THE DÆMONIC IN THE AMERICAN THEATRE

ONE man on the American stage, and one woman, are possessed—Al Jolson and Fanny Brice. Their dæmons are not of the same order, but together they represent all we have of the Great God Pan, and we ought to be grateful for it. For in addition to being more or less a Christian country, America is a Protestant community and a business organization—and none of these units is peculiarly prolific in the creation of dæmonic individuals. We can bring forth Roosevelts—dynamic creatures, to be sure; but the fury and the exultation of Jolson is a hundred times higher in voltage than that of Roosevelt; we can produce courageous and adventurous women who shoot lions or manage construction gangs and remain pale beside the extraordinary “cutting loose” of Fanny Brice.

To say that each of these two is possessed by a dæmon is a mediæval and perfectly sound way of expressing their intensity of action. It does not prove anything—not even that they are geniuses of a fairly high rank, which in my opinion they are. I use the word possessed because it connotes a quality lacking elsewhere on the stage, and to be found only at moments in other aspects of American life—in religious mania, in good jazz bands, in a rare outbreak of mob violence. The particular intensity I mean is exactly what you do not see at a baseball game, but may at a prize fight, nor in the productions of David Belasco, nor at a political convention; you may see it on the Stock Exchange and you can see it, canalized and disciplined, but still intense, in our skyscraper architecture. It was visible at moments in the old Russian Ballet.

