CHAPTER II

BY the side of this Monarch in whom his subjects at last lost every vestige of confidence, there stood a sinister figure, the bad genius of a reign that would most probably have been far more peaceful if it had not been there: the figure of his wife, the Empress Alexandra Feodorovna, “the German,” as she had been called even long before the present war broke out. It was undoubtedly to her that were due, at least to a considerable extent, the various misfortunes which have assailed the unfortunate Nicholas II., and it was also she, who, in the brief space of a few short years, discredited him together with the throne to which he had raised her. It was she who destroyed all the prestige which the Monarchy had retained in Russia, until the day when she tarnished it. She was another Marie Antoinette, without any of the qualities, or the courage that had distinguished the latter, who had become the object of the hatred and furious dislike of her subjects, more on account of the vices which were attributed to her, than of those which she really possessed. In regard to the Consort of the Czar Nicholas II., it was just the contrary that occurred, because the general public never became aware of all the strange details concerning the private life of this Princess, who compromised by her conduct the inheritance of her son, together with the Crown which she herself wore. On her arrival in Russia she had been met with expressions of great sympathy, and it would have been relatively easy for her to make herself liked everywhere and by everybody, because the peculiar circumstances which had accompanied her marriage had won for her a sincere popularity all over Russia. At the time she arrived there as the bride of the future Sovereign there existed in the country a strong current of anglomania, which disappeared later on, to revive again during the last year or two. The Princess who came to Livadia from Darmstadt was the granddaughter of Queen Victoria of Great Britain, by whom she had been partly brought up, a fact which spoke in her favour because it was supposed that her education would have developed in her liberal opinions, love for freedom, and the desire to make herself liked as well as respected by her future subjects, who received her with the more enthusiasm that they all hoped she would influence in the right direction her husband, whose weakness of character was already at that time known by those who had had the opportunity of becoming acquainted with him. One felt therefore inclined to forgive her any small mistake she might be led into committing during those first days which followed upon her arrival in her new Fatherland. One pitied this young bride, whose marriage was to follow so soon the funeral of the monarch whose untimely death was lamented so deeply by the whole of Russia, and one felt quite disposed, at least among the upper classes of St. Petersburg society, as well as in court circles, to show oneself indulgent in regard to the almost inevitable errors into which she might fall, at the beginning of her career as an Empress. This feeling was so strong that during the first months which followed upon her marriage, the popularity of her mother-in-law, who had been so sincerely loved before, suffered as a consequence of this general wish to make an idol of Alexandra Feodorovna. The eyes of everybody were turned towards the new star that had arisen on the horizon of the Russian capital.

Amidst this general concert of praise which arose on all sides in honour of the newly wedded Empress, there were a few persons who, having had the opportunity to listen to some discordant notes, kept aloof and waited for what the future would bring. At the time of the death of Alexander III., a man belonging to the prominent circles of Russian society, who had been for a long period of years upon terms of personal friendship with the German Royal Family, happened to be in Berlin, and during a visit which he paid to the Empress Frederick, the aunt of the future wife of the new Czar, he told her how many hopes were set in Russia upon her young niece. He was very much surprised to hear the Empress express herself with a certain scepticism in regard to the bride, and finally say that she felt afraid the Princess Alix, as she was still called at the time, would not understand how to make herself beloved by her subjects, or how to win their hearts. Seeing the astonishment provoked by her remark, she added that the character of the girl about to wear the crown of the Romanoffs, was an exceptionally haughty and proud one, and that as in addition to this defect she was possessed of an unusual amount of vanity, she would most probably have her head turned by the grandeur of her position, and would put forward, in place of the intelligence which she did not possess, an exaggerated feeling of her own importance. The gentleman to whom I have referred returned therefore to Russia with fewer illusions concerning Alexandra Feodorovna than the generality of his compatriots indulged in.

