CHAPTER IV.

DECLINE AND FALL.

After so strange and so complete a victory over one party, had the Tribune pushed his advantage, and gone against the other with all the prestige of his triumph, he would in all probability have ended the resistance of the nobles altogether. But he did not do this. He had no desire for any more fighting. It is supposed, with insufficient reason we think, that personally he was a coward. What is more likely is that so sensitive and nervous a man (to use the jargon of our own times) must have suffered, as any fine temperament would have done, from that scene at the gate of San Lorenzo, and poor young Janni Colonna lying in his blood; and that when he declared "he would draw his sword no more," he did so with a sincere disgust for all such brutal methods. His own ways of convincing people were by argument and elocution, and pictures on the walls, which, if they did not convince, did nobody any harm. The next scene, however, which he prepared for his audience does not look much like the horror for which we have given him credit. He had informed his followers before he first set out against the nobles that he was taking his son with him—something in the tone with which the presence of a Prince Imperial might be proclaimed to an army; and we now find the young Lorenzo placed still more in the foreground. The day after that dreadful victory Cola called together the militia of the city by the most touching argument. "Come with me," he said, "and afterwards you shall have your pay." They turned out accordingly to accompany him, wondering, but not knowing what he had in his mind.

"The trumpets sounded at the place where the fight (sconfitto) had taken place. No one knew what was to be done there. He went with his son to the very spot where Stefano Colonna had died. There was still there a little pool of water. Cola made his son dismount and threw over him the water which was still tinged with the blood of Stefano, and said to him: 'Be thou a Knight of Victory.' All around wondered and were stupefied. Then he gave orders that all the commanders should strike his son on the shoulder with their swords. This done he returned to the Capitol, and said: 'Go your ways. We have done a common work. All our sires were Romans, the country expects that we should fight for her.' When this was said the minds of the people were much exercised, and some would never bear arms again. Then the Tribune began to be greatly hated, and people began to talk among themselves of his arrogance which was not small."

This grotesque and horrible ceremony seems to have done Cola more harm than all that had gone before. The leader of a revolution should have no sons. The excellent instinct of providing for his family after him, and making himself a stepping stone for his children, though proceeding from "what is best within the soul," has spoiled many a history. Cola di Rienzi was a most conspicuous and might have been a great man: but Rienzo di Cola, which would have been his son's natural name, was nobody, and is never heard of after this terrible baptism of blood, so abhorrent to every natural and generous impulse. Did the gazers in the streets see the specks of red on young Lorenzo's dress as he rode along through the city from the Tiburtine gate, and through the Forum to the Capitol, where all the train was dismissed so summarily? As the Cavallerotti, the better part of the gathering, turned their horses and rode away offended, no doubt the news ran through quarter after quarter with them. The blood of Stefanello, the heir of great Colonna! And thoughts of the old man desolate, and of young Janni so brave and gay, would come into many a mind. They might be tyrants, but they were familiar Roman faces, known to all, and with some reason to be proud, if proud they were; not like this upstart, who called honest men away from their own concerns to do honour to his low-born son, and sent them packing about their business afterwards without so much as a dinner to celebrate the new knight!

This was all in November, the 20th and 21st: and it was on the 20th of May that Cola had received his election upon the Capitol and been proclaimed master of the destinies of the universe, by inference, as master of Rome. Six months, no more, crammed full of gorgeous pageants and exciting events. Then, notwithstanding the extraordinary character of his revolution, he had been believed in, and encouraged by all around. He had received the sanction of the Pope, the friendly congratulations of the great Italian towns, and above all the applause, enthusiastic and overflowing, of Petrarch the greatest of living poets. By degrees all these sympathies and applauses had fallen from him. Florence and the other great cities had withdrawn their friendship, the Pope had cancelled his commission, the Pope's Vicar had left the Tribune's side. The more his vanity and self-admiration grew, the more his friends had fallen from him. That very day—the day after the defeat of the Colonna, before the news could have reached any one at a distance, Petrarch on his way to Italy, partly brought back thither by anxiety about his friend, received from another friend a copy of one of the arrogant and extraordinary letters which Cola was sending about the world, and read and re-read it and was stupefied. "What answer can be made to it? I know not," he cries. "I see that fate pursues the country, and on whatever side I turn, I find subjects of grief and trouble. If Rome is ruined what hope remains for Italy? and if Italy is degraded what will become of me? What can I offer but tears?" A few days later, arrived at Genoa, the poet wrote to Rienzi himself in reproof and sorrow:

