CHAPTER VIII.

THE STORY OF THE DIAMOND FIELDS.

THE first known finding of a diamond in South Africa was as recent as 1867;—so that the entire business which has well nigh deluged the world of luxury with precious stones and has added so many difficulties to the task of British rule in South Africa is only now,—in 1877,—ten years old. Mr. Morton, an American gentleman who lectured on the subject before the American Geographical Society in the early part of 1877 tells us that “Across a mission map of this very tract printed in 1750 is written, ‘Here be Diamonds;’”—that the Natives had long used the diamonds for boring other stones, and that it was their practice to make periodical visits to what are now the Diamond Fields to procure their supply. I have not been fortunate enough to see such a map, nor have I heard the story adequately confirmed, so as to make me believe that any customary search was ever made here for diamonds even by the Natives. I am indeed inclined to doubt the existence of any record of South African diamonds previous to 1867, thinking that Mr. Morton must have been led astray by some unguarded assertion. Such a map would be most interesting if it could be produced. For all British and South African purposes,—whether in regard to politics, wealth, or geological enquiry the finding of the diamond in 1867 was the beginning of the affair.

And this diamond was found by accident and could not for a time obtain any credence. It is first known to have been seen at the house of a Dutch farmer named Jacobs in the northern limits of the Cape Colony, and South of the Orange river. It had probably been brought from the bed of the stream or from the other side of the river. The “other side” would be, in Griqualand West, the land of diamonds. As far as I can learn there is no idea that diamonds have been deposited by nature in the soil of the Cape Colony proper. At Jacobs’ house it was seen in the hands of one of the children by another Boer named Van Niekerk, who observing that it was brighter and also heavier than other stones, and thinking it to be too valuable for a plaything offered to buy it. But the child’s mother would not sell such a trifle and gave it to Van Niekerk. From Van Niekerk it was passed on to one O’Reilly who seems to have been the first to imagine it to be a diamond. He took it to Capetown where he could get no faith for his stone, and thence back to Colesberg on the northern extremity of the Colony where it was again encountered with ridicule. But it became matter of discussion and was at last sent to Dr. Atherstone of Grahamstown who was known to be a geologist and a man of science. He surprised the world of South Africa by declaring the stone to be an undoubted diamond. It weighed over 21 carats and was sold to Sir P. Wodehouse, the then Governor of the Colony, for £500.[7]

In 1868 and 1869 various diamonds were found, and the search for them was no doubt instigated by Van Niekerk’s and O’Reilly’s success;—but nothing great was done nor did the belief prevail that South Africa was a country richer in precious stones than any other region yet discovered. Those which were brought to the light during these two years may I believe yet be numbered, and no general belief had been created. But some searching by individuals was continued. The same Van Niekerk who had received the first diamond from the child not unnaturally had his imagination fired by his success. Either in 1868 or 1869 he heard of a large stone which was then in the hands of a Kafir witch-doctor from whom he succeeded in buying it, giving for it as the story goes all his sheep and all his horses. But the purchase was a good one,—for a Dutchman’s flocks are not often very numerous or very valuable,—and he sold the diamond to merchants in the neighbourhood for £11,200. It weighed 83 carats, and is said to be perfect in all its appointments as to water, shape, and whiteness. It became known among diamonds and was christened the Star of South Africa. After a law suit, during which an interdict was pronounced forbidding its exportation or sale, it made its way to the establishment of Messrs. Hunt and Rosskill from whom it was purchased for the delight of a lovely British Countess.

Even then the question whether this part of South Africa was diamondiferous[8] had not been settled to the satisfaction of persons who concern themselves in the produce and distribution of diamonds. There seems to have been almost an Anti-South African party in the diamond market, as though it was too much to expect that from a spot so insignificant as this corner of the Orange and Vaal rivers should be found a rival to the time-honoured glories of Brazil and India. It was too good to believe,—or to some perhaps too bad,—that there should suddenly come a plethora of diamonds from among the Hottentots.

