CHAPTER VIII

IN THE HOUSE OF PADRE MARJAN—LULASH GIVES A WORD OF HONOR AND DISCUSSES MARRIAGE—THE STOLEN DAUGHTER OF SHALA.

Padre Marjan sat with us, but did not eat, as it was a fast day. An apparently endless succession of dishes—soup, lamb, omelettes, pork chops, chicken—was brought in by Cheremi and served by Rexh in his red fez. Poor little Rexh! He ate nothing but a bit of corn bread; he said the pork chops had been broiled in the fireplace, and he feared that some of the fat had spattered into the cooking pots. He was not sure, but he feared so, and he thought it safer not to eat anything prepared in them.

The lamb’s head, skinned but otherwise intact, was served separately, boiled, and the delicacy of the meal was its brains, which we got at by cutting through the skull. When the chicken came, Cheremi presented it with awe in his eyes, and after we had eaten he whispered behind his hand to Perolli. In the kitchen, he said, they were talking of the chicken; it was not of Padre Marjan’s raising, but it had been hatched and brought up in the village, and they were sure that its breastbone would foretell the immediate future of Thethis. Would we let him have it?

Perolli took up the thin bone and very carefully cleaned it of every clinging bit of flesh. Then, with an apology to Padre Marjan, he held it up to the light from the window. Through the translucent bone the marrow, clouded with clotted blood, showed clearly, and Perolli read it with serious eyes, pointing out to us its meaning. There was a clot that meant a battle, a battle to the north, and there was a widening red line running from a dark spot; the signs were clear. The government would grow more powerful, and there would be war to the north, war with the Serbs.

He gave the bone to Cheremi, who tiptoed toward the kitchen with it. I strained my ears to hear how it was received; I thought that the portent of strong government might make the people think it unwise to hand Perolli over to the Serbs; they must know that in any case his death would be avenged by soldiers from Tirana. But would it, since he was traveling “on a vacation”? Governments do not usually back up their secret-service men who fail on the job. There was no sound from the kitchen, and we entertained Padre Marjan by showing him how, in America, we use the wishbone to foretell a part of the future. But any wishbone will do that for us, while in Albania only the breastbone of a hen that has lived all her life in the family will foretell that family’s future.

Outside, it continued to rain, if that state of the air when it is surely half water can be called rain. We were glad to get back to the kitchen fire. The chiefs and older men of the village did not return, but many women and children came in to talk to the strangers, and it was evident that the padre’s kitchen was the village club-house; they were all at home and happy there. The padre himself washed the dishes and swept the floor with a pine bough, chatting with them all as he did so; one saw, in the atmosphere of intimacy and democracy and respect around him what the Church used to be to the people long ago.

Then he set pans of water to heating for our baths, and when they were warm he lighted the way with a candle to his bedroom, which he had loaned to us. Another large, bare room with wooden unpainted walls, a bedstead of rough boards with a mattress laid on them, and sheets and pillow cases of red-and-white-plaided cotton, hand woven; in one corner an office desk, and on the wall beside the bed a rosary.

At midnight Perolli and Padre Marjan retired to the cold, wet living room, to roll themselves in blankets and sleep on the floor. We three girls sat shivering on the mattress and wished we knew what the chiefs were deciding.

But, oh! it was good to take off the clothes, so many times soaked with rain, in which we had walked and climbed and slept for three days and nights. And forks may be idle luxuries, but there is no question that a thin mattress filled with straw and laid on raised boards is one of the greatest comforts in life!

We were awakened in the damp chill of a watery gray dawn, and with surprise found ourselves on its unfamiliar softness, in the bleak room of unpainted boards. Padre Marjan was knocking at the door. In a moment he entered, barefooted, in his long brown robe girded with cord, and, going to the incongruous office desk, he carefully unlocked a lower drawer and took out a box of soap. There were twenty small cakes of soap in the box. He took out one, carefully, put the box back in the drawer, locked it.

