CHAPTER IV

IN THE CELLARS

We were soon recalled from our reflections; for Mother Prioress, emerging from the parlour, announced to us that we were to have visitors that night. Two priests and five ladies had begged to be allowed to come to sleep in our cellars, as news had been brought that the Germans might penetrate into the town that very evening. One could not refuse at such a moment, though the idea was a novel one—enclosed nuns taking in strangers for the night. But in the face of such imminent peril, and in a case of life or death, there was no room for hesitation. So to work we set, preparing one cellar for the priests, and another for the ladies. In the midst of dragging down carpets, arm-chairs, mattresses, the news soon spread that there was word from Poperinghe. We all crowded round Mother Prioress in the cellar, where, by the light of a little lamp, she endeavoured in vain to decipher a letter which Dame Placid had hurriedly scribbled in pencil, before the driver left to return to Ypres. The picture was worth painting! Potatoes on one side, mattresses and bolsters on the other—a carpet half unrolled—each of us trying to peep over the other’s shoulder, and to come as near as possible to catch every word. But alas! these latter were few in number and not reassuring. ‘We can only get one room for Lady Abbess.... Everywhere full up.... We are standing shivering in the rain.... Please send ——’ Then followed a list of things which were wanting. Poor Lady Abbess! Poor Dame Josephine! What was to be done? Mother Prioress consoled us by telling us she would send the carriage back the first thing next morning to see how everyone was, and to take all that was required. We then finished off our work as quickly as possible, and retired to our own cellar to say compline and matins; for it was already 10 o’clock. After this we lay down on our ‘straw-sacks’—no one undressed. Even our ‘refugees’ had brought their packages with them, in case we should have to fly during the night. Contrary to all expectations, everything remained quiet—even the guns seemed to sleep. Was it a good or evil omen? Time would show.