I must give the latter their due, they did not keep these illusions for any length of time, because from the very beginning of her married life the new Czarina contrived to wound the feelings and the susceptibilities of all those with whom she was thrown into contact. She had absolutely no tact, and she fancied that if she allowed herself to be amiable in regard to any one, she would do something which was below her dignity. She applied herself to treat everybody from the height of her unassailable position, and she took good care never to say one word that might be interpreted in the light of a kindness or amiability towards the people who were being presented to her, so that though they tried hard to attribute her utter want of politeness to a timidity which in reality did not exist, yet they felt offended at it. Russian society had been used to something vastly different, and to a certain familiarity in its relations with its Sovereigns. The mother of Nicholas II., the Empress Marie, had been worshipped for the incomparable charm of her manners, and the simple kindness with which she received all those who were introduced to her, asking them to sit down beside her, and talking with them in a charming chatty way, full of sweet and unassuming dignity. Her daughter-in-law abolished these morning receptions which had brought the Sovereign into close intercourse with so many different people. She received the ladies who had asked to be presented to her, standing, surrounded by her court, with two pages behind her holding her train, and she merely stretched out her hand to be kissed by those whom she condescended to admit into her august presence, without speaking one single word to them. Of course the people whom she treated with such rudeness felt hurt at it, and it began to be said among the public that the Empress was not at all amiable, and people abstained from seeking her presence or appearing at Court, unless it was absolutely necessary to do so, leaving thus the field free to people devoid of self respect, to whom one impoliteness more or less did not matter. The balls at the Winter Palace, which formerly had been such brilliant ones, became dull and monotonous. The smile of the Empress Marie was no longer there to enliven them. At last the Czarina left off giving any, and no one missed them, or felt the worse for their absence. One felt rather relieved than otherwise not to be compelled any longer to appear in the presence of the Empress.

As time went on, an abyss was formed which divided the Consort of Nicholas II. from her subjects, whose feelings manifested themselves quite openly on the day of the solemn entry of the Imperial Family into Moscow, on the eve of the Coronation of the new Sovereigns. The golden carriage that contained the Dowager Empress was followed all along its way by the cheers of the population of the ancient capital, whilst a tragic silence prevailed during the passage of the coach in which sat her daughter-in-law. The contrast was such a striking one that it was everywhere noticed and commented upon.

This latent animosity, the first signs of which manifested themselves on this memorable occasion, became even more acute after the catastrophe of Khodinka. Russia did not forgive its Empress for having danced the whole of the night that had followed upon it, and for having given no sign of regret at a disaster that had cost the life of more than twenty thousand people, who had perished in the most awful manner possible. The divorce between her and her subjects was accomplished definitely after that day, and without any hope of a future reconciliation coming to annul its effects.

This unpopularity, and let us say the word, this hatred of which she became the object, did not remain unknown to the Empress, who either noticed it herself, or else was enlightened on the point by her German relatives, with whom she had remained upon most intimate and affectionate terms. She attributed it at first to the fact that she had not during many years given a son to her husband and an heir to the Russian Throne, but later on she was compelled to acknowledge that the dislike which she inspired was due to other causes which were dependant on her own self. The discovery angered and soured her, and made her nasty and ill natured. She tried to avenge herself by the assumption of an authority in the exercise of which she found a certain pleasure, because it procured her at least the illusion of an absolute power, allowing her, if the wish for it happened to cross her mind, to crush all those who were bold enough to criticise any of her actions or her general demeanour.

Her character was obstinate without being firm. She believed herself in all earnestness to be the equal of her husband, and did not think of herself at all as his first subject, so that, instead of giving to others the example of deference towards their Sovereign, she applied herself to lower him down to her own level, to diminish his importance, and to show quite openly that she did not in the very least respect either him or the throne which he occupied. One heard a number of anecdotes on the subject, among others one to the effect that during a regimental feast, at which the Imperial Family was present, the Empress, who had arrived a little in advance of the Czar, did not rise from her seat when he entered the riding school in which the guests were assembled to receive him. This want of deference was commented upon in unfavourable terms, and caused such a scandal that Alexandra Feodorovna was taken to task for it by her mother-in-law, with the only result that she impertinently told the latter to mind her own business and to hold her tongue. The Dowager Empress did not allow her to repeat such a remark, and withdrew herself almost entirely from the Court, much to the regret of all her admirers. All these things were perhaps not important ones, at least from other points of view than the purely social one, but they constituted this drop of water, which by its constant and continual dripping ends in attacking the solidity of the hardest granite. Very soon it became a subject of general knowledge that no one cared for the Empress, and one came to the conclusion that this initial want of sympathy would easily become very real and implacable hatred.

