THE ONE-MAN SHOW

WHEN all the other grave æsthetic questions about the stage are answered, some profound theorist may explain the existence of the one-man show. Since I am not a materialist, I cannot concede the obvious solution—that a man finds enough money to produce himself in a Broadway show—because there is something attractive and mysterious about this type of entertainment which the explanation fails to explain.

The theory of the one-man show is apparently that there are individuals so endowed, so versatile, and so beloved, that no other vehicle will suffice to let them do their work. Conversely, that they are of such quality that they suffice for the strange entertainment with which they are surrounded and that nothing else matters provided they are long and frequent on the stage. Six men and two women are in the first roster of the one-man show: Fred Stone, Ed Wynn, Raymond Hitchcock, Eddie Cantor, Frank Tinney, and Al Jolson; below them, leading the women, Elsie Janis and Nora Bayes. And omitting Jolson because he is so great that he cannot be put in any company, the greatest one-man show was one in which none of these appeared—it was one in which even the man himself didn’t appear. It was a show in which one man succeeded where all of these, this time not excluding Jolson, had failed: for he made the whole production his kind of show—and the others have never quite managed to do more than make themselves.

The chief example of this failure is Hitchcock, whose series lapses ever so often, leaving him stranded on the bleak shore of a Pin Wheel Revue—an artistic, an intellectual, an incredibly stupid production which Hitchy manfully tried first to save and then to abandon. There were in the better Hitchy shows other first-rate people: one who masqueraded as Joseph Cook and was none other than Joe Cook the Humorist out of vaudeville and out of his element; Ray Dooley was with Hitchy, I believe, and there were always good dancers. Hitchy kept on the stage a long time, as conférencier and as participant, and his amiable drollery was always at the same level—just enough. He never quite concealed the strain of making a production go; one always wanted to be much more amused, and Hitchy never got beyond the episode of the Captain of the Fire Brigade or trying to buy the middle two-cent stamp in a sheet of a hundred. A series of vaudeville sketches doesn’t make a one-man show, even if he plays in all of them; and the moment Hitchcock was off, Hitchy-koo went to pieces, some good and some bad, and all trying a little too hard to be something else.

