CHAPTER VI

THE HOLY WAR

WHEN the Shawia tribesmen made their first attacks upon the French at Casablanca they were thoroughly confident of their own prowess and of the protection of Allah. They had often, before the coming of the French, called the attention of Europeans to the fact that salutes of foreign men-of-war entering port were not nearly so loud as the replies from their own antiquated guns—always charged with a double load of powder for the sake of making noise. But they have come to realise now that Christian ships and Christian armies have bigger guns than those with which they salute, and the news that Allah, whatever may be His reason, is not on the side of the noisy guns has spread over a good part of Morocco.

The Arabs now seldom try close quarters with the French, except when surrounded or when the French force is very small and they are numerous; and as I have indicated before, their defence is most ineffective. One morning on a march towards Mediuna I sat for an hour with the Algerians, under the war balloon, watching quietly an absurd attack of the tribesmen. From the crest of a hill, behind which they were lodged, they would ride down furiously to within half a mile of us, and turning to go back at the same mad pace, discharge a gun, without taking aim, at the balloon, their special irritation. It was all picturesque, but like the gallant charge of the brave Bulgarian in ‘Arms and the Man,’ entirely ridiculous. If the Algerians had been firing at the time, not one of them would have got back over their hill.

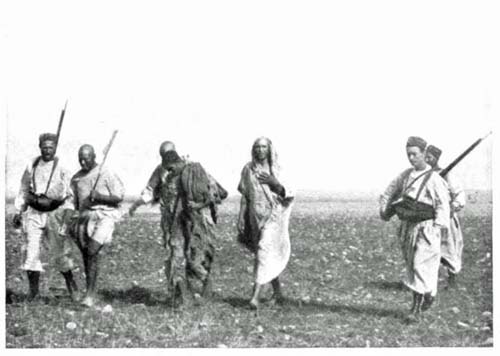

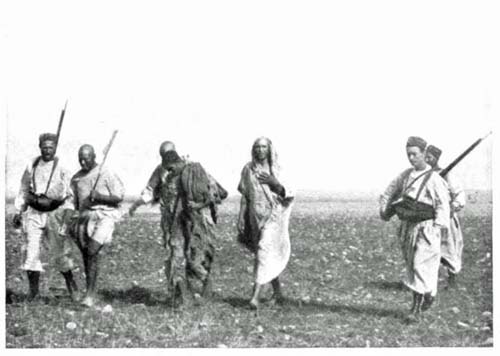

ARAB PRISONERS WITH A WHITE FLAG.

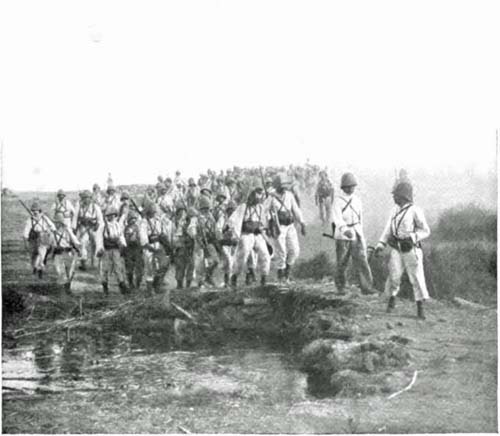

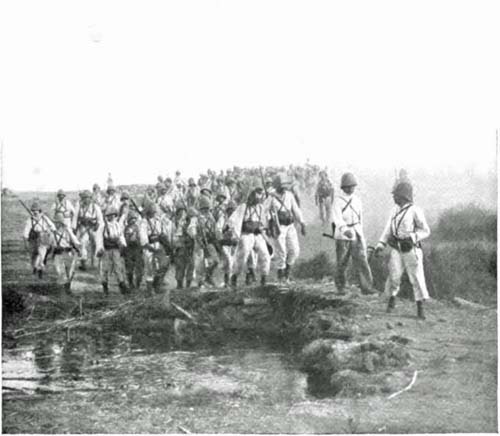

A COLUMN OF THE FOREIGN LEGION.

The reports in the London papers of serious resistance on the part of the Moors are seldom borne out by facts. Most of the despatches, passing through excitable Paris, begin with startling adjectives and end with ‘Six men wounded.’ Here, for instance, are the first and the last paragraphs of the Paris despatch describing the first taking of Settat, which is over forty miles inland and among the homes of the Shawia tribesmen. It is headed:

‘A Sixteen-Hour Fight.

‘At eight a.m. yesterday the French columns opened battle in the Settat Pass. The enemy offered a stubborn resistance, but was finally repulsed, after a fight lasting until midnight. Settat was occupied and Muley Rechid’s camp destroyed.

‘There were several casualties on the French side.... The enemy’s losses were very heavy. The fight has produced a great impression among the tribes.’

The Arab losses under the fire of the French 75-millimètre guns and the fusillade of the Foreign Legion and the Algerians, many of them sharpshooters, are usually heavy where the Arabs attempt a serious resistance. I should say it would average a loss on the part of the Moors of fifty dead to one French soldier wounded. Moreover, when a Moor is badly wounded he dies, for the Moors know nothing of medicine, and the only remedies of which they will avail themselves are bits of paper with prayers upon them, written by shereefs; these they swallow or tie about a wound while praying at the shrine of some departed saint. It has seemed to me a wanton slaughter of these ignorant creatures, but if the French did not mow them down, the fools would say they could not, and would thank some saint for their salvation.

