THE “VULGAR” COMIC STRIP

OF all the lively arts the Comic Strip is the most despised, and with the exception of the movies it is the most popular. Some twenty million people follow with interest, curiosity, and amusement the daily fortunes of five or ten heroes of the comic strip, and that they do this is considered by all those who have any pretentions to taste and culture as a symptom of crass vulgarity, of dulness, and, for all I know, of defeated and inhibited lives. I need hardly add that those who feel so about the comic strip only infrequently regard the object of their distaste.

Certainly there is a great deal of monotonous stupidity in the comic strip, a cheap jocosity, a life-of-the-party humour which is extraordinarily dreary. There is also a quantity of bad drawing and the intellectual level, if that matters, is sometimes not high. Yet we are not actually a dull people; we take our fun where we find it, and we have an exceptional capacity for liking the things which show us off in ridiculous postures—a counterpart to our inveterate passion for seeing ourselves in stained-glass attitudes. And the fact that we do care for the comic strip—that Jiggs and Mutt-and-Jeff and Skinnay and the Gumps have entered into our existence as definitely as Roosevelt and more deeply than Pickwick—ought to make them worth looking at, for once. Certainly they would have been more sharply regarded if they had produced the counterpart of Chaplin in the comic film—a universal genius capable of holding the multitude and exciting the speculations of the intellectuals. It happens that the actual genius of the comic strip, George Herriman, is of such a special sort that even when he is recognized he is considered something apart and his appearance among other strips is held to be only an accident.

It is by no means an accident, for the comic strip is an exceptionally supple medium, giving play to a variety of talents, to the use of many methods, and it adapts itself to almost any theme. The enormous circulation it achieves imposes certain limitations: it cannot be too local, since it is syndicated throughout the country; it must avoid political and social questions because the same strip appears in papers of divergent editorial opinions; there is no room in it for acute racial caricature, although no group is immune from its mockery. These and other restrictions have gradually made of the comic strip a changing picture of the average American life—and by compensation it provides us with the freest American fantasy.

In a book which appeared about two years ago, Civilization in the United States, thirty Americans rendered account of our present state. One of them, and one only, mentioned the comic strip—Mr Harold E. Stearns—and he summed up the “intellectual” attitude perfectly by saying that Bringing Up Father will repay the social historian for all the attention he gives it. I do not know in what satisfactions the social historian can be repaid. I fear that the actual fun in the comic strip is not one of them. Bringing Up Father, says Mr Stearns, “symbolizes better than most of us appreciate the normal relation of American men and women to cultural and intellectual values. Its very grotesqueness and vulgarity are revealing” (italics mine). (Query: Is it vulgar of Jiggs to prefer Dinty’s café to a Swami’s lecture? Or of Mrs Jiggs to insist on the lecture? Or of both of them to be rather free in the matter of using vases as projectiles? What, in short, is vulgar?) I am far from quarreling with Mr Stearns’ leading idea, for I am sure that a history of manners in the United States could be composed with the comic strip as its golden thread; but I think that something more than its vulgarity would be revealing.

The daily comic strip arrived in the early ’nineties—perhaps it was our contribution to that artistic age—and has gone through several phases. In 1892 or thereabouts Jimmy Swinnerton created Little Bears and Tigers for the San Francisco Examiner; that forerunner has passed away, but Swinnerton remains, and everything he does is observed with respect by the other comic-strip artists; he has had more influence on the strip even than Wilhelm Busch, the German whose Max und Moritz were undoubtedly the originals of the Katzenjammer Kids. The strip worked its way east, prospered by William Randolph Hearst especially in the coloured Sunday Supplement, and as a daily feature by the Chicago Daily News, which was, I am informed, the first to syndicate its strips and so enabled Americans to think nationally. About fifteen years ago, also in San Francisco, appeared the first work of Bud Fisher, Mr Mutt, soon to develop into Mutt and Jeff, the first of the great hits and still one of the best known of the comic strips. Fisher’s arrival on the scene corresponds to that of Irving Berlin in ragtime. He had a great talent, hit upon something which took the popular fancy, and by his energy helped to establish the comic strip as a fairly permanent idea in the American newspaper.

