Six: ARTHUR RIMBAUD

I

In the Paris of the late eighties, when men of letters met for a p’tit verre or a glass of coffee at a boulevard café, a question was often asked that had no answer but a shrug—what in heaven’s name had become of Arthur Rimbaud, the poet? The older men remembered him well, this overgrown, unmannerly whelp of eighteen who had suddenly appeared among them from some dull town in the Ardennes, and had made his way into the literary heart of things; they remembered the sensation which had followed Verlaine’s publication of his poetry.

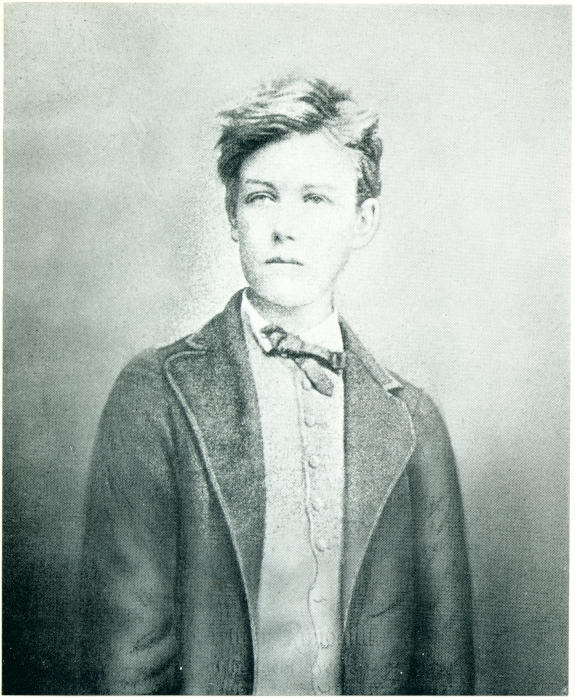

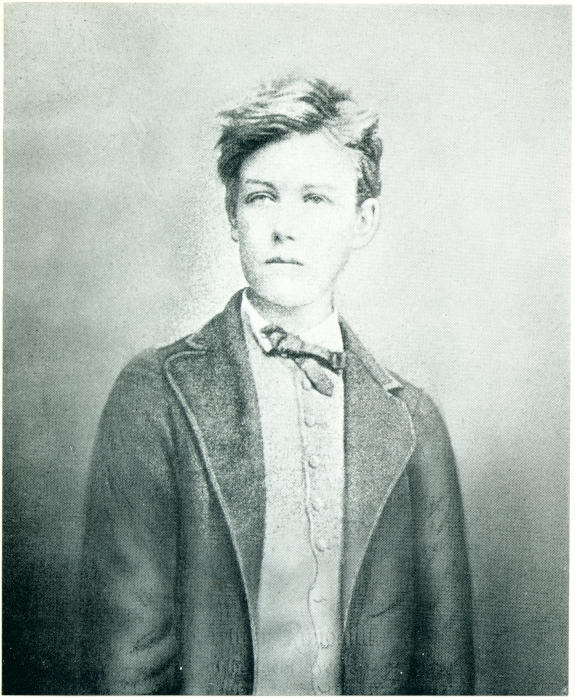

What liberties the boy had taken with the spirit and the forms of verse; the young wipe-nose-on-his-sleeve had disordered the whole world of poetry with his free rhymes, his poems in prose, his prose in poems, and his raving sonnets on the colours of vowels. “I accustomed myself,” he had said, “to direct hallucination, and managed quite easily to see a mosque where stood a factory, a school of drums kept by angels, wagons on the roads of heaven, a drawing room at the bottom of a lake; monsters and mysteries, a whole vaudeville, in fact, lifted heads of terror before me.” He had written of a day in spring, “Lying sprawled in the valley one feels that the earth is nuptial and overbrims with blood.” A strange eighteen-year-old! Some remembered the boy in his square-cut, double-breasted jacket of the seventies, his little, flat, pancake hat, pipe, and long, womanish hair hiding the back of his collar and touching his shoulders.

