CHAPTER II.

THE MONK HILDEBRAND.

It is a melancholy thing looking back through the long depths of history to find how slow the progress is, even if it can be traced at all, from one age to another, and how, though the dangers and the evils to which they are liable change in their character from time to time, their gravity, their hurtfulness, and their rebellion against all that is best in morals, and most advantageous to humanity, scarcely diminish, however completely altered the conditions may be. We might almost doubt whether the vast and as yet undetermined possibilities of the struggle which has begun in our days between what is called Capital and Labour, the theories held against all experience and reason of a rising Socialism, and the mad folly of Anarchism, which is their immediate climax—are not quite as dangerous to the peace of nations as were the tumults of an age when every man acted by the infallible rule that

He should take who had the power

And he should keep who can—

the principle being entirely the same, though the methods may be different. This strange duration of trouble, equal in intensity though different in form, is specially manifest in a history such as that which we take up from one age to another in so remarkable a development of life and government as Mediæval Rome. We leave the city relieved of some woes, soothed from some troubles, fed by much charity, and weeping apparently honest tears over Gregory the first of the name—although that great man was scarcely dead before the crowd was taught to believe that he had impoverished the city by feeding them, and were scarcely prevented from burning his library as a wise and fit revenge. Still it might have been expected that Rome and her people would have advanced a step upon the pedestal of such a life as that of Gregory: and in fact he left many evils redressed, the commonwealth safer, and the Church more pure.

But when we turn the page and come, four hundred years later, to the life of another Gregory, upon what a tumultuous world do we open our eyes: what blood, what fire, what shouts and shrieks of conflict: what cruelty and shame have reigned between, and still remained, ever stronger than any influence of good men, or amelioration of knowledge! Heathenism, save that which is engrained in the heart of man, had passed away. There were no more struggles with the relics of the classical past: the barbarians who came down in their hordes to overturn civilisation had changed into settled nations, with all the paraphernalia of state and great imperial authority—shifting indeed from one race to another, but always upholding a central standard. All the known world was nominally Christian. It was full of monks dedicated to the service of God, of priests, the administrants of the sacraments, and of bishops as important as any secular nobles—yet what a scene is that upon which we look out through endless smoke of battle and clashing of swords! Rome, at whose gates Alaric and Attila once thundered, was almost less secure now, and less easily visited than when Huns and Goths overran the surrounding country. It was encircled by castles of robber nobles, who infested every road, sometimes seizing the pilgrims bound for Rome, with their offerings great and small, sometimes getting possession of these offerings in a more thorough way by the election of a subject Pope taken from one of their families, and always ready on every occasion to thrust their swords into the balance and crush everything like freedom or purity either in the Church or in the city. In the early part of the eleventh century there were two if not three Popes in Rome. "Benedict IX. officiated in the church of St. John Lateran, Sylvester III. in St. Peter's, and John XX. in the church of St. Mary," says Villemain in his life of Hildebrand: the name of the last does not appear in the lists of Platina, but the fact of this profane rivalry is beyond doubt.

The conflict was brought to an end for the moment by a very curious transaction. A certain dignified ecclesiastic, Gratiano by name, the Cardinal-archdeacon of St. John Lateran, who happened to be rich, horrified by this struggle, and not sufficiently enlightened as to the folly and sin of doing evil that good might come—always, as all the chronicles seem to allow, with the best motives—bought out the two competitors, and procured his own election under the title of Gregory VI. But this mistaken though well-meant act had but brief success. For, on the arrival in 1046 of the Emperor Henry III. in Italy, at a council called together by his desire, Gregory was convicted of the strange bargain he had made, or according to Baronius of the violent means taken to enforce it, and was deposed accordingly, along with his two predecessors. It was this Pope, in his exile and deprivation, who first brought in sight of a universe which he was born to rule, a young monk of Cluny, Hildebrand—German by name, but Italian in heart and race—who had already moved much about the world with the extraordinary freedom and general access everywhere which we find common to monks however humble their origin. From his monastic home in Rome he had crossed the Alps more than once; he had been received and made himself known at the imperial court, and was on terms of kindness with many great personages, though himself but a humble brother of his convent. No youthful cleric in our modern world nowadays would find such access everywhere, though it is still possible that a young Jesuit for instance, noted by his superiors for ability or genius, might be handed on from one authority to another till he reached the highest circle. But it is surprising to see how free in their movements, how adventurous in their lives, the young members of a brotherhood bound under the most austere rule then found it possible to be.

