CHAPTER II.

CALIXTUS III.—PIUS II.—PAUL II.—SIXTUS IV.

It is not unusual even in the strictest of hereditary monarchies to find the policy of one ruler entirely contradicted and upset by his successor; and it is still more natural that such a thing should happen in a succession of men, unlike and unconnected with each other as were the Popes; but the difference was more than usually great between Nicolas and Calixtus III., the next occupant of the Holy See, elected 1455, died 1458, who was an old man and a Spaniard, and loved neither books nor pictures, nor any of the new arts which had bewitched (as many people believed) Pope Nicolas and seduced him into squandering the treasure of the Papacy upon unnecessary buildings, and still more unnecessary decorations. Calixtus was a Borgia, the first to introduce the horror of that name: but he was not in himself a harmful personage. "He spent little in building," says Platina, "for he lived but a short time, and saved all his money for the undertaking against the Turks," an enterprise which had become a very real and necessary one, now that Constantinople had fallen; but which had no longer the romance and sentiment of the Crusades to inspire it, though successive Pontiffs did their best to rouse Christendom on the subject. The aged Spanish Cardinal threw himself into it with all the fervour of his nature, which better than many others knew the mettle of the Moor. His short term of power was entirely occupied with this. A little building went on, which could not be helped: the walls had always to be looked to; but Pope Nicolas's army of scribes were all turned off summarily; the studios were closed, the artist people turned away about their business; all the great works put a stop to. Worse even than that—for Calixtus was a short-lived interruption, and perhaps might only have stopped the progress of events for some three years or so—Pope Nicolas's great plan, which was so complete, went out of sight, and was lost in the limbo of good intentions. His workmen were dispersed, and the fashion to which he had accustomed the world, changed. It was only resumed with earnestness after several generations, and never quite in the great lines which he had laid out. Neither did the new Pope get his Crusade, which might have been a better thing. Yet Calixtus was a person assai generoso, Platina tells us; in any case he occupied his great post for a very short time.

His successor, Pius II., 1458, on the other hand, was such a man as might well have inherited the highest purpose. He is almost better known as Eneas Silvius, a famous traveller and writer—not the usual peasant monk without a surname as so many had been, but one of the Piccolomini of Sienna, a great house, though ruined or partially ruined in his day. He was a man who had travelled much, and was known at all the courts; at one time young, heretical, adventurous, and ready to pull down all authorities, the life and soul of that famous Council of Bâle which took upon itself to depose Pope Eugenius; but not long after that outburst of independent youthfulness and energy was over, we find him filling the highest offices, the Legate of Eugenius and a very rising yet always much-opposed Cardinal. He it was who travelled to a remote and obscure little country called Scotland, in the Pope's name, to arrange matters there; and found the people very savage, digging stones out of the earth to make fires of them: but having plenty of fish and flesh, and surprisingly comfortable on the whole. He was one of the ablest men who ever sat on the Papal throne, but too reasonable, too moderate, too natural for the position. He loved literature, or at least he loved books, which is not always the same thing, and himself wrote a great many on various subjects; and he was so fortunate as to have the historian of the Popes, Platina—our guide, who we would have wished might live for ever—for his librarian, who was worth all the marble tombs in the world and all the epitaphs to a man whom he liked, and worse than any heathen conqueror to the man who was unkind to him.

Platina gives us a beautiful character of Pope Pius. He is very lenient to the faults of his youth, as indeed most historians are in respect to personages afterwards great, finding in their peccadilloes, we presume, a welcome and picturesque relief to the perfections that become a Pope. Yet Pius II. was never too perfect. He was a man who disliked the narrowness of a court, and loved the fresh air, and to give audience in his garden, and to eat his modest meal beside the tinkling of a fountain or under the shade of trees. He loved wit and a joke, and even gave ear to ridiculous things and to the excellent mimicry of a certain Florentine, who "took off" the courtiers and other absurd persons, and made his Holiness laugh. And he was hasty in temper, but bore no malice, and paid no attention to evil reports raised about himself. "He never punished those who spoke ill of him, saying that in a free city like Rome, every one should speak freely what he thought." He hated lying and story-tellers, and never made war unless he was forced to it. Whenever he was freed from the trials of business he took his pleasure in reading or in writing. "Books were more dear to him than sapphires or emeralds," says Platina, with a shrewd prick by the way at his successor, Paul, as we shall afterwards see, "and he was used to say that his chrysolites and other jewels were all enclosed in them." He never took a meal alone if he could help it, but loved a lively companion, and to make his little feasts in his garden as we have said, shocking much the scandalised courtiers, who declared that no other Pope had ever done such a thing; for which Pope Pius cared nothing at all. He wrote upon all kinds of subjects; from a grammar which he made for the little King of Hungary, to histories of various kingdoms, and philosophical disquisitions. Indeed the list of his subjects is like that of a series of popular lectures in our own day. "He wrote many books in dialogue—upon the power of the Council of Bâle, upon the sources of the Nile, upon hunting, upon Fate, upon the presence of God." If he had been a University Extension lecturer, he could scarcely have been more many-sided. And he wrote largely upon peace, no less than thirty-two orations "upon the peace of kings, the concord of princes, the tranquillity of nations, the defence of religion, and the quiet of the world." There was neither peace among kings, concord among princes, nor tranquillity among nations when Pope Pius delivered and collected his orations. They ought to have had all the greater effect; but we fear he was too wise a man to put much faith in any immediate result. His greatest work, however, was his Commentaries, an enlarged and philosophical study of his own times, which he did not live long enough to finish.