And now the younger generation were reading him with enthusiasm, copying his mood and manner, and annoying their elders with questions about him. Tell us of Arthur Rimbaud. Is he still alive? Did he ever actually exist? Is he simply a ghost whose name Verlaine has chosen as a pseudonym?

“Dead crazy, or king of a desert island,” said the bookish Vanier to a young student stirred by the reading of Rimbaud’s Illuminations. “On several occasions there have been rumors of his death,” said Paul Verlaine. “We can not confirm the news, and would be saddened by finding it the truth.”

ARTHUR RIMBAUD

What had become of the runaway boy from the Ardennes, the boy with the sulky mouth and hostile, insolent, and splendid eyes, the boy who ran away from home to live like a strolling ragamuffin, cheeked his elders, wrote astounding verses, and first made use of the new and alarming freedoms of modern poetry?

Had an angel suddenly descended to the boulevards of Paris, grasped a meditating literary nabob by the hair, and whisked him from his marble table and his café au lait to the burning beach of French Somaliland, the man of letters would have found a trader adding up the wriggling figures of a French account. There would not have been a book about to suggest literature; the trader was not interested in literature,—a silly business; he was interested in figures and trade like any sensible Frenchman with his life to gain. Figures, snaky French fives and sevens written down in purple ink under the Somali sun, notes about coffee and hides and firearms. The trader was M. Arthur Rimbaud. Had the nabob rushed to tell him that all young Paris was buzzing with his name, he probably would have been greeted with a rather unpleasant laugh.

No account exists in English of the mysterious last years of Rimbaud turned vagabond and African trader, for the material is difficult to assemble, and the tale has to be pieced out from notes in stray letters, reports of the Colonial office, and even the proceedings of British learned societies. Moreover, there exists no study of the purely vagabond side of his unique career.

Arthur Rimbaud was born in Charleville in French Flanders on October 20th, 1854. It is a dull industrial town in a dull region given over to a Victorian industrialism of weeds, rust, broken windows, and little brick workshops, an industrialism without any dignity of power.

His father, an army officer, having a roving disposition, and his mother “an authoritative air,” they agreed to separate, and the boy was brought up by the mother. The family was not rich exactly, yet was comfortably off in the careful French way; there were brothers and sisters for Arthur to grow up with, and things went well enough till Arthur’s fifteenth year. Then came to pass in that plain bourgeois house a situation quite without a parallel. Arthur, having grown into a lank, gawky, sulky boy with large hands and a provincial twang to his speech, began to develop into a genius with the ripened intellect of an adult, and this sulky child with the amazing grown-up mind remained subject to the purse strings and parental direction of a common-place, ill-educated, middle-aged woman who lacked acuteness of mind to see the change.

Much has been written of Mme. Rimbaud’s “domination” of the prodigy, and its effect on the boy’s mind. Yet the mother does not appear to have been unduly harsh or unfeeling; she simply was incapable of understanding the mind of her son. Moreover, she was not without that sense of terror and exasperation which consumes parents who find the children of their flesh developing alien minds and alien ways.

From so grotesque and abnormal a situation, the boy on whom genius had descended, escaped by running away. He accompanied his mother and sisters for a walk, pretended to wish to go home to get a book, and disappeared.

This first vagabondage, undertaken in the disordered war-year of 1870, landed him in the jail for strays and political suspects at Mazas. His one understanding friend, the young schoolmaster Izambard, then rescued him, and sent him back to his mother. Mme. Rimbaud was naturally quite upset. “I fear the little fool will get himself arrested a second time,” she wrote to Izambard; “he need never then return, for I swear that never in my life should I ever receive him again. How is it possible to understand the foolishness of the child, he who is so good and quiet ordinarily?”

She did not want her Arthur to be a vagabond. The word has a far different connotation in French than it has in English. In English, it has acquired something of a poetic flavour; in French it is still decidedly a term of reproach. The French, who plan their lives and their children’s lives with a minuteness Englishmen and Americans can never understand, see nothing romantic in a high road wanderer without a definite place in life or a definite goal. The sense of the definite goal is keen in France.

