CHAPTER IV

I HAVE quoted the impressions of Prince Lvoff in regard to Rasputin, and have remarked that I have had personally the opportunity to convince myself that they were correct, at least in their broad lines. The interview which I had with Rasputin in the course of the winter of 1913–14 left me with feelings akin to those experienced by the Prince. This interview took place under the following circumstances: I had been asked by a big American newspaper to see the “Prophet,” whose renown had already spread beyond the Russian frontiers, and who was beginning to be considered as a factor of no mean importance in the conduct of Russian state affairs. This, however, was by no means an easy matter. For one thing, he was seldom in St. Petersburg. He spent most of his time at Tsarskoie Selo, where his headquarters were the apartments of Mme. W. He used to make only brief and flying visits to the capital, where he possessed several dwellings. One never knew in which one he could be found, as he used to go from one to another, according to his fancy. He gave audiences like a sovereign would have done, and before any one was allowed to enter his presence that person had to be subjected to a course of cross-examination so as to make quite sure that no malicious or evil designs were harboured by him in regard to the “Prophet.”

At last, after a succession of unavailing efforts, I chanced to light on a certain Mr. de Bock, with whom Rasputin had business relations, and for whom he procured when the war broke out an important contract connected with the supply of meat for the troops in the field. It was this personage who finally obtained for me the favour of being admitted into the home of Rasputin. The latter was living at the time in a very handsome and expensive flat, in a house situated on the English Prospekt, a rather distant street in St. Petersburg, whose proximity to the quarters of the working population of the capital had appealed to the “Prophet’s” tastes. When I arrived there at about 4 o’clock in the afternoon, I was, first of all, stopped by the hall porter, who wanted me to explain to him where and to whom I was going. Upon hearing that it was to Rasputin he insisted on my taking off my fur coat downstairs, and then examined me most carefully and suspiciously, surveying with special attention the size and volume of my pockets, so as to make sure that I was not carrying any murderous instruments hidden in their depths.

Upstairs the door was opened by an elderly woman with a red kerchief over her head, who, I learned afterward, was one of the “sisters” who followed the “Prophet” everywhere. She asked for my name, and then ushered me into a room, sparely but richly furnished. There some half-dozen people were waiting, in what seemed to me to be extreme impatience, for the door of the next room to open and admit them. Voices were heard through the door angrily discussing something or other. Among the people present I recognised a lady-in-waiting on the Empress, an old general in possession of an important command, two parish priests, three women belonging to the lower classes, one of whom seemed to be in great trouble, and a typical Russian merchant in high boots and dressed in the long caftan which is still worn by some of those who have kept up the traditions of the old school. Then there was a little boy about ten years old, poorly clad, who was crying bitterly. All these people kept silent, but the eager expression on their faces showed that they were all labouring under an intense agitation and emotion. When I entered the apartment a distinct look of disappointment appeared on all their faces. At last the old general approached me, and asked me in more or less polite tones whether I had a special card of admission or not.

“What do you mean?” I inquired.

“Well, you see,” he said, “we all who are in this room have got one, but there”—and he pointed with his finger to the adjoining door—“there sit the people who have come here on the chance, just to try whether Gregory Efimitsch will condescend to speak to them. Some have been sitting there since last night,” he significantly added. And as he spoke he slightly pushed ajar the door he had mentioned. I could see that a room, if anything smaller than the one we were in, was packed full of persons of different ages and types, all of whom looked tired. They were sitting not only on the few chairs which the apartment contained, but also on the floor. There were women with children hanging at their breast, military men, priests, monks, common peasants and two policemen. The last named were seated by the window leisurely eating a piece of bread and cold meat, which they were cutting into small slices with a pocketknife. They had evidently made themselves at home, regardless of consequences or of the feelings of other people. Suddenly we heard another door slam, and a strong step resounded in the hall. A man began to speak in a loud voice. He said: “You just go to see——” and here the name of one of the most influential officials in the Home Office was mentioned, “and you tell him that Gricha has said he was to give you a place, and a good one, too. It does not matter whether there is none vacant, he must find one. There, take this paper, and now go, and don’t forget to show it when you come to the Home Office.”

The door slammed again, and all remained silent for a few minutes. Then the elderly woman who had admitted me, came into the apartment where we were sitting and beckoned me to follow her. But this proved too much for the feelings of the old general who had accosted me on my entrance, and he pushed himself forward in front of me, exclaiming as he did so:

“I have been here a longer time than she has been,” pointing at me with his finger, “and I must get in first.”

