III

FULL MOON TO OLD MOON

AFTER dinner, in the brilliantly lighted drawing-room, we once more spread out the photographs on a table.

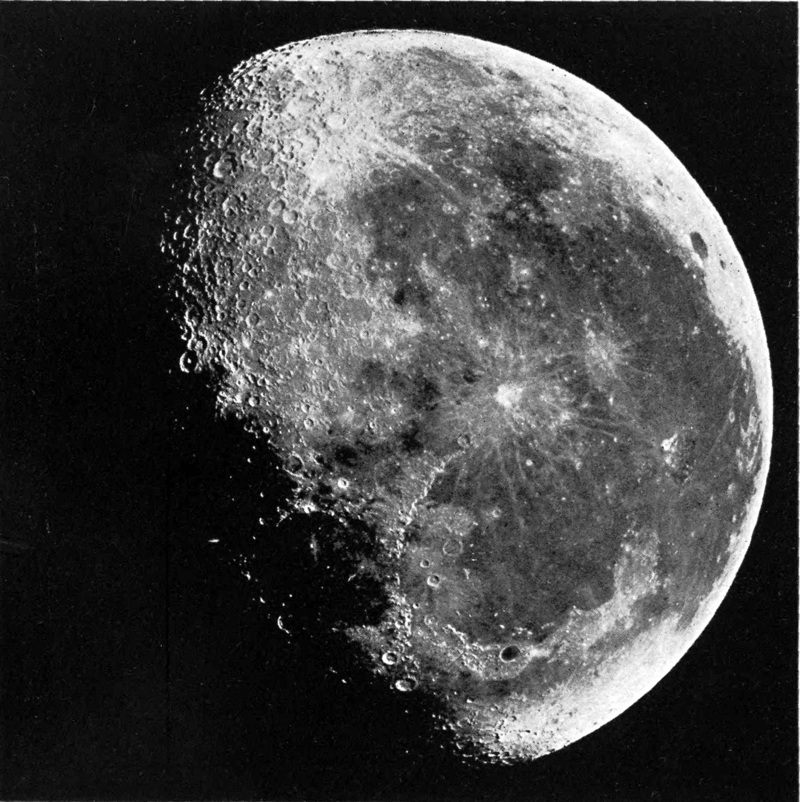

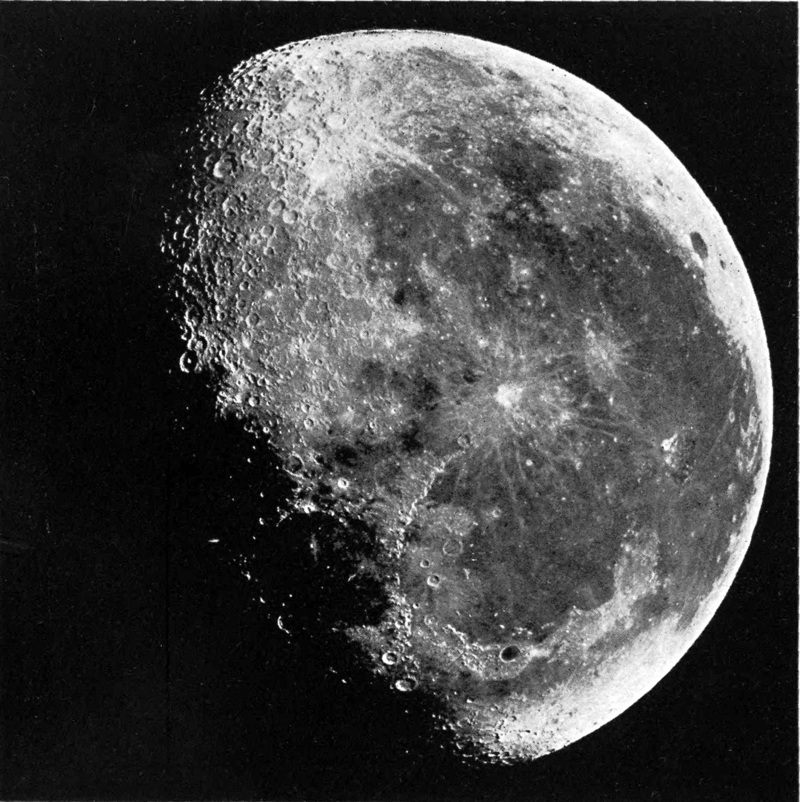

“This time,” I said, taking up No. 14, “we are going to watch the advance of night over the moon. Before, it was the march of sunrise that we followed. Both begin at the same place, the western edge or limb of the moon. Comparing this photograph, which was taken when the moon was about fifteen and two-third days old, with No. 13, taken when the moon’s age was more than a day less, you perceive, at a glance, wherein the chief difference lies. In No. 13 sunrise is just reaching the eastern limb; in No. 14 sunset has begun at the western limb. Having watched day sweep across the lunar world, we shall now see night following on its track. West of the Mare Crisium and the Mare Fœcunditatis, which I expect you to recognize on sight by this time, darkness has already fallen, and the edge of the moon in that direction is invisible. The long, cold night of a fortnight’s duration has begun its reign there. The setting sun illuminates the western wall of the ring mountain Langrenus, which you will remember was one of the first notable formations of the kind that we saw emerging in the lunar morning. But then it was its eastern wall that was most conspicuous in the increasing sunlight. For the selenographer the difference of aspect presented by the various objects of the lunar world when seen first under morning and then under evening illumination is extremely interesting and important. Many details not readily seen, or not visible at all, in the one case become conspicuous in the other. But it is only close along the line where night is advancing that notable changes are to be seen. Over the general surface of the moon there is not yet any perceptible change, because the sunshine still falls nearly vertical upon it. Tycho’s rays are as conspicuous as ever. Aristarchus, away over on the eastern side, is, if possible, brighter than before, and the three small dark ovals, Endymion a little west of the north (or lower) point, Plato at the edge of the Mare Imbrium, and Grimaldi near the bright eastern limb, are all conspicuous.”