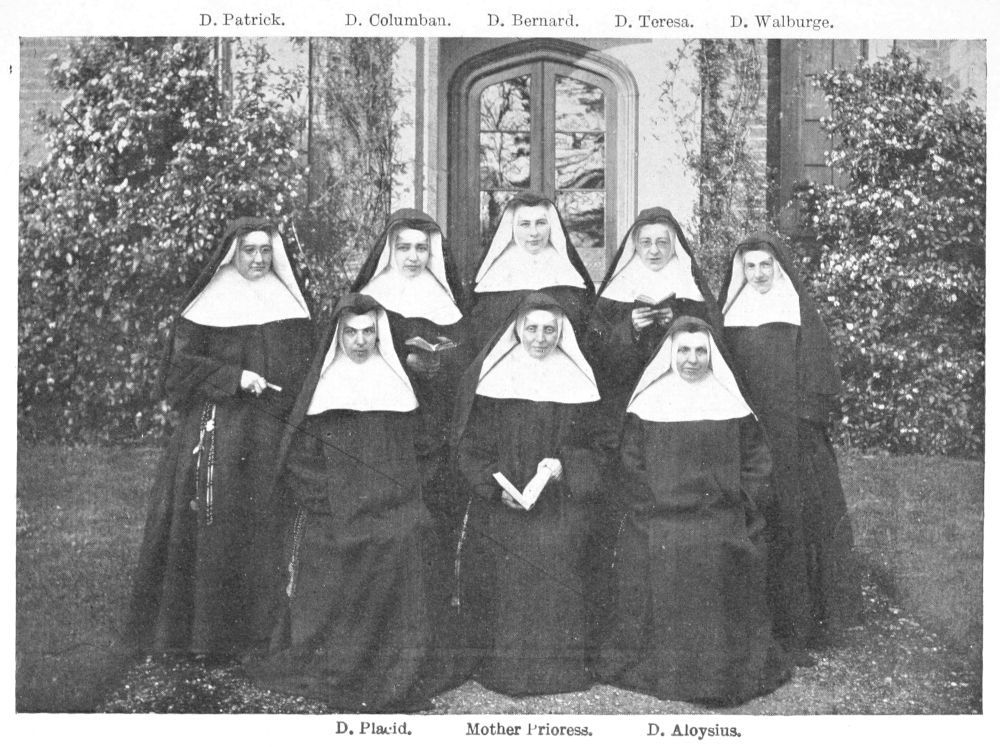

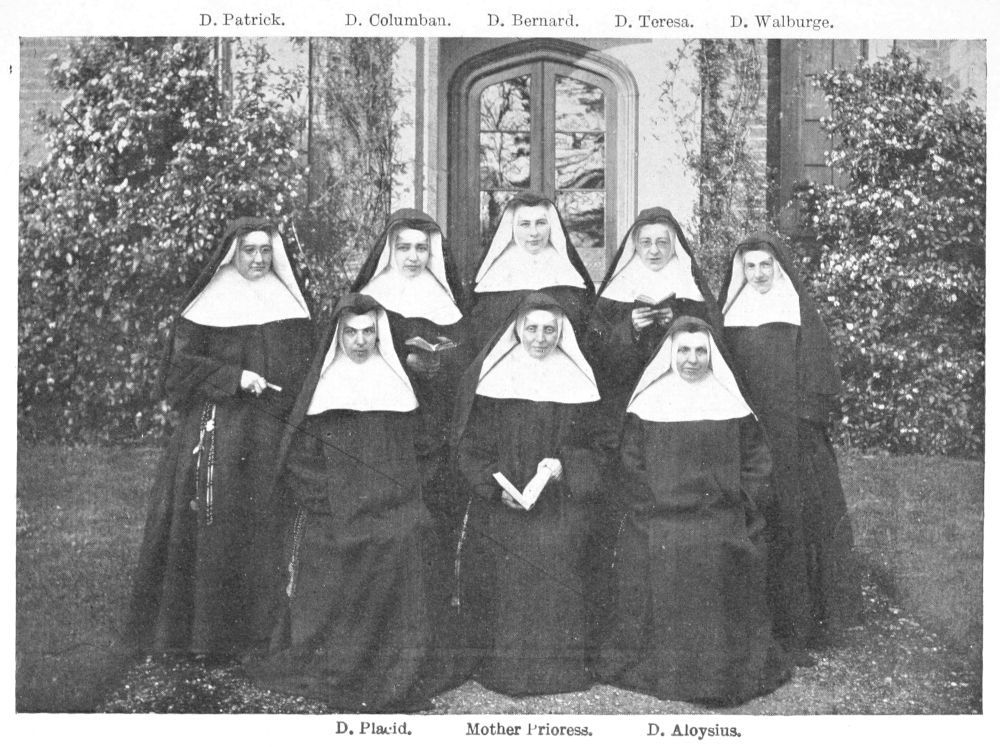

D. Patrick. D. Columban. D. Bernard. D. Teresa. D. Walburge.

D. Placid. Mother Prioress. D. Aloysius.

THE IRISH DAMES OF YPRES.

At 5 o’clock next morning the alarm-clock aroused the community, instead of the well-known sound of the bell. There was no need, either, of the accustomed ‘Domine, labia mea aperies’ at each cell door. At 5.30, we repaired to the choir as usual for meditation, and at 6 recited lauds—prime and tierce. At 7, the conventual Mass began; when, as though they had heard the long-silent bell, the guns growled out, like some caged lion, angry at being disturbed from its night’s rest. The signal given, the battle waged fiercer than before, and the rattling windows, together with the noise resounding through the church and choir, told that the silence of the night had been the result of some tactics of the Germans, who had repulsed the Allies. Day of desolation, greater than we had before experienced! Not because the enemy was nearer, not because we were in more danger, but because, at the end of Holy Mass, we found ourselves deprived of what, up till then, had been our sole consolation in our anguish and woe. The sacred species had been consumed—the tabernacle was empty. The sanctuary lamp was extinguished. The fear of desecration had prompted this measure of prudence, and henceforth our daily Communion would be the only source of consolation, from which we should have to derive the courage and strength we so much needed.