The woman who had become the object of it, instead of trying to fight against the general dislike which she inspired, did absolutely nothing to try to persuade her subjects that she was not the detestable being she had been represented to be, but that she cared for their welfare, in spite of her cold appearance. The haughty and mistaken pride which was one of the chief features in her strange character, led her to retire within herself and to try to avoid seeing the people, who by that time had grown to meet her whenever she appeared in public, with angry and unpleasant expressions in their faces. The Imperial Court under her rule was quickly transformed from the brilliant assemblage it had been into a desert—a solitude no one cared to disturb. The Empress amused herself chiefly in turning tables and in evoking spirits from the other world, in company with mediums of a low kind who abused the confidence that she so unwisely and unnecessarily placed in them, and predicted for her (as it was to their interest to do) a happy and prosperous future.

Then came the war with Japan, together with the disasters which attended it, a war that shook most seriously the prestige of the throne of the Romanoffs. It brought to light all the defects, the disorder, and the inefficiency of the War Office; it enlightened the nation as to the real worth of the people who were standing at the head of its government, and it sounded the first knell of the Revolution which was at last accomplished. This war afforded another pretext to the public for attacking the personality of the Empress, who according to the rumours which circulated at the time, had only looked upon it from the joyous and glorious side, and never noticed its earnest and sad one. It is a fact that neither disasters like those of Moukhden and Tschousima, nor even the revolutionary movement that broke out in consequence of them, affected her equanimity. She remained absolutely cold in presence of these grave events and was absorbed in the joy of the new maternity, which just at that time was granted to her—the birth of the long expected and hoped for Heir to the Russian Throne, which occurred in the very midst of the Japanese campaign. This event certainly did not contrive to make her more popular among her subjects, whilst on the other hand it increased considerably her importance, so that after the appearance in the world of the son she had so ardently wished for, she began to display more independence in her conduct than had been formerly the case, and to discuss more eagerly, and more authoritatively than she had ever been able to do before, matters of State which her position as the mother of the future Sovereign gave her almost a right to know, and to interfere with. She brought forward her own opinions and judgments, which never once proved in accord with the real needs of the Russian people. The Empress was neither good, kind, nor compassionate. Her nature was cold, hard and imperious, and she had never been accessible to the divine feeling which is called pity for other people’s woes. She would have signed a death warrant with the greatest coolness and indifference, and more than once her husband decided, thanks to her intervention, to confirm those submitted to his consideration. This last fact became known, and, as may be imagined, it did not procure her any sympathy among her subjects.