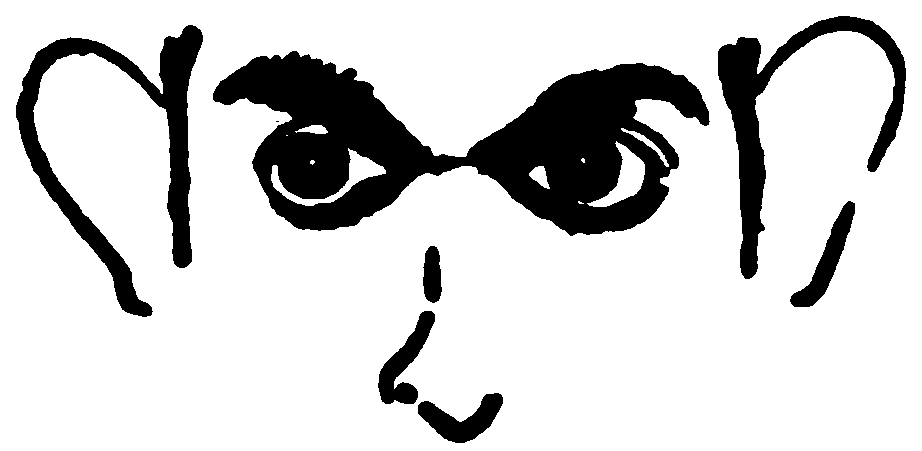

EDDIE CANTOR

By Roland Young

Eddie Cantor and Al Jolson appear in the two different Winter Garden types of show—the Jolson and the Winter Garden in impuris naturalibus. Jolson infuses something both gay and broad into his pieces; even the recurrence of Lawrence D’Orsay cannot win back the original Winter Garden atmosphere and even the disappearance of Kitty Doner cannot diminish Jolson’s private quality. Of the straight Winter Garden shows, the 1922 with Eddie Cantor was the best in ten years, made so by Cantor and made by him, in spite of the billing, into a one-man show. The nervous energy of Cantor isn’t sufficient to animate the active, but indifferent choruses of the Shuberts. One thing, however, he can do superbly—the lamb led to the slaughter. It is best when he chooses to play the timid, Ghetto-bred, pale-faced Jewish lad, seduced by glory or the prospects of pay into competing with athletes and bruisers. One thing he cannot do and should learn not to try—the black-face song and comedy of his master, Jolson. The scenes of violence vary; that of the osteopath was an exploitation of meaningless brutality; I cared for nothing after Eddie’s frightened entrance, “Are you the Ostermoor?” But the aviation examination and the application for the police force were excellent pieces of construction, holding sympathy all the way through and keeping on the safe side of nausea. Both of these were before the Winter Garden days and the Winter Garden exploit was better than either. He played here a cutter in a hand-me-down clothing store and it was his function to leap into the breach whenever a customer showed the slightest tendency to leave without buying a suit. The victim was obsessed by some idea of having “a belt in the back” and was forced into sailor suits and fancy costume and was generally made miserable. Eddie’s terrific rushes from the wings, his appeals to God to strike him dead “on the spot” if the suit now being tried on wasn’t the best suit in the world, his helplessness and his, “Well, kill me, so kill me,” as apology when his partner revealed the damning fact that that happened to be the man’s old suit—all of this was worth the whole of the Potash-Perlmutter cycle. And the whole-heartedness of Cantor’s violence—essentially the bullying of a coward who has at last discovered some one weaker than himself, was faultless. He sings well the slightly suggestive songs like After the Ball (new version), and his three broken dance steps with the sawing motion of his gloved hands create an image exceedingly precise and palpable. There is in him just enough for the one-man show, but so far it has been limited by his tendency to imitate and by failure to develop his own sources of strength. Even in Kid Boots he just fails to make the grade.