It was in 1870 that the question seems to have got itself so settled that some portion of the speculative energy of the world was enabled to fix itself on the new Diamond Fields. In that year various white men set themselves seriously to work in searching the banks of the Vaal up and down between Hebron and Klipdrift,—or Barkly as it is now called, and many small parcels of stones were bought from Natives who had been instigated to search by what they had already heard. The operations of those times are now called the “river diggings” in distinction to the “dry diggings,” which are works of much greater magnitude carried on in a much more scientific manner away from the river,—and which certainly are in all respects “dry” enough. But at first the searchers confined themselves chiefly to the river bed and to the small confluents of the river, scraping up into their mining cradles the shingles and dirt they had collected, and shaking and washing away the grit and mud, till they could see by turning the remaining stones over with a bit of slate on a board whether Fortune had sent on that morning a peculiar sparkle among the lot.

I was taken up to Barkly “on a picnic” as people say; and a very nice picnic it was,—one of the pleasantest days I had in South Africa. The object was to shew me the Vaal river, and the little town which had been the capital of the diamond country before the grand discovery at Colesberg Kopje had made the town of Kimberley. There is nothing peculiar about Barkly as a South African town, except that it is already half deserted. There may be perhaps a score of houses there most of which are much better built than those at Kimberley. They are made of rough stone, or of mud and whitewash; and, if I do not mistake, one of them had two storeys. There was an hotel,—quite full although the place is deserted,—and clustering round it were six or seven idle gentlemen all of whom were or had been connected with diamonds. I am often struck by the amount of idleness which persons can allow themselves whose occupations have diverged from the common work of the world.

When at Barkly we got ourselves and our provisions into a boat so that we might have our picnic properly, under the trees at the other side of the river,—for opposite to Barkly is to be found the luxury of trees. As we were rowed down the river we saw a white man with two Kafirs poking about his stones and gravel on a miner’s ricketty table under a little tent on the beach. He was a digger who had still clung to the “river” business; a Frenchman who had come to try his luck there a few days since. On the Monday previous,—we were told,—he had found a 13 carat white stone without a flaw. This would be enough perhaps to keep him going and almost to satisfy him for a month. Had he missed that one stone he would probably have left the place after a week. Now he would go on through days and days without finding another sparkle. I can conceive no occupation on earth more dreary,—hardly any more demoralizing than this of perpetually turning over dirt in quest of a peculiar little stone which may turn up once a week or may not. I could not but think, as I watched the man, of the comparative nobility of the work of a shoemaker who by every pull at his thread is helping to keep some person’s foot dry.

After our dinner we walked along the bank and found another “river” digger, though this man’s claim might perhaps be removed a couple of hundred yards from the water. He was an Englishman and we stood awhile and talked to him. He had one Kafir with him to whom he paid 7s. a week and his food, and he too had found one or two stones which he shewed us,—just enough to make the place tenable. He had got upon an old digging which he was clearing out lower. He had, however, in one place reached the hard stone at the bottom, in, or below, which there could be no diamonds. There was however a certain quantity of diamondiferous matter left, and as he had already found stones he thought that it might pay him to work through the remainder. He was a most good-humoured well-mannered man, with a pleasant fund of humour. When I asked him of his fortune generally at the diggings, he told us among other things that he had broken his shoulder bone at the diggings, which he displayed to us in order that we might see how badly the surgeon had used him. He had no pain to complain of,—or weakness; but his shoulder had not been made beautiful. “And who did it?” said the gentleman who was our Amphytrion at the picnic and is himself one of the leading practitioners of the Fields. “I think it was one Dr. ——,” said the digger, naming our friend whom no doubt he knew. I need not say that the doctor loudly disclaimed ever having had previous acquaintance with the shoulder.