This Pontiff carried on the work of his predecessor more or less, but without any great zeal for it. "He collected manuscripts, but with discretion; he built, but it was in moderation," Bishop Creighton says. Platina, with more warmth, tells us that "he took great delight in building," but he seems to have confined himself to his own immediate surroundings, working at the improvement of St. Peter's, building a chapel, putting up a statue, restoring the great flight of stairs which then as now led up to the portico which previous Popes had adorned; and adding a little to the defences and decoration of the Vatican. He is suspected of having had a guilty liking for the Gothic style in architecture which greatly shocked the Roman dilettanti; and certainly expressed his admiration for some of the great churches in Germany with enthusiasm. One great piece of architectural work he did, but it was not at Rome. It was in the headquarters of his family at Sienna, and specially in the little adjacent town of Corsignano, where he was born, one of those little fortified villages which add so much to the beauty of Italy. This little place he made glorious with beautiful buildings, forgetting his native wisdom and discretion in the foolishness of that narrow but intense patriotism which bound the Italian to his native town, and made it the joy of the whole earth to his eyes. It gives a charm the more to his interesting character that he should have been capable of such a folly; though not perhaps that he should have changed its name to Pienza, a reflection of his own pontifical name.

With this, however, we have nothing to do, and not very much altogether with the great Piccolomini, though he is one of the most interesting and sympathetic figures which has ever sat upon the papal throne. His death was a strange and painful conclusion to a life full of work, full of admirable sense and intelligence without exaggeration or pretence. He followed the policy of his predecessors in desiring to institute a Crusade, one more strenuously called for perhaps than any which preceded it, since Constantinople had now fallen into the hands of the Turks, and Christendom was believed to be in danger. It is scarcely possible to imagine that his full and active life should have been much occupied by this endeavour: nor can we think that this great spectator and observer of human affairs was consumed with anxiety in respect to a danger about which the civilised world was so careless: but in the end of his life he seems to have taken it up with tragical earnestness, perhaps out of compunction for previous indifference. The impulse which once moved whole nations to take the cross had died out; and not even the sight of the beautiful metropolis of Eastern Christianity fallen into the hands of the infidel, and so splendid a Christian temple as St. Sophia turned into a mosque had power to rouse Europe. The King of Hungary was the only monarch who showed any real energy in the matter, feeling his own safety imperilled, and Venice, also for the same reason, was the only great city; and except in these quarters the remonstrances and entreaties of Pius had no success. In these circumstances the Pope called his court about him and announced to them the plan he had formed, a most unlikely plan for such a man, yet possible enough if there was any remorseful sense of carelessness in the past. The Duke of Burgundy had promised to go if another prince would join him. The Pope determined that in the absence of any other he himself would be that prince. Old as he was, and sick, and no warrior, and perhaps with but little of the zeal which makes such a self-devotion possible, he would himself go forth to repel the infidel. "We do not go to fight," he said, with faltering voice. "We will imitate those who, when Israel fought against Amalek, prayed on the mountain. We will stand on the prow of our ship or upon some hill, and with the holy Eucharist before our eyes, we will ask from our Lord victory for our soldiers." After a pause of alarm and astonishment the Cardinals consented, and such preparations as were possible were made. It was published throughout all Christendom that the Pope was to sail from Ancona at a certain date, and that every one who could provide for the expenses of the journey should meet him there. He invited the old Doge of Venice to join with himself and the Duke of Burgundy, also an old man. "We shall be three old men," he said, "and our trinity will be aided by the Trinity of Heaven." A kind of sublimity was in the suggestion, a sublimity almost trembling on the borders of the ridiculous; for the enterprise was no longer one which accorded with the spirit of the time, and all was hesitation and difficulty. A miscellaneous host crowded to Ancona, where the Pope, much suffering, was carried in his litter, quite unfit for a long journey; but the most of them had no money and had to be sent back; and the Venetian galleys engaged to transport those who were left did not arrive till the pilgrims had waited long, and were worn out with delay and confusion. They arrived at last a day or two before Pope Pius died, when he was no longer capable of moving—and with his death the ill-fated Crusade fell to pieces and was heard of no more. It was the most curious end, in an enthusiasm founded upon anxious calculation, of a man who was never an enthusiast, whose eyes were always too clear-sighted to permit him to be led away by feeling, a man of letters and of thought, rather than of romantic-solemn enterprises or the zeal of a martyr. That he was a kind of martyr to the strong conviction of a danger which threatened Christendom, and the forlorn hope of repelling it, there can be no doubt.

