CHAPTER X

A SECOND ATTEMPT TO REVISIT YPRES

Were we, then, to leave Belgium without seeing our beloved monastery again? The thought was too dreadful. This time Dame Placid begged to be allowed to venture back, and asked Dame Columban and Dame Patrick if they would go with her. They at once agreed; and having begged a blessing from Mother Prioress, started off, accompanied by the two servants of Madame Boone, poor Mother Prioress being still unwell and quite unable to accompany them, to her great disappointment. Dame Columban and Dame Patrick will again tell the story.

‘We were now determined to succeed—it was our last chance.

‘We had not gone far, when the whirr of an aeroplane was heard overhead. It flew too low to be an enemy, so we wished it good-speed, and passed on. Shortly after, some fugitives met us, who, seeing the direction we were taking, stared aghast, and told us that the Germans were bombarding Ypres worse than ever. Should we turn back? Oh no! it was our last chance. We continued bravely. Soon, others stopped us with the same story, but, turning a deaf ear to the horrors they related, we pushed on. Over an hour had passed, when, after a brisk walk, Vlamertinghe came in sight. More than half our journey was accomplished. Just as we approached the railway station (we had again taken the railway track) we heard the whirr of an aeroplane, then a volley of shots flew up towards the aeroplane. We knew what that meant. We could see the shots of the Allies bursting in the air, some near the Taube, some far away; alas! none hit it. What should we do? We determined to risk it; and passing under Taube, bombs, shots, and all, we hastened through the railway station—soldiers, men, women and children staring at “these strange Benedictine nuns!”

