A TRIBUTE TO FLORENZ ZIEGFELD

THE incurable romanticist, George Jean Nathan, was the first to speak boldly in print and establish the rule of the silver-limbed, implacable Aphrodite in the theatre of Florenz Ziegfeld; and the equally incurable realist, Heywood Broun, has discovered that it isn’t so. Mr Nathan, obsessed by the idea that the world in general, and America in particular, goes to any extreme to conceal its interest in sex, really did a service to humanity by pointing out that there were beautiful girls in revues and that these girls constituted one of the main reasons for the attendance of men at the performances. Mr Broun, sensing a lack of abandon and frenzy in the modern bacchanale, says, simply, that it isn’t so, and implies that anyone who could get a thrill out of that—! Like the king in that story of Hans Christian Andersen, of which Mr Broun is inordinately fond, the girls haven’t any clothes on; and this little child, noticing the fact, is dreadfully disappointed.

Now Mr Ziegfeld is, in the opinion of those who work for him, a genius, and can well afford to say, “A plague on both your houses,” for he has built up what he himself calls a national institution, glorifying, not degrading, the American girl (pauvre petite). He can afford to look with complacency upon undergraduates charging upon his theatre in the anticipation of unholy delights, and forced to bear the clownings of Eddie Cantor or the wise sayings of Will Rogers; then he can turn to Dr John Roach Straton who, having heard from Mr Broun that the Follies are chaste, approaches to see some monstrosity of a classic ballet and hears the vast decent sensuality of a jazz number instead.

Mr Ziegfeld has lived through so much—through the period when it was believed indecent to be undressed and through the manlier period when nudity was contrasted with nakedness (it is the basis of a sort of Y. M. C. A. æsthetics that the nude is always pure) and through the long period, 1911–15, when the reviewers discovered the superior attractiveness of the stockinged leg; art in the shape of Joseph Urban has left a permanent mark upon him, and he has trafficked in strange seas for numbers and devices; what was vulgar and what was delicate, boresome and thrilling, have all passed through his hands; he has sent genius whistling down the wind to the vaudeville stage and built up new successes with secondary material; the storehouses are littered with the gaudy monuments of his imitators. And all the time the secret of his success has been staring Broadway in the face.

It is well to speak of Mr Ziegfeld’s success because in the last few years several things have happened to the revue; for almost as long as I remember the Ziegfeld Follies, I remember the Winter Garden opposition, the Passing Show, its exact antithesis.12 But lately there have arrived at least two productions which give every guaranty of permanence, in addition to some others which may turn out to be equally sure of survival. I mean the Music Box Revue and the Greenwich Village Follies. The Music Box is only in its third year; its chiefs assets are one of the most agreeable theatres in New York, assuring a reputation on the road, and first call on the still unsatisfied talents of Mr Irving Berlin. The Greenwich Village Follies, even if it lose its present director, John Murray Anderson, will continue to be successful for one of the strangest reasons in the world—its reputation for being “artistic.” The Winter Garden, the two Follies, and the Music Box, are the four points of the compass in this truly magnetic field. When the needle points due north, I usually find Mr Ziegfeld fairly snug under the Pole Star.

There are, if you count the chorus individually, about a hundred reasons for seeing a revue; there is only one reason for thinking about it, and that is that at one point, and only one point, the revue touches upon art. The revue as a production manifests the same impatience with half measures, with boggling, with the good enough and the nearly successful, which every great artist feels, or pretends to feel, in regard to his own work. It shows a mania for perfection; it aspires to be precise and definite, it corresponds to those de luxe railway trains which are always exactly on time, to the millions of spare parts that always fit, to the ease of commerce when there is a fixed price; jazz or symphony may sound from the orchestra pit, but underneath is the real tone of the revue, the steady, incorruptible purr of the dynamo. And with the possible exception of architecture, via the back door of construction, the revue is the most notable place in which this great American dislike of bungling, the real pleasure in a thing perfectly done, apply even vaguely to the arts.

