CHAPTER II.

THE DELIVERER.

It was in this age of disorder and anarchy that a child was born, of the humblest parentage, on the bank of the Tiber, in an out-of-the-way suburb, who was destined to become the hero of one of the strangest episodes of modern history. His father kept a little tavern to which the Roman burghers, pushing their walk a little beyond the walls, would naturally resort; his mother, a laundress and water-carrier—one of those women who, with the port of a classical princess, balance on their heads in perfect poise and certainty the great copper vases which are still used for that purpose. It was the gossip of the time that Maddalena, the wife of Lorenzo, had not been without adventures in her youth. No less a person than Henry VII. had found shelter, it was said, in her little public-house when her husband was absent. He was in the dress of a pilgrim, but no doubt bore the mien of a gallant gentleman and dazzled the eyes of the young landlady, who had no one to protect her. When her son was a man it pleased him to suppose that from this meeting resulted the strange mixture of democratic enthusiasm and love of pomp and power which was in his own nature. It was not much to be proud of, and yet he was proud of it. For all the world he was the son of the poor innkeeper, but within himself he felt the blood of an Emperor in his veins. Maddalena died young, and when her son began to weave the visions which helped to shape his life, was no longer there to clear her own reputation or to confirm him in his dream.

These poor people had not so much as a surname to distinguish them. The boy Niccola was Cola di Rienzo, Nicolas the son of Laurence, as he is called in the Latin chronicles, according to that simplest of all rules of nomenclature which has originated so many modern names. "He was from his youth nourished on the milk of eloquence; a good grammarian, a better rhetorician, a fine writer," says his biographer. "Heavens, what a rapid reader he was! He made great use of Livy, Seneca, Tully, and Valerius Maximus, and delighted much to tell forth the magnificence of Julius Cæsar. All day long he studied the sculptured marbles that lie around Rome. There was no one like him for reading the ancient inscriptions. All the ancient writings he put in choice Italian; the marbles he interpreted. How often did he cry out, 'Where are these good Romans? where is their high justice? might I but have been born in their time?' He was a handsome man, and he adopted the profession of a notary."

We are not told how or where Cola attained this knowledge. His father was a vassal of the Colonna, and it is possible that some of the barons coming and going may have been struck by the brilliant, eager countenance of the innkeeper's son, and helped him to the not extravagant amount of learning thus recorded. His own character, and the energy and ambition so strangely mingled with imagination and the visionary temperament of a poet, would seem to have at once separated him from the humble world in which he was born. It is said by some that his youth was spent out of Rome, and that he only returned when about twenty, at the death of his father—a legend which would lend some show of evidence to the suggestion of his doubtful birth: but his biographer says nothing of this. It is also said that it was the death of his brother, killed in some scuffle between the ever-contending parties of Colonna and Orsini, which gave his mind the first impulse towards the revolution which he accomplished in so remarkable a way. "He pondered long," says his biographer, "of revenging the blood of his brother; and long he pondered over the ill-governed city of Rome, and how to set it right." But there is no definite record of his early life until it suddenly flashes into light in the public service of the city, and on an occasion of the greatest importance as well for himself as for Rome.

This first public employment which discloses him at once to us was a mission from the thirteen Buoni homini, sometimes called Caporoni, the heads of the different districts of the city, to Pope Clement VI. at Avignon, on the occasion of one of those temporary overturns of government which occurred from time to time, always of the briefest duration, but carrying on the traditions of the power of the people from age to age. He was apparently what we should call the spokesman of the deputation sent to explain the matter to the Pope, and to secure, if possible, some attention on the part of the Curia to the condition of the abandoned city.

"His eloquence was so great that Pope Clement was much attracted towards him: the Pope much admired the fine style of Cola, and desired to see him every day. Upon which Cola spoke very freely and said that the Barons of Rome were highway robbers, that they were consenting to murder, robbery, adultery, and every evil. He said that the city lay desolate, and the Pope began to entertain a very bad opinion of the Barons."

"But," adds the chronicler, "by means of Messer Giovanni of the Colonna, Cardinal, great misfortunes happened to him, and he was reduced to such poverty and sickness that he might as well have been sent to the hospital. He lay like a snake in the sun. But he who had cast him down, the very same person raised him up again. Messer Giovanni brought him again before the Pope and had him restored to favour. And having thus been restored to grace he was made notary of the Cammora in Rome, so that he returned with great joy to the city."