NO. 14. AUGUST 26, 1904; MOON’S AGE 15.65 DAYS.

“But look!” exclaimed my friend, putting her finger upon the photograph. “Here is something that you have not mentioned at all. I believe that I have made a discovery, although you probably will not accept it as a scientific one. I see here a dark woman in the moon.”

“I confess,” I replied, “that I am not acquainted with her, and do not even see her. Please point her out to me.”

“She appears in profile, like the brilliant Moon Maiden, but is not so much of a beauty. In fact I begin to suspect that she is the ‘Old Woman in the Moon,’ that I have often heard of.”

“Positively I do not see her.”

“Then I will try to recall some of the names that you have been telling me in order to indicate where you should. She faces west and occupies most of the eastern half of the disk. Her head is under Tycho, toward the northeast, I suppose you would say. The bright double ray that you pointed out in one of the preceding pictures lies across the top of her head and over her ear. Her face seems to be formed by a part of the Mare Nubium—you observe how well I have learned your selenographical terms—and her hooked nose is composed of a kind of bay, projecting into the bright part below Tycho. Her front hair is banged, and the Mare Humorum constitutes her chignon. She has a short neck, and a humped back, consisting of the Oceanus Procellarum. Copernicus resembles a starry badge that she wears on her breast, and Aristarchus glitters on the inner side of the elbow of her long arm. The Mare Imbrium seems to be a sort of round, bulky object that she carries on her knee, and she appears to be gazing with intentness in the direction of the Mare Tranquillitatis.”