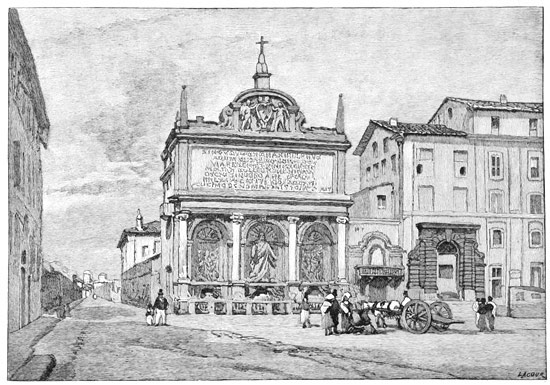

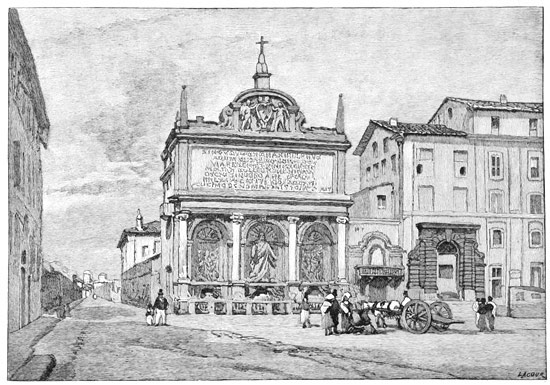

AQUA FELICE

To face page 462.

"Often, I confess it, I have had occasion upon thy account to repeat with immense joy what Cicero puts in the mouth of Scipio Africanus:—'What is this great and delightful sound that comes to my ears?' And certainly nothing could be better applied to the splendour of thy name and to the frequent and joyful account of thy doings: and it was indeed good to my heart to speak to thee in that exhortation, full of thy praise and of encouragements to continue, which I sent thee. Deh! do nothing, I conjure thee, to make me now ask, whence is this great and fatal rumour which strikes my ear so painfully? Take care, I beseech thee, not thyself to soil thine own splendid fame. No man in the world except thyself can shake the foundations of the edifice thou hast constructed; but that which thou hast founded thou canst ruin: for to destroy his own proper work no man is so able as the architect. You know the road by which you have risen to glory: if you turn back you shall soon find yourself in the lowest place; and going down is naturally the quicker.... I was hastening to you and with all my heart: but I turn upon the way. Other than what you were, I would not see you. Adieu, Rome, to thee also adieu, if that is true which I have heard. Rather than come to thee I would go to the Indies, to the end of the world.... Oh, how ill the beginning agrees with the end! Oh, miserable ears of mine that, accustomed to the sound of glory, do not know how to bear such announcements of shame! But may not these be lies and my words false? Oh that it might be so! How glad should I be to confess my error!... If thou art indeed so little careful of thy fame, think at least of mine. You well know by what tremendous tempest I am threatened, how many are the crowd of faultfinders ready to ruin me. While there is still time put your mind to it, be vigilant, look well to what you do, guide yourself continually by good counsel, consider with yourself, not deceiving yourself, what you are, what you were, from whence you have come, and to what point, without detriment to the public weal, you can attain: how to attire yourself, what name to assume, what hopes to awaken, and of what doctrine to make open confession; understanding always that not Lord, but solely Minister, you are of the Republic."

The share which Petrarch thus takes to himself in Cola's fortunes may seem exaggerated; but it must be remembered that the Colonna were his chief patrons and friends, that it was under their protecting shadow that he had risen to fame, and that his warm friendship for Rienzi had already deeply affected the terms of his relationship with them. That relationship had come to a positive breach so far as his most powerful protector, the Cardinal Giovanni, was concerned, a breach of feeling on one side as well as of protection on the other. His letter to the Cardinal after this catastrophe, condoling with him upon the death of his brothers, is one of the coldest of compositions, very unlike the warm and eager affection of old, and consisting chiefly of elaborate apologies for not having written. The poet had completely committed himself in respect to the Tribune; he had hailed his advent in the most enthusiastic terms, he had proclaimed him the hope of Italy, he had staked his own reputation upon his friend's disinterestedness and patriotism; therefore this downfall with all its humiliating circumstances, the vanities and self-intoxication which had brought it about, were intolerable to Petrarch: his own credit as well as Cola's was concerned. He had been so rash as to answer for the Tribune in all quarters, to pledge his own judgment, his power of understanding men, almost his honour, on Cola's behalf; and to be proved so wrong, so little capable of estimating justly the man whom he believed himself to know so well, was bitterness unspeakable to him.

