IV

GREAT SCENES ON THE MOON

MY friend did not leave me in doubt on the following morning as to the genuineness of her interest in her new studies. The shadows of the trees in the park were yet as long drawn out as the silhouettes of lunar peaks at sunrise, when we resumed our place under the elm, and, at her request, I opened once more my portfolio.

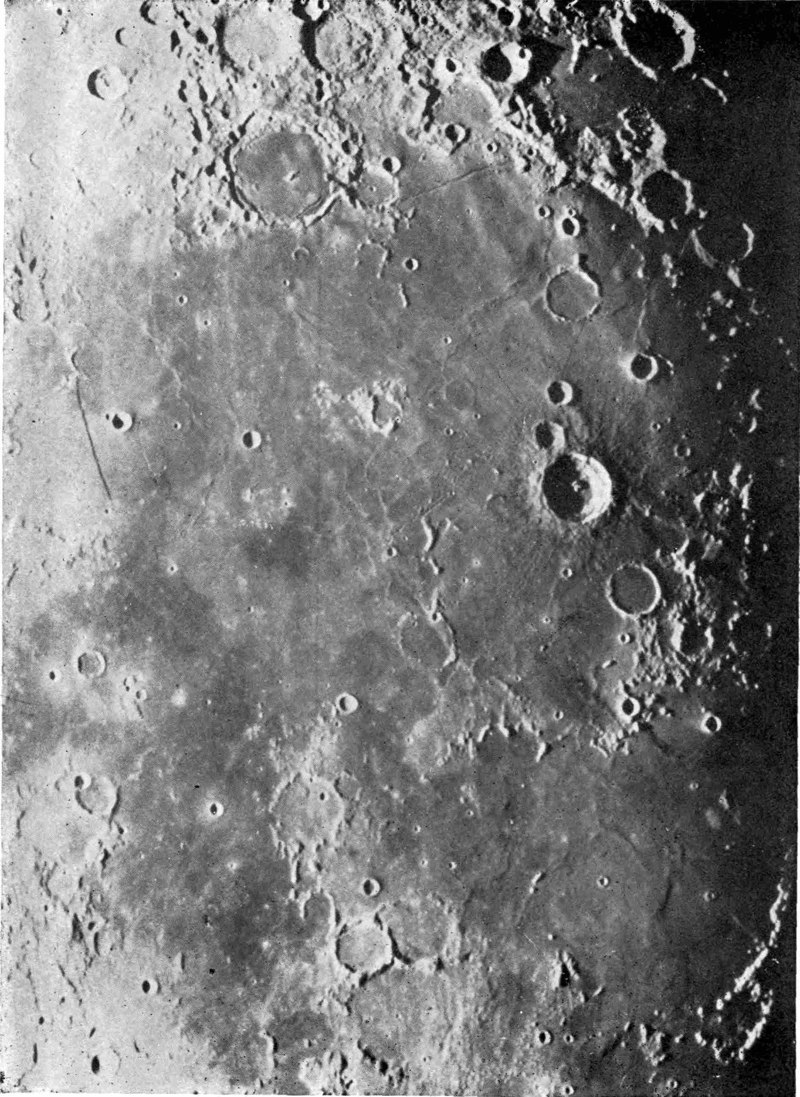

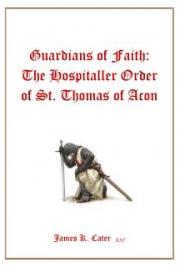

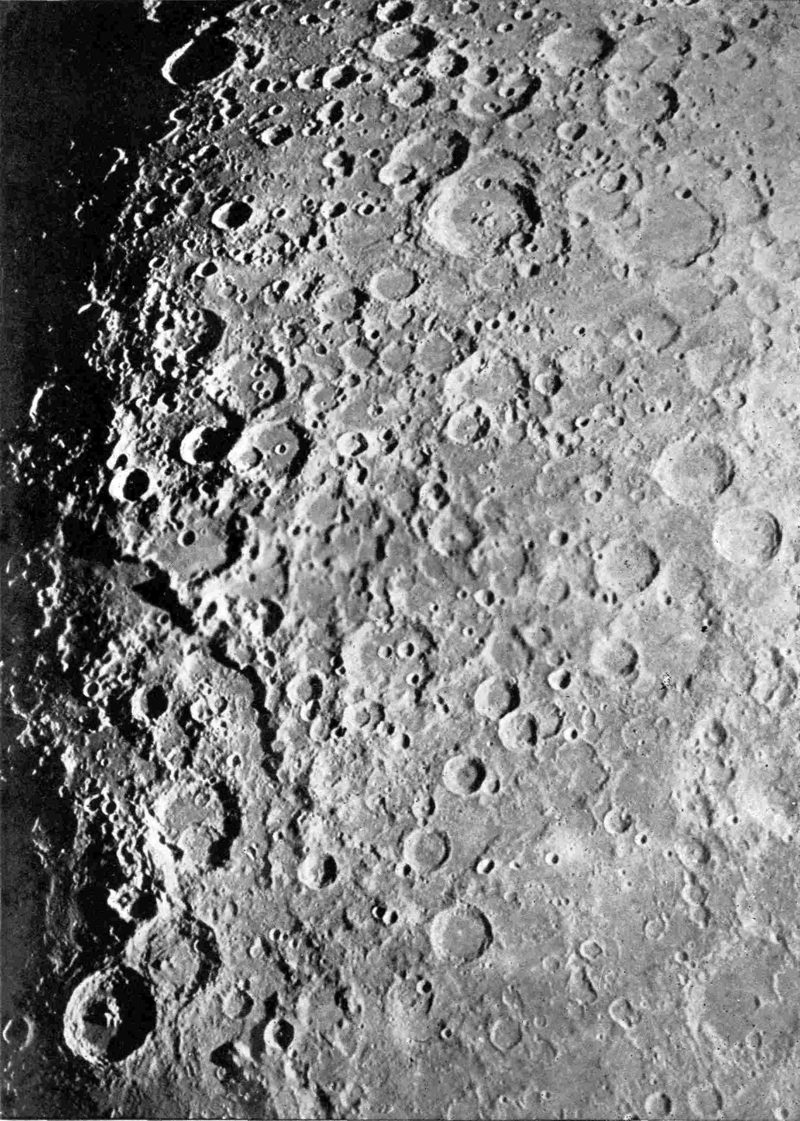

“The series of photographs that we are now about to examine,” I began, “are on so large a scale that only a selected part of the moon is seen in each of them. But within the restricted limits of these pictures the amount of detail shown is truly astonishing, far more indeed than can be found on the most elaborate lunar charts. These photographs were made by Mr. Ritchey with the great 40-inch telescope of the Yerkes Observatory. Many more besides those that we are going to look at were taken by him, but I have selected, where choice was difficult, six which seemed to me to be of special interest. We shall begin with one which covers the larger part of the Mare Nubium, in the southeastern quarter of the moon. You certainly must remember the Mare Nubium, for it forms the head of the ‘dark woman’ whom you discovered in the moon last evening, and if you will hold this photograph at arm’s length you will see that her face is unmistakably stamped upon it.”

“I am greatly flattered,” she replied, “that you should remember my discovery so well. I begin to feel hopeful that it may yet find a place in the books.”

“It certainly is as deserving of such a place as many things that get into books. You ought to find a suitable name for this woman in the moon.”

“If I believed myself capable of rivaling the man who christened the ‘Marsh of a Dream,’ I should surely try my hand at lunar nomenclature, but I fear that I should fall too far short of the ideal he has set up, and so I shall leave her nameless.”

“Permit me then to continue to call her the ‘dark woman’ whenever a reference to her may seem useful in fixing the localities that we shall talk about in this photograph. The most striking object shown in the picture is the great ring mountain Bullialdus which forms an extraordinary ornament on the top of the ‘dark woman’s’ ear. This photograph was taken when the line of sunrise ran just along the border between the Mare Nubium and the Oceanus Procellarum. The Mare Humorum is yet buried in night beyond the upper right-hand edge of the picture, but some of its bordering mountains and craters have been touched by the morning sunbeams. You will