The Germans nearer meant greater danger; so, with still more ardour, we set to work, especially as we were now still more reduced in numbers. The question suddenly arose, ‘Who was to prepare the dinner?’ Our cook, as has already been said, had been one of the three German Sisters who had left us on September 8; subsequently, Sister Magdalen had replaced her, and she, too, now was gone. After mature deliberation, Dame Columban was named to fulfil that important function. But another puzzle presented itself—What were we to eat? For weeks, no one had seen an egg! Now, no milk could be got. Fish was out of the question—there was no one left to fish. To complete the misery, no bread arrived, for our baker had left the town. Nothing remained but to make some small loaves of meal, and whatever else we could manage—with potatoes, oatmeal, rice, and butter (of which the supply was still ample), adding apples and pears in abundance. Edmund was sent out to see if he could find anything in the town. He returned with four packets of Quaker oats, saying that that was all he could find, but that we could still have a hundred salted herrings if we wished to send for them.

We had just begun the cooking, when the tinkling of the little bell called everyone together, only to hear that a German Taube was sailing just over the Abbey; so we were all ordered down to the cellars, but before we reached them there was crack! crack! bang! bang! and the rifle-shots flew up, from the street outside the convent, to salute the unwelcome visitor. But to no purpose, and soon the sinister whistling whirr of a descending projectile grated on our ears, while, with a loud crash, the bomb fell on some unfortunate building. We had at first been rather amused at this strange descent to our modern catacombs; but we soon changed our mirth to prayer, and aspiration followed aspiration, till the ceasing of the firing told us that the enemy was gone. We then emerged from the darkness, for we had hidden in the excavation under the steps leading up to the entrance of the Monastery, as the surest place of refuge, there being no windows. This was repeated five or six times a day; so we brought some work to the cellars to occupy us. The firing having begun next morning before breakfast was well finished, one sister arrived down with tea and bread and butter. Later on, while we were preparing some biscuits, the firing started again; so we brought down the mixing-bowl, ingredients and all. We continued our work and prayers and paid no more attention to the bombs or the rifle-shots.

Our dear Lady Abbess was not forgotten. The next day Mother Prioress sent for the carriage, while we all breathed a fervent ‘Deo gratias’ that our aged Abbess was out of danger; for what would she have done in the midst of all the bombs? Owing to the panic, which was now at its height, all the inhabitants who were able were leaving the town, abandoning their houses, property—all, all—anxious only to save their lives. There was no means of finding a carriage.

Our life, by this time, had become still more like that of the Christians of the first era of the Church, our cellars taking the place of the catacombs, to which they bore some resemblance. We recited the Divine Office in the provision cellar under the kitchen, which we had first intended for Lady Abbess. A crucifix and statue of Our Lady replaced the altar. On the left were huge wooden cases filled with potatoes, and one small one of turnips—on the right, a cistern of water, with a big block for cutting meat (we had carefully hidden the hatchet, in case the Germans, seeing the two together, should be inspired to chop off our heads). Behind us, other cases were filled with boxes and sundry things, whilst on top of them were the bread-bins. We were, however, too much taken up with the danger we were in to be distracted by our surroundings. We realised then, to the full, the weakness of man’s feeble efforts, and how true it is that God alone is able to protect those who put their trust in Him. The cellar adjoining, leading up to the kitchen, was designed for the refectory. In it were the butter-tubs, the big meat-safe, the now empty jars for the milk. A long narrow table was placed down the centre, with our serviettes, knives, spoons, and forks; while everyone tried to take as little space as possible, so as to leave room for her neighbour. The procession to dinner and supper was rather longer than usual, leading from the ante-choir through the kitchen, scullery, down the cellar stairs, and it was no light work carrying down all the ‘portions,’ continually running up and down the steps, with the evident danger of arriving at the bottom quicker than one wanted to, sending plates and dishes in advance.