“Ah, yes,” I said, laughing, “I see her plainly enough now. I really cannot say that your discovery is likely to be recorded in astronomical annals, but nevertheless I congratulate you upon having made it, if only for the reason that henceforth you can never forget the names and locations of the lunar ‘seas’ and other objects that you have been compelled to remember in pointing out your ‘dark woman.’ In truth, her features are almost as well marked as those of the Moon Maiden, but you will hardly be able to find her again, except in a photograph, or with the aid of a telescope, because you must recollect that this picture shows the moon reversed top for bottom as compared with her appearance to the naked eye, or with an opera glass. But please look again at the objects along the western edge, for we are about to turn our attention to photograph No. 15 in which this will be no longer visible. You must say ‘good-by,’ or rather ‘good night,’ to the Mare Crisium and the Mare Fœcunditatis; for you will see them no more, until another lunar day has dawned.”

We next picked up photograph No. 15.

NO. 15. AUGUST 28, 1904; MOON’S AGE 17.41 DAYS.

“Here the age of the moon has increased to nearly seventeen and a half days. The sunset line has advanced to the borders of the Mare Nectaris and the Mare Tranquillitatis. Toward the south a vast region which was very brilliant in the morning and midday light with the reflections from mountain slopes and the rays of Tycho, has passed under the curtain of night. The great crater rings on the eastern border of the Mare Nectaris, and thence upward to the South Pole, are beginning to reappear, but with the shadows of their walls thrown in a direction opposite to that which they assumed before. By a little close inspection you will recognize Theophilus and its neighbors which were so conspicuous for many days while the sunrise was advancing, but which have been almost concealed in the universal glare of the perpendicular sunshine since the Full Moon phase was approached. On the Mare Tranquillitatis and the Mare Serenitatis it is late afternoon, and your favorite ‘Marsh of a Dream’ has become a true dreamland.”

“This oncoming of night,” said my friend, “seems to me more imposing, and more suggestive of mystery than was the advance of day.”

“Surely it is. Do we not experience similar sensations when night silently creeps over the earth? But it imparts a feeling of loneliness and desolation when we watch it swallowing up the barren mountains and plains of the lunar world that we do not experience in terrestrial life. There are no cheerful interiors on the moon to which one can retreat when darkness hides the landscapes. There is another thing about the lunar night to which I have made but scant reference thus far. I mean it’s more than Arctic chill. Imagine yourself standing there in the midst of the broad plain of the Mare Tranquillitatis. Toward the east you would see the sun close to the horizon, yet blazing bright and hot, without clouds or mists to temper its rays. The rocks or soil beneath your feet would perhaps be cold to the touch, because the surface of the moon radiates away the heat very quickly, but your face and hands would be almost scorched by the intense solar beams. Looking toward the west you would see the shining tips of mountains suddenly extinguished, one after another, and when the sharply defined edge of the advancing night passed over you it would be as if you had plunged into a cold bath. In a little while, if you remained motionless, you would be frozen. No clothing would suffice to keep you warm. Nothing that polar explorers have ever experienced can be likened to the cold of the lunar night. Only the apparatus of the laboratories for producing temperatures, capable, when combined with pressure, of liquifying and solidifying the air itself, can bring about upon the earth a lowering of temperature comparable with that which occurs during the lunar night.”

“But I do not exactly see why night should be so much colder on the moon than on the earth. She is not farther from the sun.”

“No, her average distance from the sun is the same as that of the earth. The reason why her nights are so cold is to be found in the absence of an atmosphere like ours. The air is the earth’s blanket, which serves a double purpose, tempering the heat by day with its vapors and winds, and keeping the earth warm at night by preventing the rapid radiation into space of the heat accumulated during the daylight hours. If there is any atmosphere at all upon the moon—and I shall tell you by and by what has been learned on that subject—it is so rare as compared with ours that it can exercise very little effect upon the temperature of the lunar surface.