observe that a little more than half of the interior of Bullialdus—which, by the way, I did not mention by name when we were studying the series of phase photographs—is yet filled with shadow, but its double-headed central peak rises clear and bright in the sunlight. The shadow of this central mountain can be seen projecting toward the east over the floor. The east wall, which is distinctly terraced, lies in full sunshine, and the light streaming over the lofty crest of the western wall touches the floor on its eastern half. The steep outer slopes that lead up to the western rampart, and the deep parallel ravines cut near the crest are clearly shown. The distance across the ring from the summit of the wall on one side to that on the other is 38 miles. The depth of the depression is 8,000 feet below the crest of the walls, but the latter rise only 4,000 feet above the level of the Mare Nubium outside, so that Bullialdus is an excellent example of the characteristic form of the lunar volcano, which I tried to illustrate for you last evening. The central mountain is 3,000 feet high. East of the south point of the ring a shadow shows the existence of a profound cleft in the wall, while a little west of south appears a smaller crater ring very black with shadow, except on its eastern side. If we stood on the Mare Nubium and looked toward Bullialdus and its neighbor from a distance of 25 or 30 miles they would resemble a double, flat-topped mountain, with its serrated crests connected by a high neck. The summit of one of the little peaks shown in the photograph in the plain just west of Bullialdus would form an excellent point of observation. Still farther south stands another crater ring most of whose interior is also, at present, filled with shadow. East of this, and a little farther south, is still a third ring of similar aspect, from which a curious range of hills runs southward. Returning to Bullialdus you will notice the radiating lines of hills that surround it, and particularly a more lofty and broken range which runs eastward.”

BULLIALDUS AND THE MARE NUBIUM.

“Bullialdus verily frightens me!” exclaimed my friend. “What an unearthly look it has! The longer I regard it the stronger becomes the indescribable impression that it produces. I begin to understand now what you meant when you promised to find a history in the moon. Truly there never can have been such another history. I almost feel that I do not care whether the moon ever had inhabitants or not. Its own story is more fascinating than that of any puny race of beings, passing their ephemeral lives upon its wonderful surface, could possibly be.”