If you can bring into focus, simultaneously, a good revue and a production of grand opera at the Metropolitan Opera House, the superiority of the lesser art is striking. Like the revue, grand opera is composed of elements drawn from many sources; like the revue, success depends on the fusion of these elements into a new unit, through the highest skill in production. And this sort of perfection the Metropolitan not only never achieves—it is actually absolved in advance from the necessity of attempting it. I am aware that it has the highest-paid singers, the best orchestra, some of the best conductors, dancers and stage hands, and the worst scenery in the world, in addition to an exceptionally astute impresario; but the production of these elements is so haphazard and clumsy that if any revue-producer hit as low a level in his work, he would be stoned off Broadway. Yet the Metropolitan is considered a great institution and complacently permitted to run at a loss, because its material is ART.

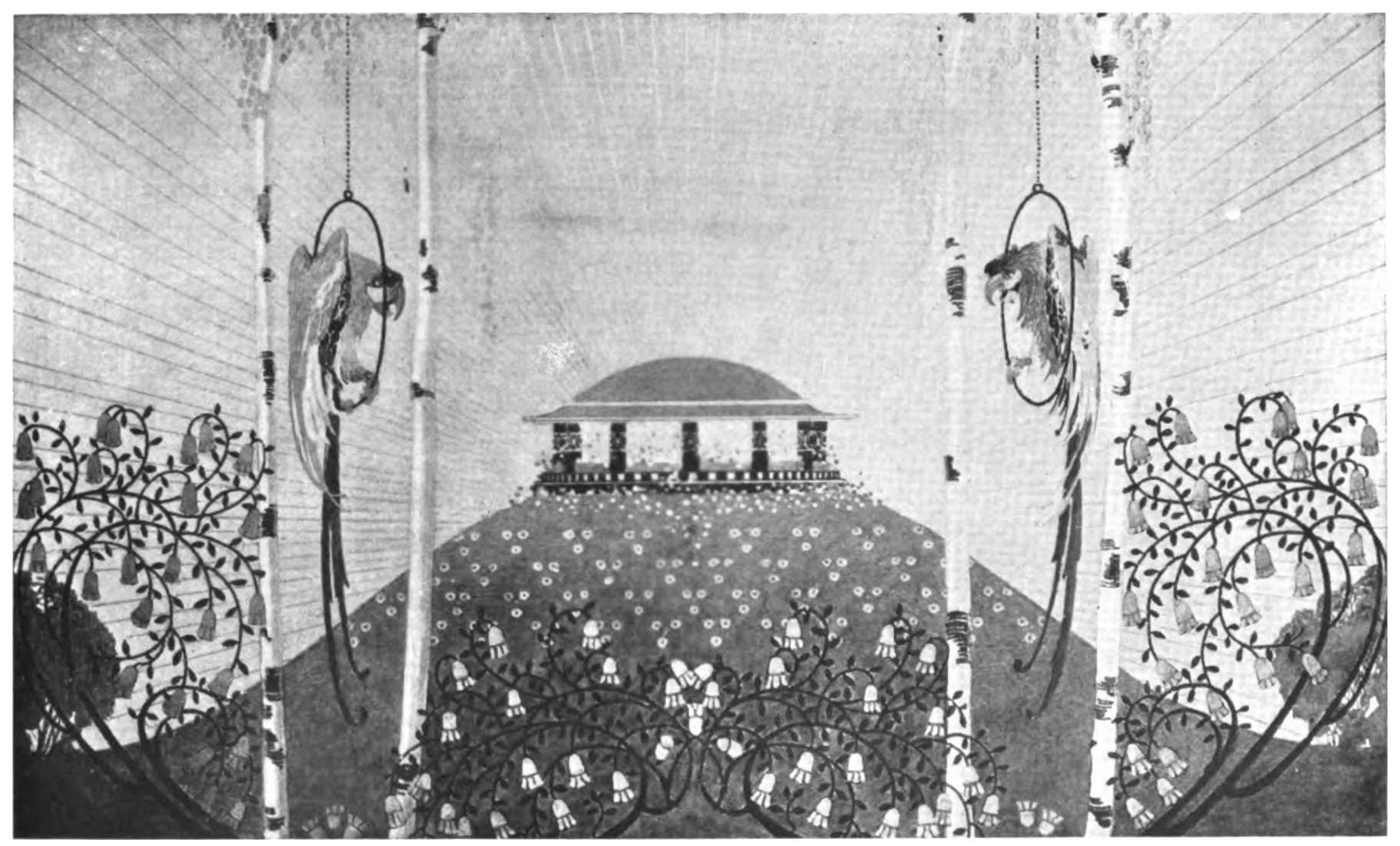

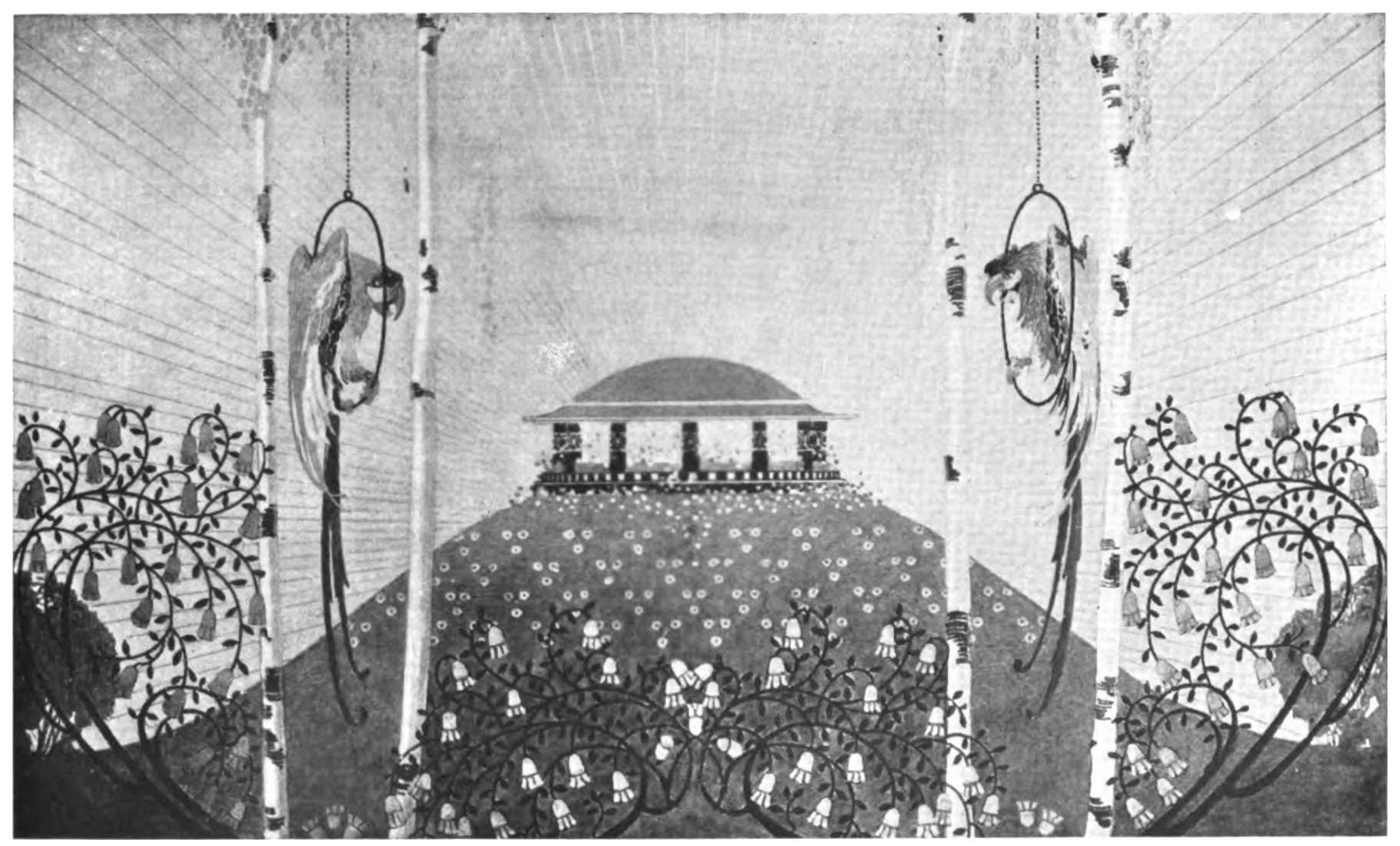

THE SUN’S DWELLING. BY JOSEPH URBAN

The same thing is true in other fields—in producing serious plays, in writing great novels, we will stand for a second-rateness we would not for a moment abide in the construction of a bridge or the making of an omelette, or the production of a revue. And because in a revue the bunk doesn’t carry, the revue is one of the few places you can go with the assurance that the thing, however tawdry in itself, will be well done. If it is tawdry, it is so in keeping with the taste of its patrons, and without pretense; whereas in the major arts—no matter how magnificent the masquerade of Art may be—the taste of a production is usually several notches below the taste of the patrons.