“Now, look at the great range of the lunar Apennines. You will see that the eastern faces of these mountains are in the sunlight, and they cast no shadows, as they did in the lunar morning, over the Mare Imbrium. The same is true of the lunar Caucasus, and the lunar Alps. All of these mountains are very steep on the side facing the plains, and that is the side presented sunward in the lunar afternoon. By turning to photograph No. 16, we shall see this phenomenon more clearly displayed. This photograph, measured by the age of the moon when it was taken, is more than a day older than the other, but once again the effect of libration has, in part, counteracted for us the advance of the line of sunset. Still it has distinctly advanced. You will observe that it has now passed completely across the Mare Nectaris, and more than half across the Mare Tranquillitatis, while only the mountain tops along the western edge of the Mare Serenitatis remain to indicate its outlines in that direction. Theophilus, Cyrillus, and Catharina, on the eastern border of the Mare Nectaris, have again become very conspicuous, but this time in evening instead of morning light. See how sharply the western wall of Theophilus stands out against the darkness of night behind it, and how its central peak glows in the setting sun while all the vast hollow beneath it is black. The floors of Cyrillus and Catharina, being less profoundly sunken, are still illuminated. Below the Mare Serenitatis, the twin rings, Aristoteles and Eudoxus, are very conspicuous, and they show the same change of illumination as Theophilus, their western sides being strongly illuminated on their inner faces, while the eastern walls cast shadows into the interior. The mountainous character of the surface in the neighborhood of the North Pole of the moon seems to be more clearly brought out in evening than in morning light. In this picture the North Polar Region seems to be almost as much broken up with gigantic rings as is that surrounding the South Pole. In both cases, you observe, many of the rings are poised just on the edge of the lunar disk, and their libration alternately swings them in or out of view.”

NO. 16. AUGUST 29, 1904; MOON’S AGE 18.62 DAYS.

“Then the other side of the moon may not be very different from the side that is turned toward us.”

“In its general features I doubt if it is at all different. There was once a theory, which had considerable vogue, that the side of the moon turned away from the earth presented a great contrast with its earthward side. A German mathematician, Hansen, drew conclusions, which are no longer accepted, as to the form of the moon. He thought that the moon was elongated in the direction of the earth, somewhat like an egg, her center of figure being about thirty miles nearer to us than her center of gravity. This, if true, would make the part of the lunar surface that we see lie at a great elevation as compared with the other part, and the center of gravity being toward the other side would cause the atmosphere and water to gravitate in that direction.”

“What a pity that so interesting a theory should have been abandoned!”

“If interest were the only test of the value of a scientific theory knowledge would not advance very fast. Notice how this very photograph before us vindicates the true scientific attitude toward nature. It records all the facts within its range, and leaves the theories to us. The features of your ‘dark woman’ are, in their way, as clearly marked in the photograph as is the range of the lunar Apennines. It is for us to recognize the essential difference between the interpretations which we choose to put upon these two phenomena. Giving play to fancy, we see the figure of an old woman in the one case, and employing our reason we find a chain of unmistakable mountains in the other.”

“But surely you do not mean to aver that science has no other business than that of recording facts.”

“By no means. It is also the business of science to find hypotheses and to build up theories that will explain its facts and connect them together systematically, according to some underlying law. But as I have just intimated it is the mark of true science that it never retains a theory merely because it is interesting. The truth is the only touchstone. Still, even the most conscientious scientific investigator may be misled by his imagination. His greatest virtue is that he never lets his fancies deceive him after he has recognized their false character. Point out your ‘dark woman’ to the child, or the savage, and it will be in vain afterward to explain that her profile is made up of plains and mountains. The child and the savage are not scientific but imaginative, and only after a long education will they abandon the apparent for the real.