Pius II. was succeeded in 1464 by Paul II., also in his way a man of more than usual ability and note. He was a Venetian, the nephew of the last Venetian Pope, Eugenius; and it was he who built, to begin with, the fine palace still called the Palazzo Venezia, with which all visitors to Rome are so well acquainted. It was built for his own residence during his Cardinalate, and remained his favourite dwelling, a habitation still very much more in the centre of everything, as we say, than the remote and stately Vatican. The reader will easily recall the imposing appearance of this fine building, placed at the end of the straight street—the chief in Rome—in which were run the many races which formed part of the carnival festivities, a recent institution in Pope Paul's day. The street was called the Corso in consequence; and it is not long since the last of these races, one of horses without riders, was abolished. The Palazzo Venezia commanded the long straight street from its windows, and all the humours and wonders of the town, in which the Pope took pleasure. It was Paul's fate to make himself an implacable enemy in the often contemned, but—as regards the place in history of either pope or king—all-important class of writers, which it must have seemed ridiculous indeed for a Sovereign Pontiff to have kept terms with, on account of any power in their hands. But this was a shortsighted conclusion, unworthy the wisdom of a Pope. And the result of the Pontiff's ill-treatment of the historian Platina, to whom we are so much indebted, especially for the lives of those Popes who were his contemporaries, has been a lasting stigma upon his character, which the researches of the impartial critics of a later age have shown to be partly without foundation, but which until quite recently was accepted by everybody. In this way a writer has a power which is almost absolute. We have seen in our own days a conspicuous instance of this in the treatment by Mr. Froude of the life of Thomas Carlyle. Numbers of Carlyle's friends made instant protest against the view taken by his biographer; but they did so in evanescent methods—in periodical literature, the nature of which is to die after it has had its day—while a book remains. Very likely many of Pope Paul's friends protested against the coolly ferocious account of his life given by the aggrieved and revengeful author; but it is only quite recently, in the calm of great distance, that people have come to think—charitably in respect to Pope Paul II.—that perhaps Platina's strictures might not be true.

Platina, however, had great provocation. He was one of the disciples of the famous school of Humanists, the then new school of learning, literature, and criticism, which had arisen under the papacy and patronage of Pope Nicolas V., and had continued to exist, though with less encouragement, under his successors. Pius II. had not been their patron as Nicolas was, but he had not been hostile to them, and his tastes were all of a kind congenial to their work. But Paul looked coldly upon the group of contemptuous scholars who had made themselves into an academy, and vapoured much about classical examples and the superiority of ancient times. He had no quarrel with literature, but he persuaded himself to believe that the academy which talked and masqueraded under classic names, and played with dangerous theories of liberty, and criticism of public proceedings, was a nest of conspirators and heretics scheming against himself. There was no foundation whatever for his fears, but that mattered little in those arbitrary days. This is Platina's own account of the matter:

"When Pius was dead and Paul created in his place, he had no sooner grasped the keys of Peter, than he proceeded—whether in consequence of a promise to do so, or because the decrees and proceedings of Pius were odious to him—to dismiss all the officials elected by Pius, on the ground that they were useless and ignorant (as he said): and deprived them of their dignity and revenues without permitting them to say a word in their own defence, though they were men who for their erudition and doctrine had been gathered together from all the ends of the world, and attracted to the court of Rome by the promise of great reward. The College was full of men of letters and virtuous persons learned in the law both divine and human. Among them were poets and orators who gave no less ornament to the court than they received from it. Paul sent them all away as incapable and as strangers, and deprived them of everything, although those who had bought their offices were allowed to retain them. Those who suffered most attempted to dissuade him from this intention, and I, who was one of them, begged earnestly that our cause might be committed to the judge of the Rota. Then he fixed on me his angry eyes. 'So,' he said, 'thou wouldst appeal to other judges against the decision we have made! Know ye not that all justice and law are in the casket of our bosom? Thus I will it to be. Begone, all of you! for, whatever you may wish I am Pope, and according to my pleasure can make and unmake.'"

After hearing this determined assertion of right, the displaced scholars withdrew, but continued to plead their cause by urgent letters, which ended at last in an unwise threat to make the continental princes aware how they were treated, and to bring about the Pope's ears a Council, to which he would be obliged to give account. The word Council was to a Pope what the red flag is to a bull, and in a transport of rage Paul II. threw Platina into prison. He never in his life did a more foolish thing. The historian was kept in confinement for two years, and passed one long winter without fire, subjected to every hardship; but finally was set free by the intercession of Cardinal Gonzaga, and remained, by order of the Pope, under observation in Rome, where watching with a vigilant eye all that went on, he laid up his materials for that brief but scathing biography of Paul II. which forms one of the keenest effects in his work, and from which the Pope's memory has never recovered. It is a dangerous thing to provoke a man of letters who has a keen tongue and a gift of recollection, especially in those days when such men were not so many as now.

Nevertheless Platina did a certain justice to his persecutor. "He built magnificently," he says, "splendidly in St. Marco, and in the Vatican." The Church of St. Marco is close to the Palazzo Venezia where Paul chiefly lived; he had taken his title as Cardinal from his native saint. Both in St. Peter's and in the Vatican he carried on the works begun by his predecessors, and though he was unkind to the scholars, he was not so in every case. "He expended his money liberally enough," says Platina, "giving freely to poor Cardinals and bishops, and to princes and persons of noble houses when cast out of their homes, and especially to poor women and widows, and the sick who had no one else to think of them. And he also took great trouble to secure that corn and other things necessary to life should be furnished in abundance, and at lower prices than had been known ever before." These were good and noble qualities which his enemy did not attempt to disguise.

The special service done by Pope Paul to the city would seem, however, to have been the restoration of some of those ancient monuments which belonged to imperial Rome, of which none of his predecessors had made much account. If he still helped himself freely, like them, from the great reservoir of the Colosseum, he bestowed an attention and care, which they had not dreamed of, upon some of the great works of classic art, the arches of Titus and of Septimus Severus in particular, and the famous statue of Marcus Aurelius. M. Muntz comments with much spirit on the reason why this Pope's works of restoration have been so little celebrated. His taste was toward sculpture rather than painting. "To the eyes of the world," says the historian of the arts, "the smallest fresco is of more account than the finest monuments of architecture, or of sculpture. Nicolas V. did better for his fame in engaging Fra Angelico than in undertaking the reconstruction of St. Peter's. Pius II. owes a sort of posthumous celebrity to the paintings in the library of the cathedral of Sienna."

The same classical tastes of which he thus gave token made Pope Paul a great collector of bronzes, cameos, medals, intaglios, the smaller precious objects of ancient art; the love of which he was the first to bring back as a special study and pursuit. His collection of these was wonderful for his time, and great for any time. All the other adornments of ancient art were dear to him, and his palace, which, after all, is his most complete memorial in Rome, was adorned like a bride with every kind of glory in carved and inlaid work, in vessels of gold and silver, embroideries and tapestries. He had the still more personal and individual characteristic of a love for fine clothes, which the gorgeous costumes of the popedom permitted him to indulge in to a large extent: and jewels, which he not only wore like an Eastern prince, but kept about him unset in drawers and cabinets for his private delight, playing with them, as Platina tells us, in the silent hours of the night. Some part at least of these magnificent tastes arose no doubt from the fact that he was himself a magnificent specimen of manhood, so distinguished in personal appearance that he had the naïve vanity of suggesting the name of Formosus for himself when elected Pope, though he yielded the point to the scandalised remonstrances of the Cardinals. This simplicity of self-admiration, so undoubting as to be almost a moral quality, no doubt gave meaning to the glorious mitres and tiara encrusted with the richest jewels, which it gave him so much pleasure to wear, and which take rank with the other great embellishments of Rome, though their object was more personal than official. The habits of his life were strange, for he slept during the day, and performed the duties of life during the night, the reason assigned for this being that he was tormented by a cough which prevented him from sleeping at the usual hours. "It was difficult to come to speech of him," Platina says, for this reason. "And when, after long waiting, he opened the door, you were obliged rather to listen than to speak; for he was very copious and long in speaking. In everything he desired to be thought astute, and therefore his conversation was in very intricate and ambiguous language He liked many sorts of viands on his table, all of the worst taste; and took much pleasure in eating melons, crawfish, pastry, fish, and salt pork, from which, I believe, came the apoplexy from which he died." Thus the prejudices of his enemy penetrated the most private details of the Pope's life. The venom of hatred defeats itself and becomes ridiculous when carried so far.