“I am glad,” I replied, “that you have begun to enter into the spirit of those who long and carefully study the earth’s satellite. You see now, that it is not necessary to the astronomer to find evidences either of former or of present life upon the moon in order to stimulate his zeal. For him, as you have yourself intimated, the relics of its past history, which this little world in the sky exhibits so abundantly, are of higher interest than any story of human empire, for they have an incomparably vaster theme. But to lighten our labor a little, let me once more refer to the ‘dark woman,’ whose features, like the outlines of a constellation, serve for points of reference. I began by remarking that Bullialdus seems to be placed just over her ear. Observe now that, taken together with its immediate surroundings, the great crater ring forms a kind of barbaric ear-ornament of most extraordinary form and richness of detail. The line of hills east of Bullialdus, of which I spoke a few minutes ago, connects the ring with a tumbled mass of mountains on the border of the Mare Humorum. These mountains run northward, or downward in the picture, for a distance of perhaps 150 miles, and then turn abruptly westward for a like distance; after which, in the form of a broken chain, constituting the eastern walls of a row of half-submerged ring plains, they change direction once more and run southward in the Mare Nubium. The whole system bears some resemblance to a gigantic buckle.”

“What is that curious object below Bullialdus which resembles an old-fashioned gold earring?”

“I was about to speak of that. It is a ring plain named Lubiniesky, about 23 miles in diameter with a wall a thousand feet in height, except in the direction of Bullialdus where it is broken down. The interior is very flat, and it forms a fine example of the half-submerged lunar volcanoes which abound in this hemisphere. It may have had a central mountain like Bullialdus, but if so it has been completely buried under the influx of molten lava or whatever it was that covered this part of the moon. The perfect form of Bullialdus in all its details when compared with the mere outline that remains of Lubiniesky indicates that the former probably burst forth after the inundation of liquid rock that drowned the latter. Thus we have in these two neighboring formations two chapters of lunar history which, like the monuments of Egypt, tell the story of widely separated epochs. The row of still more completely submerged crater rings westward from Lubiniesky and Bullialdus show by their condition that the depth of the lava flood was probably greater in their vicinity than it was farther eastward.

“Now look southward from Bullialdus, at a distance about twice as great as that of Lubiniesky and you will see another partially submerged ring, with a more serrated crest. The name of this is Kies. It is remarkable for the lofty mountain spur which sets off from its southern wall, and also for the fact that one of the bright streaks from Tycho—one of a parallel pair that I pointed out to you last evening—traverses its flat floor and continues on, broadening as it goes, to a deep crater ring which we have already noticed, southeast of Bullialdus.

“South of Kies, at the edge of the Mare Nubium, is a lofty mountain range whose summits and slopes are very bright in the sunrise. At one point a great pass breaks through these mountains, leading to a sort of bay shut in on all sides by precipices and the walls of gigantic crater rings. The large crater ring at the eastern corner of this bay is Capuanus. The smaller ring on its western side with a conspicuous crater on its eastern wall is Cichus. Notice the fine shadow that Cichus casts, whose pointed edge is evidently due to the little crater on the wall. That ‘little’ crater is six miles across! The twin rings apparently terminating the mountain mass northeast of the bay are Mercator and Capuanus. Between these and Kies you perceive two short ranges of small mountains and then a kind of round swelling of the surface of the plain resembling a great mound. These formations are rare on the moon. They look like bubbles raised by imprisoned gases. The United States Geological Survey has discovered something similar in form, but infinitely inferior in magnitude, in the great mud bubbles that rise to the surface of the Gulf of Mexico off the mouth of the Mississippi River. But I do not mean to aver that the two phenomena are similar in origin.

“Near the southern shore of the Mare Nubium appears a long, dark line which starts at the edge of a crater ring, crosses the southern arm of the ‘sea,’ evidently penetrates the bordering mountains, and reappears traversing the dark bay near its northern edge, cleaving both walls of a small crater ring in its way.

“I should weary you, perhaps, with too much detail if I undertook to identify all of the prominent objects in this photograph. Returning to the southern shore of the Mare Nubium, I shall simply call your attention to the very large ring plain with terraced walls and a peak a little east of its center. This is Pitatus. An enormous ravine breaks through its eastern side and connects it with a smaller ring from which the dark line already mentioned starts. This dark line represents one of the most remarkable clefts on the moon. It looks as though the crust had been split asunder there over a distance of at least 150 miles. It bears some resemblance to the great cañon near Aristarchus and Herodotus, except that the latter is very tortuous and this is nearly straight.”

“Have I not heard of something similar in connection with the California earthquake in 1906?” asked my friend.

“No doubt you are thinking of the great ‘fault’ which geologists have discovered off the Pacific coast of North America. There is perhaps some resemblance between these phenomena. Pitatus, I may add, is 58 miles in diameter. You will observe how its southern wall has apparently been broken down by the deluge of lava which buried so many smaller rings in the Mare Nubium. If you will now turn your attention to the left-hand side of the photograph, somewhat above the center, you will perceive a very strange object, the so-called ‘Straight Wall.’ It lies just west of a large conical crater pit which has a much smaller pit near its western edge. You might easily mistake the ‘Straight Wall’ for an accidental mark in the photograph. It is not absolutely straight, and near its southern end it makes a slight turn eastward and terminates in a curious, branched mountain, whose most conspicuous part is crescent-shaped. The wall is about 65 miles in length and 500 feet in height. It is as perpendicular on its east face as the Palisades on the Hudson. It is not a ridge of hills at all, but a place where the level of the ground suddenly falls away. Approaching it from the west you would probably be unaware of its existence until you stood upon its verge. The dark line that we see in the photograph is the shadow cast by the wall upon the lower plain. In the lunar afternoon the appearance is changed, and the face of the cliff is seen bright with sunlight. This curious object has attracted the attention of students of the moon for generations, and many speculations were formerly indulged in concerning its possible artificial origin. It has sometimes been called the ‘Lunar Railroad.’ Manifestly, whatever else it may be, it is not artificial. The closest analogy perhaps is with what we were speaking of a little while ago, a geological fault, that is to say, a line in the crust of the planet where the rocky strata have been broken across and one side has dropped to a lower level.