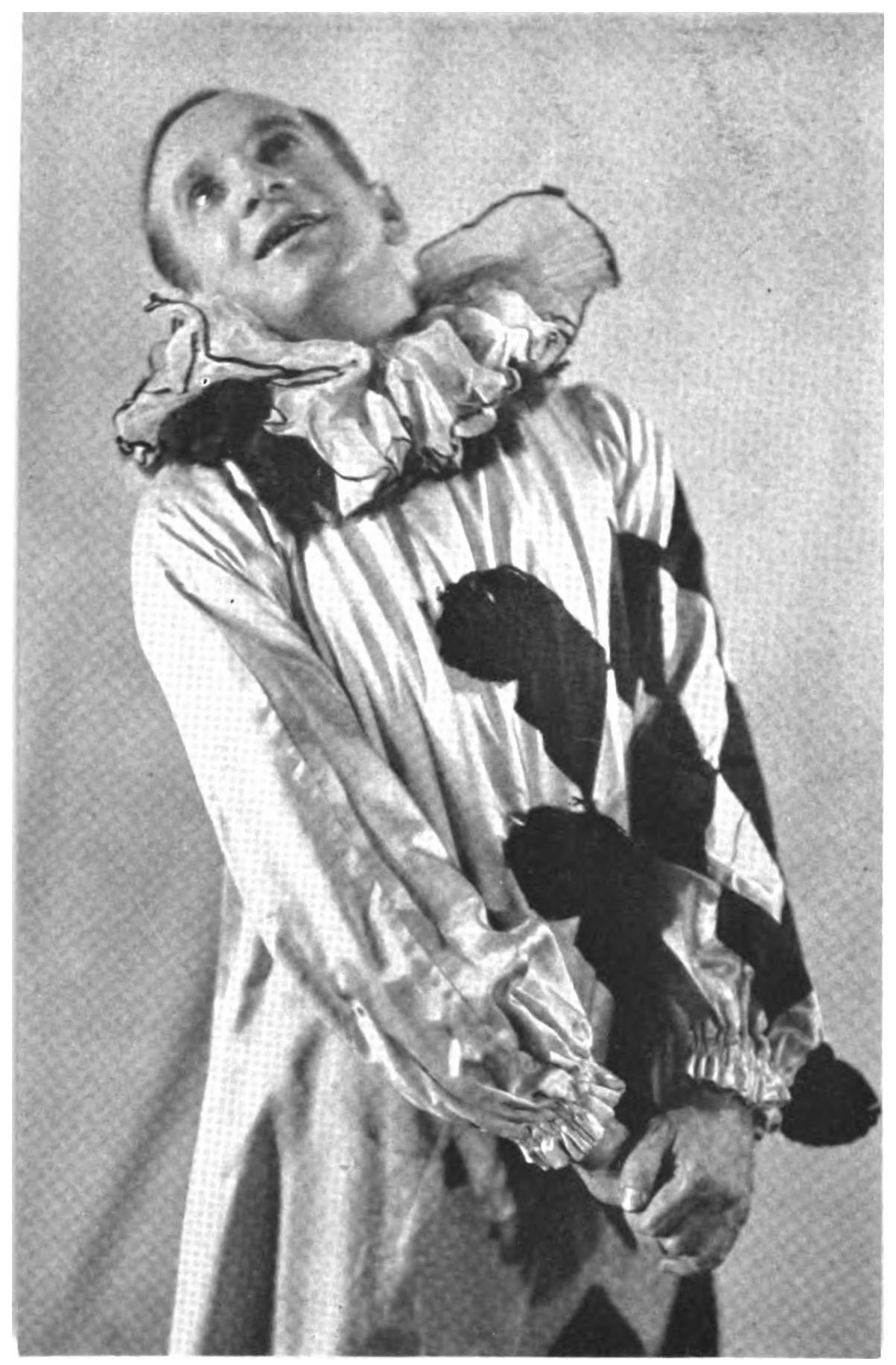

In Jolson there is always one thing you can be sure of: that whatever he does he does at the highest possible pressure. I do not mean that one gets the sense of his effort, for his work is at times the easiest seeming, the most effortless in the world. Only he never saves up—for the next scene, or the next week, or the next show. His generosity is extravagant; he flings into a comic song or three-minute impersonation so much energy, violence, so much of the totality of one human being, that you feel it would suffice for a hundred others. In the days when the runway was planked down the centre of every good theatre in America, this galvanic little figure, leaping and shouting—yet always essentially dancing and singing—upon it was the concentration of our national health and gaiety. In Row, Row, Row he would bounce up on the runway, propel himself by imaginary oars over the heads of the audience, draw equally imaginary slivers from the seat of his trousers, and infuse into the song something wild and roaring and insanely funny. The very phonograph record of his famous Toreador song is full of vitality. Even in later days when the programme announces simply “Al Jolson” (about 10.15 P.M. in each of his reviews) he appears and sings and talks to the audience and dances off—and when he has done more than any other ten men, he returns and, blandly announcing that “You ain’t heard nothing yet,” proceeds to do twice as much again. He is the great master of the one-man show because he gives so much while he is on that the audience remains content while he is off—and his electrical energy almost always develops activity in those about him.

