CHAPTER VI

THE BAGANDA TRIBE OF UGANDA

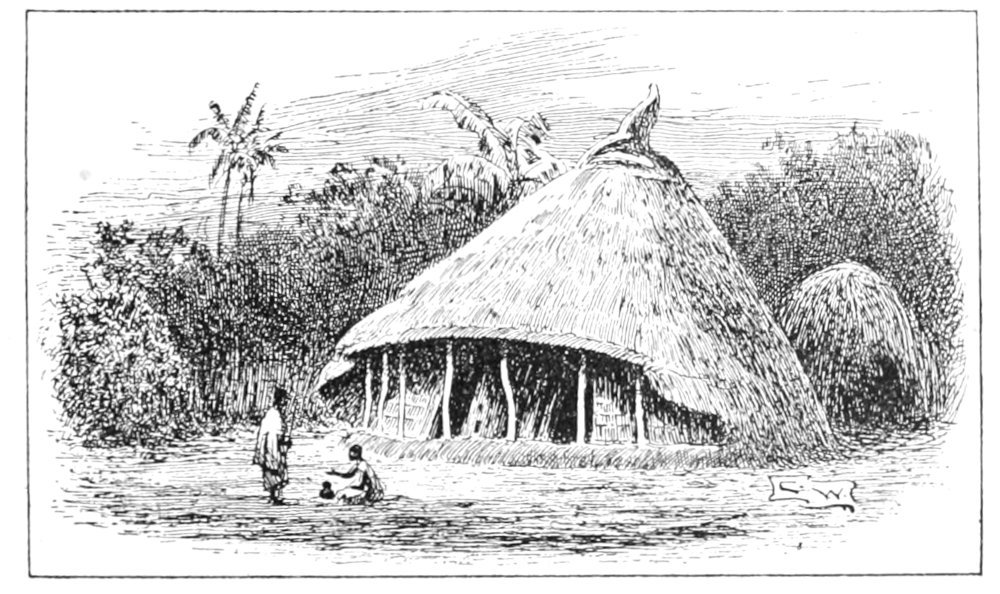

A BAGANDA HOUSE.

Half a century ago the Baganda might have been regarded as one of the most numerous tribes in Africa, but of late years losses through civil war, famine, and sleeping sickness have reduced the numbers to about a million. The Baganda are the most advanced in civilisation among all Bantu peoples, and for many years their dress, habits, and extreme politeness have been noted by travellers, who may now approach within 200 miles of Baganda territory by making a comfortable train journey of 600 miles from Mombasa to Lake Victoria Nyanza.

The greater part of the surface of Uganda is hilly, fertile, and well watered, and the slopes of the hills are cultivated by natives who grow plantain trees, maize, sugar-cane, tobacco, and coffee. Here and there dense forests are to be found, and in such regions the Baganda hunt the elephant, buffalo, and hippopotamus.

When speaking of this tribe, the Rev. J. Roscoe says: “The Baganda are the only Bantu tribe in Eastern Equatorial Africa who do not mutilate their persons; they neither extract their teeth nor pierce their ear lobes”; nor do they practise any of the deformations which have been related in chapters concerning the Masai and Akikuyu.

There are to be found clans with Roman features, and others varying from this type to the broad nose and thick lips of a Negro; so too, in build there are tall athletic figures over six feet in height, while, on the other hand, there are thick-set short-built men only about five feet in height.

The colouring, too, varies from jet black to copper colour; and stranger still, there are some pure negroes whose skin colour is almost white. These people were at one time kept as curiosities in an enclosure near to the hut of a native king or great chief. The hair of the Baganda is invariably short, black, crisp and woolly; hair on the face is either shaved or pulled out, and any sign of beard or moustache is regarded as very ugly.

Naturally, in a country where big game abounds, hunting is not only a pastime of chiefs and nobles, but a very important means of obtaining a food supply. As a rule, elephant hunters were men who had been trained from very early childhood, so that they became close observers of these animals, followed every movement of the herd, and became adepts in launching spears from a secure position in the tops of lofty trees. The spear had a broad leaf-shaped blade six inches long, mounted on a thick wooden shaft, and a strong arm was necessary in order to deliver a powerful, accurate throw. The night before the hunt these spears were sharpened, then placed by the altar of Dungu, the god of hunting, to whom an offering of beer and a goat was made. At times the Baganda huntsman was more open in his methods of attack, and several natives, armed only with spears, would creep right up to the herd, and after launching their weapons would depend on rapid flight for safety.