The Kafir was washing the dirt in a rough cradle, separating the stones from the dust, and the owner, as each sieve-full was brought to him, threw out the stones on his table and sorted them through with the eternal bit of slate or iron formed into the shape of a trowel. For the chance of a sieve-full one of our party offered him half a crown,—which he took. I was glad to see it all inspected without a diamond, as had there been anything good the poor fellow’s disappointment must have been great. That halfcrown was probably all that he would earn during the week,—all that he would earn perhaps for a month. Then there might come three or four stones in one day. I should think that the tedious despair of the vacant days could hardly be compensated by the triumph of the lucky minute. These “river” diggers have this in their favour,—that the stones found near the river are more likely to be white and pure than those which are extracted from the mines. The Vaal itself in the neighbourhood of Barkly is pretty,—with rocks in its bed and islands and trees on its banks. But the country around, and from thence to Kimberley, which is twenty-four miles distant, is as ugly as flatness, barrenness and sand together can make the face of the earth.

The commencement of diamond-digging as a settled industry was in 1872. It was then that dry-digging was commenced, which consists of the regulated removal of ground found to be diamondiferous and of the washing and examination of every fraction of the soil. The district which we as yet know to be so specially gifted extends up and down the Vaal river from the confluence of the Modder to Hebron, about 75 miles, and includes a small district on the east side of the river. Here, within 12 miles of the river, and within a circle of which the diameter is about 2½ miles, are contained all the mines,—or dry diggings,—from which have come the real wealth of the country. I should have said that the most precious diamond yet produced, one of 288 carats, was found close to the river about 12 miles from Barkly. This prize was made in 1872.

It is of the dry diggings that the future student of the Diamond Fields of South Africa will have to take chief account. The river diggings were only the prospecting work which led up to the real mining operations,—as the washing of the gullies in Australia led to the crushing of quartz and to the sinking of deep mines in search of alluvial gold. Of these dry diggings there are now four, Du Toit’s Pan, Bultfontein, Old De Beers,—and Colesberg Kopje or the great Kimberley mine, which though last in the Field has thrown all the other diamond mines of the world into the shade. The first working at the three first of these was so nearly simultaneous, that they may almost be said to have been commenced at once. I believe however that they were in fact opened in the order I have given.

Bultfontein and Du Toit’s Pan were on two separate Boer farms, of which the former was bought the first,—as early as 1869,—by a firm who had even then had dealings in diamonds and who no doubt purchased the land with reference to diamonds. Here some few stones were picked from the surface, but the affair was not thought to be hopeful. The diamond searchers still believed that the river was the place. But the Dutch farmer at Du Toit’s Pan, one Van Wyk, finding that precious stones were found on his neighbour’s land, let out mining licences on his own land, binding the miners to give him one fourth of the value of what they found. This however did not answer and the miners resolved to pay some small monthly sum for a licence, or to “jump” the two farms altogether. Now “jumping” in South African language means open stealing. A man “jumps” a thing when he takes what does not belong to him with a tacit declaration that might makes right. Appeal was then made to the authorities of the Orange Free State for protection;—and something was done. But the diggers were too strong, and the proprietors of the farms were obliged to throw open their lands to the miners on the terms which the men dictated.

The English came,—at the end of 1871,—just as the system of dry digging had formed itself at these two mines, and from that time to this Du Toit’s Pan and Bultfontein have been worked as regular diamond mines. I did not find them especially interesting to a visitor. Each of them is about two miles distant from Kimberley town, and the centre of the one can hardly be more than a mile distant from the centre of the other. They are under the inspection of the same Government officer, and might be supposed to be part of one and the same enterprise were it not that there is a Mining Board at Du Toit’s Pan, whereas the shareholders at Bultfontein have abstained from troubling themselves with such an apparatus. They trust the adjustment of any disputes which may arise to the discretion of the Government Inspector.

At each place there is a little village, very melancholy to look at, consisting of hotels or drinking bars, and the small shops of the diamond dealers. Everything is made of corrugated iron and the whole is very mean to the eye. There had been no rain for some months when I was there, and as I rode into Du Toit’s Pan the thermometer shewed over 90 in the shade, and over 150 in the sun. While I was at Kimberley it rose to 96 and 161. There is not a blade of grass in the place, and I seemed to breathe dust rather than air. At both these places there seemed to be a “mighty maze,”—in which they differ altogether from the Kimberley mine which I will attempt to describe presently. Out of the dry dusty ground, which looked so parched and ugly that one was driven to think that it had never yet rained in those parts, were dug in all directions pits and walls and roadways, from which and by means of which the dry dusty soil is taken out to some place where it is washed and the debris examined. Carts are going hither and thither, each with a couple of horses, and Kafirs above and below,—not very much above or very much below,—are working for 10s. a week and their diet without any feature of interest. What is done at Du Toit’s Pan is again done at Bultfontein.