He had been followed by a small boy, a very serious child, and visibly nervous. About eleven years old, he wore the long, tight, black-braided white trousers, colored sash, and woolly, fringed short black jacket of his people, but they were all soaking wet and very old, mended and mended again until hardly any of the original fabric was left. His bare feet were blue with cold, and so were his bare arms, for the Scanderbeg jacket has no sleeves, and he did not wear a shirt. He stood very straight, and swallowed hard, keeping his face impassive.

Padre Marjan turned to him, holding the cake of soap. He spoke earnestly and at some little length. He then presented the cake of soap to the child, who bent a knee to receive it, and kissed the padre’s hand and then the soap. An impressive little ceremonial, which we witnessed, wide eyed, from the mattress where we sat huddled among the blankets. Rain was still sluicing against the windows, so that the water on them was surely as thick as the glass.

We looked inquiringly at Frances, who understood Albanian. Her eyes shone, she was so excited. “It’s a school prize!” she said, and, listening, “He’s the best scholar in school; already he can read and write. Isn’t it splendid!” The boy saluted us gravely; one saw that he had just gone through a profound emotional experience. “Long may you live!” said he, and went out.

Padre Marjan said that the school had been opened ten days before. On the first day there were forty-three pupils, on the second day sixty-two, on the third day ninety-seven. All the tribe was sending its children to live with relatives in Thethis and go to school. No more than ninety-seven could get into the padre’s living room; the others must wait until, with the money Alex and Frances had collected, the schoolhouse could be built. There were no benches or desks, of course; the children stood packed tightly in the cold room, and he taught them by writing with a piece of chalk on the walls. Already this boy could read and write words of one syllable and merited a cake of soap. Padre Marjan, at his own expense, had sent two hundred miles to Tirana for fifty cakes of soap, to be used as prizes. There was, of course, no other soap in the tribe; a more magnificent gift could not have been imagined.

The boy who got the cake of soap walked every morning nine miles over the mountains to reach school at seven o’clock, and at nine, after school, he walked back and took out the goats and spent all day climbing trees and cutting twigs for them to eat.

Padre Marjan said that as soon as he knew the Americans would build the school he had started teaching, and he had written to the government in Tirana and asked if it would help. He brought from the desk the letter he had received in reply. Written by hand, for the poverty-stricken young government had no typewriters, and sent by messenger into the mountains, in six weeks it had reached Thethis, and the padre kept it wrapped in a bit of hand-woven silk. Frances spelled it out; it said that the government would give a hundred kronen a month to pay the teacher. It was signed for the Minister of the Interior by Rrok Perolli.

“My sainted grandmother!” cried Frances. “Where is Perolli?” At that very minute the chiefs might be sending word to the Serbs to come and get him. The chiefs themselves would surely not violate the hospitality of their priest, but the Serbs would have no reverence for it and they were only a few miles away. When we thought what a bargain the chiefs might drive with the Serbs for Perolli it seemed too much to hope that one of them, at least, would not hand him over.

Padre Marjan spoke warmly of Perolli, whom he had so innocently betrayed; he said that he had once seen him at a distance in Scutari, and the village was honored to have him for a guest. While he said this he wrapped the precious letter in its silk and laid it carefully away in the desk. Then he went away, saying that he would send us a fire.

In a few minutes it came, a pile of hot coals in a large iron baking dish. Cheremi set it in the middle of the floor—where, indeed, it made little impression on the damp chill of the room—and went to fetch us cups of Turkish coffee. But we were too anxious to linger over it; we swallowed it hastily and dressed as quickly as possible, talking about what we could do to save Perolli. We thought that perhaps as American citizens we could overawe the Serbs, but none of us really had much hope of it; indeed, we had no right to attempt American protection for a secret-service agent of the Albanian government along the borders of the land held by invading Jugo-Slav armies. Still, we did not know that he was a secret-service agent; we had every right to suppose that he was merely our companion on a vacation trip. It was all very vague, but distressing.