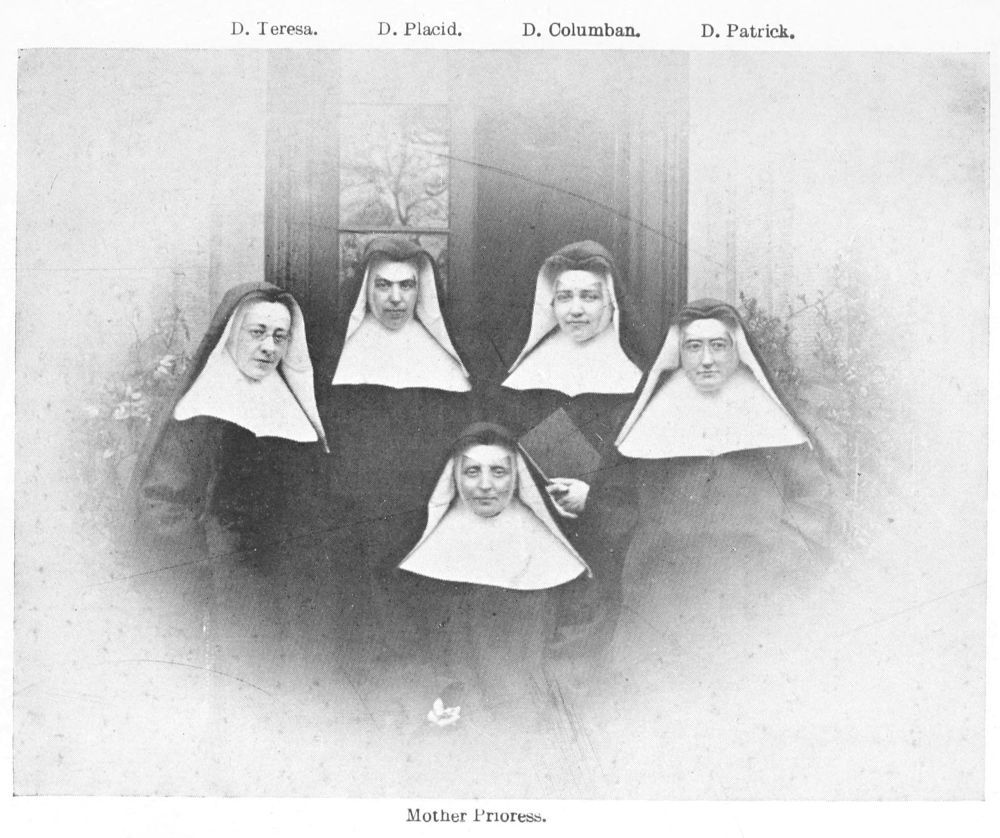

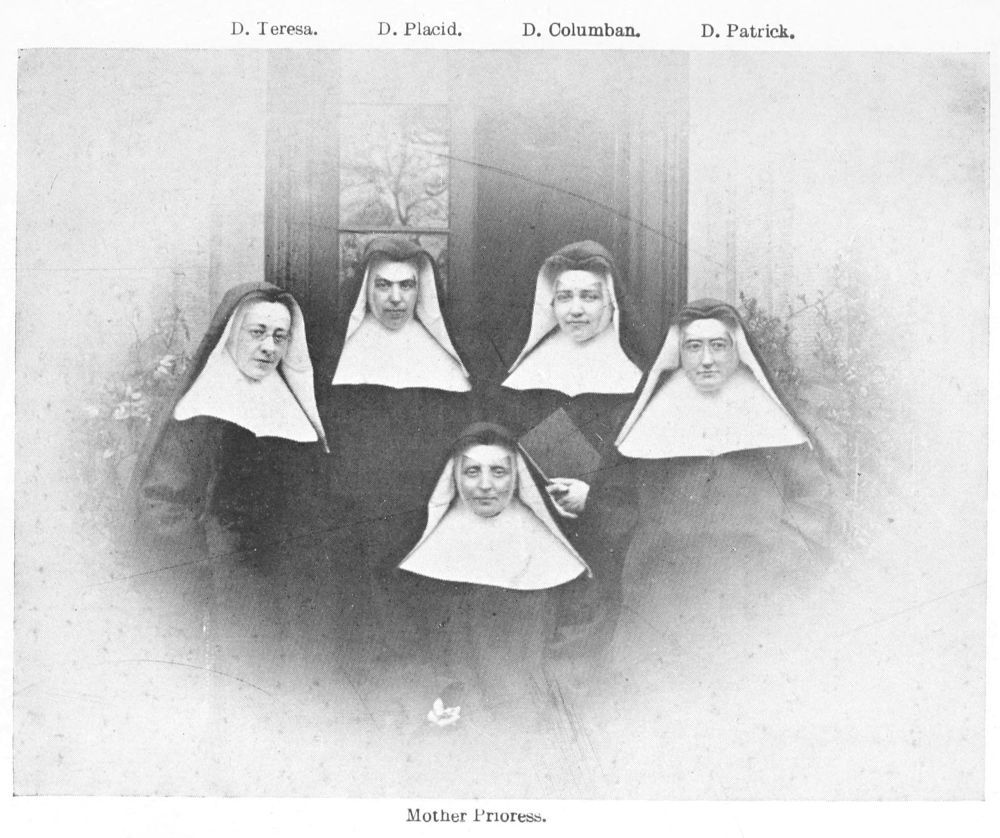

D. TERESA. D. PLACID. D. COLUMBAN. D. PATRICK.

MOTHER PRIORESS.

THE MOTHER PRIORESS, DAME TERESA, AND THE THREE NUNS WHO REVISITED YPRES.

‘Hurrying on, we met two priests coming from Ypres. We stopped to ask advice. They told us that our undertaking was decidedly dangerous. There was hardly a person left in the town; they had gone in in the morning to see if they could be of any use, and were now leaving, not daring to stop the night. They told us that there was still one priest who remained in the establishment of the mad people, just outside Ypres, and that we could always call on him, if we could not manage to reach our convent; but they added that he also was leaving the next day with all his poor protégés. We made up our minds to risk all; so, asking the priests’ blessing, we went our way. Other people tried in vain to make us turn back, especially two men who assured us we should never be able to accomplish our project. We thanked them for the interest they showed in our behalf, and asked them if they would be so kind as to call at the convent at Poperinghe and tell Mother Prioress not to be anxious if we did not return that night, and not to expect us till the next day. We were now approaching the cross-roads which had proved so fatal on Wednesday. A Belgian officer on a bicycle stopped to ask where we were going. We told him. He said it was simple madness to think of doing such a thing. He had been with his soldiers trying to mend the roads a little farther on, and had been obliged to leave off on account of the shells which were flying in all directions. We thanked him, but said we would risk it all the same. Arriving on the high road, we soon found ourselves in presence of a French policeman who asked where we were going. “To Ypres!” was the determined reply. “No one can pass. You must go back.” What were we to do? We determined to go on. Were there no means of getting in by another way? While we stood as though rooted to the ground, we caught sight of a French Chasseur on the other side of the road, who seemed to have some authority, and who was trying to console a woman and two weeping children. We immediately applied to him, and told him our distress. He answered kindly, but told us, all the same, that he was afraid we should not be able to enter Ypres. We begged to be allowed to continue, if only to try. He smiled and said: “If you really wish it, then pass on.” And on his writing down a passport, we went on triumphantly. It seemed as though God were helping us.