The interest of his tragic disappointment and sorrow is at the same time enhanced by the fact, that the other party to this dreadful quarrel had been the constant objects of the poet's eulogies and enthusiasm. It is to Petrarch that we owe most of our knowledge of the Colonna family at this remarkable period of a long history which is filled with the oft-repeated incidents of an endless struggle for power, either with the rebellious Romans themselves, or with the other little less great family of the Orsini who, unfortunately for themselves, had no Petrarch to bring them fully into the light of day. The many allusions in Petrarch's letters, his reminiscences of the ample and gracious household, all so friendly, and caressing, all of one mind as to his own poetical qualities, and anxious to heap honours upon him, light up for us the face of the much complicated story, and give interest to many an elaborate poetical or philosophical disquisition. Especially the figure of the father, the old Stefano with his seven sons and the innumerable tribe of nephews and cousins, not to say grandsons, still more cherished, who surrounded him—rises clear, magnanimous, out of the disturbed and stormy landscape. His brief appearances in the chronicle which we have quoted, with a keen brief speech here and there, imperative, in strong accents of common sense as well as of power, add a touch of energetic life to the many anecdotes and descriptions of a more elaborate kind. And the poet would seem never to have failed in his admiration for the old Magnanimo. At an earlier period he had described in several letters to the son Giovanni, the Cardinal, the reception given to him at Rome, and conversations, some of them very remarkable. One scene above all, of which Petrarch reminds Stefano himself in his bereavement, gives us a most touching picture of the noble old man.

"One day at sunset you and I alone were walking by that spacious way which leads from your house to the Capitol, when we paused at that point where it is crossed by the other road by which on one hand you ascend to the Arch of Camillus, and on the other go down to the Tiber: we paused there without interruption from any and talked together of the condition of your house and family, which, often assailed by the enmity of strangers, was at that time moved by grievous internal commotions:—when the discourse fell upon one of your sons with whom, more by the work of scandal-mongers than by paternal resentment, you were angry, and by your goodness it was given to me, what many others had not been able to obtain, to persuade you to receive him again to your good grace. After you had lamented his faults to me, changing your aspect all at once you said (I remember not only the substance of your discourse but the very words). 'This son of mine, thy friend, whom, thanks to thee, I will now receive again with paternal affection, has vomited forth words concerning my old age, of which it is best to be silent; but since I cannot refuse you, let us put a stone over the past and let a full amnesty, as people say, be conceded. From my lips I promise thee, not another word shall be heard.

"'One thing I will tell you, that you may make perpetual remembrance of it. It is made a reproach to my old age that I am mixed up with warlike factions more than is becoming, and more than there is any occasion, and that thus I will leave to my sons an inheritance of peril and hate. But as God is true, I desire you to believe that for love of peace alone I allow myself to be drawn into war. Whether it be the effect of my extreme old age which chills and enfeebles the spirit in this already stony bosom, or whether it proceeds from my long observation of human affairs, it is certain that more than others I am greedy of repose and peace. But fixed and immovable as is my resolution never to shrink from trouble though I may prefer a settled and tranquil life, I find it better, since fate compels me, to go down to the sepulchre fighting, than to submit, old as I am, to servitude. And for what you say of my heirs I have but one thing to reply. Listen well, and fix my words in your mind. God grant that I may leave my inheritance to my sons. But all in opposition to my desires are the decrees of fate (the words were said with tears): contrary to the order of nature it is I who shall be the heir of all my sons.' And thus saying, your eyes swollen with tears, you turned away."

At the corner where the Corso is crossed by the street which borders the Forum of Trajan, let whoso will pause amid the bustle of modern traffic and think for a moment of those two figures standing together talking, "without interruption from any one," in the middle of that open space, while the long level rays of the sunset streamed upon them from beyond the Flaminian gate. Was there some great popular meeting at the Capitol which had cleared the streets, the hum of voices rising on the height, but all quiet here at this dangerous, glorious hour, when fever is abroad and the women and children are all indoors? "I made light of it, I confess," says Petrarch, though he acknowledges that he told the story of this dreadful presentiment to the Cardinal, who, sighing, exclaimed, "Would to God that my father's prediction may not come true!" But old Stefano with his weight of years upon him, and his front like Jove, turned away sighing, stroking his venerable beard, unmoved by the poet's reassurances, with that terrible conviction in his heart. They were all young and he old: daring, careless young men, laughing at that same Cola of the little albergo, the son of the wine-shop, who said he was to be an emperor. But the shadow on the grandsire's heart was one of those which events cast before them. Young Janni was to go among the first, the brave boy who ought to have been heir of all. To him, too, his grandfather, the great Stefano, the head of the full house, was to be heir.