The files of the San Francisco Chronicle will one day be searched by an enthusiast for the precise date on which Little Jeff appeared in the picture. It is generally believed that the two characters came on together, but this is not so. In the beginning Mr Mutt made his way alone; he was a race-track follower who daily went out to battle and daily fell. Clare Briggs had used the same idea in his Piker Clerk for the Chicago Tribune. The historic meeting with Little Jeff, a sacred moment in our cultural development, occurred during the days before one of Jim Jeffries’ fights. It was as Mr Mutt passed the asylum walls that a strange creature confided to the air the notable remark that he himself was Jeffries. Mutt rescued the little gentleman and named him Jeff. In gratitude Jeff daily submits to indignities which might otherwise seem intolerable.

The development in the last twenty years has been rapid, and about two dozen good comics now exist. Historically it remains to be noted that between 1910 and 1916 nearly all the good comics were made into bad burlesque shows; in 1922 the best of them was made into a ballet with scenario and music by John Alden Carpenter, choreography by Adolph Bolm; costumes and settings after designs by George Herriman. Most of the comics have also appeared in the movies; the two things have much in common and some day a thesis for the doctorate in letters will be written to establish the relationship. The writer of that thesis will explain, I hope, why “movies” is a good word and “funnies,” as offensive little children name the comic pages, is what charming essayists call an atrocious vocable.

Setting apart the strip which has fantasy—it is practised by Frueh and by Herriman—the most interesting form is that which deals satirically with every-day life; the least entertaining is the one which takes over the sentimental magazine love-story and carries it through endless episodes. The degree of interest points to one of the virtues of the comic strip: it is a great corrective to magazine-cover prettiness. Only one or two frankly pretty-girl strips exist. Petey is the only one which owes its popularity to the high, handsome face and the lovely flanks of its heroine, and even there the pompous awkwardness of the persistent lover has a touch of wilful absurdity. Mrs Trubble, a second-rate strip unworthy of its originator, is simply a series of pictures dramatizing the vampire home-breaker; I am not even sure she is intended to be pretty. When nearly everything else in the same newspapers is given over to sentimentality and affected girl-worship, to advice to the lovelorn and pretty-prettiness, it is notable that the comic strip remains grotesque and harsh and careless. It is largely concerned with the affairs of men and children, and, as far as I know, there has never been an effective strip made by, for, or of a woman. The strip has been from the start a satirist of manners; remembering that it arrived at the same time as the Chicago World’s Fair, recalling the clothes, table manners, and conversation of those days, it is easy to see how the murmured satiric commentary of the strip undermined our self-sufficiency, pricked our conceit, and corrected our gaucherie. To-day the world of Tad, peopled with cake-eaters and finale-hoppers, the world of the Gumps and Gasoline Alley, of Abie the Agent and Mr and Mrs serve the same purpose. I am convinced that none of our realists in fiction come so close to the facts of the average man, none of our satirists are so gentle and so effective. Of course they are all more serious and more conscious of their mission; but—well, exactly who cares?