His fine collection was seized by his successor and broken up, as is the fate of such treasures; and his works in St. Peter's, as we shall see, had much the same fate, along with the great works of his predecessor for the embellishment of the same building, all of which perished or were set aside in the fever of rebuilding which ensued. But there is still a sufficient memorial of him in the sombre magnificence of his Venetian palace, to recall to us the image of a true Renaissance Pope, mingling the most exquisite tastes with the rudest, the perfection of personal vanity—for he loved to see himself in a procession, head and shoulders over all the people—with the likings of a gondolier. Thus we see him in the records of his contemporaries, watching from his windows the strange sports in the long street newly named the Corso, races of men and of horses, and carnival processions accompanied by all the cumbrous and coarse humour of the period; or a stranger sight still, seated by night in his cabinet turning over his wealth of sparkling stones, enjoying the glow of light in them and twinkle of many colours, while the big candles flared, or a milder light shone from the beaks of the silver lamps. Notwithstanding which strange humours, tastes, and vanities, he remains in all these records a striking and remarkable figure, no intellectualist, but an effective and notable man.

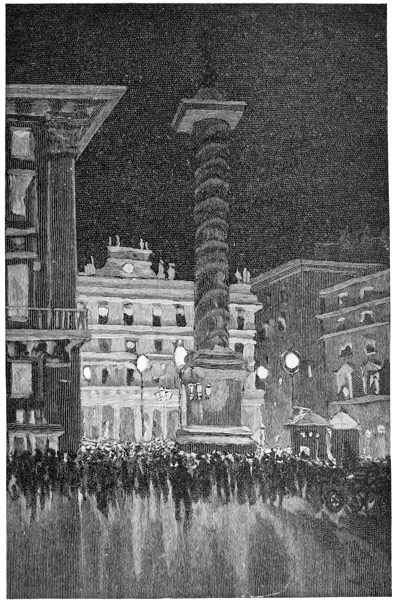

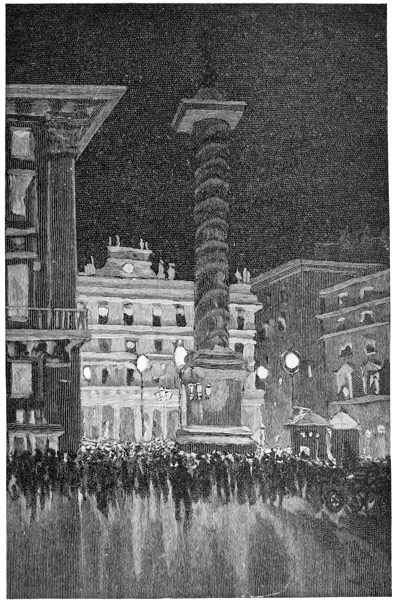

PIAZZA COLONNA,

To face page 564.