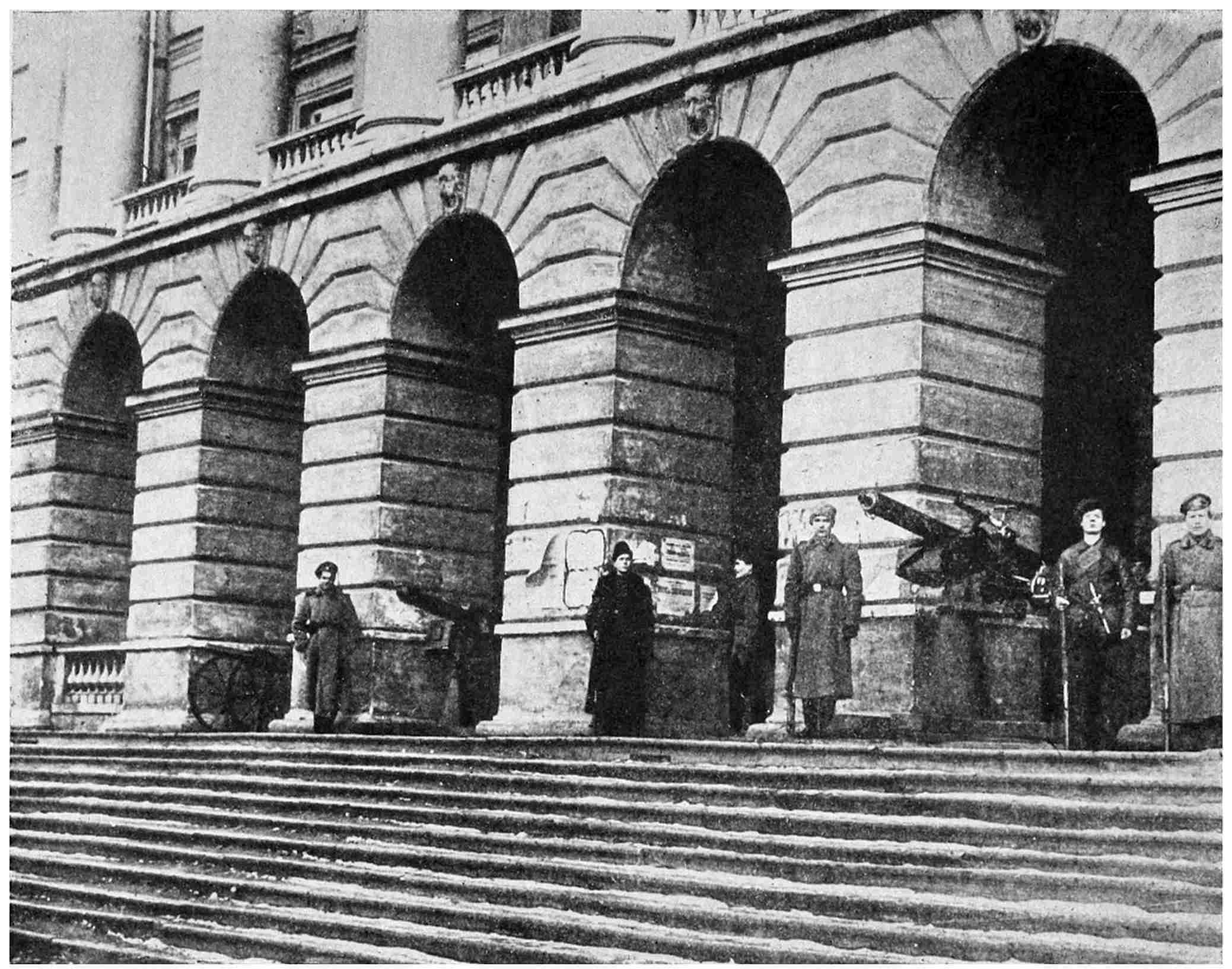

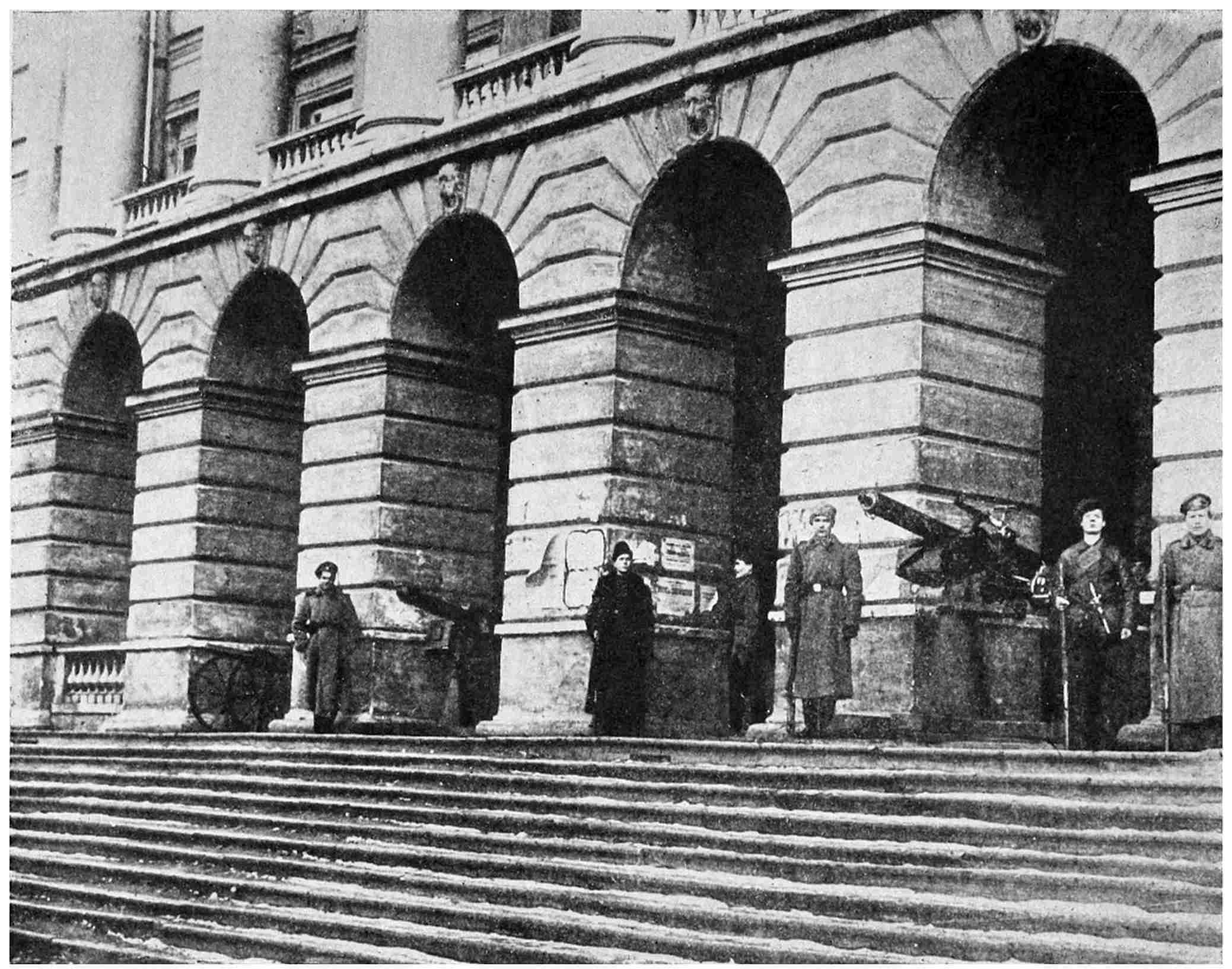

Copyright, International Film Service, Inc.

THE BOLSHEVIKI HEADQUARTERS IN PETROGRAD

It was about that time, that is just before the birth of the Heir to the Throne, and whilst the war with Japan was being fought, that people began to spread dark rumours concerning the private life of Alexandra Feodorovna. A most extraordinary friendship which she contracted with a lady whose reputation left very much to be desired, and who had been divorced from her husband under circumstances that had given rise to much talk, Madame Wyroubieva, was severely criticised. The Empress remained deaf to all the hints which were conveyed to her on the subject. She kept the lady in question beside her, gave her rooms in the Imperial Palace, and took her about with her wherever she went, without minding in the least the impression which this bravado of public opinion produced everywhere. Another friendship for a certain Colonel Orloff, an officer in her own regiment of lancers, also gave rise to considerable gossip, which increased in intensity when after the death of the latter, who committed suicide under rather mysterious circumstances, the Empress repaired every afternoon to the churchyard where he was buried, prayed and laid flowers upon his grave. One wondered why she did such strange things, and of course persons were at once found to explain her motives in a manner which was the reverse of charitable.

