CHAPTER VI.

THE END OF THE TRAGEDY.

It was in the beginning of August 1354 that Rienzi returned to Rome. Great preparations had been made for his reception. The municipal guards, with all the cavalry that were in Rome, went out as far as Monte Mario to meet him, with branches of olive in their hands, "in sign of victory and peace. The people were as joyful as if he had been Scipio Africanus," our biographer says. He came in by the gate of the Castello, near St. Angelo, and went thence direct to the centre of the city, through streets adorned with triumphal arches, hung with tapestry, resounding with acclamations.

"Great was the delight and fervour of the people. With all these honours they led him to the Palazzo of the Capitol. There he made them a beautiful and eloquent speech, in which he said that for seven years he had been absent from his house, like Nebuchadnezzar; but by the power of God he had returned to his seat and was Senator by the appointment of the Pope. He added that he meant to rectify everything and raise up the condition of Rome. The rejoicing of the Romans was as great as was that of the Jews when Jesus Christ entered Jerusalem riding upon an ass. They all honoured him, hanging out draperies and olive branches, and singing 'Blessed is he that cometh.' When all was over they returned to their homes and left him alone with his followers in the Piazza. No one offered him so much as a poor repast. The following day Cola di Rienzi received several ambassadors from the surrounding country. Deh! how well he answered. He gave replies and promises on every side. The barons remained on the watch, taking no part. The tumult of the triumph was great. Never had there been so much pomp. The infantry lined the streets. It seemed as if he meant to govern in the way of the tyrants. Most of the goods he had forfeited were restored to him. He sent out letters to all the States to declare his happy return, and he desired that every one should prepare for the Buono Stato. This man was greatly changed from his former ways. It had been his habit to be sober, temperate, abstinent. Now he became an excessive drinker, and consumed much wine. And he became large and gross in his person. He had a paunch like a tun, triumphal, like an Abbate Asinico. He was full of flesh, red, with a long beard. His countenance was changed, his eyes were as if they were inflamed—sometimes they were red as blood."

This uncompromising picture of a man whom adversity had not improved but deteriorated, is very broad and coarse with those personalities which the mob loves. Yet his biographer does not seem to have been hostile to Rienzi. He goes on to describe how the new senator on the fourth day after his arrival sent a summons to all the barons to present themselves before him, and among others he summoned Stefanello Colonna who had been a child at the time of the dreadful rout of San Lorenzo, but was now head of the house, his noble old heart-broken grandfather being by this time happily dead. It was scarcely likely that the third Stefano should receive that summons in friendship. He seized the two messengers and threw them into prison, then after a time had the teeth of one drawn, an insulting infliction, and despatched the other to Rome to demand a ransom for them: following this up by a great raid upon the surrounding country, in which his lightly armed and flying forces "lifted" the cattle of the Romans as might have been done by the emissaries of a Highland chief. Rienzi seems to have rushed to arms, collecting a great miscellaneous gathering, "some armed, some without arms, according as time permitted" to recover the cattle. But they were misled by an artifice of the most transparent description, and stumbled on as far as Tivoli without finding any opponent. Here he was stopped by the mercenaries clamouring for their pay, which he adroitly obtained from the two young commanders, Arimbaldo and Bettrom, by representing to them that when such a difficulty arose in classical times it was met by the chief citizens who immediately subscribed what was necessary. The apparently simple-minded young men (Bettrom or Bertram having apparently got over his ill-temper) gave him 500 florins each, and so the trouble was got over for the moment, and the march towards Palestrina was resumed. But the expedition was quite futile, neither Rienzi nor the young men whom he had placed at the head of affairs knowing much about the science of war. There were dissensions in the camp, the men of Velletri having a feud with those of Tivoli; and the picture which the biographer affords us of the leaders looking on, seeing a train of cattle and provision waggons entering the town which they were by way of besieging, and inquiring innocently what it was, gives the most vivid impression of the ignorance and helplessness which reigned in the attacking party: while Stefanello Colonna, to the manner born, surrounded by old warriors and fighting for his life, defended his old towers with skill as well as desperation.