This succinct narrative will perhaps be a little more clear if slightly expanded: the chief object of the Roman envoy was to disclose the crimes of the "barons," whose true character Cola thus described to the Pope, on the part of the leaders of a sudden revolt, a sort of prophetical anticipation of his own, which had seized the power out of the hands of the two Senators and conferred it upon thirteen Buoni homini, heads of the people, who took the charge in the name of the Pope and professed, as was usual in its absence, an almost extravagant devotion to the Papal authority. The embassy was specially charged with the prayers and entreaties of the people that the Pope would return and resume the government of the city: and also that he would proclaim another jubilee—the great festival, accompanied by every kind of indulgence and pious promise to the pilgrims, attracted by it from all the ends of the earth to Rome—which had been first instituted by Pope Boniface VIII. in 1300 with the intention of being repeated once every century only. But a century is a long time; and the jubilee was most profitable, bringing much money and many gifts both to the State and the Church. The citizens were therefore very anxious to secure its repetition in 1350, and its future celebration every fifty years. The Pope graciously accorded the jubilee to the prayers of the Romans, and accepted their homage and desire for his return, promising vaguely that he would do so in the jubilee year if not before. So that whatever afterwards happened to the secretary or spokesman, the object of the mission was attained.

Elated by this fulfilment of their wishes, and evidently at the moment of his highest favour with the Pope, Cola sent a letter announcing this success to the authorities in Rome, which is the first word we hear from his own mouth. It is dated from Avignon, in the year 1343. He was then about thirty, in the full ardour of young manhood, full of visionary hopes and schemes for the restoration of the glories of Rome. The style of the letter, which was so much admired in those days, is too florid and ornate for the taste of a severer period, notwithstanding that his composition received the applause of Petrarch, and was much admired by all his contemporaries. He begins by describing himself as the "consul of orphans, widows and the poor, and the humble messenger of the people."

"Let your mountains tremble with happiness, let your hills clothe themselves with joy, and peace and gladness fill the valleys. Let the city arise from her long course of misfortunes, let her re-ascend the throne of her ancient magnificence, let her throw aside the weeds of widowhood and clothe herself with the garments of a bride. For the heavens have been opened to us and from the glory of the Heavenly Father has issued the light of Jesus Christ, from which shines forth that of the Holy Spirit. Now that the Lord has done this miracle, brethren beloved, see that you clear out of your city the thorns and the roots of vice, to receive with the perfume of new virtue the Bridegroom who is coming. We exhort you with burning tears, with tears of joy, to put aside the sword, to extinguish the flames of battle, to receive these divine gifts with a heart full of purity and gratitude, to glorify with songs and thanksgiving the name of our Lord Jesus Christ, and also to give humble thanks to His Vicar, and to raise to that supreme Pontiff, in the Capitol or in the amphitheatre, a statue adorned with purple and gold that the joyous and glorious recollection may endure for ever. Who indeed has adorned his country with such glory among the Ciceros, the Cæsars, Metullus, or Fabius, who are celebrated as liberators in our old annals and whose statues we adorn with precious stones because of their virtues? These men have obtained passing triumphs by war, by the calamities of the world, by the shedding of blood: but he, by our prayers and for the life, the salvation and the joy of all, has won in our eyes and in those of posterity an immortal triumph."

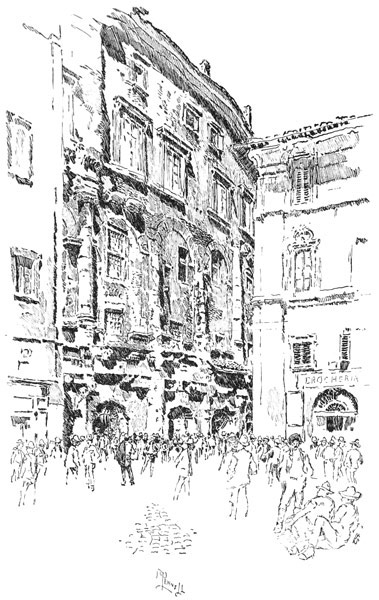

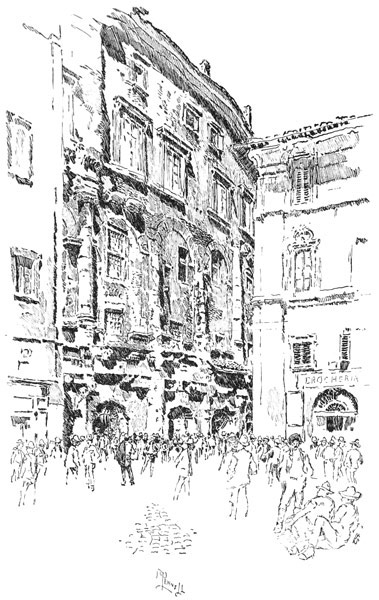

THEATRE OF MARCELLUS.