“The crater pit in the Mare Nubium, east of the ‘Straight Wall,’ is named Birt, and its twin, 75 miles farther east, is Nicollet. Look now at the hooked nose of your ‘dark woman.’ The huge wart upon it is a crater plain named Lassell. Between the lower end of the ‘Straight Wall’ and Lassell, and over the bridge of the ‘nose,’ a wedge-shaped mountain runs out into the mare. This is called the Promontorium Ænarium, and must have formed a magnificent outlook if ever a real ocean flowed at the foot of its cliffs. The ring with a crater on its wall below Lassell is Davy. You will note some very somber regions scattered over this part of the Mare Nubium. One of them forms the ‘dark woman’s’ eye, and just over it, like an eyebrow, is a curving range of hillocks, including some little craters. On the ‘cheek’—I am still utilizing the ‘dark woman’ as a kind of signboard—at the base of the ‘chin,’ appears a partly double range of large ring plains. The greatest of these, at the bottom, is named Fra Mauro, and you will notice within it a curious speckling of small craters. Adjoining Fra Mauro on the south are two intersecting rings, Barry being the name of the western and Bonpland that of the eastern one. The partially submerged ring is nameless, as far as I know, while the upper or southern member of the group, with a broad valley shut in between broken mountain walls opening out of its northern side, is Guerike. There is only one other object, on the extreme lower right-hand corner of the picture, to which I will ask your attention. It is a singular range of mountains thrown into a great loop at its northern end, and known as the Riphæan Mountains.”

“It seems to me,” said my friend, putting her elbow on the table, and leaning her head a little wearily on her hand, “that there is a great sameness in these lunar scenes—always crater rings with or without central mountains, always peaks and ridges and chasms and black shadows. Truly variety is lacking.”

“But what could you expect?” I replied. “Is it not enough to stimulate your curiosity that you are looking intimately into the details of a foreign world? When you go to Europe you see there mountains, plains, rivers, lakes, cities, people, absolutely identical in their main features with what you see in America. But you find them endlessly interesting because of their comparatively slight differences from similar things with which you are familiar, because of the great age of many of the objects to which your attention is directed, because of the long course of history which they represent, and principally, perhaps, because you are aware of the sensation of being far from home. It ought to be the same for you here on the moon. These things that we are looking upon belong to a globe suspended in space 239,000 miles from the earth. If the features of our globe are practically the same everywhere, differing only in the arrangement of their details, you should not be surprised at finding that nature does not vary from her rule of uniformity on the moon.