The Emperor knew and saw all that was going on, but said nothing. His wife by that time had acquired over his mind quite an extraordinary influence, and either he did not dare to make any remarks as to the originality which she displayed in her conduct, or else he imagined that her position put her so much above criticism that it was useless to interfere with what she might feel inclined to do in the matter of eccentricity. A legend soon established itself in regard to Alexandra Feodorovna. She was said to suffer from a nervous affection, which obliged her at times to keep to her own apartments, and not to appear in public. People tried, thanks to this pretext, to explain her absence on different occasions when her position would have required her to show herself to her subjects. But the truth of the matter was that the Empress did not wish to see anybody, outside the small circle of people before whom she need not constrain herself to be amiable or pleasant; and that utterly forgetful of the duties entailed upon her by her high rank and great position, she wanted only to live according to her personal tastes, surrounded by flatterers or by people resigned beforehand to accept and bow down before her numerous caprices, and to fulfil with a blind obedience all the commands it might please her to issue to them.

She mixed openly in public affairs, and began to play a leading part in the conduct of the State. Her husband never dared to refuse her anything, and the Empress attempted to lead the destinies of Russia in the sense which she had the most at heart, that is in one corresponding to the interests of her own native country. She had remained entirely German in her tastes and opinions, and her English education had had absolutely no influence on her character. Thanks to an active correspondence which she kept up with her brother, the Grand Duke of Hesse, she was able to acquaint the Emperor William II. with a good many things that he would never have learned without her. This is the more curious, if one takes into account the fact that during the first years which had followed upon her marriage, and especially after the different journeys which she had made in France, Alexandra Feodorovna had expressed great sympathy and admiration for everything that was French, perhaps on account of the great enthusiasm with which she had been received by the French population. But later on, thanks to the influence of the unscrupulous people into whose hands she fell, her ideas became transformed, and she boldly tried to fight against the French leanings of her husband, and to lead him towards an alliance with Germany, in which she thought that she saw the advantage, and even the safety of her throne, and of the son she loved above everything else in the world.

All these facts could not long remain unknown, and soon the public began to discuss them, together with the story of the different intrigues of which the Palace of Tsarskoie Selo became the centre. Thanks to the friends whom she had chosen for herself, the ante-chamber of the Empress was transformed into a kind of annex to the Stock Exchange, where all sorts of people, honest or dishonest, used to meet, in order to obtain through her intercession more or less extravagant, if not dangerous, favours. Thanks to Madame Wyroubieva, there were introduced into the intimacy of the Czarina certain members of the orthodox clergy recommendable only by their love for money and for lucrative employments, or rich dioceses and monasteries. The Empress together with her sister, the Grand Duchess Elisabeth, who after the murder of her husband had become a nun and the superior of a cloister which she had founded in Moscow, and to whom one might have applied with success the remark of Marie Antoinette in regard to her aunt Madame Louise of France, “she is the most intriguing little Carmelite in the whole of the kingdom,” tried to mix themselves up in every important matter in the State, and to lead it according to their own lights and aims, making use of the Emperor as of an instrument of their own private ambitions and desires. They were both fierce reactionaries, who from the first day that Nicholas II. had promulgated the Constitution of the 17th of October, had tried to persuade him to recall it. It was thanks to the initiative of the Empress that the first Duma was dissolved, and that the government began to exercise considerable pressure over the elections in order to prevent the candidates whom it believed it could not trust from being chosen by their constituents. One Minister after another of those whom the Czar appointed in rapid succession, resigned their functions, until at last it was an acknowledged fact in Russia that no honest trial of constitutional government could or would be attempted so long as Alexandra Feodorovna would be there to counteract its existence. When the Revolution broke out in the year 1905, and especially at the time of the disturbances which took place in Moscow, it was the Empress who excited her husband to adopt rigorous measures in order to crush it, measures which led to nothing, and which only made Nicholas II. a little more unpopular than he already was among his subjects. It was related, whether true or not I cannot say, that when the famous Semenovsky Regiment was sent to Moscow to reduce into submission the insurrection which had broken out there, Alexandra Feodorovna had desired to say good-bye to the officers before their departure, and that the only recommendation which she had made to them had been not to show any mercy to the insurgents. She had read without understanding it in the very least, the history of the French Revolution in 1789, and one had often heard her say that to show any weakness or compassion in times of danger was equivalent to signing one’s own death warrant. Her friends were nearly all of them men and women with a bad reputation, and amidst the circle of her own immediate family she had only contrived to make herself enemies. Thanks to her influence, and to her petty personal spite, the young Grand Duke Cyril, the son of the Grand Duke Vladimir, was deprived of his titles and dignities and exiled from Russia for having dared to marry his first cousin, the divorced wife of the Empress’s brother, the Grand Duke of Hesse, the Princess Victoria Melita of Edinburgh. This punishment, however, was promptly cancelled, thanks to the numerous protests which followed upon it from all quarters, but the two people concerned never forgave the Empress her attitude in regard to their union, and we saw an echo of this hostility the other day when the Grand Duke Cyril on the outbreak of the Revolution tried to play the part of Philippe Egalité in the Romanoff family, and went with his regiment to put himself at the disposal of the new government appointed by the Duma.