To face page 406.

It is like enough that these extravagant phrases expressed an exultation which was sufficiently genuine and sincere, for while he was absent the city of Rome desired and longed for its Pope, although when present it might do everything in its power to shake off his yoke. And Cola the ambassador, in whose mind as yet his own great scheme had not taken shape, might well believe that the gracious Pope who flattered him by such attention, who admitted him so freely to his august presence, and to whom he was as one who playeth very sweetly upon an instrument, was the man of all men to bring back again from anarchy and tumult the imperial city. He had even given up, it would seem, his enthusiasm for the classic heroes in this moment of hope from a more living and present source of help.

This elation however did not last. The Cardinal Giovanni Colonna, son of old Stefano, the head of that great house, of whose magnificent old age Petrarch speaks with so much enthusiasm, himself a man of many accomplishments, a scholar and patron of the arts—and to crown all, as has been said, the dear friend and patron of the poet—was one of the most important members of the court at Avignon, when the deputation from Rome, with that eloquent young plebeian as its interpreter, appeared before the Pope. We may imagine that its first great success, and the pleasure which the Pope took in the conversation of Cola, must have happened during some temporary absence of the Cardinal, whose interest in the affairs of his native city would be undoubted. And it was natural that he should be a little scornful of the ambassadors of the people, and of the orator who was the son of Rienzo of the wine-shop, and very indignant at the account given by the advocate of lo Popolo, of the barons and their behaviour. The Colonna were, in fact, the least tyrannical of the tyrants; they were the noblest of all the Roman houses, and no doubt the public sentiment against the nobles in general might sometimes do a more enlightened family wrong. Certainly it is hard to reconcile the pictures of this house as given by Petrarch with the cruel tyranny of which all the nobles were accused. This no doubt was the reason why, after the triumph of that letter, the consent of the Pope to the prayer of the citizens, and his interest in Cola's tale and descriptions, the young orator fell under the shadow of courtly displeasure, and after that intoxication of victory suffered all those pangs of neglect which so often end the temporary triumph of a success at court. The story is all vague, and we have no explanation why he should have lingered on in Avignon, unless perhaps with hopes of advancement founded on that evanescent favour, or perhaps in consequence of his illness. There is a forlorn touch in the description of the chronicler that "he lay like a snake in the sun," which is full of suggestion. The reader seems to see him hanging about the precincts of the court under the stately walls of the vast Papal palace, which now stands in gloomy greatness, absorbing all the light out of the landscape. It was new then, and glorious like a heavenly palace; and sick and sad, disappointed and discouraged, the young envoy, lately so dazzled by the sunshine of favour, would no doubt haunt the great doorway, seeking a sunny spot to keep himself warm, and waiting upon Providence. Probably the Cardinal, sweeping out and in, in his state, might perceive the young Roman fallen from his temporary triumph, and be touched by pity for the orator who after all had done no harm with his pleading; for was not Stefano Colonna again, in spite of all, Senator of Rome? Let us hope that the companion at his elbow, the poet who formed part of his household, and who probably had heard, too, and admired, like Pope Clement, the parole ornate of the speaker, who, though so foolish as to assail with his eloquent tongue the nobles of the land, need not after all be left to perish on that account—was the person who pointed out to his patron the poor fellow in his cloak, shivering in the mistral, that chill wind unknown in the midlands of Italy. It is certain that Petrarch here made Cola's acquaintance, and that Cardinal Colonna, remorseful to see the misery he had caused, took trouble to have his young countryman restored to favour, and procured him the appointment of Notary of the city, with which Cola returned to Rome—"fra i denti minacciava," says his biographer, swearing between his teeth.