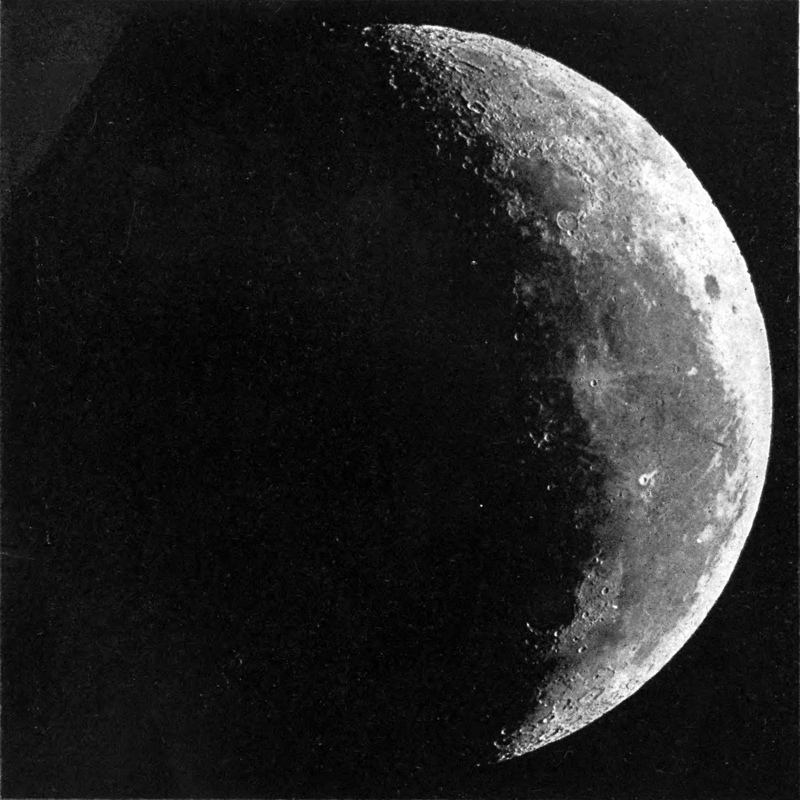

“I will ask you now to take up photograph No. 17. The age of the moon here is twenty days. Comparing it with the last photograph we see that Theophilus has disappeared, although Cyrillus and Catharina, being a little farther east, are yet visible. Half of the Mare Serenitatis is buried in night, and only a little of the eastern edge of the Mare Tranquillitatis remains visible. Aristoteles and Eudoxus are now very close to the terminator, and the shadows of their eastern walls are spreading farther over their floors. Aristarchus is very brilliant, as it is still early afternoon on that part of the moon, and the sunshine is intense. Observe that Kepler, the crater ring directly east of Copernicus, has become more conspicuous than we have seen it in any preceding photograph. This is especially true of the system of bright rays surrounding it, and it is due to the change of illumination. In the southern part of the moon, west of Tycho, you will now recognize many gigantic formations which we first saw when the sun was rising over them. Some of them are even more prominent in the sunset light. Among these is our old acquaintance Maurolycus, whose western wall is so brilliant that it resembles a tiny crescent moon. The double row of broad, dish-shaped walled plains along the central meridian has also become visible once more. In fact the amount of delicate detail and the sharpness of the definition in these photographs are very remarkable. Observe the curious mottling of the ‘seas.’ It is in some of the differences of tint, which correspond in telescopic views of the moon more or less closely with the varying shades in the photographs, that some selenographers have thought they could detect evidences of the presence of vegetation on the moon. We shall talk about that more in detail another time. It is sufficient just now to notice that the beds of the mares are by no means uniform either in tint or in level. All of them are more or less ‘rolling,’ like many of our prairies, and often winding chains of hills and huge cracklike ravines are visible in them. In this photograph the amount of detail shown in the Mare Imbrium is particularly striking. Notice how some of the crinkled rays from Copernicus extend almost to the center of the ‘sea,’ and how in front of the precipitous base of the Apennine range the lighter-colored ground, with three prominent ring plains in it, presents the appearance of shallows. Lying off the shore south of Plato and the Alps a number of isolated mountain peaks are seen, mere white specks on the gray background. The undulating character of the ‘bottom’ of the ‘Bay of Rainbows’ is also distinctly indicated. By the way, I should perhaps mention the names of the three rings lying off the front of the Apennines, for although they are among the most interesting on the moon they have hitherto escaped our special attention. The largest of the three is Archimedes, the second in size is Aristillus, and the smallest is Autolycus. You will hear of them again when we come to the large photograph of the Mare Imbrium and the Mare Serenitatis.