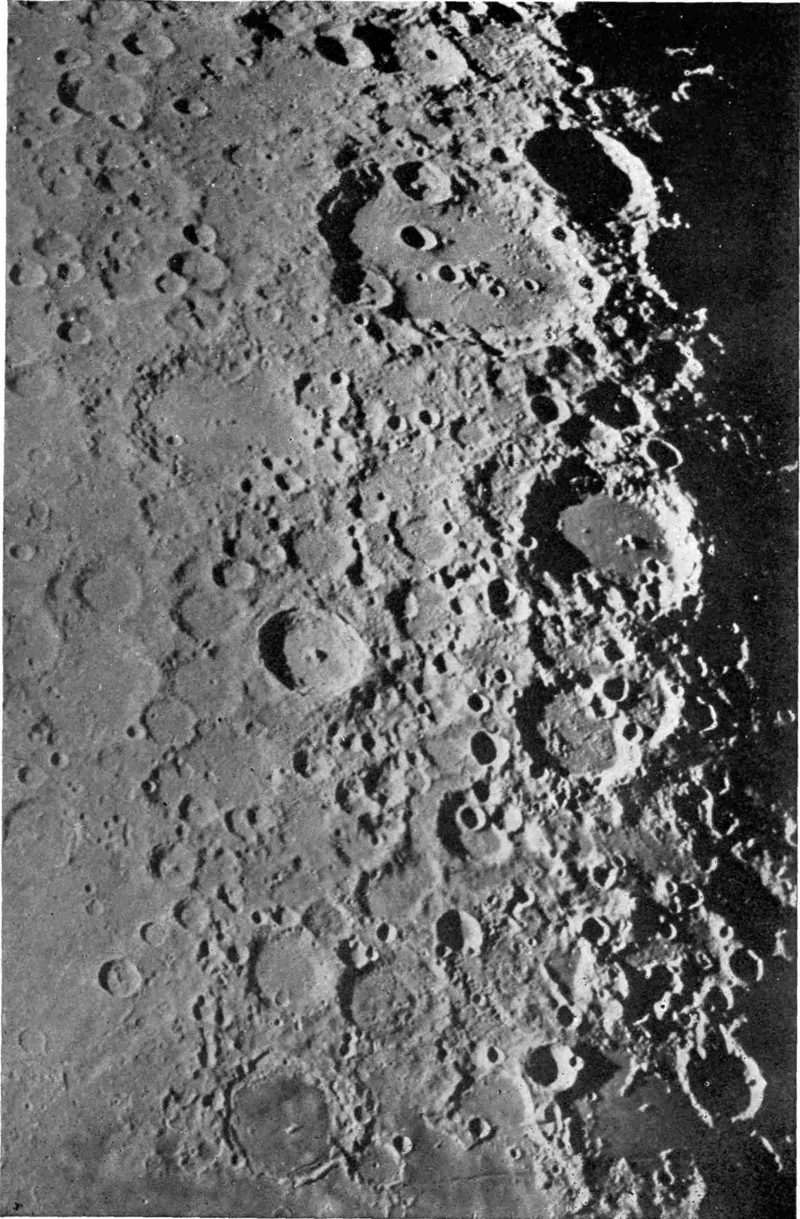

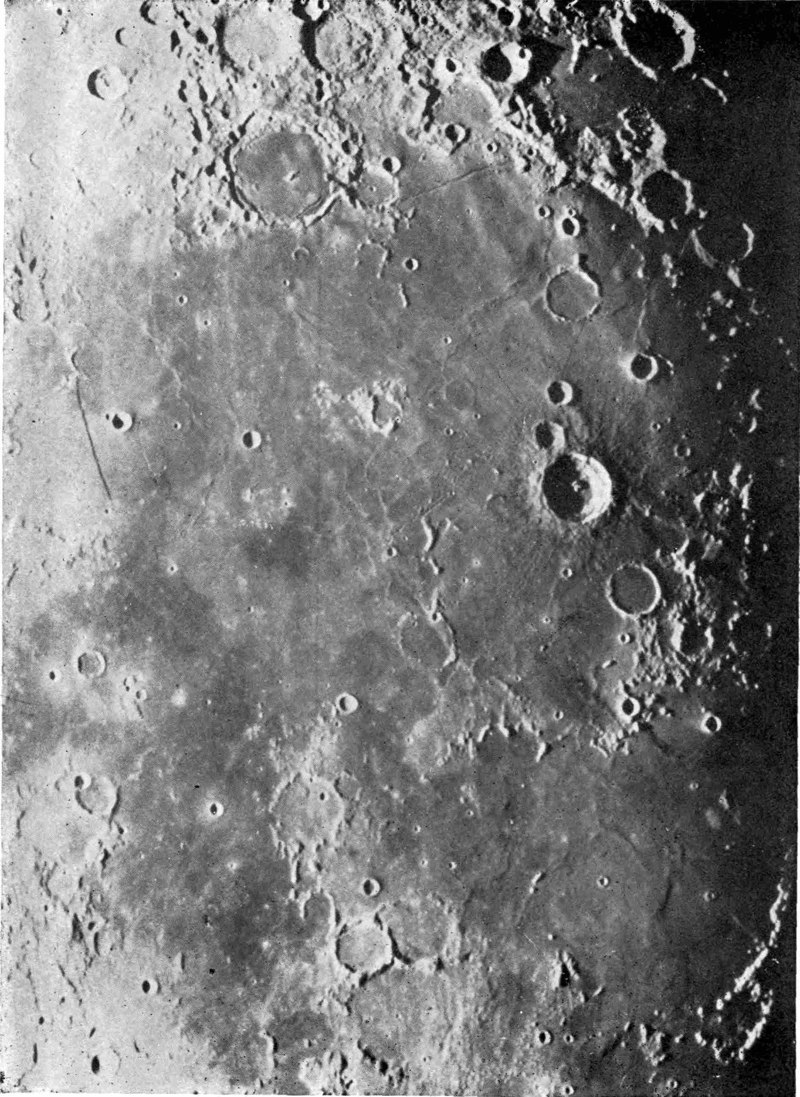

“In the next photograph of the series,” I continued, “we have a marvelous specimen of the lunar landscapes. It is perhaps the most rugged region on the moon. It includes two objects of supreme interest, Tycho, the ‘Metropolitan Crater,’ and Clavius, the most remarkable of the ring plains. You will no doubt recognize Tycho at a glance. It is near the center of the picture. Like the last photograph this one represents an early morning scene. The western wall of Tycho throws a broad, irregular crescent of shadow into the cavernous interior, but all of the eastern, northern, and southern sides of the wall are illuminated on their inner faces. The central mountain group is emphasized by its black shadow. A little close inspection reveals the existence of the complicated system of terraces by which the walls drop from greater to lesser heights until the deep sunken floor is reached. The diameter of Tycho is 54 miles, and it is at least 17,000 feet deep, measured from the summits of the peaks that tower on both the eastern and the western sides of its wall. The vast system of bright streaks radiating from Tycho is not seen here, the time when the photograph was made being too near the sunrise on this part of the moon. The dish-shaped plains crowded around Tycho form a remarkable feature of this part of the lunar surface. It would be useless to mention them all by name, and I shall ask your attention only to some of the principal ones.”

“Thank you for being so considerate,” said my friend, smiling. “I am sure that I should forget the names as fast as you mentioned them.”

TYCHO, CLAVIUS, AND THEIR SURROUNDINGS.