At Du Toit’s Pan there are 1441 mining claims which are possessed by 214 claimholders. The area within the reef,—that is within the wall of rocky and earthy matter containing the diamondiferous soil,—is 31 acres. This gives a revenue to the Griqualand Government of something over £2,000 for every three months. In the current year,—1877,—it will amount to nearly £9,000. About 1,700 Kafirs are employed in the mine and on the stuff taken out of it at wages of 10s. a week and their diet,—which, at the exceptionally high price of provisions prevailing when I was in the country, costs about 10s. a week more. The wages paid to white men can hardly be estimated as they are only employed in what I may call superintending work. They may perhaps be given as ranging from £3 to £6 a week. The interesting feature in the labour question is the Kafir. This black man, whose body is only partially and most grotesquely clad, and who is what we mean when we speak of a Savage, earns more than the average rural labourer in England. Over and beyond his board and lodging he carries away with him every Saturday night 10s. a week in hard money, with which he has nothing to do but to amuse himself if it so pleases him.

At Bultfontein there are 1,026 claims belonging to 153 claimholders. The area producing diamonds is 22 acres. The revenue derived is £6,000 a year, more or less. About 1,300 Kafirs are employed under circumstances as given above. The two diggings have been and still are successful, though they have never reached the honour and glory and wealth and grandeur achieved by that most remarkable spot on the earth’s surface called the Colesberg Kopje, the New Rush, or the Kimberley mine.

I did not myself make any special visit to the Old De Beer mine. De Beer was the farmer who possessed the lands called Vooruitzuit of the purchase of which I have already spoken, and he himself, with his sons, for awhile occupied himself in the business;—but he soon found it expedient to sell his land,—the Old De Beer mine being then established. As the sale was progressing a lady on the top of a little hill called the Colesberg Kopje poked up a diamond with her parasol. Dr. Atherstone who had visited the locality had previously said that if new diamond ground were found it would probably be on this spot. In September 1872 the territory of Griqualand West became a British Colony, and at that time miners from the whole district were congregating themselves at the hill, and that which was at once called the “New Rush” was established. In Australia where gold was found here or there the miners would hurry off to the spot and the place would be called this or that “Rush.”

The New Rush, the Colesberg Kopje,—pronounced Coppy,—and the Kimberley mine are one and the same place. It is now within the town of Kimberley,—which has in fact got itself built around the hill to supply the wants of the mining population. Kimberley has in this way become the capital and seat of Government for the Province. As the mine is one of the most remarkable spots on the face of the earth I will endeavour to explain it with some minuteness, and I will annex a plan of it which as I go on I will endeavour also to explain.

The Colesberg hill is in fact hardly a hill at all,—what little summit may once have entitled it to the name having been cut off. On reaching the spot by one of the streets from the square you see no hill but are called upon to rise over a mound, which is circular and looks to be no more than the debris of the mine though it is in fact the remainder of the slight natural ascent. It is but a few feet high and on getting to the top you look down into a huge hole. This is the Kimberley mine. You immediately feel that it is the largest and most complete hole ever made by human agency.

At Du Toit’s Pan and Bultfontein the works are scattered. Here everything is so gathered together and collected that it is not at first easy to understand that the hole should contain the operations of a large number of separate speculators. It is so completely one that you are driven at first to think that it must be the property of one firm,—or at any rate be entrusted to the management of one director. It is very far from being so. In the pit beneath your feet, hard as it is at first to your imagination to separate it into various enterprises, the persons making or marring their fortunes have as little connection with each other as have the different banking firms in Lombard Street. There too the neighbourhood is very close, and common precautions have to be taken as to roadway, fires, and general convenience.