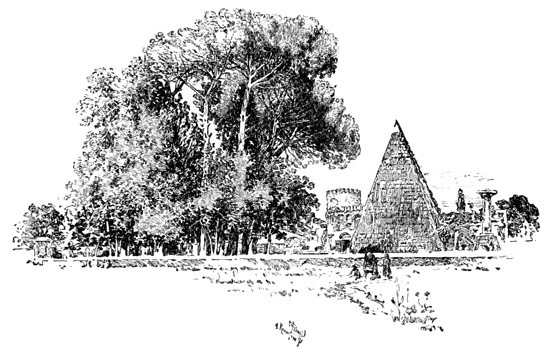

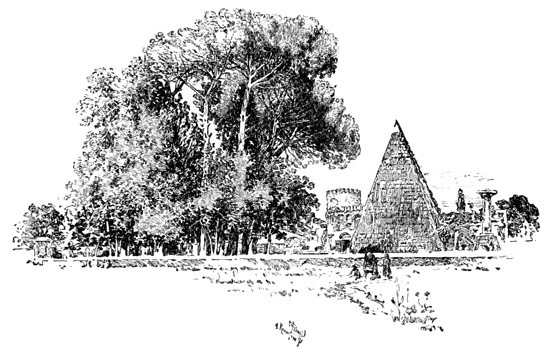

Hildebrand was, like so many other great Churchmen, a child of the people. He was the son of a carpenter in a Tuscan village, who, however, possessed one of those ties with the greater world which a clergy drawn from the people affords to the humblest, a brother or other near relation who was the superior of a monastery in Rome. There the little Tuscan peasant took his way in very early years to study letters, having already given proof of great intelligence such as impressed the village and called forth prophecies of the highest advancement to come. His early education brings us back to the holy mount of the Aventine, on which we have already seen so many interesting assemblies. The monastery of St. Mary has endured as little as the house of Marcella, though it is supposed that in the church of S. Maria Aventina there may still remain some portion of the original buildings. But the beautiful garden of the Priorato, so great a favourite with the lovers of the picturesque, guards for us, in that fidelity of nature which time cannot discompose, the very spot where that keen-eyed boy must have played, if he ever played, or at least must have dreamed the dreams of an ambitious young visionary, and perhaps, as he looked out musing to where the tombs of the Apostles gleamed afar on the other side of Tiber, have received the inheritance of that long hope and vision which had been slowly growing in the minds of Popes and priests—the hope of making the Church the mistress and arbiter of the nations, the supreme and active judge among all tumults of earthly politics and changes of power. He was nourished from his childhood in the house of St. Peter, says the biographer of the Acta Sanctorum. It would be more easy to realise the Apostle's sway, and that of his successors, on that mount of vision, where day and night, by sun and moon, the great temple of Christendom, the centre of spiritual life, shone before his eyes, than on any other spot. That wonderful visionary sovereignty, the great imagination of a central power raised above all the disturbances of worldly life, and judging austerely for right and against wrong all the world over—unbiassed, unaffected by meaner motives, the great tribunal from which justice and mercy should go forth over the whole earth—could there be a more splendid ideal to till the brain of an ardent boy? It is seldom that such an ideal is recognised, or such dreams as these believed in. We know how little the Papacy has carried it out, and how the faults and weaknesses even of great men have for many centuries taken all possibility from it. But it was while that wonderful institution was still fully possible, the devoutest of imaginations, a dream such as had never been surpassed in splendour and glory, that young Hildebrand looked out to Peter's prison on the Janiculum opposite, and from thence to Peter's tomb, and dreamt of Peter's white throne of justice dominating the darkness and the self-seeking of an uneasy world.