The terrible event of the Porta di San Lorenzo shows in still darker colours when we look at it closer. Stefano, the son of Stefano, and Janni his son, are the two most conspicuous names: but there were more. Camillo, figlio naturale, morto il 20 November 1347, all'assalto di Porta San Lorenzo; Pietro, figlio naturale, rimase occiso a Porta San Lorenzo. Giovanni of Agapito, Pietro of Agapito, nephews of old Stefano, morti nell'assalto di Porta San Lorenzo. Seven in all were the scions of Colonna who ended their life that horrible November morning in the mud and rain; or more dreadful still under the morning sun which broke out so suddenly, showing those white dreadful forms all stripped and abandoned, upon the fatal way. It was little wonder if between the house of Colonna and the upstart Cola no peace should ever be possible after a lost battle so fatal and so humiliating to the race.

Perhaps after the first moment of terrible joy and relief to find himself uninjured, and his enemies so deeply punished, compunction seized the sensitive mind of Cola: or perhaps he was alarmed by the displeasure of the Pope, his abandonment by all his friends, and the solemn adjuration of Petrarch. It is certain that after this he dropped many of his pretensions, subdued the fantastic arrogance of his titles and superscription, gave up his claim to elect emperors and preside over the fortunes of the world, and began to devote himself with humility to the government of the city which had fallen into something of its old disorderliness within the walls; while outside there was again, as of old, no security at all. The rebel barons had resumed their turbulent sway, the robbers reappeared in all their old coverts; and once again every road to Rome was as unsafe as that on which the traveller of old fell among thieves. Cola, Knight and Lieutenant of our Lord the Pope, now headed his proclamations, instead of Nicolas, severe and clement. His crown of silver and sceptre of steel, fantastic emblems, were hung up before the shrine of Our Lady in the Ara Cœli, and everything about him was toned down into gravity. By this means he kept up a semblance of peace, and replaced the Buono Stato in its visionary shrine. But Cola had gone too far, and lost the confidence of the people too completely to rise again. His very humility would no doubt be against him, showing the weakness which a man unsupported on any side should perhaps have been bold enough to defy, hardihood being now his only chance in face of so many assailants. Pope Clement thundered against him from Avignon; the nobles lay in Palestrina and Marino, and many a smaller fortress besides, irreconcilable, watching every opportunity of assailing him. The country was once more devastated all round Rome, provisions short, corn dear, and funds failing as well as authority and respect. And Cola's heart had failed him along with his prosperity. He had bad dreams; he himself tells the story of this moral downfall with a forlorn attempt to show that it was not, after all, his visible enemies, or the power of men, which had cast him down.

"After my triumph over the Colonna," he writes, "just when my dominion seemed strongest, my stoutness of heart was taken from me, and I was seized by visionary terrors. Night after night awakened by visions and dreams I cried out, 'The Capitol is falling,' or 'The enemy comes!' For some time an owl alighted every night on the summit of the Capitol, and though chased away by my servants always came back again. For twelve nights this took my sleep and all quiet of mind from me. It was thus that dreams and nightbirds tormented one who had not been afraid of the fury of the Roman nobles, nor terrified by armies of armed men."

The brag was a forlorn one, but it was all of which the fallen Tribune was now capable. Cola received back the Vicar of the Pope, who probably was not without some affection for his old triumphant colleague, with gladness and humility, and seated that representative of ecclesiastical authority beside himself in his chair of judgment, before which he no longer summoned the princes and great ones of the earth. The end came in an unexpected way, of which the writer of the Vita gives the popular account: it is a little different from that of the graver history but only in details. A certain Pepino, Count Palatine of Altamura, a fugitive from Naples, whose object in Rome was to enlist soldiers for the service of Louis of Hungary, then eager to avenge the murder of his brother Andrew, the husband of Queen Joan of Naples—had taken up his abode in the city. He was in league with several of the nobles, and ready to lend a hand in any available way against the Tribune. Fearing to be brought before the tribunal of Cola, and to be obliged to explain the object of his residence in Rome, he shut himself up in his palace and made an effort to raise the city against its head.