“You cannot do so,” replied the woman; “my orders are to let this lady in first.”

“Do you know who I am, woman?” screamed the general at the top of his lungs; he was evidently in a towering passion. “Go at once, and tell Gregory Efimitsch that I must see him at once, I have been waiting here for more than an hour.”

“I cannot do so,” replied the woman, “I must obey the orders that have been given to me.”

“Then I shall do it myself,” exclaimed the general, and he rushed toward the door, which he opened, when he was stopped by a whole torrent of invectives coming from the next room.

“How dare you disobey my orders?” cried out an angry voice. “Thou pig and son of a pig, I have said I wish to see this person and no one else! Thou idle creature! Chuck him out of the room, that pig who dares to contradict me, and you come in here!” And the tall figure of Rasputin appeared on the threshold of the room. He rudely pushed aside the general and, seizing my hand, pulled me into another apartment, which seemed to be his dining room.

It was a rather large corner room with three windows, in which stood a quantity of flowers and green plants. A round table occupied the middle, on which was laid a striped white-and-red tablecloth. A samovar was standing on it, together with glasses on blue-and-white saucers, slices of lemon, sugar in a silver sugar basin, and quantities of cakes and biscuits. Chairs were placed around it, on one of which Rasputin sat down, facing the tea urn, after having made me a sign to do likewise. I noticed that there was a large writing table in one corner covered with books and papers.

The “Prophet” himself did not at all strike me as being the remarkable individual I had been led to expect. He must have been about forty years old, tall and lean, with a long black beard and hair, falling not quite down to his back, but considerably lower than his ears. The eyes were black, singularly cunning in their expression, but did not produce, at least not on me, the uncanny impression I had been told they generally made on those who saw them for the first time. The hands were the most remarkable thing about the man. They were long and thin, with immense nails, as dirty as dirty could be. He kept moving them in all directions as he spoke, sometimes folding them on his breast and sometimes lifting them high up in the air. He wore the ordinary dress of the Russian peasant, high boots and the caftan, which, however, was made of the best and finest dark-blue cloth. What could be seen of his linen was also of the best quality.

After having beckoned to me to sit down, Rasputin poured out some tea in a glass and proceeded to drink it, sipping the beverage slowly out of the saucer into which he poured it out of the glass which he had just filled. Suddenly he pushed the same saucer toward me with the word:

“Drink.”

As I did not in the least feel inclined to take his remains, I declined the tempting offer, which made him draw together his black and bushy eyebrows with the remark:

“Better persons than thou art have drunk out of this saucer, but if thou wantest to make a fuss it is no concern of mine.”

And then he called out, “Avdotia! Avdotia!” The elderly woman who had opened the door for me hastened to come into the room.

“There,” said Rasputin, “this person”—-pointing toward me with his forefinger—“this person refuses to drink out of the cup of life; take it thou instead.”

The woman instantly dropped on her knees and Rasputin proceeded to open her mouth with his fingers and pour down her throat the tea which I had disdained. She then prostrated herself on the ground before him and reverently kissed his feet, remaining in this attitude until he pushed her aside with his heavy boot and said, “There, now thou canst go.”

Then he turned to me once more. “Great ladies, some of the greatest in the land, are but too happy to do as this woman has done,” he said dryly. “Remember that, daughter.”

Then he proceeded at once with the question, “Thou hast wished to see me. What can I do for thee? I am but a poor and humble man, the servant of the Lord, but sometimes it has been my fate to do some good for others. What dost thou require of me?”

I proceeded to explain that I wanted nothing in the matter of worldly goods, but asked this singular personage to be kind enough to tell me for the paper which I represented whether it was true that but for him Russia would have declared war upon Austria the year before.