The arms of the Arabs are often of the most ineffective sort, many of them, indeed, made by hand in Morocco. While I was with the French army on one occasion we found on a dead Moor (and it is no wonder he was dead) a modern rifle, of which the barrel had been cut off, evidently with a cold chisel, to the length of a carbine. The muzzle, being bent out of shape and twisted, naturally threw the first charge back into the face of the Moor who fired it. I have seen bayonets tied on sticks, and other equally absurd weapons.

There are in Morocco many Winchester and other modern rifles, apart from those with which the Sultan’s army is equipped. Gun-running has long been a profitable occupation amongst unscrupulous Europeans of the coast towns, the very people for whose protection the French invasion is inspired. A man of my own nationality told me that for years he got for Winchesters that cost him 3l. as much as 6l. and 8l. The authorities, suspecting him on one occasion, put a Jew to ascertain how he got the rifles in. Suspecting the Jew, the American informed him confidentially, ‘as a friend,’ that he brought in the guns in barrels of oil. In a few weeks five barrels of oil and sixteen boxes of provisions arrived at —— in one steamer. The American went down to the custom-house, grinned graciously, and asked for his oil, which the Moors proceeded to examine.

‘No, no,’ said the American.

The Moors insisted.

The American asked them to wait till the afternoon, which they consented to do; and after a superficial examination of one of the provision boxes, a load of forty rifles, the butts and barrels in separate boxes, covered with cans of sardines, tea, sugar, etc., went up to the store of the American.

It was more profitable to run in guns that would bring 8l., perhaps more, than to run in 8l. worth of cartridges, and after the Moors had secured modern rifles they found great difficulty in obtaining ammunition, which for its scarcity became very dear. For that reason many of them have given up the European gun and have gone back to the old flintlock, made in Morocco, cheaper and more easily provided with powder and ball.

Ammunition is too expensive for the poverty-stricken Moor to waste much of it on target practice, and when he does indulge in this vain amusement it is always before spectators, servants and men too poor to possess guns; and in order to make an impression on the underlings—for a Moor is vain—he places the target close enough to hit. The Moor seldom shoots at a target more than twenty yards off.

Even the Sultan is economical with ammunition. It is never supplied to the Imperial Army—for the reason that soldiers would sell it—except just prior to a fight. It is told in Morocco that when Kaid Maclean began to organise the army of Abdul Aziz he was informed that he might dress the soldiers as he pleased—up to his time they were a rabble crew without uniforms—but that he need not teach them to shoot. Nor have they since been taught to shoot.

I am of opinion that the French army under General d’Amade, soon to number 12,000 or 13,000 men, could penetrate to any corner of Morocco with facility, maintaining at the same time unassailable communication with their base. A body of the Foreign Legion three hundred strong could cut their way across Morocco. With 60,000 men the French can occupy, hold, and effectively police—as policing goes in North Africa—the entire petty empire. Such an army in time could make the roads safe for Arabs and Berbers as well as for Europeans, punishing severely, as the French have learned to do, any tribe that dares continue its marauding practices and any brigand who essays to capture Europeans; and as for the rest, the safety of life and property within the towns and among members of the same tribes, the instinct of self-preservation among the Moors themselves is sufficient. There is no danger for the French in Morocco.

Nevertheless, their task is not an easy one. Conservatism at home and fear of some foreign protest has kept them from penetrating the country, as they must, in order to subdue it. So far they have made their power felt but locally, and though they have slain wantonly thousands of Moors, their position to-day is to all practical purposes the same as it was after the first engagements about Casablanca. For four months General Drude held Casablanca, with tribes defeated but unconquered all about him. With the new year General Drude retired and General d’Amade took his place, and the district of operations was extended inland for a distance of fifty miles. But beyond that there are again many untaught tribes ranging over a vast territory.

If the French, from fear of Germany, do not intend to occupy all Morocco I can see for them no alternative but to recognise Mulai el Hafid, who as Sultan of the interior is inspiring the tribesmen to war. Hafid’s position, though criminal from our point of view, is undeniably strong.

On proclaiming himself sultan, he sought to win the support of the country by promising a Government like that of former sultans, one that cut off heads, quelled rebellions, and kept the tribes united and effective against the Christians. This was the message that his criers spread throughout the land; and the people, told that the French had come as conquerors, gave their allegiance to him who promised to save them. Hafid’s attitude towards the European Powers was by no means so defiant as he professed to his people. Emissaries were sent from Marakesh to London and Berlin to plead for recognition, but were received officially at neither capital. He then tried threats, and at last, in January, declared the Jehad, or Holy War. But that he really contemplated provoking a serious anti-Christian, or even anti-French, uprising could hardly be conceived of so intelligent a man; and hard after the news of this came an assuring message—unsolicited, of course—to the Legations at Tangier that his object was only to unite the people in his cause against his brother. Later, when one of his m’hallas took part in a battle against the French he sent apologies to them.

The Moors, the country over, have heard of the disasters to the Shawia tribes, at any rate, of the fighting. Knowing the hopelessness of combating the French successfully, the towns of the coast are willing to leave their future in the diplomatic hands of Abdul Aziz, in spite of their distaste for him and his submission to the Christians. Those of the interior, however, many of whom have never seen a European, have a horror of the French such as we should have of Turks, and they will probably fight an invasion with all their feeble force.

Because of the harsh yet feeble policy of the French, the trouble in Morocco, picturesque and having many comic opera elements, will drag on its bloody course yet many months.