THE KRAZY KAT THAT WALKS BY HIMSELF

KRAZY KAT, the daily comic strip of George Herriman is, to me, the most amusing and fantastic and satisfactory work of art produced in America to-day. With those who hold that a comic strip cannot be a work of art I shall not traffic. The qualities of Krazy Kat are irony and fantasy—exactly the same, it would appear, as distinguish The Revolt of the Angels; it is wholly beside the point to indicate a preference for the work of Anatole France, which is in the great line, in the major arts. It happens that in America irony and fantasy are practised in the major arts by only one or two men, producing high-class trash; and Mr Herriman, working in a despised medium, without an atom of pretentiousness, is day after day producing something essentially fine. It is the result of a naïve sensibility rather like that of the douanier Rousseau; it does not lack intelligence, because it is a thought-out, a constructed piece of work. In the second order of the world’s art it is superbly first rate—and a delight! For ten years, daily and frequently on Sunday, Krazy Kat has appeared in America; in that time we have accepted and praised a hundred fakes from Europe and Asia—silly and trashy plays, bad painting, woful operas, iniquitous religions, everything paste and brummagem, has had its vogue with us; and a genuine, honest native product has gone unnoticed until in the year of grace 1922 a ballet brought it a tardy and grudging acclaim.

Herriman is our great master of the fantastic and his early career throws a faint light on the invincible creation which is his present masterpiece. For all of his other things were comparative failures. He could not find, in the realistic framework he chose, an appropriate medium for his imaginings, or even for the strange draughtsmanship which is his natural mode of expression. The Family Upstairs seemed to the realist reader simply incredible; it failed to give him the pleasure of recognizing his neighbours in their more ludicrous moments. The Dingbats, hapless wretches, had the same defect. Another strip came nearer to providing the right tone: Don Koyote and Sancho Pansy; Herriman’s mind has always been preoccupied with the mad knight of La Mancha, who reappears transfigured in Krazy Kat. And—although the inspirations are never literary—when it isn’t Cervantes it is Dickens to whom he has the greatest affinity. The Dickens mode operated in Baron Bean—a figure half Micawber, half Charlie Chaplin as man of the world. I have noted, in writing of Chaplin, Mr Herriman’s acute and sympathetic appreciation of the first few moments of The Kid. It is only fair to say here that he had himself done the same thing in his medium. Baron Bean was always in rags, penniless, hungry; but he kept his man Grimes, and Grimes did his dirty work, Grimes was the Baron’s outlet, and Grimes, faithful retainer, held by bonds of admiration and respect, helped the Baron in his one great love affair. Like all of Herriman’s people, they lived on the enchanted mesa (pronounced: ma-cey) by Coconino, near the town of Yorba Linda. The Baron was inventive; lacking the money to finance the purchase of a postage stamp, he entrusted a love letter to a carrier pigeon; and his “Go, my paloma,” on that occasion, is immortal.

Some of these characters are reappearing in Herriman’s latest work: Stumble Inn. Of this I have not seen enough to be sure. It is a mixture of fancy and realism; Mr Stumble himself is the Dickens character again—the sentimental, endearing innkeeper who would rather lose his only patron than kill a favourite turkey cock for Thanksgiving. I have heard that recently a litter of pups has been found in the cellar of the inn; so I should judge that fantasy has won the day. For it is Herriman’s bent to disguise what he has to say in creations of the animal world which are neither human nor animal, but each sui generis.

That is how the Kat started. The thought of a friendship between a cat and a mouse amused Herriman and one day he wrote them in as a footnote to The Family Upstairs. On their first appearance they played marbles while the family quarreled; and in the last picture the marble dropped through a hole in the bottom line. An office boy named Willie was the first to recognize the strange virtues of Krazy Kat. As surely as he was the greatest of office boys, so the greatest of editors, Arthur Brisbane, was the next to praise. He urged Herriman to keep the two characters in action; within a week they began a semi-independent existence in a strip an inch wide under the older strip. Slowly they were detached, were placed at one side, and naturally stepped into the full character of a strip when the Family departed. In time the Sundays appeared—three quarters of a page, involving the whole Krazy Kat and Ignatz families18 and the flourishing town of Coconino—the flora and fauna of that enchanted region which Herriman created out of his memories of the Arizona desert he so dearly loves.