It was in 1344 that his promotion took place, and for some years after Cola performed the duties of his office cortesemente, with courtesy, the highest praise an Italian of his time could give. In this occupation he had boundless opportunities of studying more closely the system of government which had resumed its full sway under the old familiar succession of Senators, generally a Colonna and an Orsini. "He saw and knew," says the chronicler, himself growing vehement in the excitement of the subject, "the robbery of those dogs of the Capitol, the cruelty and injustice of those in power. In all the commune he did not find one good citizen who would render help." It would seem, though there is here little aid of dates, that he did not act precipitately, but, probably with the hope of being able himself to do something to remedy matters, kept silence while his heart burned, as long as silence was possible. But the moment came when he could do so no longer, and the little scene at the meeting of the Cammora, the City Council, stands out as clearly before us as if it had been a municipal assembly of the present day. We are not told what special question was before the meeting which proved the last straw of the burden of indignation and impatience which Cola at his table, writing with the silver pen which he thought more worthy than a goose quill for the dignity of his office, had to bear. (One wonders if he was the inventor, without knowing it, of that little instrument, the artificial pen of metal with which, chiefly, literature is manufactured in our days? But silver is too soft and ductile to have ever become popular, and though very suitable to pour forth those mellifluous sentences in which the young spokesman of the Romans wrote to his chiefs from Avignon, would scarcely answer for the sterner purposes of the council to inscribe punishments or calculate fines withal.) One day, however, sitting in his place, writing down the decrees for those fines and penalties, sudden wrath seized upon the young scribe who already had called himself the consul of widows and orphans, and of the poor.

"One day during a discussion on the subject of the taxes of Rome, he rose to his feet among all the Councillors and said, 'You are not good citizens, you who suck the blood of the poor and will not give them any help.' Then he admonished the officials and the Rectors that they ought rather to provide for the good government, lo buono stato, of their city of Rome. When the impetuous address of Cola di Rienzi was ended, one of the Colonna, who was called Andreozzo di Normanno, the Camarlengo, got up and struck him a ringing blow on the cheek: and another who was the Secretary of the Senate, Tomma de Fortifiocca, mocked him with an insulting sign. This was the end of their talking."

We hear of no more remonstrances in the council. It is said that Cola was not a brave man, though we have so many proofs of courage afterwards that it is difficult to believe him to have been lacking in this particular. At all events he went out from that selfish and mocking assembly with his cheek tingling from the blow, and his heart burning more and more, to ponder over other means of moving the community and helping Rome.

The next incident opens up to us a curious world of surmise, and suggests to the imagination much that is unknown, in the lower regions of art, a crowd of secondary performers in that arena, the unknown painters, the half-workmen, half-artists, who form a background wherever a school of art exists. Cola perhaps may have had relations with some of these half-developed artists, not sufficiently advanced to paint an altar-piece, the scholars or lesser brethren of some local bottega. There was little native art at any time in Rome. The ancient and but dimly recorded work of the Cosimati, the only Roman school, is lost in the mists, and was over and ended in the fourteenth century. But there must have been some humble survival of trained workmen capable at least of mural decorations if no more. Pondering long how to reach the public, Cola seems to have bethought himself of this humble instrument of art. As we do not hear before of any such method of instructing the people, we may be allowed to suppose it was his invention as well as the silver pen. His active brain was buzzing with new things in every way, both great and small, and this was the first device he hit upon. Even the poorest art must have been of use in the absence of books for the illustration of sacred story and the instruction of the ignorant, and it was at this kind of instantaneous effect that Cola aimed. He had the confidence of the visionary that the evil state of affairs needed only to be known to produce instant reformation. The grievance over and over again insisted upon by his biographer, and which was the burden of his outburst in the council, was that "no one would help"—non si trovava uno buon Cittatino, che lo volesse adjutare. Did they but know, the common people, how they were oppressed, and the nobles what oppressors they were, it was surely certain that every one would help, and that all would go right, and the buono stato be established once more.

Here is the strange way in which Cola for the first time publicly "admonished the rectors and the people to do well, by a similitude."