You are told that the pit has a surface area of 9 acres;—but for your purposes as you will care little for diamondiferous or non-diamondiferous soil, the aperture really occupies 12 acres. The slope of the reef around the diamond soil has forced itself back over an increased surface as the mine has become deeper. The diamond claims cover 9 acres.

You stand upon the marge and there, suddenly, beneath your feet lies the entirety of the Kimberley mine, so open, so manifest, and so uncovered that if your eyes were good enough you might examine the separate operations of each of the three or four thousand human beings who are at work there. It looks to be so steep down that there can be no way to the bottom other than the aerial contrivances which I will presently endeavour to explain. It is as though you were looking into a vast bowl, the sides of which are smooth as should be the sides of a bowl, while round the bottom are various marvellous incrustations among which ants are working with all the usual energy of the ant-tribe. And these incrustations are not simply at the bottom, but come up the curves and slopes of the bowl irregularly,—half-way up perhaps in one place, while on another side they are confined quite to the lower deep. The pit is 230 feet deep, nearly circular, though after awhile the eye becomes aware of the fact that it is oblong. At the top the diameter is about 300 yards of which 250 cover what is technically called “blue,”—meaning diamondiferous soil. Near the surface and for some way down, the sides are light brown, and as blue is the recognised diamond colour you will at first suppose that no diamonds were found near the surface;—but the light brown has been in all respects the same as the blue, the colour of the soil to a certain depth having been affected by a mixture of iron. Below this everything is blue, all the constructions in the pit having been made out of some blue matter which at first sight would seem to have been carried down for the purpose. But there are other colours on the wall which give a peculiar picturesqueness to the mines. The top edge as you look at it with your back to the setting sun is red with the gravel of the upper reef, while below, in places, the beating of rain and running of water has produced peculiar hues, all of which are a delight to the eye.

As you stand at the edge you will find large high-raised boxes at your right hand and at your left, and you will see all round the margin crowds of such erections, each box being as big as a little house and higher than most of the houses in Kimberley. These are the first recipients for the stuff that is brought up out of the mine. And behind these, so that you will often find that you have walked between them, are the whims by means of which the stuff is raised, each whim being worked by two horses. Originally the operation was done by hand-windlasses which were turned by Kafirs,—and the practice is continued at some of the smaller enterprises;—but the horse whims are now so general that there is a world of them round the claim. The stuff is raised on aerial tramways,—and the method of an aerial tramway is as follows. Wires are stretched taught from the wooden boxes slanting down to the claims at the bottom,—never less than four wires for each box, two for the ascending and two for the descending bucket. As one bucket runs down empty on one set of wires, another comes up full on the other set. The ascending bucket is of course full of “blue.” The buckets were at first simply leathern bags. Now they have increased in size and importance of construction,—to half barrels and so upwards to large iron cylinders which sit easily upon wheels running in the wires as they ascend and descend and bring up their loads, half a cart load at each journey.

As this is going on round the entire circle it follows that there are wires starting everywhere from the rim and converging to a centre at the bottom, on which the buckets are always scudding through the air. They drop down and creep up not altogether noiselessly but with a gentle trembling sound which mixes itself pleasantly with the murmur from the voices below. And the wires seem to be the strings of some wonderful harp,—aerial or perhaps infernal,—from which the beholder expects that a louder twang will soon be heard. The wires are there always of course, but by some lights they are hardly visible. The mine is seen best in the afternoon and the visitor looking at it should stand with his back to the setting sun;—but as he so stands and so looks he will hardly be aware that there is a wire at all if his visit be made, say on a Saturday afternoon, when the works are stopped and the mine is mute.

When the world below is busy there are about 3,500 Kafirs at work,—some small proportion upon the reef which has to be got into order so that it shall neither tumble in, nor impede the work, nor overlay the diamondiferous soil as it still does in some places; but by far the greater number are employed in digging. Their task is to pick up the earth and shovel it into the buckets and iron receptacles. Much of it is loosened for them by blasting which is done after the Kafirs have left the mine at 6 o’clock. You look down and see the swarm of black ants busy at every hole and corner with their picks moving and shovelling the loose blue soil.