In one of his most metaphysical pictures Herriman presents Krazy as saying to Ignatz: “I ain’t a Kat ... and I ain’t Krazy” (I put dots to indicate the lunatic shifting of background which goes on while these remarks are made; although the action is continuous and the characters motionless, it is in keeping with Herriman’s method to have the backdrop in a continual state of agitation; you never know when a shrub will become a redwood, or a hut a church) ... “it’s wot’s behind me that I am ... it’s the idea behind me, ‘Ignatz’ and that’s wot I am.” In an attitude of a contortionist Krazy points to the blank space behind him, and it is there that we must look for the “Idea.” It is not far to seek. There is a plot and there is a theme—and considering that since 1913 or so there have been some three thousand strips, one may guess that the variations are infinite. The plot is that Krazy (androgynous, but according to his creator willing to be either) is in love with Ignatz Mouse; Ignatz, who is married, but vagrant, despises the Kat, and his one joy in life is to “Krease that Kat’s bean with a brick” from the brickyard of Kolin Kelly. The fatuous Kat (Stark Young has found the perfect word for him: he is crack-brained) takes the brick, by a logic and a cosmic memory presently to be explained, as a symbol of love; he cannot, therefore, appreciate the efforts of Offisa B. Pupp to guard him and to entrammel the activities of Ignatz Mouse (or better, Mice). A deadly war is waged between Ignatz and Offisa Pupp—the latter is himself romantically in love with Krazy; and one often sees pictures in which Krazy and Ignatz conspire together to outwit the officer, both wanting the same thing, but with motives all at cross-purposes. This is the major plot; it is clear that the brick has little to do with the violent endings of other strips, for it is surcharged with emotions. It frequently comes not at the end, but at the beginning of an action; sometimes it does not arrive. It is a symbol.

The theme is greater than the plot. John Alden Carpenter has pointed out in the brilliant little foreword19 to his ballet, that Krazy Kat is a combination of Parsifal and Don Quixote, the perfect fool and the perfect knight. Ignatz is Sancho Panza and, I should say, Lucifer. He loathes the sentimental excursions, the philosophic ramblings of Krazy; he interrupts with a well-directed brick the romantic excesses of his companion. For example: Krazy blindfolded and with the scales of Justice in his hand declares: “Things is all out of perpotion, ‘Ignatz.’” “In what way, fool?” enquires the Mice as the scene shifts to the edge of a pool in the middle of the desert. “In the way of ‘ocean’ for a instinct.” “Well?” asks Ignatz. They are plunging head down into mid-sea, and only their hind legs, tails, and words are visible: “The ocean is so innikwilly distribitted.” They appear, each prone on a mountain peak, above the clouds, and the Kat says casually across the chasm to Ignatz: “Take ‘Denva, Kollorado’ and ‘Tulsa, Okrahoma’ they ain’t got no ocean a tall—” (they are tossed by a vast sea, together in a packing-case) “while Sem Frencisco, Kellafornia, and Bostin, Messachoosit, has got more ocean than they can possibly use”—whereon Ignatz properly distributes a brick evenly on Krazy’s noodle. Ignatz “has no time” for foolishness; he is a realist and Sees Things as They ARE. “I don’t believe in Santa Claus,” says he; “I’m too broad-minded and advanced for such nonsense.”

But Mr Herriman, who is a great ironist, understands pity. It is the destiny of Ignatz never to know what his brick means to Krazy. He does not enter into the racial memories of the Kat which go back to the days of Cleopatra, of the Bubastes, when Kats were held sacred. Then, on a beautiful day, a mouse fell in love with Krazy, the beautiful daughter of Kleopatra Kat; bashful, advised by a soothsayer to write his love, he carved a declaration on a brick and, tossing the “missive,” was accepted, although he had nearly killed the Kat. “When the Egyptian day is done it has become the Romeonian custom to crease his lady’s bean with a brick laden with tender sentiments ... through the tide of dusty years” ... the tradition continues. But only Krazy knows this. So at the end it is the incurable romanticist, the victim of acute Bovaryisme, who triumphs; for Krazy faints daily in full possession of his illusion, and Ignatz, stupidly hurling his brick, thinking to injure, fosters the illusion and keeps Krazy “heppy.”