|

|

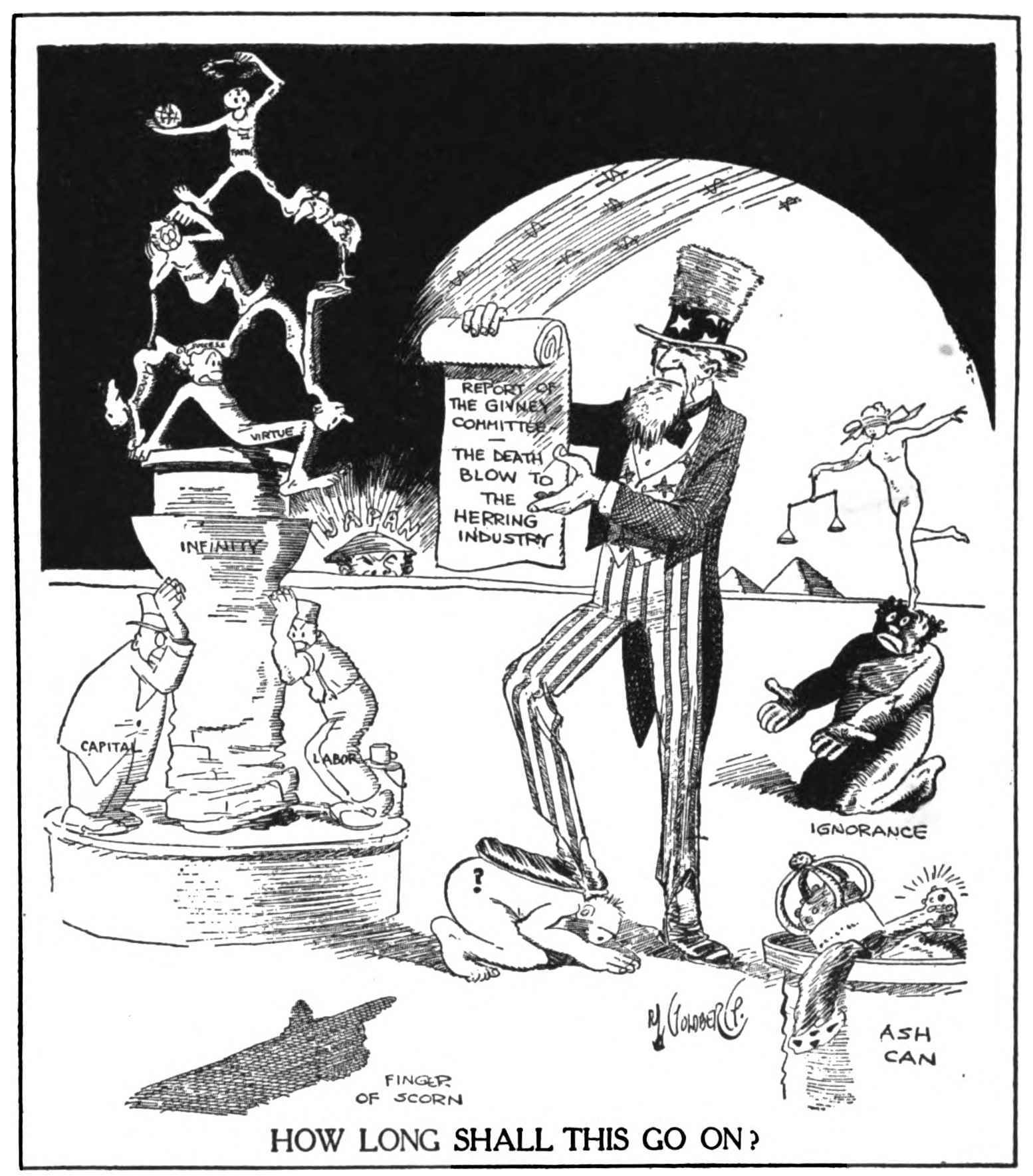

(Copyright by the Star Company. By permission of the publishers of the New York Journal)

MIKE AND MIKE. By T. E. Powers

The best of the realists is Clare Briggs, who is an elusive creator, one who seems at times to feel the medium of the strip not exactly suited to him, and at others to find himself at home in it. His single pictures: The Days of Real Sport and When a Feller Needs a Friend, and the now rapidly disappearing Kelly Pool which was technically a strip, are notable recreations of simple life. Few of them are actively funny; some are sentimental. The children of The Days of Real Sport have an astonishing reality—and none are more real than the virtually unseen Skinnay, who is always being urged to “come over.” They are a gallery of country types, some of them borrowed from literature—the Huck Finn touch is visible—but all of them freshly observed and dryly recorded. Briggs’ line is distinctive; one could identify any square inch of his drawings. In Kelly Pool he worked close to Tad’s Indoor Sports, and did what Tad hasn’t done—created a character, the negro waiter George whom I shall be sorry to lose. George’s amateur interest in pool was continually being submerged in his professional interest: gettings tips, and his “Bad day ... ba-a-ad day” when tips were low is a little classic. Deserting that scene, Briggs has made a successful comedy of domestic life in Mr and Mrs. No one has come so near to the subject—the grumbling, helpless, assertive, modest, self-satisfied, self-deprecating male, in his contacts with his sensible, occasionally irritable, wife. As often as not these episodes end in quarrels—in utter blackness with harsh bedroom voices continuing a day’s exacerbations; again the reconciliations are mushy, again they are genuine sentiment. And around them plays the child whose one function is to say “Papa loves mamma” at the most appropriate time. It is quite an achievement, for Briggs has made the ungrateful material interesting, and I can recall not one of these strips in which he has cracked a joke. Tad here follows Briggs, respectfully. For Better or Worse is considerably more obvious, but it has Tad’s special value, in sharpness of caricature. The surrounding types are brilliantly drawn; only the central characters remain stock figures. Yet the touch of romance in Tad, continually overlaid by his sense of the ridiculous, is precious; he seems aware of the faint aspirations of his characters and recognizes the rôles which they think they are playing while he mercilessly shows up their actuality. The finest of the Indoor Sports are those in which two subordinate characters riddle with sarcasm the pretentions of the others—the clerk pretending to be at ease when the boss brings his son into the office, the lady of the house talking about the new motor car, the small-town braggart and the city swell—characters out of melodrama, some, and others so vividly taken from life that the very names Tad gives them pass into common speech. He is an inveterate creator and manipulator of slang; whatever phrase he makes or picks up has its vogue for months and his own variations are delightful. Slang is a part of their picture, and he and Walter Hoban are the only masters of it.