The monastery of St. Mary, a Benedictine house, must have been noted in its time. Among the teachers who instructed its neophytes was that same Giovanni Gratiano of whom we have just spoken, the arch-priest who devoted his wealth to the not ignoble purpose of getting rid of two false and immoral Popes: though perhaps his motives would have been less misconstrued had he not been elected in their place. And there was also much fine company at the monastery in those days—bishops with their suites travelling from south and north, seeking the culture and piety of Rome after long banishment from intellectual life—and at least one great abbot, more important than a bishop, Odilon of Cluny, at the head of one of the greatest of monastic communities. All of these great men would notice, no doubt, the young nephew of the superior, the favourite of the cloister, upon whom many hopes were already beginning to be founded, and in whose education every one loved to have a hand. One of these bishops was said afterwards to have taught him magical arts, which proves at least that they took a share in the training of the child of the convent. At what age it was that he was transferred to Cluny it is impossible to tell. Dates do not exist in Hildebrand's history until he becomes visible in the greater traffic of the world. He was born between 1015 and 1020—this is the nearest that we can approach to accuracy. He appears in full light of history at the deposition of Gratiano (Gregory VI.) in 1045. In the meantime he passed through a great many developments. Probably the youth—eager to see the world, eager too to fulfil his vocation, to enter upon the mortifications and self-abasement of a monk's career, and to "subdue the flesh" in true monkish fashion, as well as by the fatigues of travel and the acquirement of learning—followed Odilon and his train across i monti, a favourite and familiar, when the abbot returned from Rome to Cluny. It could not be permitted in the monkish chronicles, even to a character like that of the austere Hildebrand all brain and spirit, that he had no flesh to subdue. And we are not informed whether it was at his early home on the Aventine or in the great French monastery that he took the vows. The rule of Cluny was specially severe. One poor half hour a day was all that was permitted to the brothers for rest and conversation. But this would not matter much, we should imagine, to young Hildebrand, all on fire for work, and full of a thousand thoughts.

How a youth of his age got to court, and was heard and praised by the great Emperor Henry III., the head of Christendom, is not known. Perhaps he went in attendance on his abbot, perhaps as the humble clerk of some elder brethren bearing a complaint or an appeal; the legend goes that he became the tutor and playfellow of the little prince, Henry's son, until the Emperor had a dream in which he saw the stranger, with two horns on his head, with one of which he pushed his playfellow into the mud—significant and alarming vision which was a reasonable cause for the immediate banishment of Hildebrand. The dates, however, if nothing else, make this story impossible, for the fourth Henry was not born within the period named. At all events the young monk was sufficiently distinguished to be brought under the Emperor's notice and to preach before him, though we are not informed elsewhere that Hildebrand had any reputation as a preacher. He was no doubt full of earnestness and strong conviction, and that heat of youth which is often so attractive to the minds of sober men. Henry declared that he had heard no man who preached the word of God with so much faith: and the imperial opinion must have added much to his importance among his contemporaries. On the other hand, the great world of Germany and its conditions must have given the young man many and strange revelations. Nowhere were the prelates so great and powerful, nowhere was there so little distinction between the Church and the world. Many of the clergy were married, and left, sometimes their cures, often a fortune amassed by fees for spiritual offices, to their sons: and benefices were bought and sold like houses and lands, with as little disguise. A youth brought up in Rome would not be easily astonished by the lawlessness of the nobles and subject princes of the empire, but the importance of a central authority strong enough to restrain and influence so vast a sphere, and so many conflicting powers, must have impressed upon him still more forcibly the supreme ideal of a spiritual rule more powerful still, which should control the nations as a great Emperor controlled the electors who were all but kings. And we know that it was now that he was first moved to that great indignation, which never died in his mind, against simony and clerical license, which were universally tolerated, if not acknowledged as the ordinary rule of the age. It was high time that some reformer should arise.

It was not, however, till the year 1046, on the occasion of the deposition of Gregory VI. for simony, that Hildebrand first came into the full light of day. Curiously enough, the first introduction of this great reformer of the Church, the sworn enemy of everything simoniacal, was in the suite of this Pope deposed for that sin. But in all probability the simony of Gregory VI. was an innocent error, and resulted rather from a want of perception than evil intention, of which evidently there was none in his mind. He made up to the rivals who held Rome in fee, for the dues and tributes and offerings which were all they cared for, by the sacrifice of his own fortune. If he had not profited by it himself, if some one else had been elected Pope, no stain would have been left upon his name: and he seems to have laid down his dignities without a murmur: but his heart was broken by the shame and bitter conviction that what he had meant for good was in reality the very evil he most condemned. Henry proceeded on his march to Rome after deposing the Pope, apparently taking Gregory with him: and there without any protest from the silenced and terrified people, nominated a German bishop of his own to the papal dignity, from whose hands he himself afterwards received the imperial crown. He then returned to Germany, sweeping along with him the deposed and the newly-elected Popes, the former attended in silence and sorrow by Hildebrand, who never lost faith in him, and to the end of his life spoke of him as his master.