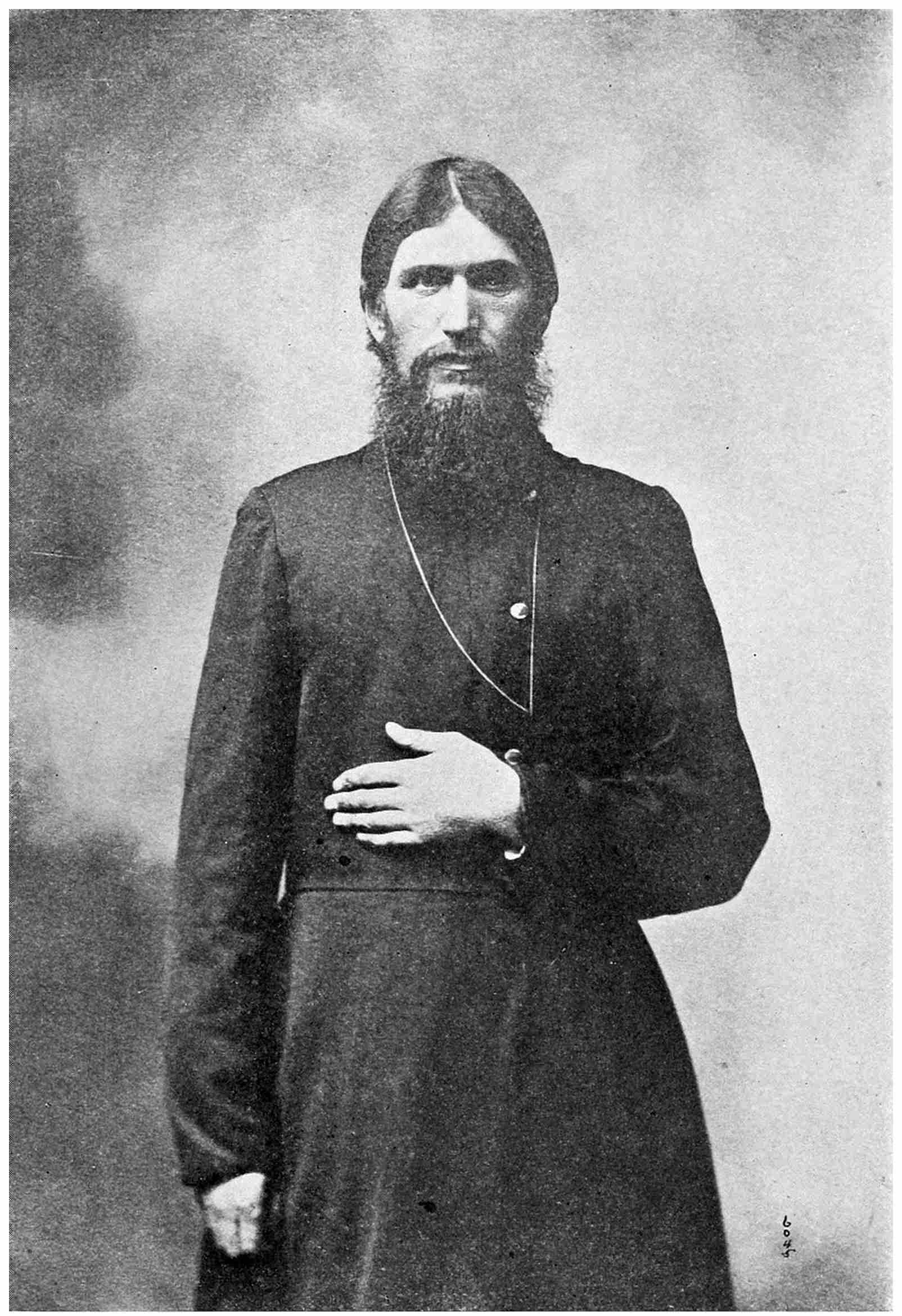

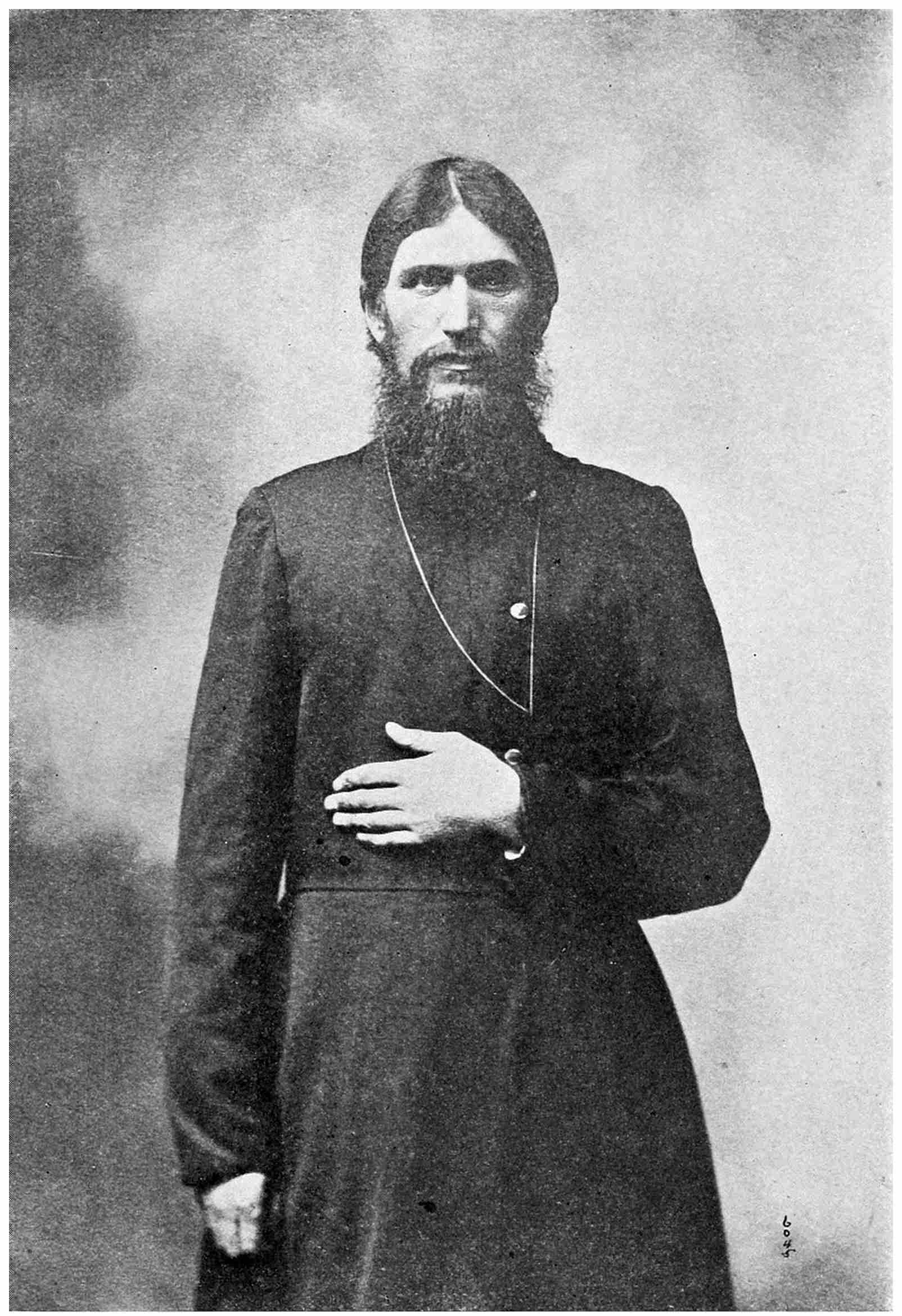

Photograph, International Film Service, Inc.

GREGORY RASPUTIN

“Who has told you such a thing?” he inquired.

“It is a common saying in St. Petersburg,” I replied, “and some people say that you have been right in doing so.”

“Right? Of course, I was right,” he answered with considerable irritation. “All these silly people who surround our Czar would like to see him commit stupidities. They only think about themselves and about the profits which they can make. War is a crime, a great crime, the greatest which a nation can commit, and those who declare war are criminals. I only spoke the truth when I told our Czar that he would be ruined if he allowed himself to be persuaded to go to war. This country is not ready for it. Besides, God forbids war, and if Russia went to war the greatest misfortunes would fall upon her. I only spoke the truth; I always speak the truth, and people believe me.”

“But,” I remarked, “no one can understand how it is that your opinion always prevails in such grave matters. People think that you must have some strange power over men to make them do what you like.”

“And what if I have,” he exclaimed angrily. “They are, all of them, pigs—all these people who want to discuss me or my doings. I am but a poor peasant, but God has spoken to me, and He has allowed me to know what it is that He wishes. I can speak with our Czar. I am not afraid to do so, as they all are. And he knows that he ought to listen to me, else all kind of evil things would befall him. I could crush them all, all these people who want to thwart me. I could crush them in my hand as I do this piece of bread,” and while he was speaking he seized a biscuit out of a plate on the table and reduced it to crumbs. “They have tried to send me away, but they will never get rid of me, because God is with me and Gricha shall outlive them all. I have seen too much and I know too much. They are obliged to do what I like, and what I like is for the good of Russia. As for these ministers and generals, and all these big functionaries whom every one fears in this capital, I do not trouble about them. I can send them all away if I like. The spirit of God is in me and will protect me.