Ketten’s Day of Rest is another strip of this genre, interesting chiefly as a piece of draughtsmanship. He is the most economical of the comic-strip artists, and his flat characters, without contours or body, have a sort of jack-in-the-box energy and a sardonic obstinacy. The Chicago School I have frankly never been able to understand—a parochialism on my part, or a tribute to its exceptional privacy and sophistication. It pretends, of course, to be simple, but the fate of every metropolis is to enter its small-town period at one time or another, to call itself a village, to build a town hall and sink a town pump with a silver handle. The Gumps are common people and the residents of Gasoline Alley are just folks, but I have never been able to understand what they are doing; I suspect they do nothing. It seems to me I read columns of conversation daily, and have to continue to the next day to follow the story. The campaign of Andy Gump for election to the Senate gave a little body to the serial story—he was so abysmally the ignorant Congressman that he began to live. But apart from this, apart from the despairing cry of “Oh, Min,” one recalls nothing of the Chicago School except the amusing vocabulary of Syd Smith and that Andy has no chin. It is an excellent symbol; but it isn’t enough for daily food.

The small-town school of comic strip flourishes in the work of Briggs, already mentioned, in Webster’s swift sketches of a similar nature, and in Tom MacNamara’s Us Boys. The last of these is an exceptional fake as small-town, but an amusing and genuine strip. It is people by creation of fancy—the alarmingly fat, amiable Skinny, the truculent Eaglebeak Spruder, the little high-brow Van with his innocence and his spectacles, and Emily, if I recall the name, the village vampire at the age of seven. Little happens in Us Boys, but MacNamara has managed to convey a genuine emotion in tracing the complicated relations between his personages—there is actual childhood friendship, actual worry and pride and anger—all rather gently rendered, and with a recognizable language.

It is interesting to note that none of these strips make use of the projectile or the blow as a regular dénoûement. I have nothing against the solution by violence of delicate problems, but since the comic strip is supposed to be exclusively devoted to physical exploits I think it is well to remark how placid life is in at least one significant branch of the art. In effect all the themes of the comic strip are subjected to a great variety of treatments, and in each of them you will find, on occasions, the illustrated joke. This is the weakest of the strips, and, as if aware of its weakness, its creators give it the snap ending of a blow, or, failing that, show us one character in consternation at the brilliance of the other’s wit, flying out of the picture with the cry of “Zowie,” indicating his surcharge of emotion. This is not the same thing as the wilful violence of Mutt and Jeff, where the attack is due to the malice or stupidity of one character, the resentment or revenge of the other.

Mutt is a picaro, one of the few rogues created in America. There is nothing too dishonest for him, nor is there any chance so slim that he won’t take it. He has an object in life: he does not do mean or vicious things simply for the pleasure of doing them, and so is vastly superior to the Peck’s Bad Boy type of strip which has an apparently endless vogue—the type best known in The Katzenjammer Kids. This is the least ingenious, the least interesting as drawing, the sloppiest in colour, the weakest in conception and in execution, of all the strips, and it is the one which has determined the intellectual idea of what all strips are like. It is now divided into two—and they are equally bad. How happy one could be with neither! The other outstanding picaresque strip is Happy Hooligan—the type tramp—who with his brother, Gloomy Gus, had added to the gallery of our national mythology. Non est qualis erat—the spark has gone out of him in recent years.17 Elsewhere you still find that exceptionally immoral and dishonest attitude toward the business standards of America. For the comic strip, especially after you leave the domestic-relations type which is itself realistic and unsentimental, is specifically more violent, more dishonest, more tricky and roguish, than America usually permits its serious arts to be. The strips of cleverness: Foxy Grandpa, the boy inventor, Hawkshaw the Detective, haven’t great vogue. Boob McNutt, without a brain in his head, beloved by the beautiful heiress, has a far greater following, although it is the least worthy of Rube Goldberg’s astonishing creations. But Mutt and Jiggs and Abie the Agent, and Barney Google and Eddie’s Friends have so little respect for law, order, the rights of property, the sanctity of money, the romance of marriage, and all the other foundations of American life, that if they were put into fiction the Society for the Suppression of Everything would hale them incontinently to court and our morals would be saved again.