Frances and Alex hurried out to find Perolli, but I sat helpless. No human effort would get my feet into the iron-hard shrunken shoes that had so long been water soaked. What on earth was I to do? Could I go barefooted over the mountains? More immediate question, could I go forth shoeless to inspire terror of America in the breasts of possible Serbs? Ignoble predicament!

While I sat struggling with the obdurate leather the door opened and in came the magnificent figure of Lulash, the chief. He had none of the marks of self-conscious importance that our statesmen have; he was as simple, as graceful, and as unself-conscious as a tiger in his own jungle, and at the moment he struck me with something of the same spellbound, half-admiring terror. He looked as capable of swift, unconcerned killing as the rifle on his back. Behind him came Perolli, betraying the tension of his excitement only by the ease with which he concealed it.

Lulash saluted me as I stared up at him, petrified, from the mattress. “Long may you live!” said he, and, swinging the rifle from his back, he set it against the padre’s desk. Then he sat down on the floor—there were, of course, no chairs in the room—close to the baking dish filled with warm coals. He did not lounge, but sat straight, his legs folded beneath him, and Perolli sat similarly on the other side of the baking dish. Lulash took a silver tobacco box from his sash and slowly rolled a cigarette; Perolli took from his pocket a box of the American variety; they exchanged cigarettes, lighted them by bending close to the red coals, and sat back again, watching each other in silence for some moments.

I put my shoes down stealthily, making not the slightest noise, tucked my feet beneath me, and sat perfectly still. Outside, the rain made a swishing sound; the soft roaring of a thousand waterfalls ran beneath it like an accompaniment. Thin streaks of snow-chilled, wet air came through the many cracks in the board walls and floor; they tore the cigarette smoke into dancing wisps. Wet spread slowly on the walls; the floor was spotted with damp where we had dropped our sodden clothes the night before. The coals in the baking dish were filming over with gray ash.

It was the first time I had ever been present at a diplomatic conference, and that one on which the fate of a nation depended. For if these mountain men did turn Perolli over to the Serbs, getting thereby the favor of the armies that held their cities and grazing lands, I had no doubt that it meant soldiers from Tirana coming up to Thethis, civil war with the northern tribes, and not at all improbably the murdering of the new-born government. Perhaps, indeed, another outbreak in the Balkans, the sore spot of Europe. And I could not understand Albanian!

Lulash spoke first, in short, decisive sentences. I caught the word “Serbs” and the word for “markets.” At the end of each sentence Perolli shook his head sidewise, in the quick gesture that means, “Yes.” Lulash was stating the case; Perolli was in his power; the Serbs wanted Perolli; the Serbs held Thethis’s markets and grazing lands; moreover—for I caught the word “kronen”—there was the probability of reward. To all this Perolli assented. He had not yet spoken.

There was another slight pause, but not for him to break. Lulash was thinking. Then he leaned a little forward, put his hand on his heart, and spoke again. There was not the faintest expression on Perolli’s face; I could not make out what was happening. When Lulash had ceased speaking Perolli smoked for a moment in silence. “You have done well,” he said, then, in Albanian; and to me, “Have you got your fountain pen?”

I got it out of my trousers pocket and gave it to him quickly—too quickly. He was very leisurely about taking it. Then he opened his notebook and wrote in it. Lulash watched the moving pen with a sort of awed fascination. Perolli read aloud the words he had written, closed the notebook, and put it in his pocket. He showed no pleasure of relief, but the very atmosphere of the room had lightened.

Both men leaned back more easily and for the first time seemed to taste their cigarettes. Lulash looked at me; the aquiline profile became a full-face view of the handsome, sensitive, strong face framed in folds of white. What did I look like to those mountain eyes, I wondered, sitting there disheveled among tumbled blankets, a brown sweater bunched around my neck, my riding trousers creased and muddy and dangling their unputteed legs?

“I should be glad to see the women of my tribe wearing American garments,” said Lulash. “Skirts are heavy and cumbersome; trousers are far better.”

Perolli translated.

“Goodness! He thinks all American women wear trousers!” I said. “Well, tell him I thank him; I agree with him; for the mountains trousers are more comfortable. Tell him I am much interested in the women of his tribe and would like to ask him some questions about them. And I’ll die right here if you don’t tell me what’s happened.”