“Thou canst say this to those who have sent thee to see me. Thou canst tell them that the day will come when there will be no one worth anything in our holy Russia except our Czar and Gricha, the servant of God. Yes, thou canst tell them so, and be sure that thou dost it.”

I protested that I should consider this my first duty, but at the same time begged “the servant of God,” as he called himself, to explain to me by what means he had acquired the influence which he possessed.

“By telling the truth to people about themselves,” he quickly replied. “Thou probably thinkest that all these fine ladies about the court who come to me do not care to be told about their failings. But there it is that thou art mistaken. They feel so disconcerted when they hear me call them by their proper names and remind them that they are but b——s, and the daughters of b——s, that they immediately fall at my feet. A silly lot are these women, and Gricha is not such a fool as one thinks. He knows how they ought to be treated. Wilt thou see how I treat them?”

I said that nothing would give me more pleasure. Rasputin went to the door and called Avdotia.

“Go to the telephone,” he said when she came in, “ask the Countess I—— to come at once. She must come herself to the telephone, and if a servant replies, say that he must call her immediately, and then tell her that I require her presence here at 12 o’clock to-night; not one minute earlier or later, mind.”

The woman went away, and I could hear her talking at the telephone in the next room in an authoritative tone. Soon she returned with the words:

“The Countess sends her humble respects to Gregory Efimitsch, and she will be here at midnight as she has been ordered to.”

Rasputin turned toward me with a triumphant smile on his coarse cunning countenance.

“Thou canst see, they are losing no time to obey me. Thou dost not know what women are, and how they like to be handled. Wait, and thou shalt see something better. Avdotia,” he called again. “Is Marie Ivanovna here?” he asked, when she came in response to his call. “Yes, since three hours,” was the reply. “Call her here.”

A young woman of about twenty-five years of age appeared. She was very well dressed in rich furs, and ran up to Rasputin, kneeling before him, and kissing with fervour his dirty hands.

“How long hast thou been here?” he asked.

“About three hours, Batiouschka,” she answered.

“This is well, thou art to remain here until midnight, and neither to eat or to drink all that time, thou hearest?”

“Yes, Batiouschka,” was the reply, uttered in timid, frightened tones.

“Now go into the next room, kneel down before the Ikon, and wait for me without moving. Thou must not move until I come.”

She kissed his hands once more, prostrated herself on the floor before him three times in succession, and then retired with the look of being in a kind of trance during which she could neither know nor understand what was happening to her.

“If thou carest, thou canst follow her, and see whether she obeys me or not,” said Rasputin in his usual dry tone.

I declined the invitation, protesting that I had never doubted but that the “Prophet” would be obeyed, adding, however, that though I had understood he could control the fancies and imagination of women gifted with an exalted temperament, yet I was not convinced that his influence could be exerted over unemotional men, and that this was the one point which interested my friends.

“Thou must not be curious,” shouted Rasputin. “I am not here to tell thee the reasons for what I choose to do. It should suffice thee to know that I would at once return to Pokrovskoie if ever I thought my services were useless to my country. Russia is governed by fools. Yes, they are all of them fools, these pigs and children of pigs,” he repeated with insistence. “But I am not a fool. I know what I want, and if I try to save my country, who can blame me for it?”

“But Gregory Efimitsch,” I insisted, “can you not tell me at least whether it is true that some ministers do all that you tell them?”

“Of course, they do,” he replied angrily. “They know very well their chairs would not hold them long if they didn’t. Thou shalt yet see some surprises before thou diest, daughter,” he concluded with a certain melancholy in his accents.

Avdotia entered the room again.

“Gregory Efimitsch,” she said, “there is Father John of Ladoga waiting for you.”

“Ah! I had forgotten him.” Then he turned toward me.

“Listen again,” he said; “this is a priest, very poor, who is seeking to be transferred into another parish somewhere in the south. Avdotia, call on the telephone the secretary of the Synod and tell him that I am very much surprised to hear that Father John has not yet been appointed to another parish. Tell him this must be done at once, and that he must have a good one. I require an immediate answer.”

The obedient Avdotia went out again, and we could hear her once more talk on the telephone. “The secretary of the Synod presents his humble compliments to you, Batiouschka,” she said when she returned.