‘We had been so taken up with all that had passed that we had thought of nothing else, but now that we were in sight of the goal we realised that it was freezing hard. The stars were shining brightly, from time to time a light flashed in the distance, then a sinister whirr, followed by an explosion, which told us that the Germans were not going to let us pass as easily as did the French Chasseur. Wondering as to how we should succeed, we came across an English sentinel, and so asked his advice. He told us that he thought there was no chance whatever of our getting into the town. He said that he himself had been obliged to abandon his post on account of the shells, that the troops in the town had been ordered to leave, and that those coming in had been stopped. (We now remembered having seen a regiment of French soldiers setting out from Poperinghe at the same time as we had done, and then they were suddenly stopped, while we went on and saw them no more.) Despite what the sentinel told us, we remained unpersuaded. Seeing several soldiers going in and out of a house just opposite, we thought it would be as well to ask a temporary shelter till the bombardment should lessen. We ventured to ask admission, when what was our surprise to receive the warmest of welcomes and the kindest offers of hospitality. We could not have found a better spot. The family was thoroughly Christian; and, in this time of distress, the door of the house stood open day and night for all who were in need. How much more for nuns, and more especially enclosed nuns like ourselves! They had seen us passing on our way to Poperinghe, just a fortnight before, and had accompanied our wanderings with a prayer. A few days ago they had also given refreshment to the Poor Clares who had taken refuge at Vlamertinghe; and now their only desire was that God would spare their little house, that they might continue their deeds of mercy and true charity. To give us pleasure, they introduced an Irish gentleman who was stopping with them, since the Germans had chased him out of Courtrai. A lively conversation soon began, while the good woman of the house prepared us a cup of hot coffee and some bread and butter. After this, the Irish gentleman, whose name was Mr. Walker, went out to investigate, to see if it would not be possible for us to continue our walk. After about half an hour’s absence, during which we were entertained by our host (M. Vanderghote, 10 Chaussée de Poperinghe, Ypres), who made his five children and two nieces come in to say good-night to us before going to bed, Mr. Walker returned, saying it was a sheer impossibility to enter the town that evening, as the shells were falling at the rate of two every three minutes. He had called on M. l’Abbé Neuville, the priest above mentioned, Director of the Asylum, who said he would give us beds for the night, and then we could assist at his Mass at 6.30 next morning. The latter part of the proposition we gladly accepted; but as to the first, we were afraid of abusing his goodness, and preferred, if our first benefactor would consent, to remain where we were until morning. Our host was only too pleased, being sorry that he could not provide us with beds. He then forced us to accept a good plate of warm butter-milk; after which, provided with blankets and shawls, we made ourselves as comfortable as we could for the night. Needless to say, we did not sleep very well and were entertained, till early morning, with explosions of bombs and shells, and the replying fire of the Allies’ guns. Once a vigorous rattling of the door-handle aroused us, but we were soon reassured by hearing M. Vanderghote inviting the poor half-frozen soldier, who had thus disturbed us, to go to the kitchen to take something warm. Before 6, we began to move, and performed our ablutions as best we could. The eldest son of the family now came to fetch us, to show us the way to the church of the asylum, where we had the happiness of hearing Holy Mass and receiving Holy Communion. When Mass was over we wound our way once more through the dimly-lit cloisters of the asylum, while we could not help smiling at the apparent appropriateness of the place we had chosen with the foolhardy act we were undertaking—of risking our lives in thus entering a town which even our brave troops had been obliged to evacuate.

‘Once outside the asylum, we found Mr. Walker waiting for us, with the eldest daughter and three sons of M. Vanderghote, who were pushing a hand-cart. We set off at a brisk pace along the frozen road. Passing by a few French soldiers, who looked amazed at our apparition, we soon entered the doomed town. There, a truly heart-breaking sight awaited us. Broken-down houses, whose tottering walls showed remains of what had once been spacious rooms—buildings, half-demolished, half-erect,—met our wondering gaze everywhere. Windows, shattered in a thousand pieces, covered the ground where we walked; while, in the empty casements, imagination pictured the faces of hundreds of starving, homeless poor, whose emaciated features seemed to cry to heaven for vengeance on the heartless invaders of their peaceful native land.