NO. 17. OCTOBER 10, 1903; MOON’S AGE 20.06 DAYS.

“Let me now prepare you for an almost dramatic change in the appearance of some of the most conspicuous lunar features which will take place when we pass from this photograph to No. 18. Direct your attention particularly to the chain of the Apennines. In No. 17 it lies very brilliant in the sunlight, with its western slopes distinctly visible, rising gradually from the shores of the Mare Serenitatis and the Mare Vaporum, while the ‘sea’ along its eastern front is bright with day. In No. 18 the Apennines have become simply a chain of illuminated mountain tips with comparative darkness all around them. Their western slopes are practically invisible, the Mare Imbrium on the east has turned dark, as if twilight had fallen over it—although as I have told you there is no twilight on the moon—and at its northern end the great range, with only its summits illuminated, projects like a row of electric lights far into the black night that has covered the plains beneath.

“Yet, although the Mare Imbrium has turned so dark as to be barely visible over its western half, the sun has by no means set upon it, and the darkness is perhaps greater than it should, theoretically, be under the circumstances. This phenomenon of the rapid darkening of the great lunar levels as the sun declines is one of the arguments that have been found to favor the hypothesis of the existence of vegetation. If, for the sake of discussion, we admit the possibility of vegetation growing on the lunar plains, it will be interesting once more to compare photographs Nos. 17 and 18.”

“Don’t say that it is merely for the sake of a discussion,” interrupted my friend. “I shall be far more deeply interested if you will simply say that it may be true.”

NO. 18. SEPTEMBER 29, 1904; MOON’S AGE 20.50 DAYS.

“Very well, let us put it that way, then. As I was remarking, if we again compare the two photographs, keeping the vegetation hypothesis in view, we may ascribe at least a part of the rapid darkening of the plain of the Mare Imbrium to a change in the color of the—what shall I say, grass?—covering it.”

“Good! good!” exclaimed my friend, clapping her hands. “Just listen to him! After gravely rebuking me so many times for my unscientific faith in the lunar inhabitants of a long past age, now you are talking of ‘grass’ on the moon.”

“You are hardly fair,” I protested. “It is you who have just led me to make an admission which many astronomers would laugh at, and you ought to support me with all the brilliance of your imagination when I try to picture a state of things so consistent with your predilections about the moon.”

“Oh, I do support you with all my heart!” she replied. “Pray go on, and tell me about the lunar grass.”

“Not just at present,” I said. “We are going to take that subject up again, and I may then succeed in convincing you that there is far more evidence for believing that vegetation exists on the moon in the present day than for believing that intellectual beings inhabited it at some unknown former period. I should warn you, too, that I have been using the contrasts of light and darkness between these two successive photographs simply as an illustration of what occurs in visual telescopic views; but that, for some reason, the lunar plains nearly always appear darker in photographs when contrasted with the mountainous regions than they do when viewed with the eye. Owing, also, to a variety of influences two successive photographs of the moon may differ in tone when the eye would detect no corresponding difference. All this, however, does not invalidate what I have said about the lunar ‘seas,’ or plains, darkening near sunset more rapidly than we should expect them to do, as a simple result of the low angle at which the sunlight strikes them.

“You will notice that the waning of day between photographs Nos. 17 and 18 has produced a remarkable change in the appearance of Tycho. Since the Full Moon phase Tycho has resembled a button rather than a volcanic crater, but now it has once more assumed the form of a very beautiful ring with its central peak clearly shown, its western wall, bright and its eastern wall casting a broad, black shadow. Most of the rays have now disappeared, only two or three, running over the eastern hemisphere, remaining visible. The immense walled plains near Tycho have again become prominent, Maginus toward the southwest, Clavius toward the south, and Longomontanus toward the southeast being the most conspicuous. Clavius is always a wonderful object for the telescope, but it is rather more interesting in the lunar morning than in the evening. Away over near the eastern limb, where the sun is still high, Grimaldi shows its dark oval, with a couple of mountain peaks on its western rampart shining brilliantly. The small, dark spot below it, toward the east, is in the walled plain, Riccioli. The bright spot with starlike rays, a long way south of Grimaldi, and east of the Mare Humorum, is Byrgius, a walled plain near which exists a small system of bright streaks resembling those surrounding Copernicus and Kepler, but much less extensive.”