FRANK TINNEY

By Roland Young

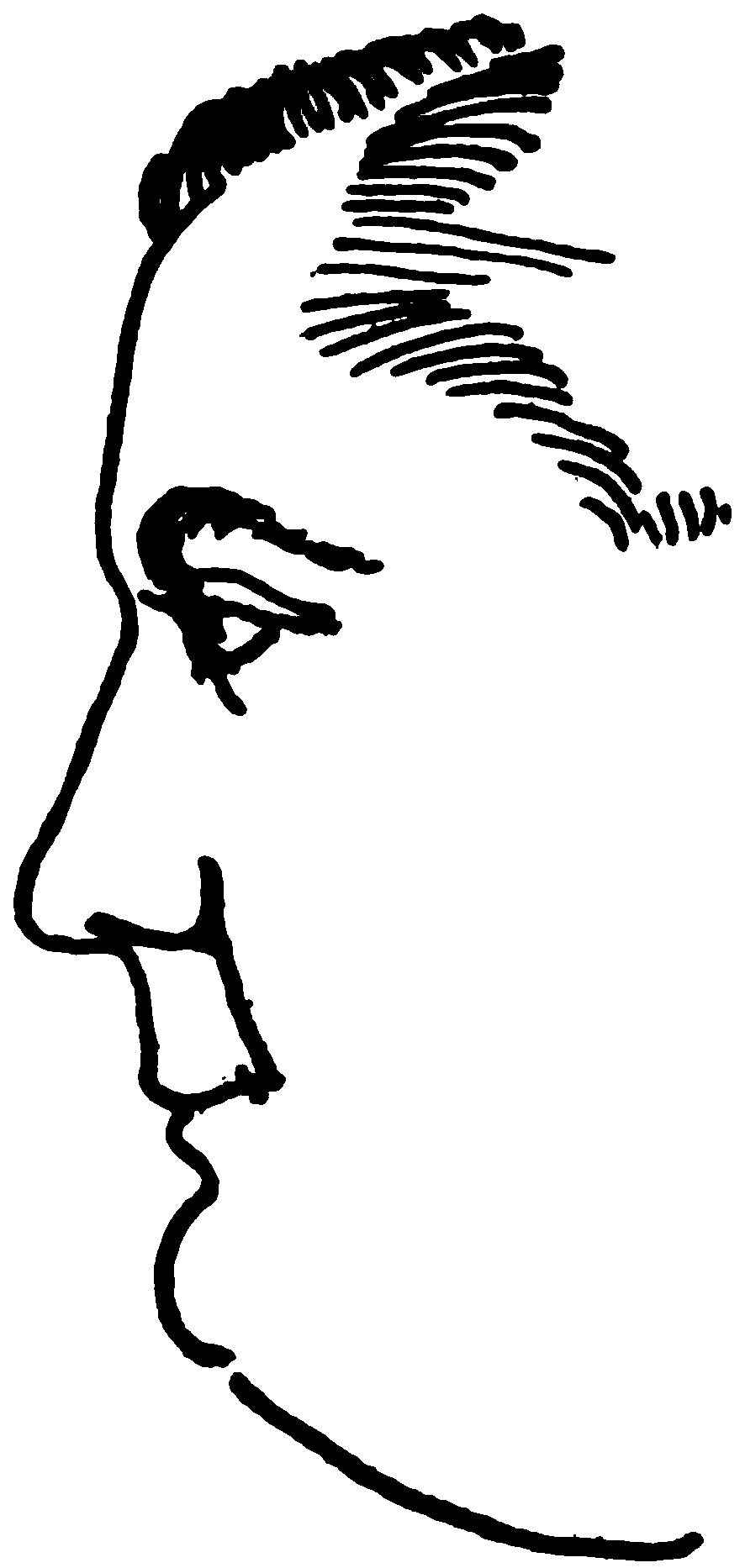

The one-man show requires its leader to leave nothing in himself unexploited—there is too much for him to do and he must take everything on himself—the requirements are exactly opposite to those of the vaudeville act where the actor must work in the briefest compass, with the utmost concentration, and get his effects in the shortest time. Frank Tinney’s success in vaudeville marks the limitations of his success in his shows—for he imposed on vaudeville that languid easy-going manner of his and was just enough out of vaudeville tempo (he is very deceptive in this) to appear to be a novelty there. In essence he isn’t a good one-man, for his line is limited and his humour and his good-humour (in which he is matched only by Ed Wynn) are not capable of the strain of a long winter’s evening entertainment. Tinney was excellent in a quarrel scene with Bernard Granville (in a Ziegfeld Follies, I think) the two pacing in opposite directions, the width of the stage between them, always from footlights to backdrop and never crossing the stage; he was disputatious and entertaining on the negative of the proposition that the Erie railroad (pronounced for reasons of his own, Ee-righ) is a very expensive railroad; his appearance in Watch Your Step was almost perfect. (Consult Mr A. Woollcott’s Shouts and Murmurs for everything about Tinney; Mr Woollcott’s descriptions are accurate and evocative and he errs only in his estimate of Tinney’s quality.) Tinney has everything except the excess of vitality, the surcharge of genius. He has method nearly to perfection and it is a wholly original, ingratiating, and, up to a certain point, adaptable method. What he has done is to destroy the “good joke,” for all of Tinney’s jokes are bad ones and he gets his effect by fumbling about with them, by lengthening the preliminaries, by false starts, erasures, corrections—until his arrival at the point relieves the suspense. I have heard him take at least ten minutes to put over: “Lend me a dollar for a week, old man.—Who is the weak old man?” and not a moment was superfluous. He is expert at kidding the audience, and as he is never in character he never steps out. There isn’t quite enough of him, that is all.