The good revue pleases the eye, the ear, and the pulse; the very good revue does this so well that it pleases the mind. It operates in that equivocal zone where a thing does not have to be funny—it need only sound funny; nor be beautiful if it can for a fleeting moment appear beautiful. It does not have to send them away laughing or even whistling; all it needs to do is to keep the perceptions of the audience fully engaged all the time, and the evaporation of its pleasures will bring the audience back again and again.

The secret I have alluded to is how to create the atmosphere of seeming—and Mr Ziegfeld knows the secret in every detail. In brief, he makes everything appear perfect by a consummate smoothness of production. Undoubtedly ten or fifteen other people help in this—I use Mr Ziegfeld’s name because in the end he is responsible for the kind of show put out in his name and because the smoothness I refer to goes far beyond the mechanism of the stage or skill in directing a chorus. It is not the smoothness of a connecting rod running in oil, but of a batter where all the ingredients are so promptly introduced and so thoroughly integrated that in the end a man may stand up and say, This is a Show. Everyone with a grain of sense knows that Mr Urban can make all the sets for a production and Mr Berlin write all the music; Mr Ziegfeld has the added grain to see that if he’s going to have a great variety of things and people, he had better divide his décor and his music among many different talents.

There have been funnier revues and revues more pleasing to the eye and revues with far better popular music; nowhere have all the necessary ingredients appeared to such a high average of advantage. Mr Anderson could barely keep Bert Savoy within the bounds of a revue; the Music Box collapses entirely as a revue at a few dance steps by Bobby Clark. But Ziegfeld as early as 1910 was able to throw together Harry Watson (Young Kid Battling Dugan, nowadays, in vaudeville), Fannie Brice, Anna Held, Bert Williams, and Lillian Lorraine and, as if to prove that he was none the less producing a revue, bring down his curtain on a set-piece of “Our American Colleges.” And twelve years later, with Will Rogers and Gilda Grey and Victor Herbert and Ring Lardner, he is still producing a revue and brings both curtains down on his chorus—once en masse and the second time undressing for the street in silhouette.

I cannot estimate the amount of satisfaction which since those early days Mr Ziegfeld has provided. My own memories do not go back to the actual productions in which Anna Held figured; I recall only the virtuous indignation of elderly people and my own mixed feelings of curiosity and disgust when I overheard reports of the goings-on. But from the time I begin to remember them until to-day there has always been a peculiar quality of pleasure in the Ziegfeld shows, and the uninterrupted supply of things pleasant to see and entertaining to hear, has been admirable. Mr Ziegfeld has never been actually courageous; his novelties are never more audacious than, say, radiolite costumes or an Urban backdrop. He is apparently pledged to the tedious set-pieces which are supposed to be artistic—the Ben Ali Haggin effects, the Fan in Many Lands or the ballot of A Night in Statuary Hall with the discobolus coming to life and the arms of the Venus de Milo miraculously restored. There are years, too, in which Mr Ziegfeld, discovering new talent, follows but one vein and leaves his shows so much in one tone that a slight depression sets in. Mr Edmund Wilson, in the Dial repeats the plaint of Mr Heywood Broun in the World—that the Follies are frigid—the girls are all straight, the ballet becomes a drill, the very laughs are organized and mechanical. Well, it happens to be the function of the Ziegfeld Follies to be Apollonic, not Dionysian; the leap and the cry of the bacchanale give way to the song and dance, and when we want the true frenzy we have to go elsewhere. I doubt whether even the success of the negro shows will frighten Ziegfeld into mingling with his other elements some that will be riotous and wild; the best they can do will be to prevent Ziegfeld from growing too utterly “refined.” He tends at this moment to quiet fun of the Lardner type and the occasional horseplay with which he accentuates this murmur, this smile, is usually unsuccessful. I am, myself, more moved by broader strokes than his, but I recognize that Ziegfeld, and not the producers of Shuffle Along, is in the main current of our development—that we tend to a mechanically perfect society in which we will either master the machine or be enslaved by it. And the only way to master it—since we cannot escape—will be by understanding it in every detail. That is exactly Mr Ziegfeld’s present preoccupation. I dissent, however, from the suggestion that the physical loveliness of the Ziegfeld chorus has ceased to be seductive. Some, as Mr Lardner once said—some like ’em cold, and there are at least five other choruses which affect me as pleasurably. But for those that like the Ziegfeld-type chorus, which has always a deal of stateliness and a haughty air of being damned well bred, Mr Ziegfeld’s production of the wares is perfect. He has simply moved his chorus one step backward in order to make them appear slightly inaccessible and so a little more desirable. His attack is indirect, but it is no less certain.