A stranger journey could scarcely have been. The triumphant German priests and prelates surrounding the new head of the Church, and the handful of crestfallen Italians following the fallen fortunes of the other, must have made a strange and not very peaceful conjunction. "Hildebrand desired to show reverence to his lord," says one of the chronicles. Thus his career began in the deepest mortification and humiliation, the forced subjection of the Church which it was his highest aim and hope to see triumphant, to the absolute force of the empire and the powers of this world.

Pope Gregory reached his place of exile on the banks of the Rhine, with his melancholy train, in deep humility; but that exile was not destined to be long. He died there within a few months: and his successor soon followed him to the grave. For a short and disastrous period Rome seems to have been left out of the calculations altogether, and the Emperor named another German bishop, whom he sent to Rome under charge of the Marquis, or Margrave, or Duke of Tuscany—for he is called by all these titles. This Pope, however, was still more short-lived, and died in three weeks after his proclamation, by poison it was supposed. It is not to be wondered at if the bishops of Germany began to be frightened of this magnificent nomination. Whether it was the judgment of God which was most to be feared, or the poison of the subtle and scheming Romans, the prospect was not encouraging. The third choice of Henry fell upon Bruno, the bishop of Toul, a relative of his own, and a saintly person of commanding presence and noble manners. Bruno, as was natural, shrank from the office, but after days of prayer and fasting yielded, and was presented to the ambassadors from Rome as their new Pope. Thus the head of the Church was for the third time appointed by the Emperor, and the ancient privilege of his election by the Roman clergy and people swept away.

But Henry was not now to meet with complete submission and compliance, as he had done before. The young Hildebrand had shown no rebellious feeling when his master was set aside: he must have, like Gregory, felt the decision to be just. And after faithful service till the death of the exile, he had retired to Cluny, to his convent, pondering many things. We are not told what it was that brought him back to Germany at this crisis of affairs, whether he were sent to watch the proceedings, or upon some humbler mission, or by the mere restlessness of an able young man thirsting to be employed, and the instinct of knowing when and where he was wanted. He reappeared, however, suddenly at the imperial court during these proceedings; and no doubt watched the summary appointment of the new Pope with indignation, injured in his patriotism and in his churchmanship alike, by an election in which Rome had no hand, though otherwise not dissatisfied with the Teutonic bishop, who was renowned both for piety and learning. The chronicler pauses to describe Hildebrand in this his sudden reintroduction to the great world. "He was a youth of noble disposition, clear mind, and a holy monk," we are told. It was while Bishop Bruno was still full of perplexities and doubts that this unexpected counsellor appeared, a man, though young, already well known, who had been trained in Rome, and was an authority upon the customs and precedents of the Holy See. He had been one of the closest attendants upon a Pope, and knew everything about that high office—there could be no better adviser. The anxious bishop sent for the young monk, and Hildebrand so impressed him with his clear mind and high conception of the papal duties, that Bruno begged him to accompany him to Rome.

He answered boldly, "I cannot go with you." "Why?" said the Teuton prelate with amazement. "Because without canonical institution," said the daring monk, "by the sole power of the emperor, you are about to seize the Church of Rome."

Bruno was greatly startled by this bold speech. It is possible that he, in his distant provincial bishopric, had no very clear knowledge of the canonical modes of appointing a Pope. There were many conferences between the monk and the Pope-elect, the young man who was not born to hesitate but saw clear before him what to do, and his elder and superior, who was neither so well informed nor so gifted. Bruno, however, if less able and resolute, must have been a man of a generous and candid mind, anxious to do his duty, and ready to accept instruction as to the best method of doing so, which was at the same time the noblest way of getting over his difficulties. He appeared before the great diet or council assembled in Worms, and announced his acceptance of the pontificate, but only if he were elected to it according to their ancient privileges by the clergy and people of Rome. It does not appear whether there was any resistance to this condition, but it cannot have been of a serious character, for shortly after, having taken farewell of his own episcopate and chapter, he set out for Rome.