The only brother of Nicholas II., the Grand Duke Michael Alexandrovitsch, saw the influence of the Empress exercised against him in a manner which was even more odious, because she contrived to deprive him of the control not only of his fortune, but also of his personal liberty to manage his estates. With her mother-in-law, the Dowager Empress Marie, Alexandra Feodorovna showed herself absolutely abominable in her disdain, haughtiness and pride. With the persons composing her court and household, she was unpleasant and bitter. Even in regard to her own daughters she proved herself heartless, and she never once during the twenty-three years which followed her arrival in Russia until the day of her downfall, tried to do any good around her or induce her husband to accomplish one of those actions full of generosity and mercy which unite a nation with its Sovereign, and make their hearts beat together for some noble cause or other. Then again there occurred the Rasputin incident. I have discussed it at length in the first part of this book, and shall therefore not enter here into a second description of the career of this strange personage, this low Cagliostro of a reign that did not deserve to have any great nobleman or even gentleman for its favourite. The only thing which I want to point out to the reader, is the responsibility which devolves upon the Empress in this disagreeable story, which more perhaps than anything else hastened the fall of the old Romanoff monarchy. Whether she was really persuaded of the holy character of the sinister adventurer who had contrived so cleverly to exploit her credulity, or whether there was in this curious infatuation for an unworthy object a question of hypnotism, combined with the extravagance of a badly balanced mind and imagination, it is difficult to say, especially when one has not followed otherwise than by hearsay the different incidents of this almost unbelievable tragedy. It is probable that the mystery, such as it was, will never be quite explained, but one may reasonably suppose that the perpetual invocations to spirits of another world, which Alexandra Feodorovna had practised for so many years, have had a good deal to do with the obstinacy with which she insisted upon imposing this personage upon all those who surrounded her, and with which she allowed him to interfere with the details of her family life, a thing which went so far that one day the governess of the young Grand Duchesses, Mademoiselle Toutscheff, a most distinguished lady, went to seek the Emperor, and told him that she could no longer be responsible for the education of his daughters if Rasputin was allowed to enter their apartments at every hour of the day and night. The only reply which was made by Nicholas II. to this communication was that the Empress ought not to be crossed, on account of the state of her nerves. He seemed to approve of everything that was going on in his house, and, this is the point which has always seemed so incomprehensible in his character, he even appeared to view with a certain pleasure the admittance into the intimacy of his home life of this uncivilised and uncouth creature called Rasputin, whose hand Alexandra Feodorovna bent down to kiss with a reverence that she had never before in the course of her whole life shown to any one else, not excepting Queen Victoria of England, whom she had tried to snub during the official visit which she had paid to her after her marriage.