"A similitude," says his biographer, "which he caused to be painted on the palace of the Capitol in front of the market, on the wall above the Cammora (Council Chamber). Here was painted an allegory in the following form—namely, a great sea with horrible waves, and much disturbed. In the midst of this sea was a ship, almost wrecked, without helm or sails. In this ship, in great peril, was a woman, a widow, clothed in black, bound with a girdle of sadness, her face disfigured, her hair floating wildly, as if she would have wept. She was kneeling, her hands crossed, beating her breast and ready to perish. The superscription over her was This is Rome. Round this ship were four other ships wrecked: their sails torn away, their oars broken, their rudders lost. In each one was a woman smothered and dead. The first was called Babylon; the second Carthage; the third Troy; the fourth Jerusalem. Written above was: These cities by injustice perished and came to nothing. A label proceeding from the women dead bore the lines:

'Once were we raised o'er lords and rulers all,

And now we wait, Oh Rome, to see thee fall.'

"On the left hand were two islands: on one of these was a woman sitting shamefaced with an inscription over her This is Italy. And she spoke and said:

'Once had'st thou power o'er every land,

I only now, thy sister, hold thy hand.'

"On the other island were four women, with their hands at their throats, kneeling on their knees, in great sadness, and speaking thus:

'By many virtues once accompanied

Thou on the sea goest now abandonëd.'

"These were the four Cardinal virtues, Temperance, Justice, Prudence and Fortitude. On the other side was another little isle, and on this islet was a woman kneeling, her hands stretched out to heaven as if she prayed. She was clothed in white and her name was Christian Faith: and this is what her verse said:

'Oh noblest Father, lord and leader mine,

Where shall I be if Rome sink and decline?'

"Above on the right of the picture were four kinds of winged creatures who breathed and blew upon the sea, creating a storm and driving the sinking ship that it might perish. The first order were Lions, Wolves, and Bears, and were thus labelled: These are the powerful Barons and the wicked Officials. The second order were Dogs, Pigs, and Goats, and over them was written: These are the evil counsellors, the followers of the nobles. The third order were Sheep, Goats, and Foxes, and the label: These are the false officials, Judges and Notaries. The fourth order were Hares, Cats, and Monkeys, and their label: These are the People, Thieves, Murderers, Adulterers, and Spoilers of Men. Above was the sky: in the midst the Majesty Divine as though coming to Judgment, two swords coming from His mouth. On one side stood St. Peter, and on the other St. Paul praying. When the people saw this similitude with these figures every one marvelled."

Who painted this strange allegory, and how the work could be done in secret, in such a public place, so as to be suddenly revealed as a surprise to the astonished crowd, we have no means of knowing. It would be, no doubt, of the rudest art, probably such a scroll as might be printed off in a hundred examples and pasted on the walls by our readier methods, not much above the original drawings of our pavements. We can imagine the simplicity of the symbolism, the agitated sea in curved lines, the galleys dropping out of the picture, the symbolical figures with their mottoes. The painting must have been executed by the light of early dawn, or under cover of some license to which Cola himself as an official had a right, perhaps behind the veil of a scaffolding—put up on some pretence of necessary repairs: and suddenly blazing forth upon the people in the brightness of the morning, when the early life of Rome began again, and suitors and litigants began to cluster on the great steps, each with his private grievance, his lawsuit or complaint. What a sensation must that have occasioned as gazer after gazer caught sight of the fresh colours glowing on what was a blank wall the day before! The strange inscriptions in their doggerel lines, mystic enough to pique every intelligence, simple enough to be comprehensible by the crowd, would be read by one and another to show their learning over the heads of the multitude. How strange a thing, catching every eye! No doubt the plan of it, so unusual an appeal to the popular understanding, was Cola's; but who could the artist be who painted that "similitude"? Not any one, we should suppose, who lived to make a name for himself—as indeed, so far as we know, there were none such in Rome.

This pictorial instruction was for the poor: it placed before them Rome, their city, for love of which they were always capable of being roused to at least a temporary enthusiasm—struggling and unhappy, cheated by those she most trusted, ravaged by small and great, in danger of final and hopeless shipwreck. In all her ancient greatness, the peer and sister of the splendid cities of the antique world, and like them falling into a ruin which in her case might yet be avoided, the suggestion was one which was admirably fitted to stir and move the spectators, all of them proud of the name of Roman, and deeply conscious of ill-government and suffering. This, however, was but one side of the work which he had set himself to do. A short time after, when his picture had become the subject of all tongues in Rome, Cola the notary invited the nobles and notables of the city to meet in the Church of St. John Lateran to hear him expound a certain inscription there which had hitherto (we are told) baffled all interpreters. It must be supposed that he stood high in the favour of the Church, and of Raymond the Bishop of Orvieto, the Pope's representative, or he would scarcely have been permitted to use the great basilica for such a purpose.

