THESE, TOO ...

REMY DE GOURMONT has propounded, somewhere, an interesting theory. If life is worth anything per se, is the substance of the argument, then we do wrong to live it in a series of high moments separated by long hours of dulness. We ought to take the amount of energy, or ecstasy, we possess, and spread it as thin as possible, relishing each moment for itself, each being as good as any other. (I do not mean that Gourmont endorsed this philosophy; he discussed it.) It is, of course, the logical conclusion of burning always with a hard gemlike flame, for if one is to be always anything it is more likely to be calm and languorous and reserved; that is the difference between burning and burning up—of which Pater was aware.

We have all had these days of halcyon perfection, when the precise degree of warmth was a miracle, when the aroma of a wine seemed to have the whole fragrance of the earth, when one could do anything or nothing and be equally content. In the presence of great works of art we experience something similar. We are suspended between the sense of release from life, the desire to die before the image of the supremely beautiful, and a new-found capacity for living. Our daily existence gives us no such opportunity; we cannot live languorously because we have no leisure, and we are compelled to be intense at rare intervals if life isn’t to be entirely a hoax and a bore. In the preoccupations of daily life a tragic incident or an outburst of temper or a perfectly cut street dress or the dark-light before a storm, may give us, apart from our emotional lives, the intensity we require. We rather defend ourselves from the impact of great beauty, of nobility, of high tragedy, because we feel ourselves incompetent to master them; we preserve our individual lives even if we diminish them.

The minor arts are, to an extent, an opiate—or rather they trick our hunger for a moment and we are able to sleep. They do not wholly satisfy, but they do not corrupt. And they, too, have their moments of intensity. Our experience of perfection is so limited that even when it occurs in a secondary field we hail its coming. Yet the minor arts are all transient, and these moments have no lasting record, and their creators are unrewarded even by the tribute of a word. A moment comes when everything is exactly right, and you have an occurrence—it may be something exquisite or something unnamably gross; there is in it an ecstasy which sets it apart from everything else. The scene of the “swaree” in the Pickwick Papers has that quality; nearly the whole of South Wind has it (I choose examples as disparate as possible). The whole performance of Boris by Chaliapin (the second time he sang it at the Metropolitan on his second visit to the United States) had precisely the same exaltation—and Conrad Veidt as Cesare had one comparable moment: the breathless second when the draperies seem to cling to the ravished virgin in the hands of the Somnambulist. It is an unpredictable event; but there are those on whom one can count to approach it. All of those I am writing about here have given me that thrill at least once—and my memory goes back to these occasions, trying to catch the incredible moment again.

(Courtesy of A. and C. Boni)