In the back of the mind there always remains the idea that a revue ought to be a revue of something, and as far as I know, George M. Cohan is the last of those who have tried to accomplish that. Weber and Fields presented burlesque; Mr Cohan’s efforts are not lost in that dim perspective, and they seem superior, for he wove his amazingly expert parodies of current successes into a new creation, a veritable review. The high spirits and sophistication of the Cohan revues have not frequently been equalled on our stage, for the whole of Cohan’s talents were poured into them without reserve. The parodies and satire were merciless and spared not even himself; for he took the old jibe about his Yankee-Doodleism and wrote apropos of a show of his which had failed: “Go, get a Flag, For you need it, you need it, you know you need it!” He took off Common Clay in swift and expert patter; he destroyed the “song hit” with Down by the Erie ten years earlier and ten times better than the Forty-niners did; he advertised himself and ridiculed his own self-advertisement; he was the principal actor and he played fair with Willie Collier and Charles Winninger and Louise Dresser. Throughout he was the high point of Cohanism, of that shrewd, cock-sure, arrogant, wise, and witty man who was the true expression of the America of Remember the Maine!, the McKinley elections, the Yellow Kid, and Coon! Coon! Coon! He was always smart, always versatile. To this day he is smart enough to produce Mary and Little Nelly Kelly, knowing that the old stuff goes biggest and that even in the midst of his own sophistication he can capture vaster audiences with his own simplicity. This is an abdication of his proper function, to be sure. The man who had so much to do with the great-American-drama (I allude to Seven Keys to Baldpate and the description “great-American” is deliberate) and who could take any trash (A Prince There Was) and make it go, through the indefatigable energy and the cleverness of his own acting, and who could fight the world with his preposterous Tavern—this man had no right to give up doing what he did so well. I care nothing for the famous nasalities of George M. Cohan; after the Four Cohans I saw him first as actor, so I do not mourn for his dancing days. But I know that with only a fraction of Berlin’s gifts as a composer, he had something which even Berlin lacks: the complete sense of the boards. His revues would have been desirable additions to each theatrical season if they had done no more than produce himself. His hard sense, his unimaginative but not unsympathetic response to everything that took place on the street and at the bar and on the stage made him a prince of reviewers—he was not without malice and he was wholly without philosophy. Perhaps that is why his revues were wonderfully gay. Why they ever stopped I cannot tell; when they stopped, strangely enough, they left the field to the Winter Garden. I make no claim that the revues at this house are always pleasing; people apparently still exist who are enthusiasts for Valeska Surratt. But I do claim that they are always revues, even if they are sometimes to be weighed by avoirdupois and not by critical standard.

(Courtesy of A. and C. Boni)

GEORGE M. COHAN. BY ALFRED FRUEH

The annihilation of all the vast and silly posturing which went on a few years ago under the name of The Jest was accomplished in a perfect burlesque by Blanche Ring and Charles Winninger (the latter played Leo Ditrichstein in one of the Cohan revues) and if The Sheik never reached the stage it is possibly because Eddie Cantor burlesqued it in advance on a bicycle and with a time clock for the women of the harem. What has held the Winter Garden down (except, of course, when Al Jolson there inhabited) is the lack of good music; for the humour has always been broad and the slap-stick merry. The shows there always seem to be hankering a little for the additional vulgarity of out-and-out burlesque, but the Rath Brothers were as much at home there as the Avon Comedy Four; if my head were at stake I could not recall a single thing there which could be called exquisite, but I swear that as the show girls shuffled precariously up and down the runway I did at times fancy I heard the stamping of a goatish foot behind the scenes, and if I didn’t like the sound, I was in the minority. The Winter Garden has always been, in part, a direct assault on the senses and the method of art is always indirect; Mr Ziegfeld knows this and always manages to bathe his scenes in a cool virginal light, to the intensification of pleasure for the connoisseurs.