This is the account of the incident given by Hildebrand himself when he was the great Pope Gregory, towards the end of his career. It was his habit to tell his attendants the story of his life in all its varied scenes, during the troubled leisure of its end, as old men so often love to do. "Part I myself heard, and part of it was reported to me by many others," says one of the chroniclers. There is another account which has no such absolute authority, but is not unreasonable or unlikely, of the same episode, in which we are told that Bishop Bruno on his way to Rome turned aside to visit Cluny, of which Hildebrand was prior, and that the monk boldly assailed the Pope, upbraiding him with having accepted from the hand of a layman so great an office, and thus violently intruded into the government of the Church. In any case Hildebrand was the chief actor and inspirer of a course of conduct on the part of Bruno which was at once pious and politic. The papal robes which he had assumed at Worms on his first appointment were taken off, the humble dress of a pilgrim assumed, and with a reduced retinue and in modest guise the Pope-elect took his way to Rome. His episcopal council acquiesced in this change of demeanour, says another chronicler, which shows how general an impression Hildebrand's eloquence and the fervour of his convictions must have made. It was a slow journey across the mountains lasting nearly two months, with many lingerings on the way at hospitable monasteries, and towns where the Emperor's cousin could not but be a welcome guest. Hildebrand, who must have felt the great responsibility of the act which he had counselled, sent letter after letter, whenever they paused on their way, to Rome, describing, no doubt with all the skill at his command, how different was this German bishop from the others, how scrupulous he was that his election should be made freely if at all, in what humility he, a personage of so high a rank, and so many endowments, was approaching Rome, and how important it was that a proper reception should be given to a candidate so good, so learned, and so fit in every way for the papal throne. Meanwhile Bishop Bruno, anxious chiefly to conduct himself worthily, and to prepare for his great charge, beguiled the way with prayers and pious meditations, not without a certain timidity as it would appear about his reception. But this timidity turned out to be quite uncalled for. His humble aspect, joined to his high prestige as the kinsman of the emperor, and the anxious letters of Hildebrand had prepared everything for Bruno's reception. The population came out on all sides to greet his passage. Some of the Germans were perhaps a little indignant with this unnecessary humility, but the keen Benedictine pervaded and directed everything while the new Pope, as was befitting on the eve of assuming so great a responsibility, was absorbed in holy thought and prayer. The party had to wait on the further bank of the Tiber, which was in flood, for some days, a moment of anxious suspense in which the pilgrims watched the walls and towers of the great city in which lay their fate with impatience and not without alarm. But as soon as the water fell, which it did with miraculous rapidity, the whole town, with the clergy at its head, came out to meet the new-comers, and Leo IX., one of the finest names in the papal lists, entering barefooted and in all humility by the great doors of St. Peter's, was at once elected unanimously, and received the genuine homage of all Rome. One can imagine with what high satisfaction, yet with eyes ever turned to the future, content with no present achievement, Hildebrand must have watched the complete success of his plan.

This event took place, Villemain tells us (the early chroniclers, as has been said, are most sparing of dates), in 1046, a year full of events. Muratori in his annals gives it as two years later. Hildebrand could not yet have attained his thirtieth year in either case. He was so high in favour with the new Pope, to whom he had been so wise a guide, that he was appointed at once to the office of Economico, a sort of Chancellor of the Exchequer to the Court of Rome, and at the same time was created Cardinal-archdeacon, and abbot of St. Paul's, the great monastery outside the walls. Platina tells us that he received this charge as if the Pope had "divided with him the care of the keys, the one ruling the church of St. Peter and the other that of St. Paul."

That great church, though but a modern building now, after the fire which destroyed it seventy years ago, and standing on the edge of the desolate Campagna, is still a shrine universally visited. The Campagna was not desolate in Hildebrand's days, and the church was of the highest distinction, not only as built upon the spot of St. Paul's martyrdom, but for its own splendour and beauty. It is imposing still, though so modern, and with so few relics of the past. But the pilgrim of to-day, who may perhaps recollect that over its threshold Marcella dragged herself, already half dead, into that peace of God which the sanctuary afforded amid the sack and the tortures of Rome, may add another association if he is so minded in the thought of the great ecclesiastic who ruled here for many years, arriving, full of zeal and eager desire for universal reform, into the midst of an idle crew of depraved monks, who had allowed their noble church to fall into the state of a stable, while they themselves—a mysterious and awful description, yet not perhaps so alarming to us as to them—"were served in the refectory by women," the first and perhaps the only, instance of female servants in a monastery. Hildebrand made short work of these ministrants. He had a dream—which no doubt would have much effect on the monks, always overawed by spiritual intervention, however material they might be in mind or habits—in which St. Paul appeared to him, working hard to clear out and purify his desecrated church. The young abbot immediately set about the work indicated by the Apostle, "eliminating all uncleanness," says his chronicler: "and supplying a sufficient amount of temperate food, he gathered round him a multitude of honest monks faithful to their rule."