LEON ERROL. By Alfred Frueh

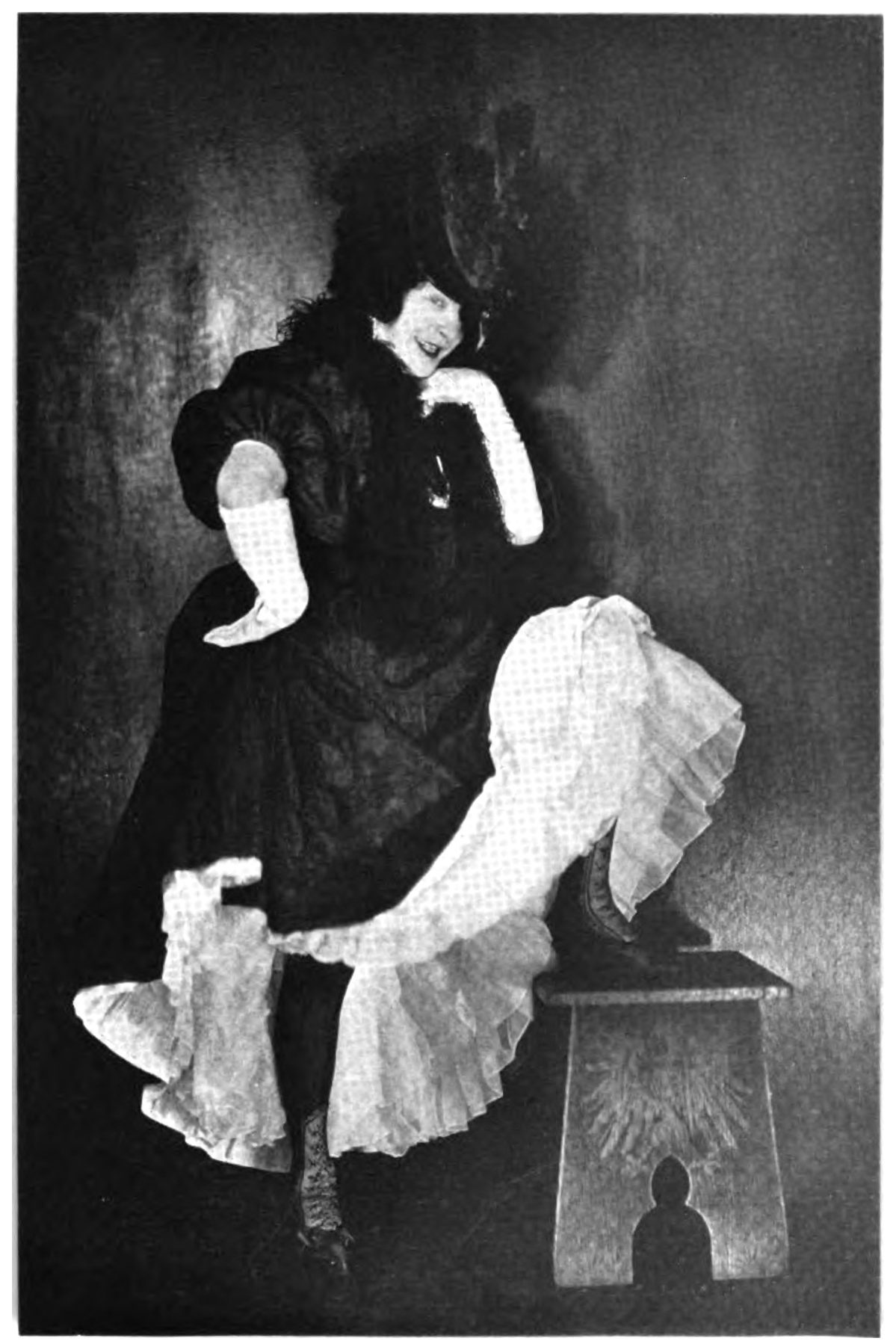

It will be impossible to communicate even the sense of it unless the material be dissociated from the event. Surely there is nothing exquisite in the roaring charwoman created by George Monroe. He had to an inspiring degree the capacity to be one of those vast figures in Dickens—Mrs Gamp to perfection—and it is odd that another impersonator, Bert Savoy, should have created, in Margie, Mrs Gamp’s own confidante and admirer, the devoted Mrs Harris. George Monroe’s creation was huge and cylindrical—more like a drainpipe than a woman in shape. There was no effort at realism, for Monroe roared in a deep bass voice, and his “Be that as it ma-a-y” was a leer in the face of all logic, order, and decency. There was in it an unrestraint, a wildness, an independent commonness which rendered it immortal. The creation of Bert Savoy is at the other extreme. It is female impersonation and the figure is always the same—the courtesan whose ambition it is to be a demi-mondaine. Savoy makes capital of all his defects down to the rakish slanting hat over one eye. His repetitions, apparently so spontaneous, are beautifully timed and spaced; the buzz and pause in the voice—“you muzzt com’over ... you don’t know the ha-ff of it, dear-ie” fix themselves in memory. He is remembered for the excellent stories he tells, and they are worth it, but the interpolations are funnier than the climax. The audacity is colossal and disarming. The occurrence of a character out of Petronius on our stage is exceptional in itself, that it should at the same time be slightly vicious and altogether charming, funny and immoral and delicate, is the wonder.

Last year there was an added touch, when Savoy danced while he sang a stanza about the Widow Brown. It was as delicate, it passed as quickly, as breath on a windowpane.15

I repeat the material doesn’t matter. For Leon Errol has nothing but the type drunkard to work with, and is wonderful. In his case it is easy to analyse the basis of the effect—it is in the loping dance step into which he converts the lurch of the drunkard. The tawdry moment—funny enough if you can bear it—is always Errol’s breathing into someone else’s face; the great moment comes directly after, when the lurch and the fall are worked up into a complete arc of dance steps, ending in three little hops as a sort of proof of sobriety. Jimmy Barton has the same quality in his skating scene—he uses less material and the movement round the rink is beautiful to watch. But of him it is useless to speak. Someone has pointed out that he can slap the bare back of a woman and make that funny!