The difference between these two shows can be measured by watching one figure pass across the stage of each. Last year at the Winter Garden Conchita Piquer sang a malagueña. (You can discover all you need to know about the malagueña in Mr Santayana’s Soliloquies; to us it is the perfect exotic, as strange to our ears as Chinese song—stranger because it remains recognizably Occidental, yet seems to be based on no intervals known to our scales, and its rhythm is capricious and uncertain). She sang it “wildly well,” with a pert assured air of superiority. Yet she cast flowers into the audience as she did so, and the background and the massing of the chorus behind her were all out of key and prevented the song from being what at the Ziegfeld Follies it inevitably must have been, exquisite.

At the Follies passes Gilda Grey, a performer of limited talents gifted with unutterable intensity. Against a flaring background in which all the signs of all of Broadway are crowded together, she sings a commentary on the negro invasion—It’s Getting Very Dark on Old Broadway—the scene fades and radiolite picks out the white dresses of the chorus, the hands and faces recede into undistinguishable black. And while the chorus sings Miss Grey’s voice rises in a deep and shuddering ecstasy to cry out the two words, “Getting darker!” To disengage that cry, to insure its repercussion, went all the skill of production in everything that preceded and in everything that followed. It was exciting, but it was also exquisite, and that is exactly what the Winter Garden could not have done.

Neither of the two Music Box revues has reached that height, because in neither has production kept pace with Berlin’s music. It is part of the technique of the revue to have “stunts” and Berlin, being capable du tout, last year set a dining menu to music. Yet nothing was added when lobster and mayonnaise and celery appeared in the flesh; even worse, this year something precious is lost when one of Berlin’s veritable masterpieces, Pack Up Your Sins and Go to the Devil, is produced with an endless number of trapdoors and hoists and all the other mechanics of the stage. The first of the two revues flourished on humour—Willie Collier and Sam Bernard were inexpressibly funny—and on Berlin’s Say It With Music; so long as it stayed in New York the appearance in person of Mr Berlin, explaining to the well-remembered tunes how he wrote each of his masterpieces of ragtime, added much.

The tone of this revue was the tone of the building itself—varying from the cool and well-proportioned exterior to the comfortable, a little lavish interior. Florence Moore was as outrageous as ever, and at least as active; she is the most tireless person on the stage and to me the most tiring, for her vitality affects me as a cyclone in which I am quite unnecessarily involved. All the more surprising, then, was her shift from horseplay to burlesque in the house-hunting scene with Sam Bernard, at the end of which the children were shot by their despairing parents to remove the one obstacle between them and the perfect apartment. In an earlier scene Collier had had his chance—the one in which Bernard tried to explain his difficulties and to read a letter. All of Bernard’s stutterings and flounderings in the English vocabulary availed nothing against Collier’s imperturbable indifference. Collier has always had a divine spark—it was visible even in The Hottentot—and in that scene it glowed beautifully. The show was, to be sure, held in the matrix of Berlin’s score, and was as much held down as up to that level—I mean it was not spoiled by the intrusion of alien theatrical elements. Since then a new hydraulic system has apparently been added to the equipment of the stage, and Hassard Short, confusing the dynamics of the theatre with mere hoisting power, moves everything that can be moved except the audience. The elements are all there, but they are produced as if it were a benefit, not a revue.