While the Romans thus lost their chances of victory and occupied themselves with that destruction of the surrounding country, which was the first word of warfare in those days—the peasants and the villages always suffering, whoever might escape—there was news brought to Rienzi's camp of the arrival in Rome of the terrible Fra Moreale himself, who had arrived in all confidence, with but a small party in his train, in the city for which his brothers were fighting and in which his money formed the only treasury of war. He was a bold man and used to danger; but it did not seem that any idea of danger had occurred to him. There had been whispers among the mercenaries that the great Captain entertained no amiable feelings towards the Senator who had beguiled his young brothers into this dubious warfare: and this report would seem to have come to Rienzi's ears: but that Fra Moreale stood in any danger from Rienzi does not seem to have occurred to any spectator.

One pauses here with a wondering inquiry what were his motives at this crisis of his life. Were they simply those of the ordinary and vulgar villain, "Let us kill him that the inheritance may be ours"?—was he terrified by the prospect of the inquiries which the experienced man of war would certainly make as to the manner in which his brothers had been treated by the leader who had attained such absolute power over them? or is it possible that the patriotism, the enthusiasm for Italy, the high regard for the common weal which had once existed in the bosom of Cola di Rienzi flashed up now in his mind, in one last and tremendous flame of righteous wrath? No one perhaps so dangerous to the permanent freedom and well-being of Italy existed as this Provençal with his great army, which held allegiance to no leader but himself—without country, without creed or scruple—which he led about at his pleasure, flinging it now into one, now into the other scale. The Grande Compagnia was the terror of the whole Continent. Except that it was certain to bring disaster wherever it went, its movements were never to be calculated upon. Whatever fluctuations there might be in state or city, this roving army was always on the side of evil; it lived by fighting and disaster alone; and to drive it out of the country, out of the world if possible, would have been the most true and noble act of deliverance which could have been accomplished. Was this the purpose that flashed into Rienzi's eyes when he heard that the head of this terror, the great brigand chief and captain, had trusted himself within the walls of Rome? With the philosophy of compromise which rules among us, and which forbids us to allow an uncomplicated motive in any man, we dare hardly say or even surmise that this was so; but we may allow some room for the mingled motives which are the pet theory of our age, and yet believe that something perhaps of this nobler impulse was in the mind of the Roman Senator, who, notwithstanding his decadence and his downfall, was still the same man who by sheer enthusiasm and generous wrath, without a blow struck, had once driven its petty tyrants out of the city. Whatever may be the judgment of the reader in this respect, it is clear that Rienzi dropped the siege of Palestrina when he heard of Fra Moreale's arrival, as a dog drops a bone or an infant his toys, and hastened to Rome; while his army melted away as was usual in such wars, each band to its own country. Eight days had been passed before Palestrina, and the country round was completely devastated: but no effectual advantage had been gained when this sudden change of purpose took place.