“Who cares for his compliments?” interrupted Rasputin. “Will the man have his parish or not? This is all that I want to know.”

“The order for his transfer will be presented for the Minister’s signature to-morrow,” said Avdotia.

“This is right,” sighed Rasputin with relief. And then turning to me:

“Art thou satisfied?” he asked, “and hast thou seen enough to tell to thy friends?”

I declared myself entirely satisfied.

“Then go,” said Rasputin. “I am busy and cannot talk to thee any longer. I have so much to do. Everybody comes to me for something, and people seem to think that I am here to get them what they need or require. They believe in Gricha, these poor people, and he likes to help them. But as for the question of war, this is all nonsense. We shall not have war, and if we have, then I shall take good care it will not be for long.”

He dismissed me with a nod of his head, and his face assumed quite a shocked look when he found that I was retiring without seeming to notice the hand which he was awkwardly stretching out to me. But I knew that he expected people, as a matter of course, to kiss his dirty fingers, and as I was not at all inclined to do so, I made as if I did not notice his gesture. As I was passing into the next room, I could perceive through a half open door leading into another apartment the young lady whom Rasputin had called Marie Ivanovna. She was prostrated before a sacred image hanging in a corner, with a lamp burning in front of it, with her eyes fixed on Heaven, and quite an illuminated expression on her otherwise plain features. St. Theresa might have looked like that. But seen in the light of our incredulous Twentieth Century, she appeared a worthy subject for Charcot, or some such eminent nerve doctor, and her place ought to have been the hospital of “La Salpetriere” rather than the den of the modern Cagliostro, who was making ducks and drakes out of the mighty Russian Empire.

As I was going down the stairs, I met an old man slowly climbing them, with a little girl whom he was half carrying, half dragging along with him. He stopped me with the question:

“Do you happen to know whether the blessed Gregory receives visitors?”

I replied that the “Prophet” was at home, but that I could not say whether he would receive any one or not.

“It is for this innocent I want to see him,” moaned the man. “She is so ill and no doctor can cure her. If only the blessed Gregory would pray over her, I know that she would be well at once. Do you think that he will do so, Barinia?” the man added anxiously.

“I am sure he will,” I replied, more because I did not know what to say rather than from the conviction that Rasputin would receive this new visitor. I saw the old creature continue his ascent up the staircase, and the whole time he was repeating to the child, “You shall get well, quite well, Mania, the Blessed One shall make you quite well.”

On the last steps before the stairs ended on the landing, two men were busy talking. They were both typical Israelites, with hooked nose and crooked fingers. They were discussing most energetically some subject which evidently was absorbing their attention to an uncommon degree, and discussing it in German, too.

“You are quite sure that we can offer him 20 per cent?” one was saying.

“Quite sure, the concession is worth a million; the whole thing is to obtain it before the others come on the scene.”

“Who are the others?” asked the first of the two men.

“The Russo-Asiatic Bank,” replied the second. “You see the whole matter lies in the rapidity with which the thing is made. The only one who can persuade the minister to sign the paper is the old man upstairs,” and he pointed out toward Rasputin’s apartment. Thereupon the two in their turn started to mount the steps.

My first interview with Rasputin, all the details of which I wrote down in my diary when I got home, gave me some inkling as to the different intrigues which were going on around this remarkable personage. It failed, however, to make me understand by what means he had managed to acquire, if he really acquired, a fact of which I still doubted, the strong influence which he liked to give the impression he exercised. It was quite possible that he had contrived through the magnetic gifts with which he was endowed to subdue to his will the hysterical women, whose bigotry and mystical tendencies he had exalted to the highest pitch possible. But how could he, a common peasant, without any education, knowledge of the world or of mankind, have imbued ministers and statesmen with such a dread that they found themselves ready to do anything at his bidding and to dispense favours, graces and lucrative appointments to the people whom he called to their attention. There was evidently something absolutely abnormal in the whole thing, and it was the reason for this abnormality that I began to seek.

This search did not prove easy at first, but in time, by talking with persons who saw much of Rasputin and of the motley crew which surrounded him, I contrived to form some opinion as to the cause of his success. It seemed to me that he was the tool of a strong though small party or group of men, desirous of using him as a means to attain their own ends. There is nothing easier in the world than to make or to mar a reputation, and it is sufficient to say everywhere that a person is able to do this or that thing, to instil into the mind of the public at large the conviction that such is the case. This was precisely what occurred with Rasputin.