Time was passing away, we now had to strip the altar—to put away the throne and tabernacle. Some one suggested placing the tabernacle in the ground, using a very large iron boiler to keep out the damp, and thus prevent it from being spoilt. This plan, however, did not succeed, as will be seen. Dame Teresa and Dame Bernard flew off to enlarge the pit they had already begun, watching all the time for any Taube which might by chance drop a bomb on their heads, and, indeed, more than once, they were obliged to take refuge in the Abbey. Strange to say, these things took place on Sunday, the Feast of All Saints. It was rather hard work for a holiday of obligation, but we obtained the necessary authorisation. Towards evening the hole was finished and the boiler placed in readiness. But how lift the throne, which took four men to carry as far as the inner sacristy? First we thought of getting some workmen, but were any still in the town? No, we must do it ourselves. So, climbing up, we gradually managed to slip the throne off the tabernacle, having taken out the altar-stone. We then got down; and whether the angels, spreading their wings underneath, took part of the weight away or not, we carried it quite easily to the choir, where, resting it on the floor, we enveloped the whole in a blanket which we covered again with a sheet. The tabernacle was next taken in the same manner, and, reciting the ‘Adoremus,’ ‘Laudate,’ ‘Adoro Te,’ we passed with our precious load through the cloisters into the garden. It was a lovely moonlight night, and our little procession, winding its way through the garden paths, reminded us of the Levites carrying away the tabernacle, when attacked by the Philistines. We soon came to the place, where the two ‘Royal Engineers’—for so they had styled themselves (Dame Teresa and Dame Bernard)—were putting all their strength into breaking an iron bar in two, a task which they were forced to abandon. We reverently placed our burden on the edge of the cauldron, but found it was too small. Almost pleased at the failure, we once more shouldered the tabernacle, raising our eyes instinctively to the dark blue sky, where the pale autumn moon shone so brightly, and the cry of ‘Pulchra ut luna’ escaped from our lips, as our hearts invoked the aid of Her, who was truly the tabernacle of the Most High. As we gazed upwards, where the first bright stars glittered among the small fleecy clouds, wondering at the contrast of the quiet beauty of the heavens and the bloodshed and carnage on earth, a strange cloud, unlike its smaller brethren, passed slowly on. It attracted our attention. In all probability it was formed by some German shell which had burst in the air and produced the vapour and smoke which, as we looked, passed gradually away. We then re-formed our procession and deposited the tabernacle in the chapter-house for the night. Needless to say, it takes less time to relate all this than it did to do it, and numberless were the cuts, blows, scrapes, and scratches, which we received during those hours of true ‘hard labour’; but we were in time of war, and war meant suffering, so we paid no attention to our bruises.

Our fruitless enquiries for a means to get news of Lady Abbess were at last crowned with success. Hélène, the poor girl of whom mention has been already made, and who now received food and help from the monastery, came, on Sunday afternoon, to say that two of her brothers had offered to walk to Poperinghe next day, and would take whatever we wished to send. After matins, Mother Prioress made up two big parcels, putting in all that she could possibly think of which might give pleasure to the absent ones. The next day was spent in expectation of the news we should hear when the young men returned.

Breakfast was not yet finished, when the portress came in with a tale of woe. One of our workmen was in the parlour, begging for help. During the night a bomb had been thrown on the house next to his; and he was so terrified that, not daring to remain in his own house any more, he had come with his wife and four little children to ask a lodging in our cellars. For a moment Reverend Mother hesitated; but her kind heart was too moved to refuse, and so the whole family went down into the cellar underneath the class-room, which was separated from the rest, and there remained as happy as could be. We were soon to feel the truth of the saying of the gospel, ‘What you give to the least of My little ones, you give it unto Me.’

In the afternoon, we heard that the cab-driver, who had been to the convent on Friday, had spread the news that he had been ordered to Poperinghe the next day, to bring back the Lady Abbess and nuns. What had happened? Could they not remain in their lodgings? Did they think that the bombardment had stopped—just when it was raging more fiercely than ever—when, every day, we thought we should be obliged to flee ourselves? They must be stopped—but how? Hélène, who was again sent for, came announcing her two brothers’ return. Mother Prioress asked if it would be too much for them to go back to Poperinghe to stop Lady Abbess from returning. They, however, declared they would never undertake it again, the danger being too great, and it being impossible to advance among the soldiers. Mother Prioress then determined to go herself, asking Hélène if she would be afraid to go with her to show the way. Hélène bravely replied that she was not afraid and would willingly accompany Mother Prioress. As usual, Mother Prioress would allow none of us to endanger our lives. She would go herself—and on foot, as the price demanded for the only carriage available was no less than 40 francs. In vain we begged her to let one of us go. It was to no purpose; and on Tuesday morning she started off, accompanied by Hélène, leaving the community in a state of anxiety impossible to describe. ‘Would she be able to walk so far?’ we asked ourselves. ‘What if a bomb or shell were to burst on the road?’ ‘Would she not probably miss Lady Abbess’ carriage?’ We were now truly orphans, deprived both of our Abbess and our Prioress, and not knowing what might happen to either of them. After an earnest ‘Sub tuum’ and ‘Angeli, Archangeli,’ we went about our different tasks; for we had promised Reverend Mother to be doubly fervent in her absence. At 11 o’clock we said the office and afterwards sat down to dinner, for which no one felt the least inclined. The latter was not yet finished, when there was a ring at the door-bell, and in a few moments our Prioress stood before us. We could hardly believe our eyes. She then related her adventures which, for more accuracy, I give from her own notes:—