As soon as Rienzi arrived in Rome he caused Fra Moreale to be arrested, and placed him with his brothers in the prison of the Capitol, to the great astonishment of all; but especially to the surprise of the great Captain, who thought it at first a mere expedient for extorting money, and comforted by this explanation the unfortunate brothers for whose sake he had placed himself in the snare. "Do not trouble yourselves," he said, "let me manage this affair. He shall have ten thousand, twenty thousand florins, money and people as much as he pleases." Then answered the brothers, "Deh! do so, in the name of God." They perhaps knew their Rienzi by this time, young as they were, and foolish as they had been, better than their elder and superior. And no doubt Rienzi might have made excellent terms for himself, perhaps even for Rome; but he does not seem to have entertained such an idea for a moment. When the Tribune set his foot within the gates of the city the Condottiere's fate was sealed. The biographer gives us a most curious picture of the agitation and surprise of this man in face of his fate. When he was brought to the torture (menato a lo tormento) he cried out in a consternation which is wild with foregone conclusions. "I told you what your rustic villain was," he exclaimed, as if still carrying on that discussion with the foolish young brothers. "He is going to put me to the torment! Does he not know that I am a knight? Was there ever such a clown?" Thus storming, astonished, incredulous of such a possibility, yet eager to say that he had foreseen it, the dismayed Captain was alzato, pulled up presumably by his hands as was one manner of torture, all the time murmuring and crying in his beard, half-mad and incoherent in the unexpected catastrophe. "I am Captain of the Great Company," he cried; "and being a knight I ought to be honoured. I have put the cities of Tuscany to ransom. I have laid taxes on them. I have overthrown principalities and taken the people captive." While he babbled thus in his first agony of astonishment the shadow of death closed upon Moreale, and the character of his utterances changed. He began to perceive that it was all real, and that Rienzi had now gone too far to be won by money or promises. When he was taken back to the prison which his brothers shared he told them with more dignity, that he knew he was about to die. "Gentle brothers, be not afraid," he said. "You are young; you have not felt misfortune. You shall not die, but I shall die. My life has always been full of trouble." (He was a man of sentiment, and a poet in his way, as well as a soldier of fortune.) "It was a trouble to me to live, of death I have no fear. I am glad to die where died the blessed St. Peter and St. Paul. This misadventure is thy fault, Arimbaldo; it is you who have led me into this labyrinth; but do not blame yourself or mourn for me, for I die willingly. I am a man: I have been betrayed like other men. By heaven, I was deceived! But God will have mercy upon me, I have no doubt, because I came here with a good intention." These piteous words, full to the last of astonishment, form a sort of soliloquy which runs on, broken, to the very foot of the Lion upon the great stairs, where he was led to die, amid the stormy ringing of the great bell and rushing of the people, half exultant and half terrified, who came from all quarters to see this great and terrible act of that justice to which the city in her first fervour had pledged herself. "Oh, Romans, are ye consenting to my death?" he cried. "I never did you harm; but because of your poverty and my wealth I must die." The chronicler goes on reporting the last words with fascination, as if he could not refrain. There is a wildness in them, of wonder and amazement, to the last moment. "I am not well placed," he murmured, non sto bene, evidently meaning, I am not properly placed for the blow: as he seems to have changed his position several times, kneeling down and rising again. He then kissed the knife and said, "God save thee, holy justice," and making another round knelt down again. The narrative is full of life and pity; the great soldier all bewildered, his brain failing, overwhelmed with dolorous surprise, seeking the right spot to die in. "This excellent man (honestis probisque viris, in the Latin version), Fra Moreale, whose fame is in all Italy for strength and glory, was buried in the Church of the Ara Cœli," says our chronicler. His execution took place on the spot where the Lion still stands on the left hand of the great stairs. There Fra Moreale wandered in his distraction to find a comfortable place for the last blow. The association is grim enough, and others yet more appalling were soon to gather there.

This perhaps was the only step of his life in which Rienzi had the approbation of all. The Pope displayed his approval in the most practical way by confiscating all Fra Moreale's wealth, of which 60,000 gold florins were distributed among those who had suffered by him. The funds which he had in various cities were also seized, though we are told that of those in Rome Rienzi had but a small part, a certain notary having managed, by what means we are not told, to secure the larger sum. By the interposition of the Legate, the foolish Arimbaldo, whom Rienzi's fair words had so bitterly deceived, was discharged from his prison and permitted to leave Rome, but the younger brother Bettrom, or Bertram, who, so far as we see, was never a partisan of Rienzi, was left behind; and though his presence is noted at another tragic moment, we do not hear what became of him eventually. With the money he received Rienzi made haste to pay his soldiers and to renew the war. He was so fortunate as to secure the services of a noble and valiant captain, of whom the free lances declared that they had never served under so brave a man: and whose name is recorded as Riccardo Imprennante degli Annibaldi—Richard the enterprising, perhaps—and the war was pursued with vigour under him. Within Rome things did not go quite so well. Rienzi had to explain his conduct in respect to Fra Moreale to his own councillors. "Sirs," he said, "do not be disturbed by the death of this man; he was the worst man in the world. He has robbed churches and towns; he has murdered both men and women; two thousand depraved women followed him about. He came to disturb our state, not to help it, meaning to make himself the lord of it. And this is why we have condemned that false man. His money, his horses, and his arms we shall take for our soldiers." We scarcely see the eloquence for which Rienzi was famed in these succinct and staccato sentences in which his biographer reports him; but this was our chronicler's own style, and they are at least vigorous and to the point.

"By these words the Romans were partly quieted," we are told, and the course of the history went on. The siege of Palestrina went well, and garrisons were placed in several of the surrounding towns, while Rienzi held the control of everything in his hands. Some of his troops withdrew from his service, probably because of Fra Moreale; but others came—archers in great numbers, and three hundred horsemen.

"He maintained his place at the Capitol in order to provide for everything. Many were the cares. He had to procure money to pay the soldiers. He restricted himself in every expense; every penny was for the army. Such a man was never seen; alone he bore the cares of all the Romans. He stood in the Capitol arranging that which the leaders in their places afterwards carried out. He gave the orders and settled everything, and it was done—the closing of the roads, the times of attack, the taking of men and spies. It was never ending. His officers were neither slow nor cold, but no one did much except the hero Riccardo, who night and day weakened the Colonnese. Stefanello and his Colonnas, and Palestrina consumed away. The war was coming to a good end."