Elephant traps were very common, and an unwary animal caught his feet in a cord which released a heavy spear from the branches above. All the hunters took up the chase of this wounded creature, which was followed until it fell exhausted. Foot traps, causing an animal to tumble on a sharp spear, placed point uppermost in a pit, were commonly used, and what seems most strange, the nerves from the tusks of a dead animal were always carefully buried. The Baganda are very superstitious, and it was thought that the ghost of an animal killed in the chase would attach itself to the buried nerves, instead of haunting the men who launched the spears or laid the traps.

Before hunting the lion or leopard, a chief would beat the war drum in order to collect his people, who often went forth a thousand strong. A few men followed the animal to its lair, then returned to their chief to report the exact position. This having been done, a noisy party, shouting and beating drums, surrounded the animal’s hiding-place. A trapped animal will, of course, fight very fiercely, after rushing first in one direction then in another trying to find a means of escape, and, as a rule, some one was severely wounded before the creature was killed with clubs and spears.

The hippopotamus was hunted, not for food, but because it proved such a danger to canoe men, and at night did great damage by wandering over cultivated plots of ground. A spear trap might be set in the path from a river to pastures, or harpoons were launched by men in canoes, which the animal frequently attacked and overturned.

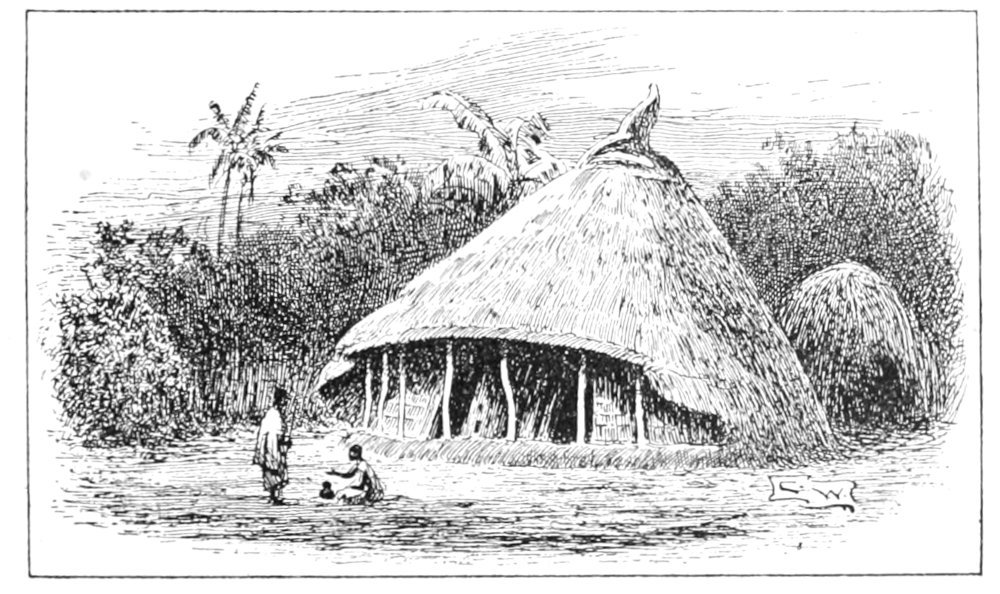

LIZARD-SKIN DRUM, LANGO TRIBE, UGANDA PROTECTORATE.

The Baganda live very largely on vegetable food, and, as is so often the case among primitive people, the women do all the field work. True, the husband clears the ground of all shrubs and tall grass, but when this work is done his wife performs all the digging, sowing, and collecting of the harvest. Ashes from burnt leaves, when washed in by the heavy rains, fertilise the soil, and success is sought by sacrificing a fowl and pouring out an offering of beer at the roots of trees, while the husband says: “Give me this land, and let it be fruitful, and let me build my house here, and have children.”

In addition to their hunting and agriculture, the Baganda are very fond of trade and barter, and in many villages there is a market-place where a salesman must pay fees in order to get permission to sell his wares. The king of the Baganda receives these market dues, which amount to one-tenth of the produce sold, and as the produce offered for sale comprises animals, fish, eggs, salt, sweet potatoes, peas, beans, pottery, tobacco, axes, hoes, and rope, the amount of money due to royalty must be very great. At the end of a busy market day many boys are ready to clean up the market-place, in reward for which they get scraps of meat from the slaughter-house, a few coffee berries, or a little salt. Money consists of cowrie shells, two hundred of which are needed to buy a large earthenware pot; five to ten are given for a tobacco pipe; and in striking such bargains as these the busy marketing day soon draws to a close.