‘When I heard the door shutting behind me, and the key turning in the lock, in spite of all my efforts, the tears came to my eyes. I was then really out of the enclosure—back again in the world—after twenty-seven years spent in peaceful solitude. The very sight of the steps brought back the memory of the day when I mounted them to enter the Monastery. I hesitated.... There was still only the door between us, but no! my duty lay before me. I must prevent Lady Abbess returning; so, taking courage, I started off with Hélène, who was trying all she could to console me. I followed her blindly. As we advanced, the traffic increased more and more. Motor-cars, cavalry, foot-soldiers, cyclists, passed in rapid succession. On the pavement, crowds of fugitives blocked the passage. Old and young, rich and poor, alike were flying, taking only a few small packets with them—their only possessions. Mothers, distracted with grief, led their little ones by the hand, while the children chattered away, little knowing the misery which perhaps awaited them. And the soldiers! they never ceased. The Allies, in their different uniforms, passed and repassed in one continued stream, while the motor-cars and bicycles deftly wended their way between soldiers and civilians. I was stupefied, and thought at every moment we should be run over; but my companion, amused at my astonishment, assured me there was nothing to fear. We had called on the burgomaster for our passports; but he was absent, and we had been obliged to go to the town hall. After that, I called on M. le Principal du Collège Episcopal, our chaplain, to state that it was impossible to obtain a carriage (as I had arranged with him that morning), owing to our poverty, and that I should therefore be obliged to go on foot. He approved of our undertaking, and even advised me to take the whole community straight away to Poperinghe. I told him I must first prevent Lady Abbess from coming back; but that, once at Poperinghe, I intended certainly to look out for a convent which would receive us all. The British ambulance was established in the college, and it seemed really like barracks.