To do all this, however, the money of Moreale was not enough. Rienzi had to impose a tax upon wine, and to raise that upon salt, which the citizens resented. Everything was for the soldiers. His own expenses were much restricted, and he seemed to expect that the citizens would follow his example. One of them, a certain Pandolfuccio di Guido, Rienzi seized and beheaded without any apparent reason. He was said to have desired to make himself lord over the people, the chronicler says. This arbitrary step seems to have caused great alarm. "The Romans were like sheep, and they were afraid of the Tribune as of a demon."

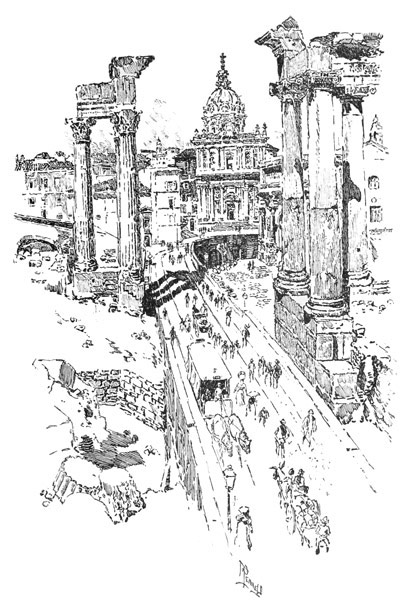

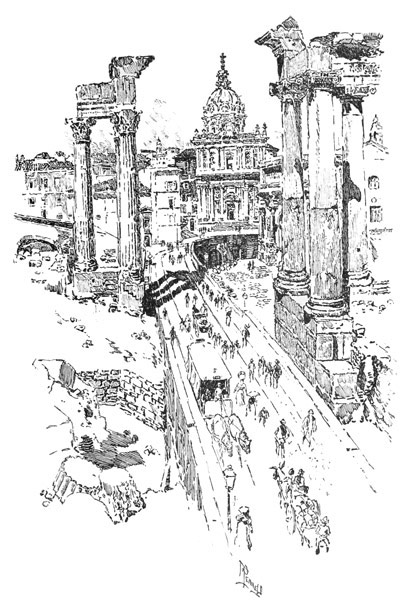

ANCIENT, MEDIÆVAL, AND MODERN ROME.

To face page 502.

By this time Rienzi once more began to show signs of that confusion of mind which we call losing the head—a confusion of irritation and changeableness, the resolution of to-day giving place to another to-morrow—and the giddiness of approaching downfall seized upon every faculty. As had happened on the former occasion, this dizziness of doom caught him when all was going well. He displaced his Captain, who was carrying on the siege of Palestrina with so much vigour and success, for no apparent reason, and appointed other leaders whose names even the biographer does not think it worth while to give. The National Guard—if we may so call them—fifty for each Rione—who were the sole guardians of Rome, were kept without pay, while every penny that could be squeezed from the people was sent to the army. These things raised each a new enemy to the Tribune, the Senator, once so beloved, who now for the second time, and more completely than before, had proved himself incapable of the task which he had taken upon him. It was on the 1st of August, 1354, that he had entered Rome with a rejoicing escort of all its cavalry and principal inhabitants—with waving flags and olive branches, and a throng that filled all the streets, the Popolo itself shouting and acclaiming—and had been led to the Piazza of the Ara Cœli, at the foot of the great stairs of the Capitol. On the last day of that month, a sinister and tragic assembly, gathered together by the sound of the great bell, thronged once more to the foot of these stairs, to see the great soldier, the robber knight, the terror of Italy, executed. And it was still only September, the Vita says—though other accounts throw the catastrophe a month later—when the last day of Rienzi himself came. We know nothing of the immediate causes of the rising, nor who were its leaders. But Rome was in so parlous a state, seething with so many volcanic elements, that it must have been impossible to predict from morning to morning what might happen. What did happen looks like a sudden outburst, spontaneous and unpremeditated; but no doubt, from various circumstances which followed, the Colonna had a hand in it, who ever since the day of San Lorenzo had been Cola's bitterest enemies. This is how his biographer tells the tale:

"It was the month of September, the eighth day. In the morning Cola di Rienzi lay in his bed, having washed his face with Greek wine (no doubt a reference to his supposed habits). Suddenly voices were heard shouting Viva lo Popolo! Viva lo Popolo! At this sound the people in the streets began to run here and there. The sound increased, the crowd grew. At the cross in the market they were joined by armed men who came from St. Angelo and the Ripa, and from the Colonna quarter and the Trevi. As they joined, their cry was changed into this, Death to the traitor, Cola di Rienzi, death! Among them appeared the youths who had been put in his lists for the conscription. They rushed towards the palace of the Capitol with an innumerable throng of men, women and children, throwing stones, making a great clamour, encircling the palace on every side before and behind, and shouting, 'Death to the traitor who has inflicted the taxes! Death to him!' Terrible was the fury of them. The Tribune made no defence against them. He did not sound the tocsin. He said to himself, 'They cry Viva lo Popolo, and so do we. We are here to exalt the people. I have written to my soldiers. My letter of confirmation has come from the Pope. All that is wanted is to publish it in the Council.' But when he saw at the last that the thing was turning badly he began to be alarmed, especially as he perceived that he was abandoned by every living soul of those who usually occupied the Capitol. Judges, notaries, guards—all had fled to save their own skin. Only three persons remained with him—one of whom was Locciolo Pelliciaro, his kinsman."

This was the terrible awaking of the doomed man—without preparation, without the sound of a bell, or any of the usual warnings, roused from his day-dream of idle thoughts, his Greek wine, the indulgences to which he had accustomed himself, in his vain self-confidence. He had no home on the heights of that Capitol to which he had returned with such triumph. If his son Lorenzo was dead or living we do not hear. His wife had entered one of the convents of the Poor Clares, when he was wandering in the Apennines, and was far from him. There is not a word of any one who loved him, unless it might chance to be the poor relation who stood by him, Locciolo, the furrier, perhaps kept about him to look after his robes of minever, the royal fur. The cry that now surged round the ill-secured and half-ruinous palace would seem to have been indistinguishable to him, even when the hoarse roar came so near, like the dashing of a horrible wave round the walls: Viva lo Popolo! that was one thing. With his belle parole he could have easily turned that to his advantage, shouting it too. What else was he there for but to glorify the people? But the terrible thunder of sound took another tone, a longer cry, requiring a deeper breath—Death to the traitor:—these are not words a man can long mistake. Something had to be done—he knew not what. In that equality of misery which makes a man acquainted with such strange bedfellows, the Senator turned to the three humble retainers who trembled round him, and asked their advice. "By my faith, the thing cannot go like this," he said. It would appear that some one advised him to face the crowd: for he dressed himself in his costume as a knight, took the banner of the people in his hand, and went out upon the balcony:

"He extended his hand, making a sign that all were to be silent, and that he was about to speak. Without doubt if they had listened to him he would have broken their will and changed their opinion. But the Romans would not listen; they were as swine; they threw stones and aimed arrows at him, and some ran with fire to set light to the door. So many were the arrows shot at him that he could not remain on the balcony. Then he took the Gonfalone and spread out the standard, and with both his hands pointed to the letters of gold, the arms of the citizens of Rome—almost as if he said 'You will not let me speak; but I am a citizen and a man of the people like you. I love you; and if you kill me, you will kill yourselves who are Romans.' But he could not continue in this position, for the people, without intellect, grew worse and worse. 'Death to the traitor,' they cried."