Hildebrand's great business powers, as we should say, enabled him very soon to put the affairs of the convent in order. The position of the monastery outside the city gates and defences, and its thoroughly disordered condition, had left it open to all the raids and attacks of neighbouring nobles, who had found the corrupt and undisciplined monks an easy prey; but they soon discovered that they had in the new abbot a very different antagonist. In these occupations Hildebrand passed several years, establishing his monastery on the strongest foundations of discipline, purity, and faith. Reform was what the Church demanded in almost every detail of its work. Amid the agitation and constant disturbance outside, it had not been possible to keep order within, nor was an abbot who had bought his post likely to attempt it: and a great proportion of the abbots, bishops, and great functionaries of the Church had bought their posts. In the previous generation it had been the rule. It had become natural, and disturbed apparently no man's conscience. A conviction, however, had evidently arisen in the Church, working by what influences we know not, but springing into flame by the action of Hildebrand, and by his Pope Leo, that this state of affairs was monstrous and must come to an end. The same awakening has taken place again and again in the Church as the necessity has unfortunately arisen: and never had it been more necessary than now. Every kind of immorality had been concealed under the austere folds of the monk's robe; the parish priests, especially in Germany, lived with their wives in a calm contempt of all the Church's laws in that respect. This, which to us seems the least of their offences, was not so in the eyes of the new race of Church reformers. They thought it worse than ordinary immoral relations, as counterfeiting and claiming the title of a lawful union; and to the remedy of this great declension from the rule of the Church, and of the still greater scandal of simony, the new Pope's utmost energies were now directed.

PYRAMID OF CAIUS CESTIUS.

A very remarkable raid of reformation, which really seems the most appropriate term which could be used, took place accordingly in the first year of Leo IX.'s reign. We do not find Hildebrand mentioned as accompanying him in his travels—probably he was already too deeply occupied with the cleansing out of St. Paul's physically and morally, to leave Rome, of which, besides, he had the care, in all its external as well as spiritual interests, during the Pope's absence: but no doubt he was the chief inspiration of the scheme, and had helped to organise all its details. Something even of the subtle snare in which his own patron Gregory had been caught was in the plan with which Hildebrand, thus gleaning wisdom from suffering, sent forth his Pope. After holding various smaller councils in Italy, Leo crossed the mountains to France, where against the wish of the Emperor, he held a great assembly at Rheims. The nominal occasion of the visit was the consecration of that church of St. Remy, then newly built, which is still one of the glories of a city so rich in architectural wealth. The body of St. Remy was carried, with many wonderful processions, from the monastery where it lay, going round and round the walls of the mediæval town and through its streets with chants and psalms, with banner and cross, until at last it was deposited solemnly on an altar in the new building, now so old and venerable. Half of France had poured into Rheims for this great festival, and followed the steps of the Pope and hampered his progress—for he was again and again unable to proceed from the great throngs that blocked every street. This, however, though a splendid ceremony, and one which evidently made much impression on the multitude, was but the preliminary chapter. After the consecration came a wholly unexpected visitation, the council of Rheims, which was not concerned like most other councils with questions of doctrine, but of justice and discipline. The throne for the Pope was erected in the middle of the nave of the cathedral—not, it need scarcely be said, the late but splendid cathedral now existing—and surrounded in a circle by the seats of the bishops and archbishops. When all were assembled the object of the council was stated—the abolition of simony, and of the usurpation of the priesthood and the altar by laymen, and the various immoral practices which had crept into the shadow of the Church and been tolerated or authorised there. The Pope in his opening address adjured his assembled counsellors to help him to root out those tares which choked the divine grain, and implored them, if any among them had been guilty of the sin of simony, either by sale or purchase of benefices, that he should make a public confession of his sin.

Terrible moment for the bishops and other prelates, immersed in all the affairs of their times and no better than other men! The reader after all these centuries can scarcely fail to feel the thrill of alarm, or shame, or abject terror that must have run through that awful sitting as men looked into each other's faces and grew pale. The archbishop of Trèves got up first and declared his hands to be clean, so did t