“He will be glad to tell you anything he knows, but no man understands the nature of women, which is like the streams that run under the mountains. Don’t worry; it’s all over.”

“What do you mean? Ask him if he thinks it is a good idea to betroth children before they are born. (What did you write in the notebook?)”

“He says he does not think it a good idea. (I tell you it’s all right.)”

“Oh, thank goodness! Then he does not think the women are happy in their marriages? (But tell me what he was saying to you, won’t you?)”

“He says that as for happiness, his people do not expect happiness in marriage; happiness comes from other things. (I cannot tell you; he would understand the word; I will spell it. He has sworn a b-e-s-a that his whole tribe will be loyal to the Albanian government as long as he lives. Careful! Don’t let him suspect I’m talking about it.)”

Albanians, with their many languages, are used to such conversations. I hope I deceived Lulash; my training in dissimulation has been small. I was rather dizzy.

“From what does their happiness come, then?” said I. (“For Heaven’s sake, what happened to make him do that?”)

“Happiness,” said Lulash, “comes from the skies. It comes from sunshine, and from light and shadow on the mountains, and from green things in the spring. It comes also from rest when one is tired, and from food when one is hungry, and from fire when one is cold. It comes from singing together, and from walking on hard trails and being harder than the rocks; and there is a kind of happiness that comes to a man in battle, but that is a different kind. For us, marriage has nothing to do with happiness.”

Perolli, translating, added, “He did it because the Albanian government has helped the American school here.”

Then for the first time I really looked at Lulash. He had been until then simply a marvelously beautiful animal; a man such as men must have been before cities and machines and office desks brought dull skins and eyes, joy rides, padded shoulders, and crippling collars. Now I perceived that he was also a real person.

He saw beyond immediate gain for himself or his people. He had refused any advantages to be gained by this unexpected dropping into his hands of this man that the Serbs wanted; he lived under the shadow of mountains alive with Serbian troops, his village was filled with Serbian influences, the Tirana government was two hundred miles away, and he knew nothing of it except that it had promised a hundred kronen a month to the mountain school that Alex and Frances had started. Yet he had come, voluntarily, without urging, to swear a besa of loyalty to that government because it had helped the school. And the besa, the word of honor, would hold him, I knew, as the strongest treaties never hold Western governments. I admired that man. I felt a tender sort of pity for him, too, because of his faith in the value of being able to read. After all, what has it done for us? Like most of civilization, it has done little more than create a useless desire that men become slaves to satisfy. It has made us very little kinder, very little less unsympathetic with alien points of view, and no farther from war, poverty, and misery than the Albanians are.

“Then what does marriage mean to the Albanians?” I said, grasping for the thread of the conversation.

Lulash was really puzzled by my idea that marriage and happiness were in some way connected. He was courteous, but there was a little surprise in his voice. “Marriage is a family question,” he said. “One marries because one is old enough to marry, and that is the way the family goes on from generation to generation. You marry in America, do you not? You keep the family alive? How are marriages arranged in America?”

“With us,” I said, “marriage does not have much to do with the family. Young people grow up thinking about themselves. Then, when they are old enough, if they have money enough to live on, and if they meet some one they like and want to marry, they marry. They marry to be happy, because they have found some one they want to live with always. They go away from their families, sometimes very far away, and live in a house by themselves.”

It came over me, while I watched the surprise growing in Lulash’s eyes, how haphazard and egotistic—how shallowly rooted, really—our whole system is. We marry because we want another human being, because—it really comes to that—we want to use that other human being to make happiness for ourselves. For even when one gets happiness by giving, instead of taking, it is still fundamentally a demand, a demand that the other take what is given, and that is sometimes the hardest of all demands to satisfy. Two persons, each demanding that the other be a source of personal happiness to him or her, each demanding, clutching, insisting on that gift from the other—that is the spectacle of American marriage. No wonder it so often ends in a heap of wreckage, out of which maimed human beings struggle through divorce.