Imagine, then, the anger and despair of Mme. Rimbaud, good Frenchwoman that she was, when her sixteen-year-old genius took to sleeping in barns and following the road. She felt the same way about it an English mother might feel about a son’s inclination to take spoons. There is still another element in the relation of Arthur and his mother which escapes the English or American student of Rimbaud’s life, and that is the supreme place of the parent in the hierarchy of the French family. Arthur’s escapades were a blow to Mme. Rimbaud’s authority and prestige; in the eyes of the French neighbourhood Arthur’s vagabondage shamed the mother as well as the son.

After his first return, the boy endured the old, impossible situation for a week, and then fled once more from Charleville. Brussels sees him, and Paris, a boy with worn, dusty clothes staring into the windows of bookshops. At Paris he joined the Communist army for a while. Having been given no uniform, he escaped the general massacre of the insurrectionary troops, and went eastward over the road to Rheims and Château-Thierry. He had no money, but he had youth, his dreams, and a colossal impudence. On occasion he would invade houses while the owners were away in the fields, and go to bed in the best bed. The manœuvre was not always as successful as the boy might have hoped.

There rises before the mind’s eye a picture of the gawky, impudent, runaway stripling with the insolent eyes trudging the white roads of France with their fine, sharp surface dust and underbody hard and relentless as a ribbon of solid stone; one sees him pass the haycocks in the fields, the yellow-green of river meadows, the opaque, greenish streams, the poplars, and village chimneys curling up wood smoke into the rosy, humid dawn.

The boy enjoyed the bohemian adventure, and found a place in his mind for its sordid side.

Through 1870 and most of 1871 he comes and goes; he writes, he sulks, he listens to impressive lectures about the heavy necessity of beginning to think of a profession or a career. Arthur, sulkily imprisoned in his abominated Charleville,—“my native town leads in imbecility among small provincial towns”—had a horror of dull labour. He saw too much of it about him. “Masters and workmen, yokels all of them, all ignoble. The hand with the pen is worth the hand with the plough. What a century of hands!” Said Verlaine, “He had a high disdain for whatever he did not wish to do or be.”

Presently comes the great change and the first real opportunity. He sends a sheaf of poems to Paul Verlaine, and Verlaine replies inviting him to be his guest in Paris.

From an abnormal situation the boy thus advanced to an absurd one. The Verlaines were poor, and the poet and his seventeen-year-old wife were living with the wife’s parents in order to save money. They may have been prepared for the coming of a young man, even a very young man, but this gawky, queer, unmanageable seventeen-year-old boy...! It is clear that he soon came to be regarded as an inconvenient intruder by the practical ladies of the poet’s family.

In spite of his difficulties, many of his own making, the year 1871-’72 was Rimbaud’s great year. He perfected his theory that the maker of poetry should be a seer, and practise “the long, immense, and reasoned disordering of the senses,” and give to the world “the supreme exaltation arrived at through things unheard of and unnameable.” The Parisian literary world, not knowing what to make of art so disorderly and personal, Rimbaud took his familiar refuge in rudeness. A consciousness of his genius strengthened the wings of his pride. In odds and ends of time, in order to gain a little money, he hawked key rings under the arcades of the Rue de Rivoli. Paris beginning to bore him, he actually returned for a little time to Charleville.

While Rimbaud was at Charleville, Verlaine, beset by family troubles, wrote to him begging him to join him in a vagabond tour. Rimbaud, whose consciousness was melting in the flame of hallucinations and poetic ecstasies, accepted at once, and in July, 1872, the two poets set off together. “I sought the sea, as if it were to cleanse me from a stain,” wrote Rimbaud. A curious pair and a curious pilgrimage. One has a glimpse of mean lodgings, gutters, roadsides, empty pockets, visions, exaltations, absinthe, dirt and debt. From Belgium, they went to England, where each gathered a few pence teaching French. Returning to Brussels in July, 1873, Verlaine, while in some kind of mental state best studied by psychopathologists, shot his fellow poet in the wrist with a pistol, and was promptly imprisoned by the Belgian authorities. The wound was not serious.