"Messer the Conte Paladino at this time threw a bar (barricade) across the street, under the Arch of Salvator (to defend his quarters apparently). A night and a day the bells of St. Angelo in Pescheria rang a stuormo, but no one attempted to break down the bar. The Tribune sent a party of horsemen against the bar, and an officer named Scarpetta, wounded by a lance, fell dead in the skirmish. When the Tribune heard that Scarpetta was dead and that the people were not affected by the sound of the tocsin, although the bell of St. Angelo continued to ring, he sighed deeply: chilled by alarm he wept: he knew not what to do. His heart was beaten down and brought low. He had not the courage of a child. Scarcely could he speak. He believed that ambushes were laid for him in the city, which was not true, for there was as yet no open rebellion: no one, as yet, had risen against the Tribune. But their zeal had become cold: and he believed that he would be killed. What can be said more? He knew he had not the courage to die in the service of the people as he had promised. Weeping and sighing, he addressed as many as were there, saying that he had done well, but that from envy the people were not content with him. 'Now in the seventh month am I driven from my dominion.' Having said these words weeping, he mounted his horse and sounded the silver trumpets, and bearing the imperial insignia, accompanied by armed men, he came down as in a triumph, and went to the Castle of St. Angelo, and there shut himself in. His wife, disguised in the habit of a monk, came from the Palazzo de Lalli. When the Tribune descended from his greatness the others also wept who were with him, and the miserable people wept. His chamber was found to be full of many beautiful things, and so many letters were found there that you would not believe it. The barons heard of this downfall, but three days passed before they returned to Rome because of their fear. Even when they had come back fear was in their hearts. They made a picture of the Tribune on the wall of the Capitol, as if he were riding, but with his head down and his feet above. They also painted Cecco Manneo, who was his Notary and Chancellor, and Conte, his nephew, who held the castle of Civita Vecchia. Then the Cardinal Legate entered into Rome, and proceeded against him and distributed the greater part of his goods, and proclaimed him to be a heretic."

Thus suddenly Cola fell, as he had risen. His heart had failed him without reason or necessity, for the city had not shown any open signs of rebellion, and there seems to have been no reason why he should have fled to St. Angelo. The people, though they did not respond to his call to arms, took no more notice of the tocsin of his opponent or of his cry of Death to the Tribune. Rome lay silent pondering many things, caring little how the tide turned, perhaps, with the instinct of Lo Popolo everywhere, thinking that a change might be a good thing: but it was no overt act on the part of the populace which drove its idol away. The act was entirely his own—his heart had failed him. In these days we should say his nerves had broken down. The phraseology is different, but the things were the same. His downfall, however, was not perhaps quite so sudden in reality as it appears in the chronicle. It would seem that he endeavoured to escape to Civita Vecchia where his nephew was governor, but was not received there, and had to come back to Rome, and hide his head once more for a short time in St. Angelo. But it is certain that before the end of January, 1438, he had finally disappeared, a shamed and nameless man, his titles abolished, his property divided among his enemies. Never was a downfall more sudden or more complete.

Stefano Colonna and his friends re-entered Rome with little appearance of triumph. The remembrance of the Porta San Lorenzo was too recent for rejoicings, and it must be put to the credit of the old chief, bereaved and sorrowful, that no reprisals were made, that a general amnesty was proclaimed, and the peace of the city preserved. Cola's family, at least for the time, remained peaceably at Rome, and met with no harm. We hear nothing of the unfortunate young Knight of Victory who had been sprinkled with the blood of the Colonnas. The Tribune went down like a stone, and for the moment, of him who had filled men's mouths and minds with so many strange tidings, there was no more to tell.