“I do not understand what you mean by saying they must have money enough to marry,” said Lulash. “There is always money enough to marry, isn’t there? A man costs the tribe no more married than not married, and if new girls are brought into the tribe by marriage, others are given away in marriage. Even in the poorest tribes marriages never stop.”

“We have another system of owning property in America,” said I. “By that system, often men cannot afford to marry until they are quite old. They are never able to marry as young as you do here. In fact, many persons never marry at all.”

“Because there are not enough women?”

“Oh no! The women work, too, and do not marry. (Goodness! Perolli, tell him it is too difficult to explain.)”

“He thinks,” said Perolli, “that you mean that in your country the young men live like priests and the women like sworn virgins, such as they sometimes have here. He’s very deeply shocked by such an idea. I’ll have to tell him something—what? Either way, he’ll get the idea that Americans are utterly immoral.”

“Well, say that we have—that we have another kind of marriage, that isn’t exactly marriage—say we have concubines. He’ll understand that, from Turkey,” said I, in desperation. And while Perolli endeavored to explain and still uphold the honor of America in the eyes of a profoundly shocked chief of Shala, I tried to devise another way of getting at the subject. For I did want to know what Albanian women felt about being married to men they had never seen, in strange tribes, and I knew they would never tell me through masculine interpreters. Lulash would know.

“But most of the sources of happiness that you mentioned are in the lives of men,” I said. “Are the women happy?”

“No,” said Lulash. “I do not think our women are happy.” He seemed deeply troubled; there were perplexity and anxiety in his dark eyes, and he moved restlessly—which Albanians almost never do—as he sat on the floor by the heap of coals in the baking dish. They had sunk quite into gray ashes; the bleak room was very cold, filled with the ceaseless swishing sound of the rain and of the innumerable waterfalls that poured from the mountains overhead.

“Perhaps I shouldn’t be asking him this? Perhaps he is married to an unhappy woman?” I asked.

“No,” said Perolli. “He is not married; he is the only man in Shala who is not married.”

“Our women have their children; they love their children,” said Lulash. “And they do not quarrel with their husbands. It almost never happens that there are ugly words in a family. But I do not think the women are happy. I do not know whether they would be happier if they chose their own husbands. Girls of the marrying age are not very wise. But I often think, when I see a young girl taken away to the house of some old man, who perhaps is sick and ugly and morose because he must stay all day in the house, that it is a sad thing. For myself, I would like to see the American way tried here. I have said to my people that it is wrong to betroth children before they are born. We do not do it very often, now. Usually they are five or six years old, old enough so that one can see what they will become and what they will like. But parents do not often think of those things; they think more of marrying their children into a richer, stronger tribe, so that when war and bad seasons come there will be the strong, rich tribe to help them. Also, it is better for the child who is married into a good tribe. So that parents do not think much about the children themselves; they think more about the family and the tribe.”

“Why isn’t he married?” I said to Perolli.

“Did they give the girl he wanted to some one else?”

“How could they, when he would have been a baby then?” said Perolli, indignant at my stupidity. “No. When he was old enough to marry he paid the girl’s family and arranged her marriage to some one else. It is well known why he has not married; he does not want to marry a woman of the mountains, and he knows no other women.”

“And in my country,” I said to Lulash, “I think it would be better if parents thought more about the young man’s family.”

“Yes,” he replied, “if they thought about the character of that family, as they would doubtless do in America. Here, they think more about the lands and herds and strong fighting men that the tribe has. I have often thought at night—for I lie awake a great deal, thinking about my people—that we would have better children if the women were free to choose their own husbands. They would choose men who were young and strong and beautiful. Also the young men would choose the strongest and most beautiful girls. There is another thing, too. I believe there is something like a spirit between two people, something that knows more than their brains do about what their children will be, and that that spirit would lead them into better marriages if they could listen to it. I do not say it very well, because there is no word for it, but I understand it. I would like to see my people try the American way,” he repeated.