Mme. Rimbaud owned a kind of farm and country house at Roche, and later in the same month of July she suddenly saw Arthur coming towards the gate with his arm in a sling. Now comes a problem to be answered by those who study genius; Rimbaud ceased writing poetry forever. The verse which was to stir France and mould a world style was thus the work of a boy in his eighteenth year. What had taken place? Had his capricious genius flown away to another bough? Had his poetry of visions and hallucinations begun to uncover mysteries beyond the power of the human spirit to endure? Had some intense satisfaction he had known in the composition of poetry begun to fade?

Such is the tale of Arthur Rimbaud’s bizarre career as a poet. Is it a wonder that the younger generation wished to know what had become of the man?

II

The poet having ceased to write poetry, a vast part of the house of the brain now lay dark and tenantless, its emptiness accentuated by a memory of the lost spirit whose poetic vitality had once filled the mansion. A wildness of wandering now seized the boy; he was trying to fill the haunted, echoing rooms as best he could, and like the king in the parable, he sought his guests on the roads. He goes to Stuttgart to study German; he crosses the St. Gothard pass on foot and visits Italy; he pays his lodging with casual labor as he goes. And always searching, searching, searching with growing exasperation in his tone.

Then Charleville, and a winter picking up Arabian and Russian,—he is trying to house the intellect in a room once inhabited by something of the very essence of the spirit,—then a journey through Belgium and Holland, and a meeting with a Dutch recruiting sergeant who persuaded him to join the Dutch colonial army. On May 19th, 1876, he signs an engagement for six years, receives 600 francs as a gratuity, sails for Java, disembarks at Batavia, serves for three weeks, deserts, and returns to Europe on an English ship.

Returning to Charleville, he remained there but a short time, and then hurried to Cologne. A strange new guest had arrived unsought in his mind’s house, the money-saving instinct, for it is deeper than reason, of the provident French mind. Its first manifestation was not exactly a sympathetic one; in fact, the poet’s part in it has a sniff of the bounder, Latin style. Envying the easy commissions of the sergeant who had enlisted him, this deserter so loudly sang the praises of the Dutch Colonial army that he induced a dozen young Germans to accompany him to Holland and enlist. Rimbaud then pocketed the enlistment commission, and escaped to Hamburg.

At Hamburg a circus is in need of an interpreter, and the sometime poet of hallucinations is given the post. With the circus he goes to Copenhagen, and then flies from it to Stockholm.

The winter of ’78 and ’79 found him in the isle of Cyprus as foreman of a quarry. The work proved unhealthy, Rimbaud caught typhoid, and in the summer of 1879 he wandered home to recover. His friend Delahaye, finding him at the farm of Roche, ventured to ask him if he still had an interest in literature. Rimbaud shook his head with a smile, as if his thoughts had suddenly turned to something childish, and answered quietly, “I no longer concern myself with it.”

In the spring of 1880, the poet being then twenty-six years old, he returned to Africa and the East, there to spend his last eleven years.

In August, 1880, he was at Aden on the Red Sea, as an employee of the French trading house of Mazaran, Viannay and Bardey. The town is one of the most singular and utterly terrible places of the earth.

“You could never come to imagine the place,” wrote Rimbaud. “There is not a single tree, not even a shrivelled one, not a single blade of grass, not a rod of earth, not a drop of fresh water. Aden lies in the crater of an extinct volcano which the sea has filled with sand. One sees and touches only lava and sand incapable of sustaining the tiniest spear of vegetation. The surrounding country is an arid desolation of sand. The sides of the crater prevent the entry of any wind, and we bake at the bottom of the hole as if in a lime kiln. One must be indeed a victim of circumstance to seek employment in such hells!”

The house by which Rimbaud was employed traded in Abyssinian ivory, musk, coffee, and gold, and their Abyssinian station was at Harrar. Rimbaud having developed a marvellous facility for native languages, he was presently put in charge of the Abyssinian branch. Harrar stood on an elevation, and the climate was fair enough, though in the spring rains it was often damp and cold. The poet wandered about fearlessly, buying gums and ostrich plumes. It was a busy, confused, uncertain career, and Rimbaud wrote of it with a snarl. Here he was, buried in a world of natives, and “obliged to talk their gibberish languages, to eat their filthy dishes, and undergo a thousand worries rising from their laziness, their treachery, and their stupidity. And this is not the worst of it; there is the fear of becoming animalized oneself, isolated as remote as one is from all intellectual companionship.”