“Do you recall my expression of impatience this morning when you were giving me the names of a long string of crater rings?” said my friend, smiling. “Well, I am now going to make a confession. Perhaps it is slightly of a penitential nature. I find now that these names, although they certainly are far from picturesque in most cases, begin to interest me, because, I suppose, I understand better the character and meaning of the things that they represent. The ceaseless Latin terminations no longer annoy me, for I do not think of them, but of the things themselves.”

“It is always so,” I replied, “whenever one takes up a new study. I know that you have dipped a little into botany, and I am sure that the Latin names which abound in that science must have repelled you at first. But after a time, when you had begun to recognize the beautiful flowers and the remarkable plants for which they stood, you found that even these names assumed a new character and became interesting and memorable. You will find it the same if you continue to study the moon. The most stupid designations will derive interest from their applications.”

“Yes, that is no doubt true. Still, I wish that Riccioli had possessed a little more imagination.”

“Be thankful, then, that he did not name the lunar ‘seas’ and ‘bays.’ You must now bid good night to your ‘dark woman.’ You observe that the Mare Nubium is beginning to fall under the shadow, and that her features are growing indistinct. If you will turn the photograph upside down you will find that the Moon Maiden has retired. She belongs exclusively to the western hemisphere, and it is only the eastern hemisphere of the moon that now remains visible to us, for we are close to the phase of Last Quarter. This is an aspect of the moon with which you may not be very familiar. To see the moon at Last Quarter, and particularly after she has passed that phase, we must rise near midnight and devote the early morning hours to observation. During these later phases, however, one may see the moon in the heavens during the daytime all through the forenoon and a part of the afternoon. She is a very beautiful object then, although few persons, I fear, ever take the trouble to look at her. The lighter parts of her surface assume a silvery tint in the daylight, and the dark plains seem suffused with a delicate blue from the surrounding sky. Exquisite views of the moon may then be obtained with a telescope. The glare of reflected light from the mountains and crater rings, which dazzles the eye at night, is so reduced that the telescopic image becomes beautiful, soft, and pleasing. The same principle has been very successfully applied in recent years to the study of the planet Venus. Her atmosphere is so abundant, in contrast to what we find on the moon, that she is as blinding in a telescope as a ball of snow glittering in full sunshine; but when seen in the daytime, her features, indistinct at the best, may be more clearly discerned.”

“Oh, you interest me deeply! If Venus is supplied with such an abundance of air, I suppose she is inhabited?”