“Oh, I have no fault to find with your memory,” I replied. “I doubt if many selenographers could recall them without referring to a chart. Let us begin with the greatest of all, Clavius, which, you see, is near the top of the picture. I think I told you before that Clavius is more than 140 miles across. The great plain within the walls sinks 12,000 feet below the crest of the irregular ring, but the plateau outside, on the west, is almost level with the top of the ring. It is difficult to imagine a more wonderful or imposing spectacle than that which Clavius would present to a person approaching it from the western side, and arriving at about the time when this photograph was made, on the top of the wall. Notice how in one place the summit of a ridge, standing off on the inner side of the western wall, has come into the sunlight, and think of the frightful chasm that must yawn between. Clavius is so enormous that the two crater rings, each with a central mountain standing on its wall, seem very small in comparison with the giant that carries them, and yet they are 25 miles in diameter! Stretched out into a straight line, the tremendous wall of Clavius would form a range of towering mountains, extending as far as from Buffalo to New York. Look at the curved row of craters, the smallest larger than any on the earth, which runs across the interior. In addition to these there are many smaller craters and mountains standing on the vast sunken plain, some of them looking like mere pinholes, and yet all of really great size.”

“Truly,” interrupted my listener, “the giantism—I think that is the word you employ—the giantism of the moon appalls me! How can I ever think, again, that the so-called great spectacles of nature on the earth are really great? You have destroyed my sense of proportion. Such immense things standing on a world so small as the moon—why it seems contrary to nature’s laws.”

“I have already told you that the very smallness of the moon may be the underlying cause of the greatness of her surface features. And I may now add that if your imagined inhabitants ever existed they, too, may have been affected with ‘giantism.’ A man could be 36 feet tall on the moon and well proportioned at that, without losing anything in the way of activity.”

“Indeed! You almost make me hope that there never were such inhabitants, for what beauty could there be in a human being as tall as a tree?”

“Very little to our eyes, perhaps. You recall the impressions of Gulliver in the land of the Brobdingnags. However, they are not my inhabitants but yours, and if the law of gravitation says that they must have been twelve yards tall, then twelve yards tall they were. Take comfort, nevertheless, in the reflection that, after all, we cannot positively assert that gravitation alone governs the size of living beings on any particular world. We have microscopic creatures as well as whales and elephants on the earth, and human stature itself is very variable.”

“Thank you, again. You have saved my lunarians. And now please tell me what is that frightful black chasm above Clavius?”

“It is a ring plain named Blancanus, 50 miles in diameter, and exceedingly deep. It is so black and terrible because complete night yet reigns within it, except on the face of its eastern wall. It is really a magnificent formation when well lighted, but like so many other great things it suffers through its nearness to the overmastering Clavius. When Goliath was in the field his fellow Philistines cut but a sorry figure. Look at the marvelous region just below Blancanus and imagine yourself entangled in that labyrinth! You would have but a small chance for escape, I fancy.”

“I am sure I should never have the heart to even try to get out of it. One might as well give up at once.”

“Yes, you are probably right. But I will direct you to something not quite so frightful, although still very formidable in appearance. Still farther below you observe a huge ring plain whose eastern wall is brightly illuminated, while nearly all the interior plain, although comparatively dark in tone, lies in the sunshine. It is Longomontanus. I pointed it out to you in one of the smaller photographs. Longomontanus is 90 miles across and 13,000 or 14,000 feet deep, measured from its loftiest bordering peaks. The very irregular formation below it is Wilhelm I. It is remarkable for the mountainous character of its interior.”

“For what William was it named?”

“I do not know. We are now near the southern border of the region that we inspected in the preceding photograph. In the lower part of this picture you perceive some of the projecting bays of the Mare Nubium, and you can see again the remarkable cleft of which I spoke. The large ring near the bottom of the picture is Pitatus with its smaller neighbor Hesiodus. It is from the eastern side of the latter that the cleft apparently starts. Pitatus, you see, has a central peak, while Hesiodus, as if for the sake of contrast, possesses only a central crater pit. The ravine connecting the two is plainly visible. Toward the east you will recognize again Cichus, with its crater on the wall and its broad shadow with a sharp point, while still farther east, on the very edge of night, yawns Capuanus. The two walled plains above Pitatus are Gauricus on the left and Wurzelbauer on the right. The hexagonal shape of the former is very striking. This is a not uncommon phenomenon where the lunar volcanoes and rings are closely crowded, and it suggests the effect of mutual compression, like the cells of a honeycomb. Away over in the northwestern corner is a vast plain marked by a conspicuous crater ring which bears the startling name of Hell. It borrows its cognomen, however, from an astronomer, and not, as you might suppose, from Dante’s ‘Inferno.’

“Before quitting this photograph permit me to recall you to the neighborhood of Tycho and Clavius. To the left of a line joining them you will perceive a flat, oval plain with a much broken mountain ring. This is Maginus. Last evening while we were looking at one of the smaller photographs I pointed it out under a more favorable illumination, telling you at the same time that it possessed the peculiarity of almost completely disappearing at Full Moon. Already, although day has not advanced very far upon it, you observe that it has become relatively inconspicuous. This is a lesson in the curious effects of light and shadow in alternately revealing and concealing vast objects on the moon. You will notice that in many particulars Maginus resembles a reduced copy of Clavius. But the walls of Clavius are in a comparatively perfect condition while those of Maginus have apparently crumbled and fallen, destroyed by forces of whose nature we can only form guesses. Evidently the destruction has not been wrought, like that of some of the rings in the Mare Nubium, by an inundation of liquid rock from beneath the crust. It resembles the effects of the ‘weathering’ which gradually brings down the mountains of the earth, but if such agencies ever acted upon the moon, then it must have had an atmosphere and an abundance of water. In any event, here before us is another page of lunar chronology. Maginus is evidently far older than Clavius; Clavius is older than the craters standing on its own walls.”