He rose to his six feet of height, splendid in fine white wool and silken sash, the jewel-studded chains clinking together on his chest, and swung the rifle again on his back. “I will go now to my own house,” he said. “If the zaushka from America would follow me and drink coffee before my fire, the path her feet would take would always be flowery with spring to my eyes.”

There is something contagious in that sort of thing. “Say to him that my feet will be happy on the path,” I said to the amused Perolli.

“Glory to your lips!” said Lulash. “Glory forever to the little feet that brought you to Thethis!”

The little feet were wearing at that moment two pairs of wrinkled, thick woolen stockings, indescribably ludicrous beneath the flapping legs of trousers around which I had not rewound the soaked woolen leggings, and Perolli and I were helpless with laughter as soon as the door had closed behind Lulash.

“How am I ever going to get to his house?” I asked, wiping my eyes.

“Oh, we’ll have somebody make you some goatskin opangi,” said Perolli. “He won’t expect us very soon.” He flung out his arms in a jubilant gesture. “A besa of peace from Shala!” he exclaimed. “I couldn’t have hoped for that! It means peace through the whole north; it means internal security for northern Albania—if I can only get the other tribes to join it.”

Frances and Alex came in, desperately anxious to know what had happened, and we three did a dance of pure delight. It was an inexpressible relief to know that Perolli would get out of Shala alive, and the besa was almost too much.

“But, Perolli,” said Frances, when I had told the whole conversation, “do you mean to say that these people are—are absolutely moral? I mean, as we understand morality? No love making along all these mountain trails? No illegitimate children? Never?”

“Never? Well, I have heard of one case,” said Perolli. “But don’t forget that such a thing would mean a blood feud between tribes. No man would make love to a girl of his own tribe, of course; a tribe traces its ancestry back to a common ancestor, and it would be like an American’s making love to his own sister. And if he seduced a girl of another tribe he would be involving hundreds of people. Men have to respect women in these mountains; they’re killed if they don’t, and not only they, but their families. A blood feud is no joke.

“However, I did hear of its happening once. The man’s family had to send word to the family of the girl to whom he was betrothed, to say that he could not marry her because he was going to have a child by another woman. The three tribes met in council and prevented a blood feud, but the man’s family had to pay his fiancée’s tribe ten thousand kronen, and ten thousand kronen to the family of the man that the other girl was engaged to. Then those two married, and the first man married the girl who was going to have his child. But it was a terrible disgrace to both their families.