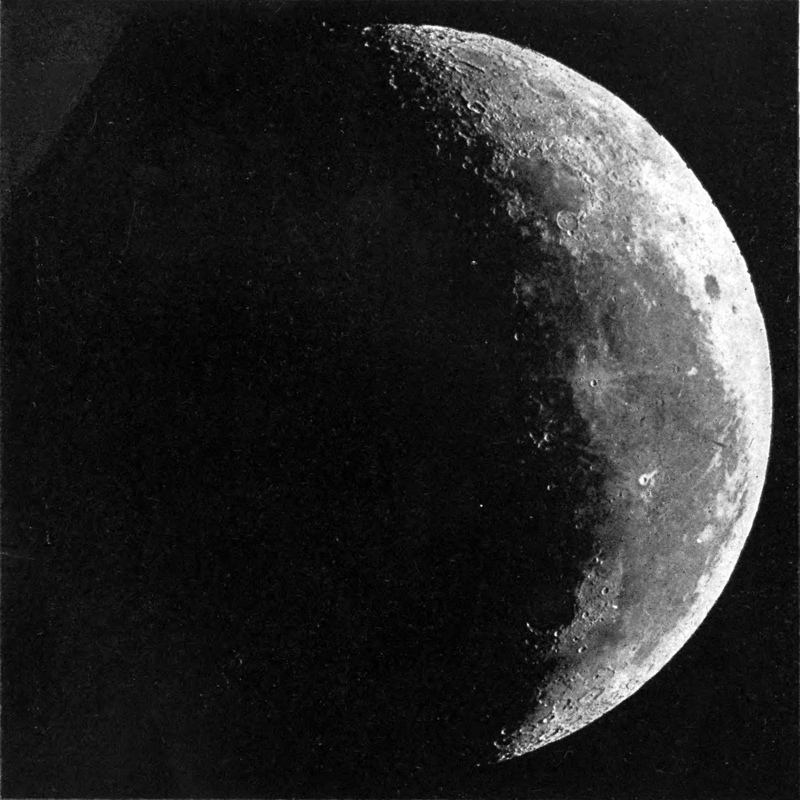

“It is not exactly orthodox among those calling themselves astronomers to talk of inhabitants on the planets, but I do not mind telling you privately that I think that Venus is most likely a world filled with all kinds of animate existences. Our present business, however, is with the moon, and I must recall your attention to the photographs. We shall next take up No. 19. Here the crescent shape becomes again evident, but reversed in position as compared with the crescent of the new and waxing moon. Only two of the ‘seas’ now remain completely in view—the Mare Humorum and the Oceanus Procellarum.”

“That term I think you have translated as the ‘Ocean of Tempests.’ Pray, do you know any reason why it should have been thus named?”

NO. 19. AUGUST 16, 1903; MOON’S AGE 23.81 DAYS.

“There is not the slightest reason that I know of. You must ascribe it to the vivid imagination of that old astronomer whom you so greatly admire. I regret, sometimes, that he cannot be here to explain to you the thoughts that occupied his mind. They must surely have been very captivating, even though not very scientific. Remark that there are many of the features of the eastern part of the moon which we can now discern more clearly than in any of the preceding pictures. Beginning at the top we see the vast inclosure of Longomontanus with the top of its encircling walls illuminated, while the interior is all in deep shadow. Its western rampart projects into the night and seems detached from the main body of the moon. Along the terminator below Longomontanus, what appears to be another immense walled plain presents a similar aspect. This, however, consists of several smaller formations grouped near together, only their loftiest points being illuminated. The steep borders of the Mare Humorum are finely shown. Notice how the floor of that little ‘sea,’ which is about the size of England, as Mr. Elger has remarked, is mottled with whitish spots, and how distinct the ring of Gassendi appears at the northern end of the mare. You can even see the comparatively small crater that crowns the northern wall of the ring. Southeast of the Mare Humorum are visible the great flat plains of Schiller and Schickard. Notice also how all the surface of the moon in that direction is freckled with crater pits, which resemble the impressions made by raindrops in soft sand. But the smallest of these pits is larger than the greatest volcanic crater on the earth.

“The Oceanus Procellarum is beautifully illuminated in this picture. In several places, particularly north of the Mare Humorum, parts of submerged rings are visible. These are great curiosities, and we shall see more of them elsewhere. Some selenographers believe that they are the remains of an earlier world in the moon, which was buried by a tremendous upheaval and outrush of molten material from the interior. You will remember, perhaps, that I spoke of a catastrophe of that kind when pointing out the half-buried ring of Fracastorius at the southern end of the Mare Nectaris.”

“Did that catastrophe occur after the formation of the huge lunar volcanoes?”

“It is difficult to say just when it occurred, but the appearances generally favor the view that it was subsequent to the great volcanic age. It is the opinion of Mr. Elger, whom I have once or twice mentioned as an English observer who has devoted special attention to the study of the moon’s surface, that the mares, as we now see them, do not represent the original beds of the lunar oceans. These beds, which, according to this view, were at first deeper, have been covered up, at least over a great part of their areas, by the outrush of molten lava. If they were ever filled with water it was very likely prior to that occurrence. But you must remember that all this is spec