There is enough of Fred Stone for versatility and not enough for specific personal appeal. As acrobat, dancer, ventriloquist, and cut-up Stone is easily in the lead; but the unnamable quality is lacking. See him climbing up an arbour to meet his Juliet in the balcony; he is discovered, hangs head downward in peril of his life, seizes a potted flower and with it begins to dust the vines—it is Chaplinesque in conception and beautifully executed. See him on the slack rope continually on the point of falling off and continually recovering and seeming to hang on by his boot toe; or in The Lady of the Slipper making a beautiful series of leaps from chair to divan, from divan to table, to a triumphant exit through the unsuspected scenery; or in another quality recall the famous “Very good, Eddie,” of Chin-Chin. He is incredible; one wouldn’t miss him for worlds; yet it is always what he does and not himself that constitutes the attraction. I wonder whether I do not wrong him altogether by classing him with the one-men, for it was always something more than Montgomery and Stone in the days of The Red Mill and Stone does not exaggerate himself on the stage. His command of attributes is greater than that of any other player; he does everything with a beautiful, errorless accuracy—and the pleasure of seeing things exactly right, all the time, is not to be underestimated.

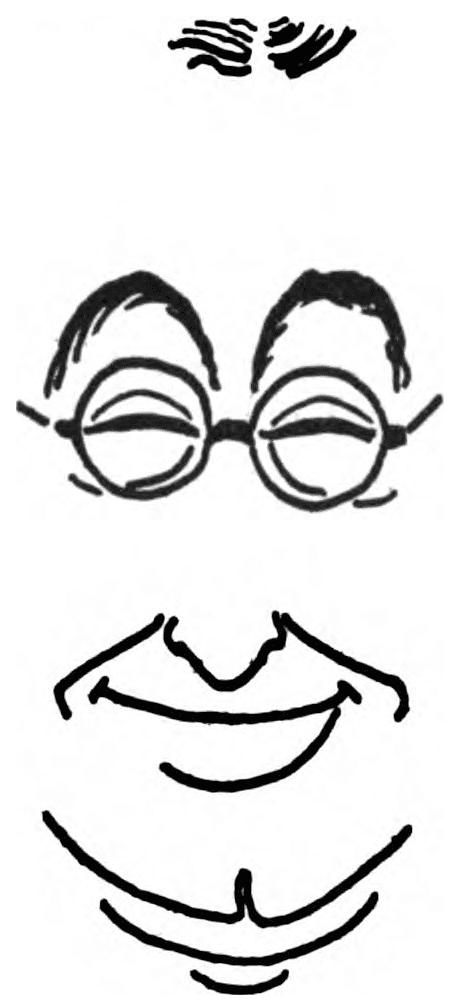

ED. WYNN|

By Roland Young

It is Ed Wynn’s pleasure to make everything seem utterly haphazard. Wynn is a surd in the theatre—there is always something left unresolved in reducing him to the lowest term, and he is incommensurable because there are no standards for him and no similars. I prefer to see him wandering through a good revue, changing hats, worrying about a “rewolwer” in the first scene and stopping dead in the twentieth to declare that it wasn’t a “rewolwer” at all, but a pistol. When he came to put on a one-man show he preserved the best part of this incoherence. He made it his business to appear before a drop curtain and explain in an amazing vocabulary and with painstaking gravity exactly what was to occur in the next scene. He affects to be awkward (to quote him, I might go so far as to call him uncouth.... I think I will call him uncouth.... He is uncouth); his gestures are florid and wide, his earnestness makes all things vivid. Each of these explanations involves a bad pun and none, of course, has anything to do with the scene that actually follows. Like Jolson and Cantor, he takes the stage at a given moment and entertains. His famous inventions seemed to be the crudest form of humour—a typewriter carriage for eating corn on the cob, a burning candle to set in one’s ears in order to wake up in time—yet sheer ebullition carried them high into the field of “nice, clean fun.” Wynn’s words come tumbling out of him, agglutinated, chaotic, disorderly; he is abashed by his own occasional temerity, he is timid and covers it with brashness—and all of this is a carefully created personage; it is not Ed Wynn. He has found a little odd corner of life which no one else cultivates; it is a sort of rusticity in the face of simple things; he is a perpetual immigrant obsessed by hats and shoes and words and small ideas, instead of bothering about skyscrapers. The deepness of his zanylike appreciation of every-day things is the secret of his capacity for making them startling and funny. His one fault is the show with which he surrounds himself.

