CHAPTER I

OUT OF GIBRALTAR

IT was in August, 1907, one Tuesday morning, that I landed from a P. & O. steamer at Gibraltar. I had not been there before but I knew what to expect. From a distance of many miles we had seen the Rock towering above the town and dwarfing the big, smoking men-of-war that lay at anchor at its base. Ashore was to be seen ‘Tommy Atkins,’ just as one sees him in England, walking round with a little cane or standing stiff with bayonet fixed before a tall kennel, beside him, as if for protection, a ‘Bobbie.’ The Englishman is everywhere in evidence, always to be recognised, if not otherwise, by his stride—which no one native to these parts could imitate. The Spaniard of the Rock (whom the British calls contemptuously ‘Scorpion’) is inclined to be polite and even gracious, though he struggles against his nature in an attempt to appear ‘like English.’ Moors from over the strait pass through the town and leisurely observe, without envying, the Nasrani power, then pass on again, seeming always to say: ‘No, this is not my country; I am Moslem.’ Gibraltar is thoroughly British. Even the Jews, sometimes in long black gaberdines, seem foreign to the place. And though on the plastered walls of Spanish houses are often to be seen announcements of bull fights at Cordova and Seville, the big advertisements everywhere are of such well-known British goods as ‘Tatcho’ and ‘Dewar’s.’

I have had some wonderful views of the Rock of Gibraltar while crossing on clear days from Tangier, and these I shall never forget, but I think I should not like the town. No one associates with the Spaniards, I am told, and the other Europeans, I imagine, are like fish out of water. They seem to be of but two minds: those longing to get back to England, and those who never expect to live at home again. Most of the latter live and trade down the Moorish coast, and come to ‘Gib’ on holidays once or twice a year, to buy some clothes, to see a play, to have a ‘spree.’ Of course they are not ‘received’ by the others, those who long for England, who are ‘exclusive’ and deign to meet with only folk who come from home. In the old days, when the Europeans in Morocco were very few, it was not unusual for the lonesome exile to take down the coast with him from ‘Gib’ a woman who was ‘not of the marrying brand.’ She kept his house and sometimes bore him children. Usually after a while he married her, but in some instances not till the children had grown and the sons in turn began to go to Gibraltar.

My first stop at the Rock was for only an hour, for I was anxious to get on to Tangier, and the little ‘Scorpion’ steamer that plied between the ports, the Gibel Dursa, sailed that Tuesday morning at eleven o’clock. I seemed to be the only cabin passenger, but on the deck were many Oriental folk and low-caste Spaniards, not uninteresting fellow-travellers. Though the characters of the North African and the South Spaniard are said to be alike, in appearance there could be no greater contrast, the one lean and long-faced, the other round-headed and anxious always to be fat. Neither are they at all alike in style of dress, and I had occasion to observe a peculiar difference in their code of manners. I had brought aboard a quantity of fresh figs and pears, more than I could eat, and I offered some to a hungry-looking Spaniard, who watched me longingly; but he declined. On the other hand a miserable Arab to whom I passed them at once accepted and salaamed, though he told me by signs that he was not accustomed to the sea and had eaten nothing since he left Algiers. As I moved away, leaving some figs behind, I kept an eye over my shoulder, and saw the Spaniard pounce upon them.

The conductor, or, as he would like to be dignified, the purser, of the ship, necessarily a linguist, was a long, thin creature, sprung at the knees and sunk at the stomach. He was of some outcast breed of Moslem. Pock-marked and disfigured with several scars, his appearance would have been repulsive were it not grotesque. None of his features seemed to fit. His lips were plainly negro, his nose Arabian, his ears like those of an elephant; I could not see his eyes, covered with huge goggles, black enough to pale his yellow face. Nor was this creature dressed in the costume of any particular race. In place of the covering Moorish jeleba he wore a white duck coat with many pockets. Stockings covered his calves, leaving only his knees, like those of a Scot, visible below full bloomers of dark-green calico. On his feet were boots instead of slippers. Of course this man was noisy; no such mongrel could be quiet. He argued with the Arabs and fussed with the Spaniards, speaking to each in their own language. On spying me he came across the ship at a jump, grabbed my hand and shook it warmly. He was past-master at the art of identification. Though all my clothes including my hat and shoes had come from England—and I had not spoken a word—he said at once, ‘You ’Merican man,’ adding, ‘No many ’Merican come Tangier now; ’fraid Jehad’—religious war.

‘Ah, you speak English,’ I said.

‘Yes, me speak Englis’ vera well: been ’Merica long time—Chicago, New’leans, San ’Frisco, Balt’more, N’York’ (he pronounced this last like a native). ‘Me been Barnum’s Circus.’

‘Were you the menagerie?’

The fellow was insulted. ‘No,’ he replied indignantly, ‘me was freak.’

Later when I had made my peace with him by means of a sixpence I asked to be allowed to take his picture, at which he was much flattered and put himself to the trouble of donning a clean coat; though, in order that no other Mohammedan should see and vilify him, he would consent to pose only on the upper-deck.