It is interesting to see how many of the people who give this special quality arrive out of burlesque. Harry Kelly is another. I recall him first with Lizzie the Fish Hound in Watch Your Step and last in a quite useless musical comedy, The Springtime of Youth (textually that was the title—and in 1922!) For two acts he was wholly wasted. In the third he was magnificent. He was playing the obdurate father: “No son of mine shall ever marry a daughter of the Baxters” was his line. He was informed that she was, in fact, an adopted daughter and that her uncle had left her the bulk of his fortune. For precisely a minute and a half Kelly played with the word “bulk”—one saw it registered in his brain, saw an idea germinating, felt it working forward to the jaw before the cavernous voice gave it utterance—and again one felt the inner struggle not to say it a third time, one felt the conflict of pride and avarice. It was remarkably delicate and fine—so is all of Kelly’s work when he has a chance. His spare figure, long hands, and unbelievable voice always create a character—and it isn’t always the same character.

Bobby Clarke’s scene with the lion comes at once to mind (it is another burlesque act), and Bert Williams—in many scenes—always soft spoken, always understanding his case. There were five minutes of Blanche Ring and Charles Winninger, once, at the Winter Garden; to my surprise, there were more than that for Eugene and Willie Howard at the same house, but they were gained in spite of the Winter Garden technique which underestimates even the lowest intelligence. Willie is rather like Fanny Brice at moments; when he cuts loose one has an agreeable sense of uncertainty. Joe Jackson,16 actually a great clown, although one doesn’t recognize this in the highly developed medium he chooses, has exactly the opposite effect—he doesn’t cut loose at all; he develops. Everything he does is careful and nothing exaggerated, so you think at first that, although he will be funny, he will not quite reach that top notch on which an artist teeters perilously while you wonder whether he will fall over or keep his balance. Yet Jackson gets there. As the tramp cyclist his acrobatics are good, his make-up enchanting; but his expressed attitude of mind is his most precious quality. It becomes almost too much to watch him worrying with a motor horn which has become detached from the handlebars and which he cannot replace. He tries it everywhere; at the end he is miserably trying to hang it up on the air, and when it fails to catch there he is actually wretched. His movements are full of grace—like those of the grotesque, Alberto, among the Fratellini—and the ecstasy he gives comes by a surexcess of laughter. Another moment of great delicacy, without laughter, however, is that in which Fortunello and Cirrilino swing about on the broomstick. They are a lovely pair, and the little one seated on the palm of the other’s hand is a beautiful picture.

BERT SAVOY

Either few women are brought out of burlesque, or women haven’t the exceptional quality I care for. In any case they have seldom given me the excess of emotion by what they have done. Their beauty is quite another matter on which I fail to commit myself. Ada Lewis, in her broad and grand way, has the stuff, and Florence Moore. And once in each performance you can be sure that Gilda Grey will utter a sound or tremble herself into a bacchanalian revel. For the most part her singing is undistinguished, and I do not care for the anxious way in which she regards her members, as if she fancied they would fall off by dint of shimmying. Yet I have never gone to a show of hers without hearing some echo of the nymphs pursued, or seeing a movement of abandon and grace. The dark shuddering voice is sub-human, the movement divinely animal.

Different in every way, but exquisite in every way, was Gaby Deslys. It is good form now to belittle her; she was so vulgar; she came so much on the crest of a revolution, she was such a bidder for our great precious commodity—news space. Ah, well! we have given publicity to less worthy causes. For she was perfect of her type, and in her hard, calculating, sublimely decent way she made us like the type. It was gently vicious—the whole manner. It was overdone—the pearls and the peacock feathers. But behind was a lovely person—lovely to look at and enchanting to all the senses. No, she couldn’t act—how pitiable her loyal efforts; she sang badly; she wasn’t one of the world’s great dancers. But she had something irreducible, not to be hindered or infringed upon—her definite self. She was, to begin with, outcast of our moral system, and she made us accept her because she was an independent human being. She had a sound and accurate sense of her personal life, of her rights as an individual. Nothing could stand against her—and it is said that when she was at grips, at the end, with something more powerful than popular taste, she still held her own, and died rather than suffer the spoiling of her beauty. If that were true one could hardly wish even her beauty back again.