bombs. He liked them, and knew exactly how to treat them. Of course we could not keep such a man in the battalion. He was manifestly called to the vocation of Instructor for Bombing Schools.

They will never make a general of him—he is too valuable in his present capacity. Besides, his grammar and pronunciation are not equal to such a strain. The more lucid his explanations are, the looser is his control of the aspirate; although that is nothing in these days, for I heard a member of the British Parliament speaking the other day, and he---- But that is another story!

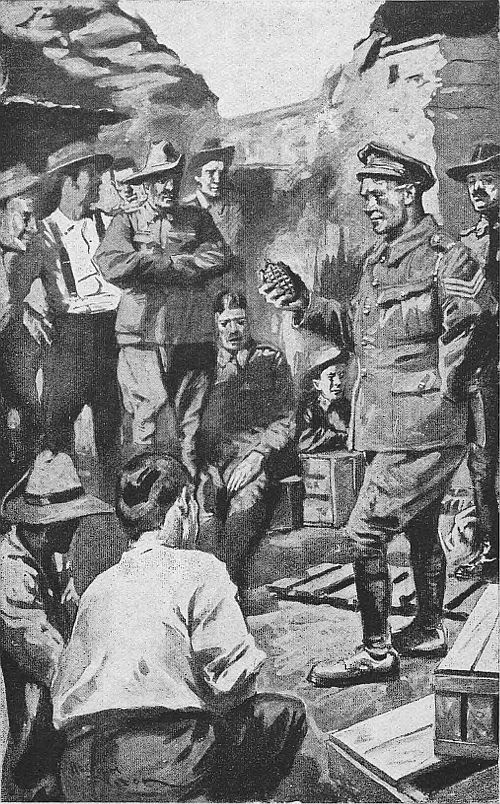

'Bombs is all right if you treat them properly. They will never do no 'arm to you if you don't monkey with them. They are gentle and 'armless things to them as is wise to them,' he would say, addressing his group of humble disciples. 'Gather round and I'll learn you about bombs.' And what time he toyed with the vicious missile the 'class' would gather somewhat fearfully around him.

'When you remove this 'ere pin you release the spring which causes the charge to explode the bomb in the time that you count five—so.' He removes the pin and proceeds to deliberately count, 'One, two, three'; now his disciples begin to melt away, 'four'--'Oh, you needn't worry, five, there ain't no charge in this one. It's empty for experimental purposes.'

He has a wonderful command of hard, technical words, only equalled by his disregard of the proper pronunciation of simple words.

"Gather round, and I'll learn you about bombs."

Now with reassured courage the class gather round again, and he takes up a 'live' bomb.

'As you count three, you hurl the bomb, not with a jerk, but with a smooth round arm bowling motion. So—one, two, three,' and he hurls the bomb clear into a trench forty yards away. It explodes with a loud detonation, smashing up the trench, and he resumes his lecture.

'Although you 'ave removed the pin, you can still keep your bomb right, by pressing the spring until you are ready for action, so you can 'ave a bomb in your 'and just ready for throwing as you go up a German trench. You've got to do it just right, so that Fritz has no time to pick up your bomb and throw it back at you.

'You can 'ave faith in your bombs now. It's not like them there Gallipoli days, when we 'ad to fire jam-tin bombs made on the premises. They was filled with Turkish bullets and all sorts of things, but they couldn't be relied on to do the same thing every time. Did you ever 'ear of Lieutenant Forshaw, V.C., down Cape Hellis way? He hurled jam-tin bombs for forty-two hours at Johnny Turk. He 'ad to light them with his cigarette.

'Not been used to smoking cigarettes, 'im 'aving been brought up as a schoolmaster, the smoking did 'im a lot of 'arm, for which reason the King made 'im a V.C. Lucky fellow, I call 'im. Many's the time I've been short of a fag.'