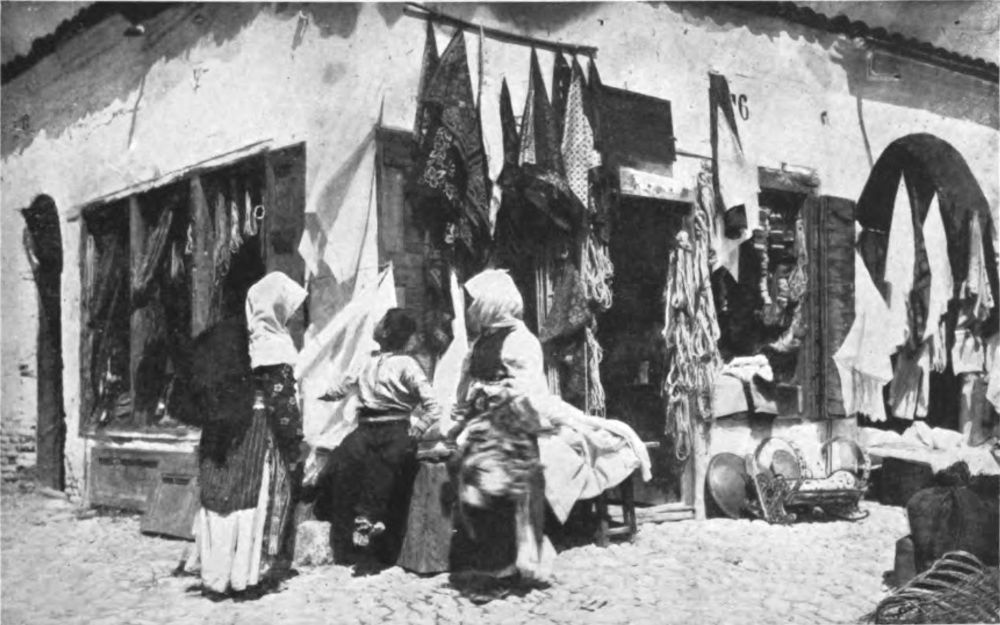

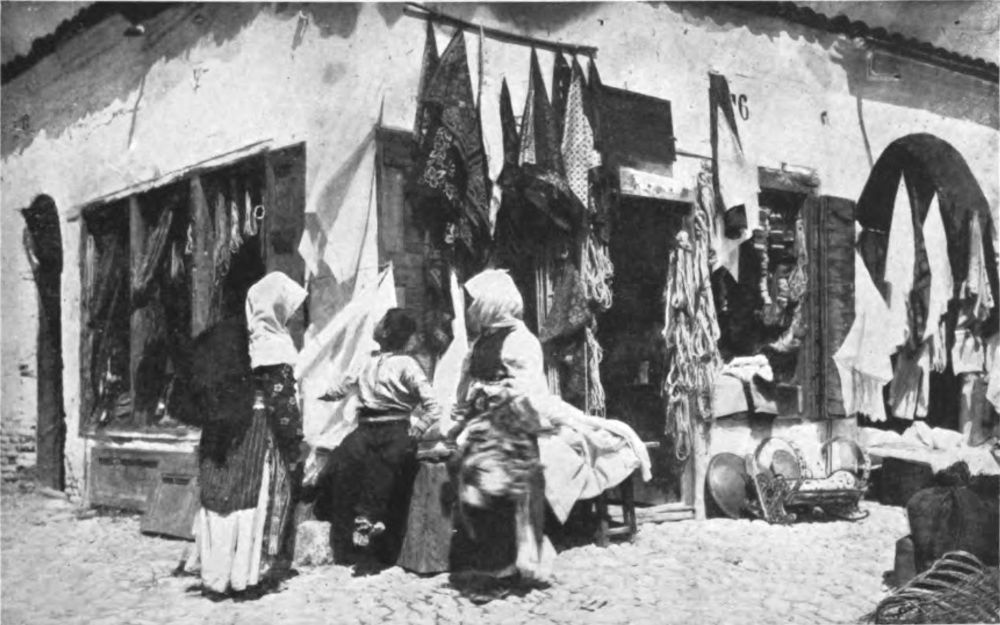

THE SHOPPING CENTER IN TIRANA

These mountain women are admiring the strange weaving and color of bandana handkerchiefs and unbleached muslin from Europe. But they will sigh and content themselves with their own hand-woven silks and cottons, and if they buy anything, it will be the brightly painted cradle. An unbetrothed girl baby who was strapped into so fine a cradle might well hope to be married in Tirana or Scutari.

But he cut short our awed admiration for such a rigidly moral community. He was a man of Ipek, educated in Europe, and returned to Tirana, and his attitude to the ignorant tribes of these mountains was not one of admiration.

“They are really a wretched lot,” he declared. “Now, take a thing like this, for instance.” And he told us that in a house a few miles down the valley there was a nine-year-old girl held prisoner. The story was this:

A man of Pultit had betrothed his unborn child to the unborn child of a man of Shala, eighteen years ago. The two men, being friends, and one evening drinking rakejia together, had agreed that if one child proved to be a boy and the other a girl, they should marry. The wife of the Pultit man had protested; she did not like the tribe of Shala, and she did not like her husband’s friend, perhaps because he was too fond of rakejia. Besides, she was an ambitious woman, and said that if she had a daughter she would marry her in Scutari. Wild, irrational woman! But the compact was made, and nothing was left to her but to hope that both children would be boys, or both girls.