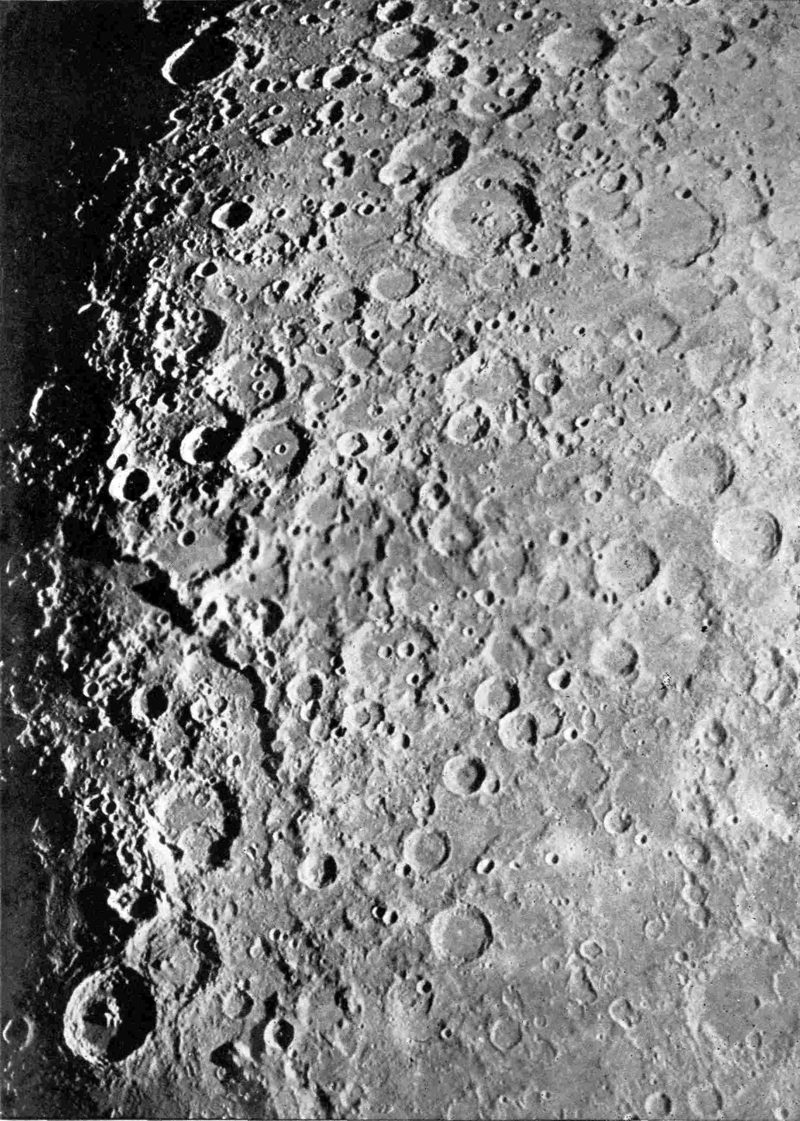

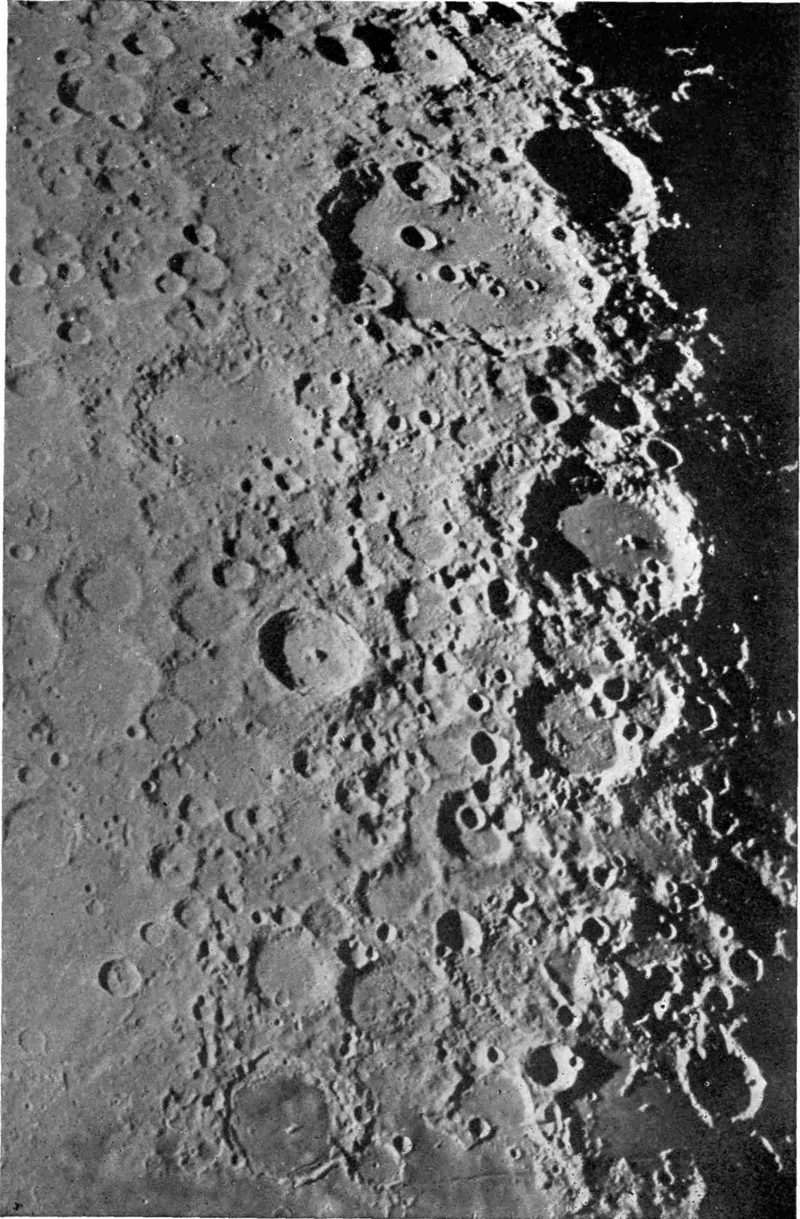

We now took up the third of the large photographs representing a part of the southwestern quarter of the moon, more extraordinary for its mountains, plateaus, and extinct volcanoes than the famous southwestern region of the United States.

“Here is something that you will surely recognize without any assistance,” I said. “In the lower left-hand corner of the picture is the great three-link chain of crater rings, of which Theophilus is the principal and most perfect member.”

“Oh, I recall them well,” replied my friend. “And yet they do not appear to me exactly the same as when I saw them before.”

THE GREAT SOUTHWEST ON THE MOON.

“One reason for that is because this photograph represents them on a much larger scale, and with infinitely more detail. Another reason is that now we are looking at them in the lunar afternoon instead of the lunar morning. We are going to see them represented on a still larger scale, presently, but there are many things in this picture well worthy of study. Advancing from the west, the line of night has fallen over the extreme eastern border of the Mare Nectaris, and the shadows thrown by the setting sun point westward. Observe how beautifully the brightly illuminated terraces and mighty cliffs of the western wall of Theophilus contrast with the black shadow that projects over half of the interior from the sharp verge of the eastern wall. The complicated central mountain is particularly well shown. The loftiest peak of this mountain mass, which covers 300 square miles, is 6,000 feet in height. You will see its shadow reaching the foot of the western wall. Theophilus is 64 miles in diameter, ten miles more than Tycho, and it is deeper than Tycho, the floor sinking 18,000 feet below the top of the highest point on the western wall. If it were the focus of a similar ray system it would deserve to be called the ‘Metropolitan Crater’ rather than Tycho. Plainly, Theophilus was formed later than its neighbor Cyrillus, because the southwestern wall of the latter has been destroyed to make room for the perfect ring of Theophilus.

“The interior of Cyrillus, you will observe, is very different from that of Theophilus. The floor is more irregular and mountainous. The wall, also, is much more complex than that of Theophilus. The broken state of the wall in itself is an indication of the greater age of Cyrillus. On the south an enormous pass in the wall of Cyrillus leads out upon a mountain-edged plateau which continues to the wall of the third of the great rings, Catharina. This formation seems to be of about the same age as Cyrillus, possibly somewhat older. Its