The Hall-room Boys (now known as Percy and Ferdy, I think) are also picaresque; the indigent pretenders to social eminence who do anything to get on. They are great bores, not because one foresees the denunciation at the end, but because they somehow fail to come to life, and one doesn’t care whether they get away with it or not.

Abie and Jerry on the Job are good strips because they are self-contained, seldom crack jokes, and have each a significant touch of satire. Abie is the Jew of commerce and the man of common sense; you have seen him quarrel with a waiter because of an overcharge of ten cents, and, encouraged by his companion, replying, “Yes, and it ain’t the principle, either; it’s the ten cents.” You have seen a thousand tricks by which he once sold Complex motor cars and now promotes cinema shows or prize fights. He is the epitome of one side of his race, and his attractiveness is as remarkable as his jargon. Jerry’s chief fault is taking a stock situation and prolonging it; his chief virtue, at the moment, is his funny, hard-boiled attitude towards business. Mr Givney, the sloppy sentimentalist who is pleased because some one took him for Mr Taft (“Nice, clean fun,” says Jerry of that), is faced with the absurd Jerry, who demolishes efficiency systems and the romance of big business and similar nonsense with his devastating logic or his complete stupidity. The railway station at Ammonia hasn’t the immortal character of The Toonerville Trolley (that meets all the trains) because Fontaine Fox has a far more entertaining manner than Hoban, and because Fox is actually a caricaturist—all of his figures are grotesque, the powerful Katinka or Aunt Eppie not more so than the Skipper. Hoban and Hershfield both understate; Fox exaggerates grossly; but with his exaggeration he is so ingenious, so inventive that each strip is funny and the total effect is the creation of character in the Dickens sense. It is not the method of Mutt and Jeff nor of Barney Google in which Billy de Beck has done much with a luckless wight, a sentimentalist, and an endearing fool all rolled into one.

These are the strips which come to life each day, without forcing, and which stay long in memory. I am stating the case for the strip in general and have gone so far as to speak well of some I do not admire, nor read with animation. The continued existence of others remains a mystery to me; why they live beyond change, and presumably beyond accidental death, is one of the things no one can profitably speculate upon. I do not see why I should concede anything more to the enemies of the strip. In one of Life’s burlesque numbers there was a page of comics expertly done by j held in the manner of our most popular artists. Each of the half dozen strips illustrated the joke: “Who was that lady I seen you with on the street last night?” “That wasn’t a lady; that was my wife.” Like so many parodies, this arrived too late, for the current answer is, “That wasn’t a street; that was an alley.” Each picture ended in a slam and a cry—also belated. The actual demolition of the slam ending was accomplished by T. E. Powers, who touches the field of the comic strip rarely, and then with his usual ferocity. In a footnote to a cartoon he drew Mike and Mike. In six pictures four represented one man hitting the other; once to emphasize a pointless joke, twice thereafter for no reason at all, and finally to end the picture. It was destruction by exaggeration; and no comic strip artist missed the point.