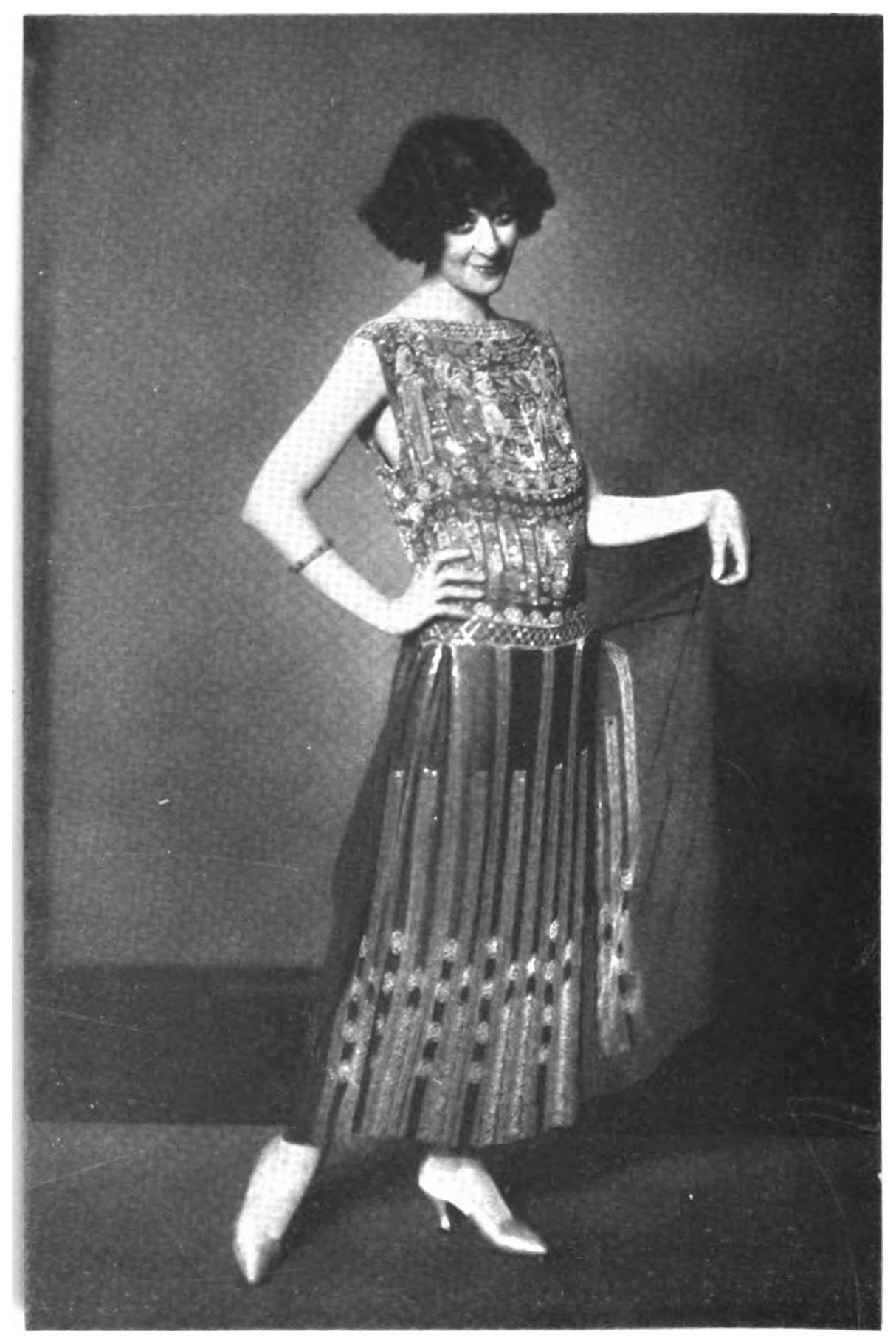

FANNY BRICE

If it were necessary, a plea could be made for violence per se in the American theatre, because everything tends to prettify and restrain, and the energy of the theatre is dying out. But Jolson, who lacks discipline almost entirely, has other qualities besides violence. He has an excellent baritone voice, a good ear for dialect, a nimble presence, and a distinct sense of character. Of course it would be impossible not to recognize him the moment he appears on the stage; of course he is always Jolson—but he is also always Gus and always Inbad the Porter, and always Bombo. He has created a way of being for the characters he takes on; they live specifically in the mad world of the Jolson show; their wit and their bathos are singularly creditable characteristics of themselves—not of Jolson. You may recall a scene—I think the show was called Dancing Around—in which a lady knocks at the door of a house. From within comes the voice of Jolson singing, “You made me love you, I didn’t wanna do it, I didn’t wanna do it”—the voice approaches, dwindles away, resumes—it is a swift characterization of the lazy servant coming to open the door and ready to insult callers, since the master is out. Suddenly the black face leaps through the doorway and cries out, “We don’ want no ice,” and is gone. Or Jolson as the black slave of Columbus, reproached by his master for a long absence. His lips begin to quiver, his chin to tremble; the tears are approaching, when his human independence softly asserts itself and he wails, “We all have our moments.” It is quite true, for Jolson’s technique is the exploitation of these moments; he has himself said that he is the greatest master of hokum in the business, and in the theatre the art of hokum is to make each second count for itself, to save any moment from dulness by the happy intervention of a slap on the back, or by jumping out of character and back again, or any other trick. For there is no question of legitimacy here—everything is right if it makes ’em laugh.