(Courtesy of A. and C. Boni)

WILLIE COLLIER. By Alfred Frueh

John Murray Anderson’s is the hardest case to be sure about. A year ago he “struck a new note in revues”—by producing one without a scintilla of interest in any of its proceedings. Nothing quite so lackadaisical and dull has ever had such a success. Yet he had long before established a repute for being artistic—and, as far as I can judge, it was by the exploitation of millions of yards of draperies in place of the usual canvas scenery. It was a sound notion, and in the first of these productions, What’s in a Name? there was a pretty air of the semi-professional, a challenging suggestion of improvisation, as if the chorus and principals weren’t sure from moment to moment what the régisseur might suggest for them to do next.

He has always presented some of the loveliest and some of the ugliest costumes in New York; and now that draperies are no longer his only resource, he falls back upon transformations in scenery, or makes a painted backdrop of the Moonlight Sonata come to life, with music, to the astonishment of the multitude.

In short, it would appear that Mr Anderson is introducing into the revue precisely that element of artistic bunk which has long been the property of the bogus arts. I resent it, and resent it the more because he doesn’t need it. In his recent show there were elements beyond words to praise; the singing of Yvonne George was superb and superbly arranged; the Widow Brown song, sung and danced by Bert Savoy, had a quality of tenderness which all the sentimental songs in the Ziegfeld Follies try vainly to transmit; the two little tumblers, Fortunello and Cirillino, are by name and manner of the commedia dell’arte and John Hazzard’s song about Alaska, with slides by Walter Hoban, is the stuff that Forty-niners are made of.

It was in this show that the Herriman-Carpenter ballet of Krazy Kat was tried and dismissed, and the fault here is the fault of Mr Anderson throughout. Again it was attempted with an artistic dancer, when everyone who has intelligence of Krazy knows that it should be done by an American stunt dancer until the time when Mr Chaplin finds time to do it. Krazy Kat is exquisite and funny—and whether Mr Carpenter lets him remain so or not, it is clear that Mr Anderson wanted him to be artistic at all cost. So with his whole production; he has sacrificed fun all the way down the line; one is pleased, much more than amused, and the gigantic revelry, the broad levity of Bert Savoy stand apart from the show like a stranger. It is the one revue in which the mass dancing entirely fails to remain in the memory, and I am convinced that if Miss Brice hadn’t, in the Ziegfeld Follies, made Mon Homme a popular hit, Miss George’s far more fiery and varied and more generally interesting rendition of it would leave it cold in the ears of the audiences. For Mr Anderson has so far learned only to put over separate things, and until you put the whole thing over the individual things gain but half their victories.

That completes the circle to Mr Ziegfeld, and, since it is a question of putting it over, associates with him another man who on at least one occasion has done as well, Mr Charles Dillingham. If you omit the one man shows as practised by Ed Wynn, Frank Tinney and Al Jolson, and the nondescripts of Hitchcock, and pass over Stop! Look! Listen! as varying too far from the revue type, there remains Watch Your Step as another high spot in production, with the dancing of the Castles, the humours of that very great comedian, Harry Kelly, and of Tinney, the scenery and costumes by Robert McQuinn and Helen Dryden, and the whole story of contemporary dancing in Mr Berlin’s music. Except for Harry Kelly, every item was bettered in Stop! Look! Listen!, but in spite of the presence of Gaby Deslys, it was not a revue—whereas Watch Your Step almost consciously set out to proclaim itself superior in fineness and slickness to the Follies and almost succeeded.

I am trying to sketch the main types of revue, not to write a history of the revue; it is to be hoped that some one sufficiently sentimental can be found to do the job. Whether in a history the drunken scene of Leon Errol in the subway would figure largely, I do not know; I am not even sure that the scene in the Grand Central while it was building, with Bert Williams as the porter, would be noted; quite possibly the memory of Lillian Lorraine on the swings—to me merely a bearable necessity—and Frank Carter singing, (1918) I’m Going to Pin My Medal on the Girl I Left Behind, will seem more important than Ina Claire’s mimicry of Frances Starr’s Marie-Odile. It is possible that the injection of real humour, like Lardner’s, may make the set scenes like Laceland or the History of Shoes through the Ages or Our Colleges more and more dispensable. I do not know. I feel fairly certain only of this: that the relative importance of the workers in the field is measured by their mastery of the art of production far more than by their skill in picking individuals and stunts. I am also convinced that those who have arrived at this perfection in an effort to give America pleasure have done more for us than those who haven’t got half way in trying to give us art.