I have never seen Elsie Janis better than she was in The Lady of the Slipper—with the exception of Gaby Deslys I have never seen any woman comparable to Miss Janis in that piece, and in it she had qualities which ought to have made her appearance in an individual show a much greater success than it actually turned out to be. For, except a voice, Miss Janis has everything. She is a beautiful dancer and her legs are handsomer than Mistinguett’s, and she is the finest mimic I have ever seen on the stage, several shades ahead of Ina Claire. An exceptional intelligence operates in the creation of these caricatures, for they are all created by seizing upon vital characteristics of tone, gesture, tempo of movement, spirit; and the arrangement of her hair and the contortions of her face are only guide-signs to the accomplished act. She is herself of an abounding grace, a suppleness of body and of mind, and the measure of her skill is the exact degree in which her grace and simplicity are transformed into harshness or angularity or sophistication as she passes one after another of our stage personalities before her mirror. This year I saw her in a Paris music-hall take off Mistinguett and Max Dearly. She presented them singing Give Me Moonlight in their own imagined versions and her throaty “Give me a gas light” for the creator of Mon Homme was superb. She offered to sing it, at the end, as she herself ought to sing it—and danced it without uttering a sound. It reminded one of Irene Castle in Watch Your Step. For an exact calculation of her capacities and a sensible, modest intention to stay within them and to exploit them to the limit are parts of Elsie Janis’s intelligence. To be sure, it isn’t her intelligence—it is her loveliness and her talent that endear her to us. But it is grateful, for once in a way, to find a talent so great, a loveliness so irresistible, joined to an intelligence which sets all in motion and spoils nothing.

I suspect that in spite of the best of the one-man shows there is something wrong with the idea—perhaps because the environment requires more than any man has yet been able to give. And the one perfect example is, as I have suggested, proof of this. Because Stop! Look! Listen! which was only a moderate success on Broadway and involved the talents of Gaby Deslys, Doyle and Dixon, Harry Fox, Tempest and Sunshine, the beautiful Justine Johnston, Helen Barnes, Helen Dryden as costumer and Robert McQuinn as scenic designer, a beautiful chorus and an excellent producer, was actually the one-man show of Irving Berlin. For once a complete and varied show expressed the spirit of one man to perfection. In that piece, Berlin wrote two of his masterpieces and about four other superb songs; and, more than that, suffused the entire production with the gay spirit of his music. There occurred The Ragtime Melodrama danced by Doyle and Dixon—only the Common Clay scene from the Cohan revue ever approached it, and Doyle and Dixon never danced better (unless, possibly, a quarter of an hour earlier in The Hula-Hula); there was The Girl on the Magazine Cover, perfectly set and costumed, a really good sentimental song with its quaint introduction of Lohengrin (not the Wedding March); there was When I Get Back to the U. S. A. sung against a chorus of My Country, ’Tis of Thee; there was Gaby’s wicked Take Off a Little Bit and Harry Fox’s Press-Agent Song—and finally the second of Berlin’s three great tributes to his art: I Love a Piano, which, like the mother of Louis Napoleon, he wrote for six pianos and in which everything in syncopation up to that time was epitomized and carried to a perfect conclusion. Whatever was gay, light, colourful, whatever was accurate, assured, confident, and good-humoured, was in this miraculous production. I saw it twelve times in two weeks—lured partly, I must confess, by the hope that Harry Pilcer would break at least a leg in his fall down the golden stairs. He never did; in spite of which, seeing it again, months later, it still seemed to me the apotheosis of pure show. I think I could reconstruct every moment of it, including the useless plot and Justine Johnston’s ankles; it seems a pity that all of it, the ephemeral and the permanent, should have already passed from the stage. It was a beginning in ragtime operetta which Mr Berlin has never followed up; his inexhaustible talents have been diverted into other things; he is now a maker of revues. Yet when he saw The Beggar’s Opera, Mr Berlin felt something plucking at his sleeve, reminding him that it was his job, and his alone, to create the comparable type for America.

At that moment he thought back to Stop! Look! Listen!—but he had already begun to build the Music Box—and we must wait patiently for what time will bring as a real successor to his one-man show. At any rate, we have had it. We know, now, what it can amount to—and it is enough. Enough, at any rate, to put the veritable one-man show fairly definitely out of the running.