The Church of the Lateran, however, as we know from various sources, was in an almost ruined state, nearly roofless and probably, in consequence, open to invasions of such a kind. Cola must have already secured the attention of Rome in all circles, notwithstanding that box on the ear with which Andreozzo of the Colonna had tried to silence him. He was taken by some for a burlatore, a man who was a great jest and out of whom much amusement could be got; and this was the aspect in which he appeared to one portion of society, to the young barons and gilded youth of Rome—a delusion to which he would seem to have temporarily lent himself, in order to diffuse his doctrine; while the more serious part of the aristocracy seem to have become curious at least to hear what he had to say, and prescient of meanings in him which it would be well to keep in order by better means than the simple method of Andreozzo. The working of Cola's own mind it is less easy to trace. His picture had been such an allegory as the age loved, broad enough and simple enough at the same time to reach the common level of understanding. When he addressed himself to the higher class, it was with an instinctive sense of the difference, but without perhaps a very clear perception what that difference was, or how to bear himself before this novel audience. Perhaps he was right in believing that a striking spectacle was the best thing to startle the aristocrats into attention: perhaps he thought it well to take advantage of the notion that Cola of Rienzo was more or less a buffoon, and that a speech of his was likely to be amusing whatever else it might be. The dress which his biographer describes minutely, and which had evidently been very carefully prepared, seems to favour this idea.

"Not much time passed (after the exhibition of the picture) before he admonished the people by a fine sermon in the vulgar tongue, which he made in St. John Lateran. On the wall behind the choir, he had fixed a great and magnificent plate of metal inscribed with ancient letters, which none could read or interpret except he alone. Round this tablet he had caused several figures to be painted which represented the Senate of Rome conceding the authority over the city to the Emperor Vespasian. In the midst of the Church was erected a platform (un parlatorio) with seats upon it, covered with carpets and curtains—and upon this were gathered many great personages, among whom were Stefano Colonna, and Giovanni Colonna his son, who were the greatest and most magnificent in the city. There were also many wise and learned men, Judges and Decretalists, and many persons of authority. Cola di Rienzo came upon the stage among these great people. He was dressed in a tunic and cape after the German fashion, with a hood up to his throat in fine white cloth, and a little white cap on his head. On the round of his cap were crowns of gold, the one in the front being divided by a sword made in silver, the point of which was stuck through the crown. He came out very boldly, and when silence was procured he made a fine sermon with many beautiful words, and said that Rome was beaten down and lay on the ground, and could not see where she lay, for her eyes were torn out of her head. Her eyes were the Pope and the Emperor, both of whom Rome had lost by the wickedness of her citizens. Then he said (pointing to the pictured figures), 'Behold, what was the magnificence of the Senate when it gave the authority to the Emperor.' He then read a paper in which was written the interpretation of the inscription, which was the act by which the imperial power was given by the people of Rome to Vespasian. Firstly that Vespasian should have the power to make good laws, and to make alliances with any whom he pleased, and that he should be entitled to increase or diminish the garden of Rome, that is Italy: and that he should give accounts less or more as he would. He might also raise men to be dukes and kings, put them up or pull them down, destroy or rebuild cities, divert rivers out of their beds to flow in another channel, put on taxes or abolish them at his pleasure. All these things the Romans gave to Vespasian according to their Charter to which Tiberius Cæsar consented. He then put aside that paper and said, 'Sirs, such was the majesty of the people of Rome that it was they who conferred this authority upon the Emperor. Now they have lost it altogether.' Then he entered more fully into the question and said, 'Romans, you do not live in peace: your lands are not cultivated. The Jubilee is approaching and you have no provision of grain or food for the people who are coming, who will find themselves unprovided for, and who will take up stones in the rage of their hunger: but neither will the stones be enough for such a multitude.' Then concluding he added: 'I pray you keep the peace.' Then he said this parable: 'Sirs, I know that many people make a mock at me for what I do and say. And why? For envy. But I thank God there are three things which consume the slanderers. The first luxury, the second jealousy, the third envy.' When he had ended the sermon and come down, he was much lauded by the people."

The inscription thus set before the people was the bronze table, called the Lex Regia. Why it was that no one had been able to interpret