Count Witte, who was one of the cleverest political men in his generation and perhaps the only real statesman that Russia has known in the last twenty-five years, ever since his downfall had been sighing for the day when he should be recalled to power. He knew very well all that was going on in the Imperial family, and it was easier for him than for any one else to resort to the right means to introduce an outsider into that very closed circle which surrounded the Czar. So long as he had been a minister and had under his control the public exchequer it had been relatively easy for him to obtain friends, or rather tools, that had helped him in his plans and ambitions. When this faculty for persuasion failed him he bethought himself to look elsewhere for an instrument through which he might still achieve the ends he had in mind. He was not the kind of man who stopped before any moral consideration. For him every means was good, provided it would prove effective. When he saw that certain ladies in the entourage of the sovereigns had become imbued with the Rasputin mania, he was quick to decide that this craze might, if properly managed, prove of infinite value to him. He therefore not only encouraged it as far as was in his power by pretending himself to be impressed by the prophetic powers of the “Blessed Gregory,” but he also contrived very cleverly to let the fact of the extraordinary ascendancy which Rasputin was rapidly acquiring over the minds of powerful and influential persons become known. Very soon everybody talked of the latter-day saint who had suddenly appeared on the horizon of the social life of St. Petersburg, and the fame of his reputation spread abroad like the flames of some great conflagration.

Russia is essentially the land where imperial favourites play a rôle, and soon the whole country was not only respecting Rasputin, but was trying to make up to him and to obtain, through him, all kinds of favours and material advantages. Together with Count Witte a whole political party was working, without the least consideration for the prestige of the dynasty which it was discrediting, to show up the rulers as associated with the common adventurer and sectarian, who, under other conditions, would undoubtedly have found himself prosecuted by the police authorities for his conduct. They had other thoughts in their heads than the interests of the dynasty, these money-seeking, money-grubbing, ambitious men. They represented nothing beyond the desire to become powerful and wealthy. What they wanted was important posts which would give them the opportunity to indulge in various speculations and more or less fraudulent business undertakings they contemplated.

Russia at the time was beginning to be seized with that frenzy for stock-exchange transactions, share buying and selling, railway concessions and mining enterprises which reached its culminating point before the beginning of the war. Men without any social standing, and with more than shady pasts, were coming forward and acquiring the reputation of being lucky speculators capable in case of necessity of developing into clever statesmen. These men began to seek their inspirations in Berlin, and through the numerous German spies with which St. Petersburg abounded they entered into relations with the German Intelligence Department, whose interests they made their own, because they believed that a war might put an end to the industrial development of the country, and thus interfere with their various speculations. The French alliance was beginning to bore those who had got out of it all that they had ever wanted; it was time something new should crop up, and the German and Russian Jews, in whose hands the whole industry and commerce of the Russian Empire lay concentrated, began to preach the necessity of an understanding with the great state whose nearest neighbour it was. A rapprochement between the Hohenzollerns and the Romanoffs began to be spoken of openly as a political necessity, and it was then that, thanks to a whole series of intrigues, the Czar was induced to go himself to Berlin to attend the nuptials of the only daughter of the Kaiser, the Brunswick.

This momentous journey to Berlin was undertaken partly on account of the representations of Rasputin to the Empress, whose love for peace was very well known. Europe had just gone through the anxiety caused by the Balkan crisis, and it was repeated everywhere in St. Petersburg that a demonstration of some kind had to be made in favour of peace in general and also to prove to the world that the great Powers were determined not to allow quarrels in Serbia, Bulgaria and Greece to trouble the security of the world. The marriage festivities of which Berlin became the theatre at the time seemed a fit opportunity for this demonstration. The bureaucratic circles in the Russian capital and the influence of Rasputin were used to bring about this trip of the Czar.

Rasputin was thus fast becoming a personage, simply because it suited certain people—the pro-German party, to use the right word at last—to represent him as being important. They pushed things so far that many ministers and persons in high places refused on purpose certain things which were asked of them and which were absolutely easy for them to perform simply because they wished Rasputin to ask for them for those who were weary of always meeting with a non possumus in questions for which they required the help of the Administration.

Rasputin’s various intermediaries, through whom one had to pass before one could approach him, sold their help for more or less large sums of money, and thus began a period of vulgar agiotage, to use the French expression, of which Russia was the stage, and Rasputin, together with the men who used him, the moving spirits. I very nearly said the evil spirits. But of this, more later on.