But the most peculiar phase of the mine, as you gaze into its one large pit, is the subdivision into claims and portions. Could a person see the sight without having heard any word of explanation it would be impossible, I think, to conceive the meaning of all those straight cut narrow dikes, of those mud walls all at right angles to each other, of those square separate pits, and again of those square upstanding blocks, looking like houses without doors or windows. You can see that nothing on earth was ever less level than the bottom of the bowl,—and that the black ants in traversing it, as they are always doing, go up and down almost at every step, jumping here on to a narrow wall and skipping there across a deep dividing channel as though some diabolically ingenious architect had contrived a house with 500 rooms, not one of which should be on the same floor, and to and from none of which should there be a pair of stairs or a door or a window. In addition to this it must be imagined that the architect had omitted the roof in order that the wires of the harp above described might be brought into every chamber. The house has then been furnished with picks, shovels, planks, and a few barrels, populated with its black legions, and there it is for you to look at.

At first the bottom of the bowl seems small. You know the size of it as you look,—and that it is nine acres, enough to make a moderate field,—but it looks like no more than a bowl. Gradually it becomes enormously large as your eye dwells for a while on the energetic business going on in one part, and then travels away over an infinity of subdivided claims to the work in some other portion. It seems at last to be growing under you and that soon there will be no limit to the variety of partitions on which you have to look. You will of course be anxious to descend and if you be no better than a man there is nothing to prevent you. Should you be a lady I would advise you to stay where you are. The work of going up and down is hard, everything is dirty, and the place below is not nearly so interesting as it is above. One firm at the mine, Messrs. Baring Gould, Atkins, & Co. have gone to the expense of sinking a perpendicular shaft with a tunnel below from the shaft to the mine,—so as to avoid the use of the aerial tramway; and by Mr. Gould’s kindness I descended through his shaft. Nevertheless there was some trouble in getting into the mine and when I was there the labour of clambering about from one chamber to another in that marvellously broken house was considerable