It is not the intention of these chapters to enter at all into the political life of the Popes of this period. They were still a power in Christendom, perhaps no less so that the Papacy had ceased to maintain those great pretensions of being the final arbiter in all disputes among the nations. But the papal negotiations, as always, came to very little when not aided by the events which are in no man's hand. Matthias of Hungary, though supported by all the influence and counsels of Pope Paul, made little head against the heretical George Podiebrad of Bohemia, until death suddenly overtook that prince, and left a troubled kingdom without a head, at the mercy of the invaders, an event such as constantly occurred to overturn all combinations and form the crises of history under a larger providence than that of human effort. And Paul no more than Pius could move Christendom against the Turk, or form again, when all its elements had crumbled, and the inspiration of enthusiasm was entirely gone, a new crusade. So far as our purpose goes, however, the Venetian Palace, the Church of St. Marco attached to it, and certain portions of the Vatican, better represent the life of this Pope, to whom the picturesque circumstances of his life and the rancour of a disappointed man of letters have given a special place of his own in the long line, than any summary we could give of the agitated sea of continental politics. The history of Rome was working up to that climax, odious, dazzling, and terrible, to which the age of the Renaissance, with all its luxury, its splendour, and its vice, brought the great city, and even the Church so irrevocably bound to it. Nicolas, Pius, and Paul at the beginning of that period, yet but little affected by its worst features, give us a pause of satisfaction before we get further. They were very different men. Pope Nicolas, with his crowd of copyists forming a ragged regiment after him, and the noise of all the workshops in his ears; and Paul, alone in his chamber pouring from one hand to another the stream of glowing and sparkling jewels which threw out radiance like the waterways of his own Venice under the light, afford images as unlike as it is possible to conceive; while the wise and thoughtful Pius, with those eyes "which had kept watch o'er man's mortality," stands over both, the perennial spectator and commentator of the world. They were all of one mind to glorify Rome, to make her a wonder in the whole earth, as Jerusalem had been, if not to pave her streets with gold, yet to line them with noble edifices more costly than gold, and to build and adorn the first of Christian churches, the shrine to which every Christian came. Alas! by that time it was beginning to be visible that all Christians would not long continue to come to the one shrine, that the pictorial age of symbols and representations was dying away, and that Rome had not learned at all how to meet that great revolution. It was not likely to be met by even the most splendid restoration of the fated city, any more than the necessities of the people were to be met by those other resurrections of institutions dead and gone, attempted by Rienzi, and his still less successful copyist Porcaro; but how were these men to know? They did their best, the worst of them not without some noble meaning, at least at the beginning of their several careers; but they are all reduced to their place, so much less important than they believed, by the large sweep of history, and the guidance of a higher hand.

Paul II. died in August 1471. Another order of man now succeeded these remarkable personages, the first of the line of purely secular princes, men of the world, splendid, unprincipled, and more or less vicious, although in this case it is once more a peasant, without so much as a surname, Sixtus IV., who takes his place in the scene, and who has left his name more conspicuously than any of his predecessors upon the later records of Rome. So far as the reader is concerned, the inscription at the end of the life of Pope Paul is a more melancholy one than anything that concerns that Pope. "Fin qui, scrisse il Platina," says the legend. We miss in the after-records his individual touch, the hand of the contemporary, in which the frankness of the chronicler is modified by the experience and knowledge of an educated mind. The work of Panvinio, scriba del Senato e popolo Romano, who completes the record, is without the same charm.

We have said that Pope Sixtus IV. was a man without a surname, Francesco of Savona, his native place furnishing his only patronymic: but there was soon found for him—probably for the satisfaction of the nephews who took so large a place in his life—a name which bore some credit, that of a family of gentry in which it is said the young monk had fulfilled the duties of tutor in the beginning of his career. By what imaginary pedigree this was brought about we are not told; but it is unlikely that the real della Roveres would reject the engrafting of a great Pope into their stock, and it soon became a name to conjure with throughout Italy. Although he also vaguely made proposals about a Crusade, and languidly desired to drive back the Turk, he was a man much more interested in the internal squabbles of Italy, and in his plans for endowing and establishing his nephews, than in any larger purpose. But he was also a man of boundless energy and power, cooped up for the greater part of his life, but now bursting forth like the strong current of a river. Whether it was from a natural inclination towards beauty and splendour, or because he saw it to be the best way in which to distinguish himself and make his own name as well as that of his city glorious, matters little to the result. He was, in the fullest sense of the words, one of the chiefest of the Popes who made the modern city of Rome, as still existing and glorious in the sight of all the world.

It was still a confused and disorderly place, in which narrow streets and tortuous ways, full of irregularities and projections of all kinds, threaded through the large and pathetic desert of the ancient city, leaving a rim of ruin round the too-closely clustered centre of life where men crowded together for security and warmth after the custom of the mediæval age—when Sixtus began to reign; and this it was which specially impressed King Ferdinand of Naples when he paid his visit to the Pope in the year 1475, and had to be led about by Cardinals and other high officials, sometimes, it would appear, by his Holiness himself, to see the sights. The remarks he made upon the town were very useful if not quite civil to the seat of Roman influence and authority. Infessura gives this little incident vividly, so that we almost see the streets with t