However, she became the mother of a daughter, and the Shala man became the father of a son. The girl was eleven years old, and in a few more years would have been duly married in Shala, when the Serbs and Montenegrins, pouring down over the mountains in the retreat before the Austrians, suddenly invaded Albania, and in fighting those ancestral enemies the girl’s father was killed. The mother immediately took her children and fled to Scutari.

Four years later, the girl now being of marriageable age, Shala sent to Scutari for her, and what was their outrage to discover that the mother not only would not give her up, but had actually betrothed her to a Scutari man! The gendarmes of Scutari make simple and direct justice difficult; mountain law does not apply there. Two Shala men made an attempt to carry off the girl, and were captured by superior forces and thrown into jail. Not killed, you perceive, but trapped, and talked over at length, and kept in a cage for some time, and at length freed, all most absurdly and unreasonably. They returned at once to their task, but they found it impossible to seize the girl again. She was closely guarded, not only by her mother, but by the family of the Scutari man to whom she was unjustly betrothed. So, finding that way to justice blocked, the Shala men caught her little sister, eight years old, and triumphantly escaped with her into the mountains.

She was not yet of marriageable age, and the Shala bridegroom must wait another six years, but justice had been done, though imperfectly. Pultit owed him a bride, and a Pultit bride he would have, with patience. The girl was brought to his house, and was even now being kept there, much against her will, while the family waited for her to grow old enough to be married.

“Those are things that we must change as soon as the government is strong enough,” Perolli said, decisively, and we hoped that the government would be strong enough in time to rescue the girl, though the poor Shala lad, through no fault of his own, seemed doomed to live an unhappy bachelor.

In Padre Marjan’s kitchen we found at least twenty visitors from the village; the men were there again, among them all the chiefs but Lulash. The fireplace was full of bubbling pots and sizzling pans; the padre, helped informally by whoever happened to be nearest, was preparing our luncheon. My dilemma was announced; I stood before them shoeless. A boy ran at once across the village and returned streaming, as though he had been in a river, bringing two pieces of goatskin, tanned with the soft brown hair on it.

To the eager interest of everyone, I set my feet on the pieces, and there were many exclamations of wonder at their smallness and at the curious shape of them, the toes so close together and making a point, instead of arching, each one separately, as the toes of their people do, and they would have been glad to examine them more closely—asking one another, as Rexh explained, if I would or would not take off the strangely woven stockings later. Meanwhile the boy with a nail drew the outlines of my feet on the leather and went away with it to his house, where the opangi would be made.

While this was happening the older men of the tribe went back to the cold bedroom with Perolli, each one adding his own besa of loyalty to the one Lulash had sworn, and asking many questions about the aims and strength of the Tirana government. They would not yet call it the Albanian government; they could not comprehend the idea of the state, so familiar to us that we never examine it. “Government” meant to them not only the consent of the governed, but the active participation of everyone in governing; they had, indeed, no conception of what we mean by “government.” When they say “government” they mean what we mean when we say, in a group, “Well, now we’re all agreed, let’s go on and do it.”

Perolli spent that morning—and indeed most of his time in the few succeeding days that we were together—trying to explain the idea of a representative government to these simple communist people. And he told us that within six weeks the Albanian government would really come up into the mountains. The plan was to begin by sending into the tribes men from Tirana who could read and write; they would be connecting links between Tirana and the tribes, sitting in all the tribal councils, making reports to Tirana and explaining the wishes of the Tirana parliament to the mountaineers.

These men would bring in with them, of course, the private-property ideas of southern Albania (which is just changing from the feudal system to modern capitalism), and I felt a regret, purely romantic, perhaps, at the inevitable disappearance of this last surviving remnant of the Aryan primitive communism in which our own fore-fathers lived, and at the replacing of Lulash by men like our politicians. I am a conservative, even a reactionary; I should like to keep the Albanian mountains what they are. But no one can stop the changes in human affairs; the eternal swing of the pendulum goes on; we have shop stewards in England and a Plumb plan in America, and in Thethis, on the headwaters of the Lumi Shala, we shall have agitators for private ownership of land and houses, and—no doubt, in time—for private property in mines and railroads and electric-power plants.