At once quite a number of the sergeant's pupils present fags, and having made a selection and put a few in his pocket for future use, the sergeant proceeds:

'There's another man I want to tell you about—Captain Shout, V.C., of the 1st Battalion. 'E was throwing bombs at such close range at the Turks that 'e had to have three lit at once for 'im, and 'e fired them just so as they would explode among the enemy. 'E kept this up a long time, and 'eld the enemy up, but one burst too near 'im, and after some time, he died of 'is wounds. A great loss to the A.I.F., believe me. You needn't worry about such-like 'appenings now; only one in two thousand of our Mills' grenade goes wrong, and with the odd one you've got your sporting chance.

'Now, what about bombs that land close to you, sometimes thrown by the enemy, and sometimes by accident, our own, when a man 'its the side of the trench? Don't be too scared. Even then bombs is 'armless properly treated. Get behind a traverse if there is one. If not, then you render the live bomb 'armless. Gather round. I'll show you.'

Sitting on a chair, he took a bomb, and, after counting three, threw it on the ground, not a great way off. The men scatter for all they are worth; but the sergeant, having thrown an overcoat over the bomb, calmly resumes his seat. Crash! goes the bomb at the fifth second. The coat rises with the bomb, the fragments drop harmlessly around, and the coat is not much worse.

'Now then, let that learn you to throw sand-bags, blankets, your own overcoat or some such thing over a bomb, and ten to one no 'arm will follow.

'Did you ever hear of Mulga Bill at Quinn's Post? A bomb dropped in the trench amongst them, and 'e promptly put a sand-bag from the parapet on top of it. To make sure, 'e sat on top of the sand-bag. When it exploded 'e went up with the bag a little way. 'E came down all right and none the worse. But 'e was narked--annoyed, to find his chums laughing at 'im. "What are yer laughing at?" 'e said. "I did that to save you fellows, but I'll never do it again."

'That's where Mulga Bill was wrong. He done right, except sitting on top of it. That was an extra act—a sort of curtain-raiser at the wrong end of the play.

'Let that learn you not to put 'ard substances on a live bomb. It don't take kindly to pressure. I'll show you. Gather round.'

The instructor then proceeds to throw another bomb. As, counting three, he throws the bomb down, he proceeds quickly to put a sheet of corrugated iron on it.

'Now,' he cries, 'run like hell!'--and he showed them the example.

The bomb, exploding, sends fragments, throws the torn iron all around, and the men have learnt another strange lesson in regard to the behaviour of bombs.

Notwithstanding the confident handling of bombs by this expert, I am privately of opinion that men should beware of 'the familiarity which breeds contempt' in the matter of bombs.

There was a man in our Brigade who had just returned from a bombing school with his head stuffed full of all sorts of knowledge about the manufacture and use of bombs. He had a small collection of them, and one morning in the shadow of the Calvary at the cross-roads-at Fleurbaix, having an audience, he held forth on his new subject, illustrating his remarks by fiddling with a small screw-driver at a bomb which he professed to know all about. Suddenly it exploded, wounding him sadly. 'A little learning' had for the moment 'made him mad.'

To get back to our Bombing School. After the instructor's talks, the men in turn would hurl bombs from one trench to another, until they were no longer 'bomb-shy.' As a matter of fact, a good bomber is just as good a 'life' in the army as any other expert. Indeed, a man may lose his life through the absence of a bomb or the knowledge of how to use it.

In the words of our instructor, 'The cure for the bombing craze is--"A hair of the dog that bit you."'

The Germans are good bombers, and when, in their counter-attack, they come down a trench throwing bombs, the only way is to bomb them back and out again.

He used to say, 'The Boches began this blooming bombing business,' only his adjectives were sometimes profane. 'What we have to do is to give them a fair sickening of it. Bomb their Zeppelins, bomb their submarines, bomb their dug-outs'--then, in one final outburst, he would say, 'Bomb the Boches; and if you don't believe what I say, ask the Chaplain.'

If they ask me, how can I contradict him?

Our 'bomber' often surprised us, even to alarm. But the biggest surprise he ever gave us was when he had been granted ten days' (well deserved) leave in 'Blighty,' he turned up again in six. Wondering, the men, who envied him his leave, inquired why he had returned before his leave was up.

'I was very lonely in London,' he replied simply. 'I like to be with my pals.’