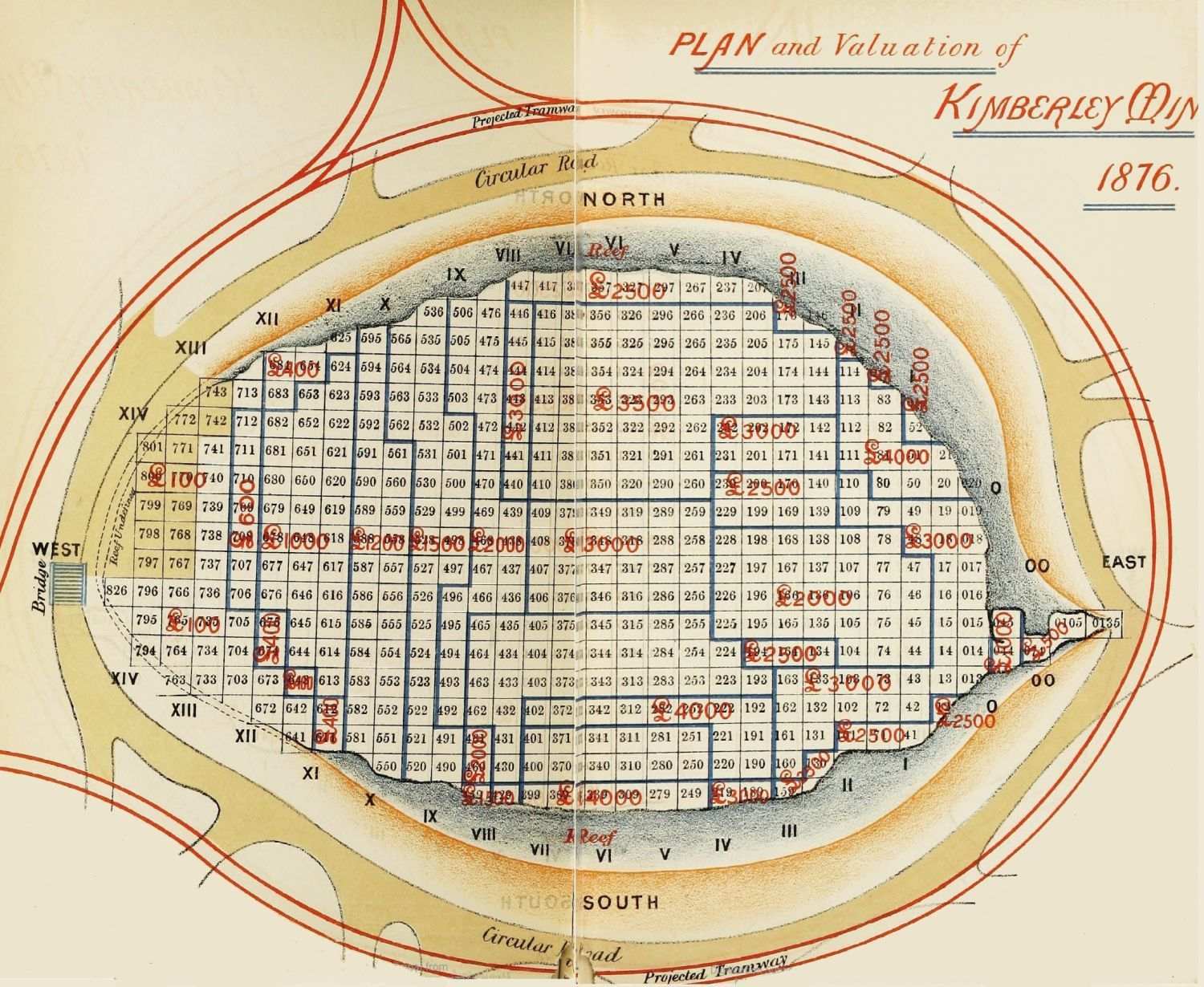

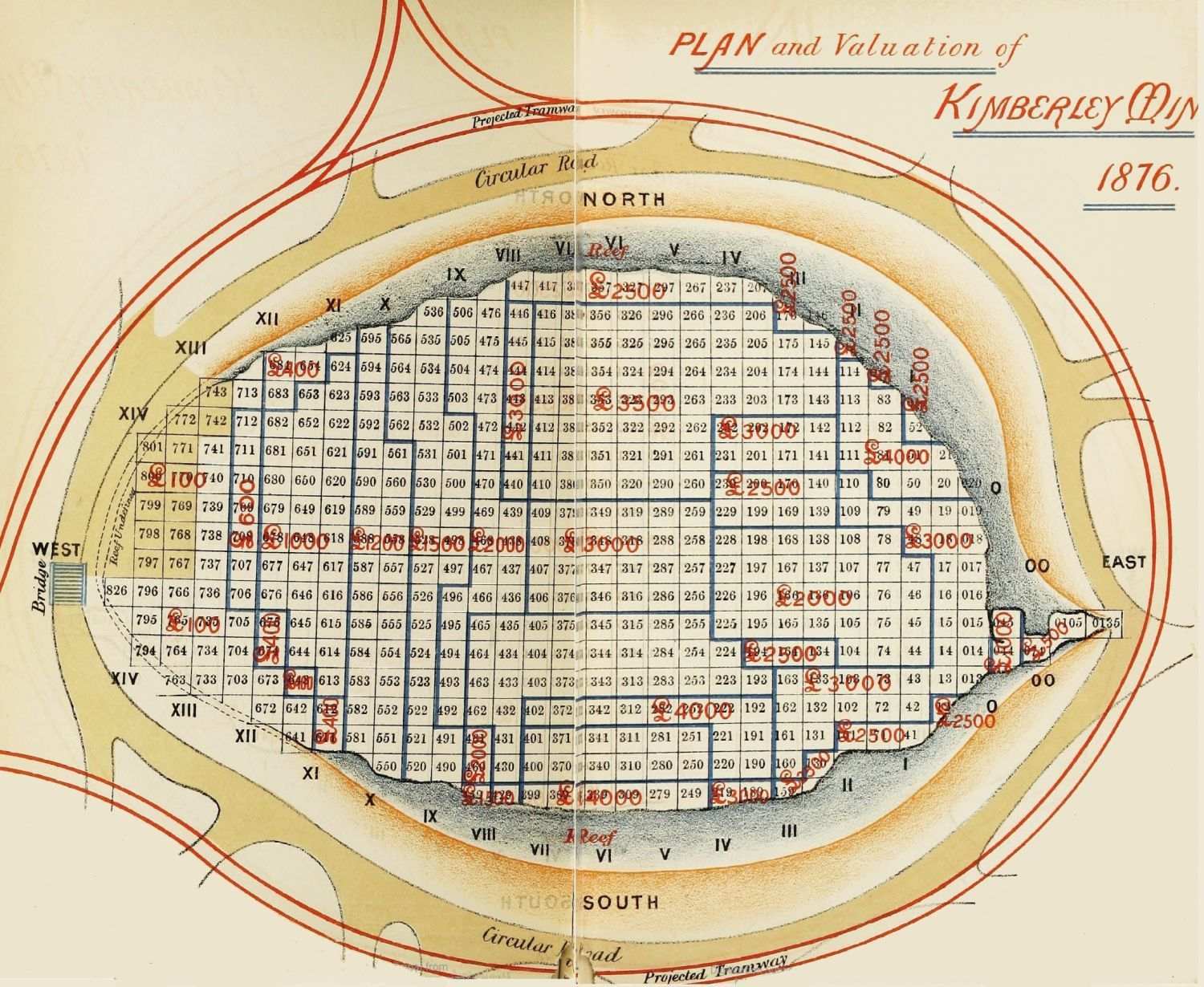

PLAN and Valuation of Kimberley Mine. 1876.

and was not lessened by the fact that the heat of the sun was about 140. The division of the claims, however, became apparent to me and I could see how one was being worked, and another left without any present digging till the claim-owner’s convenience should be suited. But there is a regulation compelling a man to work if the standing of his “blue” should become either prejudicial or dangerous to his neighbours. There is one shaft,—that belonging to the firm I have mentioned; and one tramway has been cut down by another firm through the reef and circumjacent soil so as to make an inclined plane up and down to the mine.

On looking at the accompanying plan the reader will see that the ground was originally divided into 801 claims with some few double numbers to claims at the east end of the mine;—but in truth nearly half of those have never been of value, consisting entirely of reef, the diamondiferous matter, the extent of which has now been ascertained, not having travelled so far. There are in truth 408 existing claims. The plan, which shews the locality of each claim as divided whether of worth or of no worth, shews also the rate at which they are all valued for purposes of taxation. To ascertain the rated value the reader must take any one of the sums given in red figures and multiply it by the number of subdivisions in the compartment to which those figures are attached. For instance at the west end is the lowest figure,—£100, and as there are 37 marked claims in this compartment, the rated value of the compartment is £3,700. This is the poorest side of the mine and probably but few of the claims thus marked are worked at all. The richest side of the mine is towards the south, where in one compartment there are 12 claims each rated at £5,500, so that the whole compartment is supposed to be worth £66,000. The selling value is however much higher than that at which the claims are rated for the purpose of taxation.

But though there are but 408 claims there are subdivisions in regard to property very much more minute. There are shares held by individuals as small as one-sixteenth of a claim. The total property is in fact divided into 514 portions, the amount of which of course varies extremely. Every master miner pays 10s. a month to the Government for the privilege of working whether he own a claim or only a portion of a claim. In working this the number of men employed differs very much from time to time. When I was there the mine was very full, and there were probably almost 4,000 men in it and as many more employed above on the stuff. When the “blue” has come up and been deposited in the great wooden boxes at the top it is then lowered by its own weight into carts, and carried off to the “ground” of the proprietor. Every diamond digger is obliged to have a space of ground somewhere round the town,—as near his whim as he can get it,—to which his stuff is carted and then laid out to crumble and decompose. This may occupy weeks, but the time depends on what may