He does more than make ’em laugh; he gives them what I am convinced is a genuine emotional effect ranging from the thrill to the shock. I remember coming home after eighteen months in Europe, during the war, and stepping from the boat to one of the first nights of Sinbad. The spectacle of Jolson’s vitality had the same quality as the impression I got from the New York sky line—one had forgotten that there still existed in the world a force so boundless, an exaltation so high, and that anyone could still storm Heaven with laughter and cheers. He sang on that occasion ’N Everything and Swanee. I have suggested elsewhere that hearing him sing Swanee is what book reviewers and young girls loosely call an experience. I know what Jolson does with false sentiment; here he was dealing with something which by the grace of George Gershwin came true, and there was no necessity for putting anything over. In the absurd black-face which is so little negroid that it goes well with diversions in Yiddish accents, Jolson created image after image of longing, and his existence through the song was wholly in its rhythm. Five years later I heard Jolson in a second-rate show, before an audience listless or hostile, sing this outdated and forgotten song, and create again, for each of us seated before him, the same image—and saw also the tremendous leap in vitality and happiness which took possession of the audience as he sang it. It was marvelous. In the first weeks of Sinbad he sang the words of ’N Everything as they are printed. Gradually (I saw the show in many phases) he interpolated, improvised, always with his absolute sense of rhythmic effect; until at the end it was a series of amorous cries and shouts of triumph to Eros. I have heard him sing also the absurd song about “It isn’t raining rain, It’s raining violets” and remarked him modulating that from sentimentality into a conscious bathos, with his gloved fingers flittering together and his voice rising to absurd fortissimi and the general air of kidding the piece.

He does not generally kid his Mammy songs—as why should he who sings them better than anyone else? He cannot underplay anything, he lacks restraint, and he leans on the second-rate sentiment of these songs until they are forced to render up the little that is real in them. I dislike them and dislike his doing them—as I dislike Belle Baker singing Elie, Elie! But it is quite possible that my discomfort at these exhibitions is proof of their quality. They and a few very cheap jokes and a few sly remarks about sexual perversions are Jolson’s only faults. They are few. For a man who has, year after year, established an intimate relation with no less than a million people, every twelvemonth, he is singularly uncorrupted. That relation is the thing which sets him so far above all the other one-man-show stars. Eddie Cantor gives at times the effect of being as energetic; Wynn is always and Tinney sometimes funnier. But no one else, except Miss Brice, so holds an audience in the hollow of the hand. The hand is steady; the audience never moves. And on the great nights when everything is right, Jolson is driven by a power beyond himself. One sees that he knows what he is doing, but one sees that he doesn’t half realize the power and intensity with which he is doing it. In those moments I cannot help thinking of him as a genius.

Quite to that point Fanny Brice hasn’t reached. She hasn’t, to begin with, the physical vitality of Jolson. But she has a more delicate mind and a richer humour—qualities which generally destroy vitality altogether, and which only enrich hers. She is first a great farceur; and in her songs she is exactly in the tradition of Yvette Guilbert, without the range, so far as we know, which enabled Mme Guilbert to create the whole of mediæval France for us in ten lines of a song. The quality, however, is the same, and Fanny’s evocations are as vivid and as poignant as Yvette’s—they require from us exactly the same tribute of admiration. She has grown in power since she sang and made immortal, I Should Worry. Hear her now creating the tragedy of Second-Hand Rose or of the one Florodora Baby who—“five little dumbells got married for money, And I got married for love....” These things are done with two-thirds of Yvette Guilbert’s material missing, for there are no accessories and, although the words (some of the best are by Blanche Merrill) are good, the music isn’t always distinguished. And the effects are irreproachable. Give Fanny a song she can get her teeth into, Mon Homme, and the result is less certain, but not less interesting. This was one of a series of realistic songs for Mistinguett, who sang it very much as Yvonne George did when she appeared in America. Miss Brice took it lento affetuoso; since the precise character of the song had changed a bit from its rather more outspoken French original. Miss Brice suppressed Fanny altogether in this song—she was being, I fear, “a serious artist”; but she is of such an extraordinary talent that she can do even this. Yvonne George sang it better simply because the figure she evoked as Mon Homme was exactly the fake apache about whom it was written, and not the “my feller” who lurked behind Miss Brice. It was amusing to learn that without a Yiddish accent and without those immense rushes of drollery, without the enormous gawkishness of her other impersonations, Miss Brice could put a song over. But I am for Fanny against Miss Brice and to Fanny I return.