wall is more broken and worn down, and the northern third of the inclosure is occupied by the wreck of a large ring. Observe the curious row of relatively small craters, with low mountain ranges paralleling them, which begins at the southwestern corner of Cyrillus and runs, with interruptions, for 150 miles or more. South of this is a broad valley with small craters on its bottom, and then comes an elongated mountainous region with a conspicuous crater in its center, beyond which appears another valley, which passes round the east side of Catharina, where it is divided in the center by a short range of hills. The southeastern side of this valley is bounded by the grand cliffs of the Altai Mountains, which continue on until they encounter the eastern wall of the great ring of Piccolomini, whose interior appears entirely dark in the picture, only a few peaks on the wall indicating the outlines of the ring. The serrated shadow of these mountains, thrown westward by the setting sun, forms one of the most striking features of the photograph. The northeastern end of the chain also terminates at a smaller ring named Tacitus. You see that Riccioli was rather cosmopolitan in his tastes, since he has placed the name of a Roman historian also on the moon. Beginning at a point on the crest of the Altai range, south of Tacitus, is a very remarkable chain of small craters, which extends eastward to the southern side of a beautiful ring plain with a white spot in the center. This ring is named Abulfeda. The chain of small craters or pits to which I have referred continues, though much less conspicuous, across the valley that lies northwest of the Altais. It is a very curious phenomenon, and recalls the theory advocated by W. K. Gilbert, the American geologist, that the moon’s craters were formed not by volcanic eruptions but by the impact of gigantic meteorites falling upon the moon, and originating, perhaps, in the destruction of a ring which formerly surrounded the earth, somewhat as the planet Saturn is surrounded by rings of meteoric bodies, which may eventually be precipitated upon its surface. The moon is more or less pitted with craterlets in all quarters, but there are places where they particularly abound. On inspecting this photograph carefully you will perceive several rows of much larger pits, two or three of them in the upper half of the picture, and one below the center, crossing the little chain of pits that I have just mentioned. The linear arrangement of some of the ring plains is also very striking. In regard to the theory that the lunar craters were formed by the impact of falling masses I may mention that two distinguished French students of the moon