The complete indifference of the Czar as to what was going on around him and under his own roof, combined with his weakness of character and his unreasonable love for his wife, did not add to the feelings of respect that his subjects ought to have entertained for him. In a very short time extraordinary rumours began to circulate concerning all that was supposed to take place at Tsarskoie Selo, rumours which, disseminated as they were among the population of Petrograd, contributed in no small degree to the promptitude with which it rallied itself to the cause of the Revolution that put an end to the reign of Nicholas II. It was related amongst other things that the Commander-in-Chief of the Army, the Grand Duke Nicholas, had one day told his Imperial nephew that if he did not lock up Alexandra Feodorovna in a convent, he would come himself at the head of his troops, to carry her away, and confine her within the walls of the monastery of Novodievitvchy. True or not, the story was repeated everywhere, and it procured for the Grand Duke a considerable number of friends and sympathisers.

Soon after this it was related that the Empress was in connivance with the numerous people who had made it their business to plunder the national exchequer, and that she looked with indulgence upon the malversations from which profited the partisans and the accomplices, for one could hardly call them by another name, of Rasputin. She began to be hated even more ferociously than had been the case before, and at last the police had to let Nicholas II. know that his Consort would do better not to show herself too often in public, because an attempt against her life might easily come to be made, under the influence of all the stories which one heard right and left concerning her private conduct and her affection for a being who was accused by the whole nation of being fatal to Russia’s prosperity at home and good renown abroad. The Czar listened to all this, as he was to listen later on to the remonstrances of his own family, but he did not act on all that he had been told. He continued to see Rasputin, partly because, according to the tales of those who were in the secret of what really went on in that strange Imperial household, the frank way of speaking of this uncouth peasant amused him and pleased him, being something so totally different from the language which he was accustomed to hear. But contrary to what was generally believed, he did not discuss with him matters of State, any more than did the Empress. It is to be hoped that this last assertion is correct, and that Rasputin in regard to Nicholas II. only played the part sustained by Chicot at the court of Henri III. of France, that of the King’s Jester, capable occasionally of telling some truths to his master. But during the last months which preceded the removal of this sinister figure from the horizon of Tsarskoie Selo, no one in Russia would believe in such a version, seeing that this Jester could dispose according to his pleasure of all the high places in the State, that he had created ministers, functionaries of paramount importance, church dignitaries, and that whoever addressed himself to him generally got what he wanted, whilst it was his friends who were controlling the government of the vast empire of the Czars. One did not realise that this had become possible only because all persons endowed with the slightest independence of character, had gradually become estranged from their Sovereign, and had come to the decision to abandon him to his fate, disgusted as they were by his weakness in regard to his wife, and being moreover unwilling to accept the responsibility of duties which they were not allowed to fulfil according to the dictates of their conscience. One after another the Ministers, who at the beginning of the reign of Nicholas II. had helped him to rule Russia, had been dismissed by him, or retired of their own accord, and their places had been taken by simple subaltern functionaries, preoccupied only with that one single thought of remaining as long as possible in possession of the places which they had been called upon by a caprice of destiny to occupy, and for which they knew at heart that they were not fit. Everybody who had a sense of decency left, had fled from Tsarskoie Selo, not caring to enter into conflict with the mysterious and subterranean powers, which, to repeat the words used by Professor Paul Miliukoff in his famous speech in the Duma a few days before the Revolution, alone decided the most important questions in the State. The whole country was disgusted at the conduct of those who ruled it, and this disgust was soon to change into an absolute contempt. The unpopularity of the Empress had extended itself to the person of the Czar himself, whom one was beginning to render responsible for the different things going on under his roof and to accuse of seeing, without any emotion, the Imperial prestige and honour sullied, and this autocracy for which he cared so much dishonoured. This unfortunate Emperor did not find anywhere a support. His mother had been estranged from him; his whole family had turned against him, after numerous and useless attempts to open his eyes as to the dangers which surrounded him and the position in which he stood before his subjects. His brother had been systematically kept away from him by the Empress, who did not care to hav