Cola's absence from Rome lasted for seven years; of which time there is no mention whatever in the Vita, which concerns itself exclusively with things that happened in Rome; but his steps can be very clearly traced. We never again find our enthusiast, he who first ascended the Capitol in a passion of disinterested zeal and patriotism, approved by every honest visionary and every suffering citizen, a man chosen of God to deliver the city. That his motives were ever ill motives, or that he had begun to seek his own prosperity alone, it would be hard to say: but he appears to us henceforward in a changed aspect as the eager conspirator, the commonplace plotter and schemer, hungry for glory and plunder, and using every means, by hook or by crook, to recover what he has lost, which is a far more familiar figure than the ideal Reformer, the disinterested revolutionary. We meet with that vulgar hero a hundred times in the stormy record of Italian politics, a man without scruples, sticking at nothing. But Rienzi was of a different nature: he was at once a less and a greater sinner. It would be unjustifiable to say that he ever gave up the thought of the Buono Stato, or ceased to desire the welfare of Rome. But in the long interval of his disappearance from the scene, he not only plotted like the other, but used that higher motive, and the mystic elements that were in the air, and the tendency towards all that was occult, and much that was noble in the aspirations of the visionaries of his time, to further the one object, his return to power, to the Capitol, and to the dominion of Rome. A conspirator is the commonplace of Italian story, at every period: and the pretender, catching at every straw to get back to his unsteady throne, besieging every potentate that can help him, pleading every inducement from the highest to the lowest—self-interest, philanthropy, the service of God, the most generous and the meanest sentiments—is also a very well known figure; but it is rare to find a man truly affected by the most mystic teachings of religion, yet pressing them also into his service, and making use of what he conceives to be the impulses of the Holy Spirit for the furtherance of his private ends, without, nevertheless, so far as can be asserted, becoming a hypocrite or insincere in the faith which he professes.

This was the strange development to which the Tribune came. After some vain attempts to awaken in the Roman territory friends who could help him, his heart broken by the fickleness and desertion of the Popolo in which he had trusted, he took refuge in the wild mountain country of the Apennines, where there existed a rude and strange religious party, aiming in the midst of the most austere devotion at a total overturn of society, and that return of a primeval age of innocence and bliss which is so seductive to the mystical mind. In the caves and dens of the earth and in the mountain villages and little convents, there dwelt a severe sect of the Franciscans, men whose love of Poverty, their founder's bride and choice, was almost stronger than their love of that founder himself. The Fraticelli were only heretics by dint of holding their Rule more strictly than the other religious of their order, and by indulging in ecstatic visions of a renovated state and a purified people—visions less personal though not less sincere or pious, than those which inflicted upon Francis himself the semblance of the wounds of the Redeemer, in that passion of pity and love which possessed his heart. The exile among them, who had himself been aroused out of the obscurity of ordinary life by a corresponding dream, found himself stimulated and inspired over again by the teaching of these visionaries. One of them, it is said, found him out in the refuge where he thought himself absolutely unknown, and, addressing him by name, told him that he had still a great career before him, and that it should be his to restore to Rome the double reign of universal dominion, to establish the Pope and the Empire in the imperial city, and reconcile for ever those two joint rulers appointed of God.

It is curious to find that what is to some extent the existing state of affairs—the junction in one place of the two monarchs of the earth—should have been the dream and hope of religious visionaries in the middle of the fourteenth century. The Emperor to them was but a glorified King of Italy, with a vague and unknown world behind him; and they believed that the Millennium would come, when that supreme sovereign on the Capitol and the Holy Father from the seat of St. Peter should sway the world at their will. The same class, in the same order now—so much as confiscation after confiscation permits that order to exist—would fight to its last gasp against the forced conjunction, which its fathers before it thus thought of as the thing most to be prayed for, and schemed for, in the whole world.

When others beside the Fraticelli discovered Rienzi's hiding-place, and he found himself, or imagined himself, in some danger, he went to Prague to seek shelter with the Emperor Charles IV., and a remarkable correspondence took place between that potentate on one side and the Archbishop of Prague, his counsellor, and Rienzi on the other, in which the exile promised many splendours to the monarch, and offered himself as his guide to Rome, and to lend him the weight of his influence there with the people over whom Rienzi believed that he would yet himself preside with greater power than ever. That Charles himself should reply to these letters, and reason the matter out with this forlorn wanderer, shows of itself what a power was in his words and in the fervour of his purpose. But it is ill talking between a great monarch and a penniless exile, and Charles seems to have felt no scruple in handing him over, after full exposition of his views, to the archbishop as a heretic. That prelate transferred him to the Pope, to be dealt with as a man already excommunicated under the ban of the Church, and now once more promulgating strange doctrines, ought to be; and thus his freedom, and his wandering, and the comparative safety of his life came to an end, and a second stage of strange development began.

The fortunes of Rienzi were at a very low ebb when he reached Avignon and fell into the hands of his enemies, of those whom he had assailed and those whom he had disappointed, at that court where there was no one to say a good word for him, and whe