The month of July, 1884, saw the house of Mazaran, Viannay and Bardey vanish from the scene, and emerge as the property of Bardey. In October, 1885, the poet’s contract with this new Maison Bardey expired, and he refused to renew it after a “violent scene.” He had spent five years as a trading agent in Arabia and Abyssinia; he knew the country and its languages as did no other European, and he thought it time to go into business for himself. At Aden dwelt another French agent, one Pierre Labutut, and with this man Rimbaud presently founded a new company.

Old Menelik of Abyssinia wanted guns; he paid fancy prices for rifles, and Rimbaud and Labutut determined to run in rifles on a grand scale. They would secure rifles of a disused model in Europe, ship them to Aden, transfer them to a caravan gathered at Tadjourah on the Somali coast, and then take them to Choa, and sell them to Menelik. At Liége in Belgium or at French military depots, old rifles might be had at seven or eight francs apiece; they would sell them to Menelik for forty francs and the freight.

It was a difficult and complicated task. There were a thousand things to be thought of—provisions, salaries, camel hire, extortions, tips, taxes, impositions, buying and maintenance. The caravan would have to spend fifty days in a “desert country” among unfriendly tribes.

“The natives along the caravan route are Dankalis,” said Rimbaud; “they are Bedouin shepherds and Moslem fanatics and they are to be feared. It is true that we are armed with rifles while the Bedouins have only lances. Nevertheless, all caravans are attacked.”

A difficulty with the French foreign office over the matter of gun running now intervened, and then came a serious blow. Labutut died, deeply in debt, and leaving the weight of the whole complicated enterprise on Rimbaud’s shoulders. In spite of these checks, however, the poet went ahead with his scheme and led his caravan to Choa.

The caravan arrived, but the scheme was a failure. “My venture has taken the wrong turn,” wrote Arthur to Bardey. The huge expenses had not only eaten up all the expected profits, but had even consumed the little sum Arthur had managed to amass in the previous years. Yet he paid all Labutut’s debts and gave a sum to his partner’s young son. “His very generous and discreet charity,” said Bardey, “was probably one of the very few things he did without snarling or shrill complaints.”

Then to Cairo with what money he has in a money belt about him. He “cannot” return to Europe because he would certainly die in the cold winter, he is too accustomed to a “wandering, free and open life” and because he has “no position.” That French touch at the end! Presently he re-establishes himself at Harrar, and manages to gain a modest living. One sees him at his little trading station cautiously receiving small shipments of rifles, weighing coffee in scales, and estimating the worth of his ivory,—a lean, sun-browned French trader in his early thirties. In 1889 he received a letter which must have put a strange look on his face. It was from a Parisian journalist.

“Sir,” it ran, “living so far away from us, you are doubtless unaware that in a very small group at Paris, you have become a legendary personage. Literary reviews of the Latin quarter have published you, and your first efforts have even been gathered into a book.”

In 1891 an infection of the knee obliged him to return to Europe, an operation failed to check the malady, and in November he found that timelessness which he once pictured as “the sea fled with the sun.”

As a personage, Rimbaud remains the most mysterious of all vagabonds. The ceaseless, embittered, eager search for something that was his life,—what shall be its last interpretation? Did he seek something which had fled him, or something to replace the thing which had fled? From the Latin quarter of the 80’s, with its book shops, its old dank houses, and drizzling rain of the cloudy Parisian spring to the lifeless oven of Aden, his mind had known but one aim, and that an aim unlike any other sought by the great vagabonds. No answer may be found by scanning the poetry, for Rimbaud the poet and Rimbaud the Somali trader were two men. Active, nervous, intellectual, difficult and often utterly unpleasant and unsympathetic, he wanders about his bales of goods in the warehouse shadows, a mysterious and intriguing figure. After all, though he did not find the answer he sought—who does?—he found activity, and for him activity was the soul’s rest.