A great confusion was in the mind of the unfortunate Tribune. He could no longer keep his place in the balcony, and the rioters had set fire to the great door below, which began to burn. If he escaped into the room above, it was the prison of Bertram of Narbonne, the brother of Moreale, who would have killed him. In this dreadful strait Rienzi had himself let down by sheets knotted together into the court behind, encircled by the walls of the prison. Even here treachery pursued him, for Locciolo, his kinsman, ran out to the balcony, and with signs and cries informed the crowd that he had gone away behind, and was escaping by the other side. He it was, says the chronicler, who killed Rienzi; for he first aided him in his descent and then betrayed him. For one desperate moment of indecision the fallen Tribune held a last discussion with himself in the court of the prison. Should he still go forth in his knight's dress, armed and with his sword in his hand, and die there with dignity, "like a magnificent person," in the sight of all men? But life was still sweet. He threw off his surcoat, cut his beard and begrimed his face—then going into the porter's lodge, he found a peasant's coat which he put on, and seizing a covering from the bed, threw it over him, as if the pillage of the Palazzo had begun, and sallied forth. He struggled through the burning as best he could, and came through it untouched by the fire, speaking like a countryman, and crying "Up! Up! a glui, traditore! As he passed the last door one of the crowd accosted him roughly, and pushed back the article on his head, which would seem to have been a duvet, or heavy quilt: upon which the splendour of the bracelet he wore on his wrist became visible, and he was recognised. He was immediately seized, not with any violence at first, and taken down the great stair to the foot of the Lion, where the sentences were usually read. When he reached that spot, "a silence was made" (fo fatto uno silentio). "No man," says the chronicler, "showed any desire to touch him. He stood there for about an hour, his beard cut, his face black like a furnace-man, in a tunic of green silk, and yellow hose like a baron." In the silence, as he stood there, during that awful hour, he turned his head from side to side, "looking here and there." He does not seem to have made any attempt to speak, but bewildered in the collapse of his being, pitifully contemplated the horrible crowd, glaring at him, no man daring to strike the first blow. At last a follower of his own, one of the leaders of the mob, made a thrust with his sword—and immediately a dozen others followed. He died at the first stroke, his biographer tells us, and felt no pain. The whole dreadful scene passed in silence—"not a word was said," the piteous, eager head, looking here and there, fell, and all was over. And the roar of the dreadful crowd burst forth again.

The still more horrible details that follow need not be here given. The unfortunate had grown fat in the luxury of these latter days. Grasso era horriblimente. Bianco come latte ensanguinato, says the chronicler: and again he places before us, as at San Lorenzo seven years before, the white figure lying on the pavement, the red of the blood. It was dragged along the streets to the Colonna quarter; it was hung up to a balcony; finally the headless body, after all these dishonours, was taken to an open place before the Mausoleum of Augustus, and burned by the Jews. Why the Jews took this share of the carnival of blood we are not told. It had never been said that Rienzi was hard upon them; but no doubt at a period so penniless they must have had their full share of the taxes and payments exacted from all.

There is no moral even, to this tale, except the well-worn moral of the fickleness of the populace who acclaim a leader one moment, and kill him the next; but that is a commonplace and a worn-out one. If there were ever many men likely to sin in that way, it might be a lesson to the enthusiast thrusting an inexperienced hand into the web of fate, to confuse the threads with which the destiny of a country is wrought, without knowing either the pattern or the meaning of the weaving. He began with what we have every reason for believing to have been a noble and generous impulse to save his people. But his soul was not capable of that high emprise. He had the greatest and most immediate success ever given to a popular leader. The power to change, to mend, to make over again, to vindicate and to carry out his ideal was given him in the fullest measure. For a time it seemed that there was nothing in the world that Cola di Rienzi, the son of the wine-shop, the child of the people, might not do. But then he fell; the promise faded into dead ashes, the impulse which was inspiration breathed out and died away. Inspiration was all he had, neither knowledge nor the noble sense and understanding which might have been a substitute for it; and when the thin fire blazed up like the crackling of thorns under a pot, it blazed away again and left nothing behind. Had he perished at the end of his first reign, had he been slain at the foot of the Capitol, as Petrarch would have had him, his story would have been a perfect tragedy, and we might have been permitted to make a hero of the young patriot, standing alone, in an age to which patriotism was unknown. But the postscript of his second effort destroys the epic. It is all miserable self-seeking, all squalid, the story of any beggar on horseback, any vulgar adventurer. Yet the silent hour when he stood at the foot of the great stairs, the horrible mob silent before him, bridled by that mute and awful despair, incapable of striking the final blow, is one of the most intense moments of human tragedy. A large overgrown man, with blackened face and the rough remnants of a beard, half dressed, speechless, his head turning here and there—And yet no one dared to take that step, to thrust that eager sword, for nearly an hour. Perhaps it was only a minute, which would be less unaccountable, feeling like an hour to every looker on who was there and stood by.

No one in all the course of modern Roman history has so illustrated the streets and ways of Rome and set its excited throngs in evidence, and made the great bell sound in our very ears, a stuormo, and disclosed the noise of the rabble and the rule of the nobles, and the finery of the gallants, with so real and tangible an effect. The episode is a short one. The two periods of Rienzi's power put together scarcely amount to eight months; but there are few chapters in that history which is always so turbulent, yet lacks so much the charm of personal story and adventure, so picturesque and complete.

LETTER WRITER.