‘But we durst not stop; the thought ever uppermost in our hearts was our own beloved Abbey. How should we find it? We pushed on as quickly as we could, but the loose stones, bricks, beams and glass made walking a difficult matter, and twice, having passed half-way down a street, we were obliged to retrace our steps, owing to the road being entirely blocked by overthrown buildings. Here and there, we saw some poor creature looking half-frightened, half-amazed at seeing us, while suddenly turning a corner we came to a pool of frozen water, where three street boys were amusing themselves sliding on the ice. Their mirth seemed almost blameful among so many trophies of human misery! We now came in sight of St. Peter’s Church, which at first glance appeared untouched; but coming round, past the calvary, we saw that the porch had been struck.

‘One moment more, and we were in La Rue St. Jacques—nay, in front of our dear old home. The pavements were covered with débris of all kinds, but the other buildings had largely contributed to the pile. We hardly dared to raise our eyes; yet the Monastery was there as before, seemingly untouched, save for the garrets over the nuns’ cells, where the shell had burst before we had left. We were now greeted by a familiar voice, and looking round found the poor girl, Hélène, who was anxiously enquiring if we were returning to the convent. But there was no time to waste. The Germans, who had stopped bombarding Ypres at about 3 A.M., might recommence at any moment, and then we should have to fly; so we went to the door of the Director’s house to try to get into the Abbey. What was our astonishment to find Oscar, our old servant-man, there. Probably he was still more astonished than we, for he had never dared to come to the convent since he had left, and would surely feel, at the least, uncomfortable at our unexpected arrival. However, it was certainly not the moment to think of all these things, so we went in. The whole building seemed but one ruin. In the drawing-room, where the priest’s breakfast things—laid a fortnight before—were still on the table, the ceiling was literally on the floor; the staircase was quite blocked with cement, mortar, wall-paper, and bricks; the sacristy, where we were assembled when the first shell fell, was untouched. The church, except for some five or six holes in the roof, was as we left it; but the altar, stripped of all that had once made it so dear to us, spoke volumes to our aching hearts. Mounting the seven steps which led into the choir, we found ourselves once more in that beloved spot. The windows on the street side were in atoms; otherwise, all was intact. Our dearest Lord had watched over His House, His Royal State Chamber, where He was always ready to hold audience with His Beloved Spouses. We tore ourselves away, and flew to secure our breviaries, great-habits, and other things which the other nuns had recommended to us. Everywhere we went, dust and dirt covered the rooms, while a great many windows were broken. The statues of Our Blessed Lady and St. Joseph were unharmed, as also those of Our Holy Father St. Benedict and our Holy Mother St. Scholastica. Little Jesus of Prague had His crown at His feet, instead of on His head; one crucifix was broken in two! The cells were almost quite destroyed, big holes in the ceilings, the windows broken, the plaster down, frozen pools of water on the floor. We hastened to the garrets, where things were still worse. The roof in this part was completely carried away, leaving full entrance to hail, snow, and rain; strong rafters and beams, which seemed made to last unshaken till the end of the world, were rent asunder or thrown on the floor; the huge iron weights of the big clock had rolled to the other end of the garrets; the scene of destruction seemed complete. We turned away; the other part looked secure, the apples and pears lying rotting away on the floors, where we had put them to ripen. In the noviceship, the ceiling was greatly damaged; whilst down in the cloisters, by the grotto of our Lady of Lourdes, a bomb had perforated the roof, the grotto remaining untouched. These seemed to be the principal effects of the invaders’ cruelty, as far as our Abbey was concerned.

‘We now came across our old carpenter, who had also come into the house with Oscar, and who had already put up planks on the broken windows in the choir, promising to do all he could to preserve the building. He also told us that one of the biggest German bombs had fallen in the garden, but had not exploded, so the French police had been able to take it away—another mark of God’s loving care over us; for, had the bomb burst, it would have utterly destroyed our Monastery. We were now obliged to leave. When should we see the dear old spot again? and in what state would it be if we ever did return?’