Fanny is one of the few people who “make fun.” She creates that peculiar quality of entertainment which is wholly light-hearted and everything else is added unto her. Of this special quality nothing can be said; one either sees it or doesn’t, savours it or not. Fanny arrives on the scene with an indescribable gesture—after seeing it twenty times I believe that it consists of a feminine salute, touching the forehead and then flinging out her arm to the topmost gallery. There is magic in it, establishing her character at once—the magic must reside in her incredible elbow. She hasn’t so much to give as Jolson, but she gives it with the same generosity, there are no reserves, and it is all for fun. Her Yiddish Squow (how else can I spell that amazing effect?) and her Heiland Lassie are examples—there isn’t an arrière-pensée in them. “The Chiff is after me ... he says I appil to him ... he likes my type ...” it is the complete give away of herself and she doesn’t care.

AL JOLSON

And this carelessness goes through her other exceptional qualities of caricature and satire. For the first there is the famous Vamp, in which she plays the crucial scene of all the vampire stories, preluding it with the first four lines of the poem Mr Kipling failed to throw into the wastepaper basket, and fatuously adding, “I can’t get over it”—after which point everything is flung into another plane—the hollow laughter, the haughty gesture, the pretended compassion, that famous defense of the vampire which here, however, ends with the magnificent line, “I may be a bad woman, but I’m awful good company.” In this brief episode she does three things at once: recites a parody, imitates the moving-picture vamp, and creates through these another, truly comic character. For satire it is Fanny’s special quality that with the utmost economy of means she always creates the original in the very process of destroying it, as in two numbers which are exquisite, her present opening song in vaudeville with its reiterations of Victor Herbert’s Kiss Me Again, and her Spring Dance. The first is pressed far into burlesque, but before she gets there it has fatally destroyed the whole tedious business of polite and sentimental concert-room vocalism; and the second (Fanny in ballet, with her amazingly angular parody of five-position dancing) puts an end forever to that great obsession of ours, classical interpretative dancing.

Fanny’s refinement of technique is far beyond Jolson’s; her effects are broad enough, but her methods are all delicate. The frenzy which takes hold of her is as real as his. With him she has the supreme pleasure of knowing that she can do no wrong—and her spirits mount and intensify with every moment on the stage. She creates rapidly and her characterizations have an exceptional roundness and fulness; when the dæmon attends she is superb.

It is noteworthy that these two stars bring something to America which America lacks and loves—they are, I suppose, two of our most popular entertainers—and that both are racially out of the dominant caste. Possibly this accounts for their fine carelessness about our superstitions of politeness and gentility. The medium in which they work requires more decency and less frankness than usually exist in our private lives; but within these bounds Jolson and Brice go farther, go with more contempt for artificial notions of propriety, than anyone else. Jolson has re-created an ancient type, the scalawag servant with his surface dulness and hidden cleverness, a creation as real as Sganarelle. And Fanny has torn through all the conventions and cried out that gaiety still exists. They are parallel lines surcharged with vital energy. I should like to see that fourth-dimensional show in which they will meet.