Sailing from under the cloud about Gibraltar the skies cleared rapidly, and in less than half-an-hour the yellow hills of the shore across the strait shone brilliantly against a clear blue sky. There was no mistaking this bit of the Orient. For an hour we coasted through the deep green waters. Before another had passed a bleak stretch of sand, as from the Sahara, came down to the sea; and there beyond, where the yellow hills began again, was the city of Tangier, the outpost of the East. A mass of square, almost windowless houses, blue and white, climbing in irregular steps, much like the ‘Giant’s Causeway,’ to the walls of the ancient Kasbah, with here and there a square green minaret or a towering palm.

We dropped anchor between a Spanish gunboat and the six-funnelled cruiser Jeanne d’Arc, amid a throng of small boats rowed by Moors in coloured bloomers, their legs and faces black and white and shades between. While careful to keep company with my luggage, I managed at the same time to embark in the first boat, along with the mongrel in the goggles and a veiled woman with three children, as well as others. Standing to row and pushing their oars, the bare-legged boatmen took us rapidly towards the landing—then to stop within a yard of the pier and for a quarter of an hour haggle over fares. Three reals Moorish was all they could extort from the Spaniards, and this was the proper tariff; but from me two pesetas, three times as much, was exacted. I protested, and got the explanation, through the man of many tongues, that this was the regulation charge for ‘landing’ Americans. In this country, he added from his own full knowledge, the rich are required to pay double where the poor cannot. While the Spaniards, the freak and I climbed up the steps to the pier, several boatmen, summoned from the quay, came wading out and took the woman and her children on their backs, landing them beyond the gate where pier-charges of a real are paid.

At the head of the pier a rickety shed of present-day construction, supported by an ancient, crumbling wall, is the custom-house. Not in anticipation of difficulty here, but as a matter of precaution, I had stuffed into my pockets (knowing that my person could not be searched) my revolver and a few books; and to hide these I wore a great-coat and sweltered in it. Perhaps from my appearance the cloaked Moors, instead of realising the true reason, only considered me less mad than the average of my kind. At any rate they ‘passed’ me bag and baggage with a most superficial examination and not the suggestion that backsheesh would be acceptable.

But on another day I had a curious experience at this same custom-house. A new kodak having followed me from London was held for duty, which should be, according to treaty, ten per cent. ad valorem. It was in no good humour that after an hour’s wrangling I was finally led into a room with a long rough table at the back and four spectacled, grey-bearded Moors in white kaftans and turbans seated behind.

‘How much?’ I asked and a Frenchman translated.

‘Four dollars,’ came the reply.

‘The thing is only worth four pounds twenty dollars; I’ll give you one dollar.’

‘Make it three—three dollars, Hassani.’

‘No, one.’

‘Make it two—two dollars Spanish.’

This being the right tax, I paid. But I was not to get my goods yet; what was my name?

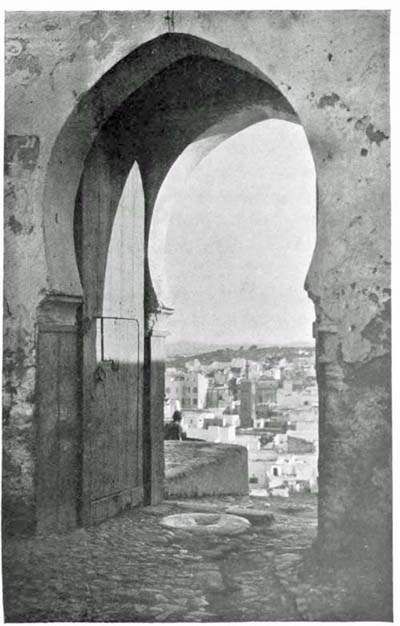

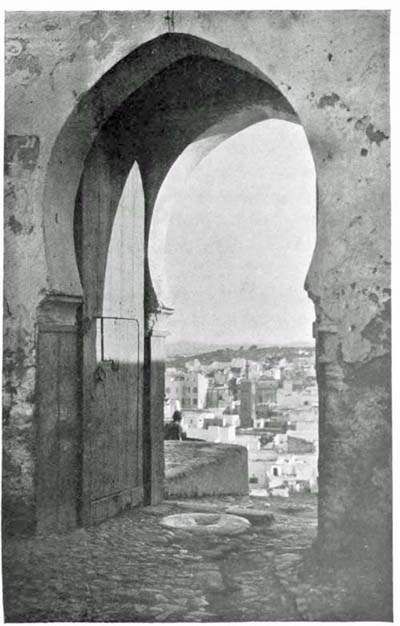

TANGIER THROUGH THE KASBAH GATE.

‘Moore.’

‘No, your name.’

‘I presented my card.’

‘Moore!’ A laugh went down the turbaned line.

A writer on the East has said of the Moors that they are the Puritans of Islam, and the first glimpse of Morocco will attest the truth of this. Not a Moor has laid aside the jeleba and the corresponding headgear, turban or fez. In the streets of Tangier—of all Moorish towns the most ‘contaminated’ with Christians—there is not a tramway or a hackney cab. Not a railway penetrates the country anywhere, not a telegraph, nor is there a postal service. Except for the discredited Sultan (whose ways have precipitated the disruption of the Empire) not a Moor has tried the improvements of Europe. It seems extraordinary that such a country should be the ‘Farthest West of Islam’ and should face the Rock of Gibraltar.