‘Once in the street again, I heard, click! clack!! the British soldiers were shooting at a German Taube passing over the town. We hastened on. Many houses were already empty—nearly all the shops were closed. Here and there a heap of ruins showed where a shell had made its way, while out of the broken windows, the curtains blowing in the wind showed the remains of what had once been sumptuous apartments. We soon left the station behind us, and continued on the main road, with here and there a few houses which seemed more safe by being out of the town; yet some of them had also been struck. The regiments filled the road more numerously than ever, while the unfortunate fugitives, with a look of terror on their pale faces, fled from the doomed city. Some, who had left days before, were venturing back again in the hope of finding their homes still untouched. We continued our way, stopped now and then by some unfortunate creature, asking where we were going, and relating in return his story of woe. Suddenly I heard myself called by name. “Dame Maura! Yes, it is really she!” and, at the same moment, Marie Tack (an old pupil) flew into my arms. Her brother, who accompanied her, now came forward, and took great interest in everything concerning the convent. “Well!” he said, “we are benefactors of the Carmelites at Poperinghe—my brother even gave them their house. Say that it is I who have sent you, and you will surely be well received.” I thanked him for his kindness and we parted, they returning to Ypres, where they had not dared to sleep. In my heart I sent a grateful aspiration towards the Divine Providence of God, which thus gave me this little ray of hope. Meanwhile, the parcels we were carrying began to weigh more and more heavily on us. We helped each other as best we could, as I saw that poor Hélène was almost out of breath, having taken the heaviest for herself. The roads also were very bad, and we could hardly advance owing to the mud. At length, after walking two hours, we saw the steeple of Vlamertinghe in the distance. It was time, for I felt I could not go farther. I remembered that Louise Veys (another old pupil) lived at Vlamertinghe, though I had forgotten the address. I asked several people in the streets if they could direct me, but I received always the same answer: “I am sorry not to be able to oblige you, Sister. I am a stranger, I come from Ypres—from Roulers—from Zonnebeke.” At last, I ventured to ring at the door of one of the houses. It happened to be the very one I was looking for. Louise, who was at the ambulance, came running to meet me, with Mariette and Germaine Tyberghein, and Marie-Paule Vander Meersch. The latter told me that the church of their village, Langemarck, was burnt, and she feared that their house, which was close by, would have met with the same fate. At this moment, her sister Claire, who had remained with the wounded soldiers, came running in, crying out: “Lady Abbess is here, and Dame Josephine.”—“Where?” I exclaimed. Instead of answering, she took me by the hand, and we both ran out to where a cab was standing. I flew to the door, and was soon in Lady Abbess’ arms. I could hardly restrain my tears. How was it then that the carriage on its way from Poperinghe to Ypres had stopped just in front of the Veys’ house, when neither the driver nor anyone else knew to whom it belonged, or still less that I was there? Once again Divine Providence had come to our help, otherwise we should have missed each other. The cabman, who had innocently been the means of our happy meeting, by stopping to get refreshments, now appeared. I explained that it was an act of the greatest imprudence to conduct Lady Abbess to Ypres; but he would listen to nothing—meaning to go. He declared the danger was far greater at Poperinghe, and then drove away with Mother Abbess to Ypres, leaving me in consternation. Mariette and Germaine Tyberghein offered me their carriage, to return to Ypres. It was soon ready, and we started back once more. Half-way to Ypres, we saw the other cab again stationary, and a British officer talking to the nuns through the window. We called out to our coachman to stop, knocking at the window with might and main. All was useless. The noise of the innumerable horses, provision and ammunition carts, passing, deafened him, and he continued peacefully, quite unaware that anything had happened. When we arrived at Ypres, the Germans were shelling it in real earnest. I wished to go back again, to stop Lady Abbess at any price, but was not allowed. They said no one would be permitted to come into the town, and that the other cab would probably have been sent back.’

This day was not to pass without another surprise; for what was our astonishment, at about eight o’clock, to see Dame Placid once more in our midst! The officer whom Mother Prioress had seen talking through the carriage-window, had said that on no account could Lady Abbess think of going on to Ypres, which was actually being bombarded. The cab had thereupon gone back to Poperinghe; but Dame Placid had alighted, and come to Ypres on foot. We crowded round her to get news of all that had happened during the last four days, which seemed like four weeks. After we had related all that had passed in the Monastery since her departure, Dame Placid told us in return what she had gone through. On the Friday afternoon, when our poor refugees had driven to Poperinghe, they went straight to the Benedictine Convent, making sure they would be received without any difficulty. But alas! the Monastery was full of soldiers, and no less than fifty other fugitives were waiting at the door. From there, they drove to the Sœurs Polains where, also, every corner was taken up—then they went on to a private house, but always with the same result, until at last some one directed them to La Sainte Union, where they found a lodging. It had been pouring rain the whole time, and they were all cramped and cold. Poor Lady Abbess missed so much the little comforts she had had at the Abbey, and finally resolved to return to Ypres, with the result we know.

What could we now do to help her? It was decided that Sister Romana should go back with Dame Placid to see if she could not be of use. The two fugitives left at about 4 o’clock, pushing before them a kind of bath-chair filled with packets and parcels for Lady Abbess and the old nuns. A rather strange equipment, which was doomed never to reach its destination. Having, with the greatest difficulty—owing to the condition of the roads—arrived at Vlamertinghe, they were stopped by several regiments passing. They waited, waited, waited, till at last an officer, seeing their distress, gave a signal, and the soldiers halted to allow them to cross. Despairing of ever reaching Poperinghe with their load, they called at the house where Mother Prioress had been received that morning, and begged to leave the little carriage and its contents there. They then walked on more easily, and were able to get to Lady Abbess before nightfall.