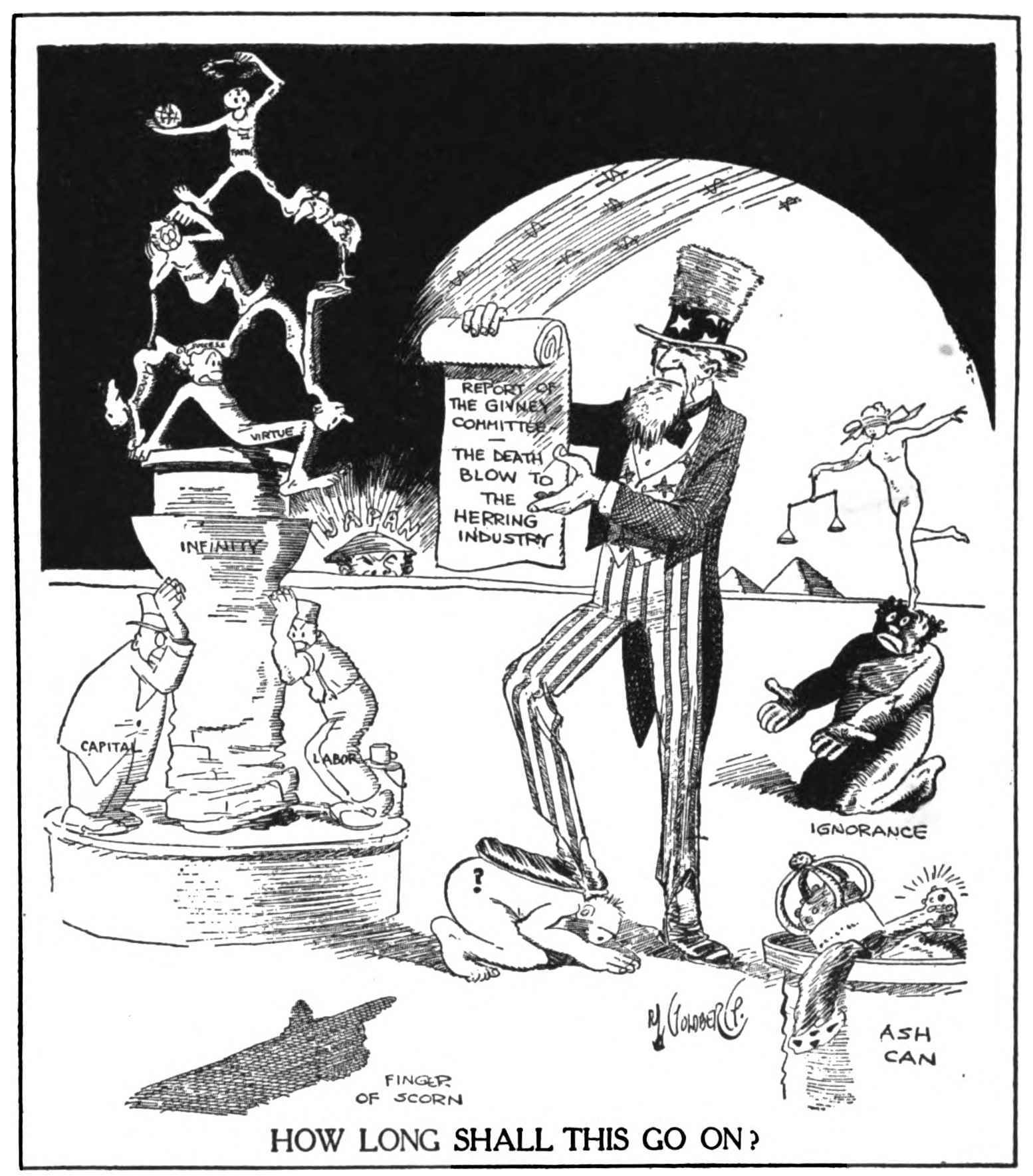

At the extremes of the comic strip are the realistic school and the fantastic—and of fantasy there are but few practitioners. Tad has some of the quality in Judge Rummy, but for the most part the Judge and Fedink and the rest are human beings dressed up as dogs—they are out of Æsop, not out of LaFontaine. But the Judge is actually funny, and I recall an inhuman and undoglike episode in which he and Fedink each claimed to have the loudest voice, and so in midwinter, in a restaurant, each lifted up his voice and uttered and shouted and bellowed the word “Strawberries” until they were properly thrown into the street. This is the kind of madness which is required in fantasy, and Goldberg occasionally has it. He is the most versatile of the lot; he has created characters, and scenes, and continuous episodes—foolish questions and meetings of ladies’ clubs and inventions (not so good as Heath Robinson’s) and through them there has run a wild grotesquerie. The tortured statues of his décors are marvelous, the way he pushes stupidity and ugliness to their last possible point, and humour into everything, is amazing. Yet I feel he is manqué, because he has never found a perfect medium for his work.

Frueh is a fine artist in caricature and could have no such difficulty. When he took it into his head to do a daily strip he was bound to do something exceptional, and he succeeded. It is a highly sophisticated thing in its humour, in its subjects, and pre-eminently in its execution. His series on prohibition enforcement had infinite ingenuity, so also his commentaries on political events in New York city. He remains a caricaturist in these strips, indicating, by his use of the medium, that its possibilities are not exhausted. Yet for all his dealing with “ideas” his method remains fantastic, and although he isn’t technically a comic-strip artist he is the best approach to the one artist whom I have only mentioned, George Herriman, and to his immortal creation. For there is, in and outside the comic strip, a solitary and incomprehensible figure which must be treated apart. The Krazy Kat that Walks by Himself.

HOW LONG SHALL THIS GO ON?

(Courtesy of Life—from the burlesque Sunday Supplement Number)

A CARTOON. By R. L. Goldberg

|

|