Not always, to be sure. Recently we beheld Krazy smoking an “eligint Hawanna cigar” and sighing for Ignatz; the smoke screen he produced hid him from view when Ignatz passed, and before the Mice could turn back, Krazy had handed over the cigar to Offisa Pupp and departed, saying “Looking at ‘Offisa Pupp’ smoke himself up like a chimly is werra werra intrisking, but it is more wital that I find ‘Ignatz’”—wherefore Ignatz, thinking the smoke screen a ruse, hurls his brick, blacks the officer’s eye, and is promptly chased by the limb of the law. Up to this point you have the usual technique of the comic strip, as old as Shakespeare. But note the final picture of Krazy beholding the pursuit, himself disconsolate, unbricked, alone, muttering: “Ah, there him is—playing tag with ‘Offisa Pupp’—just like the boom compenions wot they is.” It is this touch of irony and pity which transforms all of Herriman’s work, which relates it, for all that the material is preposterous, to something profoundly true and moving. It isn’t possible to retell these pictures; but that is the only way, until they are collected and published, that I can give the impression of Herriman’s gentle irony, of his understanding of tragedy, of the sancta simplicitas, the innocent loveliness in the heart of a creature more like Pan than any other creation of our time.

Given the general theme, the variations are innumerable, the ingenuity never flags. I use haphazard examples from 1918 to 1923, for though the Kat has changed somewhat since the days when he was even occasionally feline, the essence is the same. Like Charlot, he was always living in a world of his own, and subjecting the commonplaces of actual life to the test of his higher logic. Does Ignatz say that “the bird is on the wing,” Krazy suspects an error and after a careful scrutiny of bird life says that “from rissint obserwation I should say that the wing is on the bird.” Or Ignatz observes that Don Kiyote is still running. Wrong, says the magnificent Kat: “he is either still or either running, but not both still and both running.” Ignatz passes with a bag containing, he says, bird-seed. “Not that I doubt your word, Ignatz,” says Krazy, “but could I give a look?” And he is astonished to find that it is bird-seed, after all, for he had all the time been thinking that birds grew from eggs. It is Ignatz who is impressed by a falling star; for Krazy “them that don’t fall” are the miracle. I recommend Krazy to Mr Chesterton, who, in his best moments, will understand. His mind is occupied with eternal oddities, with simple things to which his nature leaves him unreconciled. See him entering a bank and loftily writing a check for thirty million dollars. “You haven’t that much money in the bank,” says the cashier. “I know it,” replies Krazy; “have you?” There is a drastic simplicity about Krazy’s movements; he is childlike, regarding with grave eyes the efforts of older people to be solemn, to pretend that things are what they seem; and like children he frightens us because none of our pretensions escapes him. A king to him is a “royal cootie.” “Golla,” says he, “I always had a ida they was grend, and megnifishint, and wondafil, and mejestic ... but my goodniss! It ain’t so.” He should be given to the enfant terrible of Hans Andersen who knew the truth about kings.

He is, of course, blinded by love. Wandering alone in springtime, he suffers the sight of all things pairing off; the solitude of a lonesome pine worries him and when he finds a second lonesome pine he comes in the dead of night and transplants one to the side of the other, “so that in due course, Nature has her way.” But there are moments when the fierce pang of an unrequited passion dies down. “In these blissfil hours my soul will know no strife,” he confides to Mr Bum Bill Bee, who, while the conversation goes on, catches sight of Ignatz with a brick, flies off, stings Ignatz from the field, and returns to hear: “In my Kosmis there will be no feeva of discord ... all my immotions will function in hominy and kind feelings.” Or we see him at peace with Ignatz himself. He has bought a pair of spectacles, and seeing that Ignatz has none, cuts them in two, so that each may have a monocle. He is gentle, and gentlemanly, and dear; and these divagations of his are among his loveliest moments; for when irony plays about him he is as helpless—as we are.

(Copyright by The Star Company)

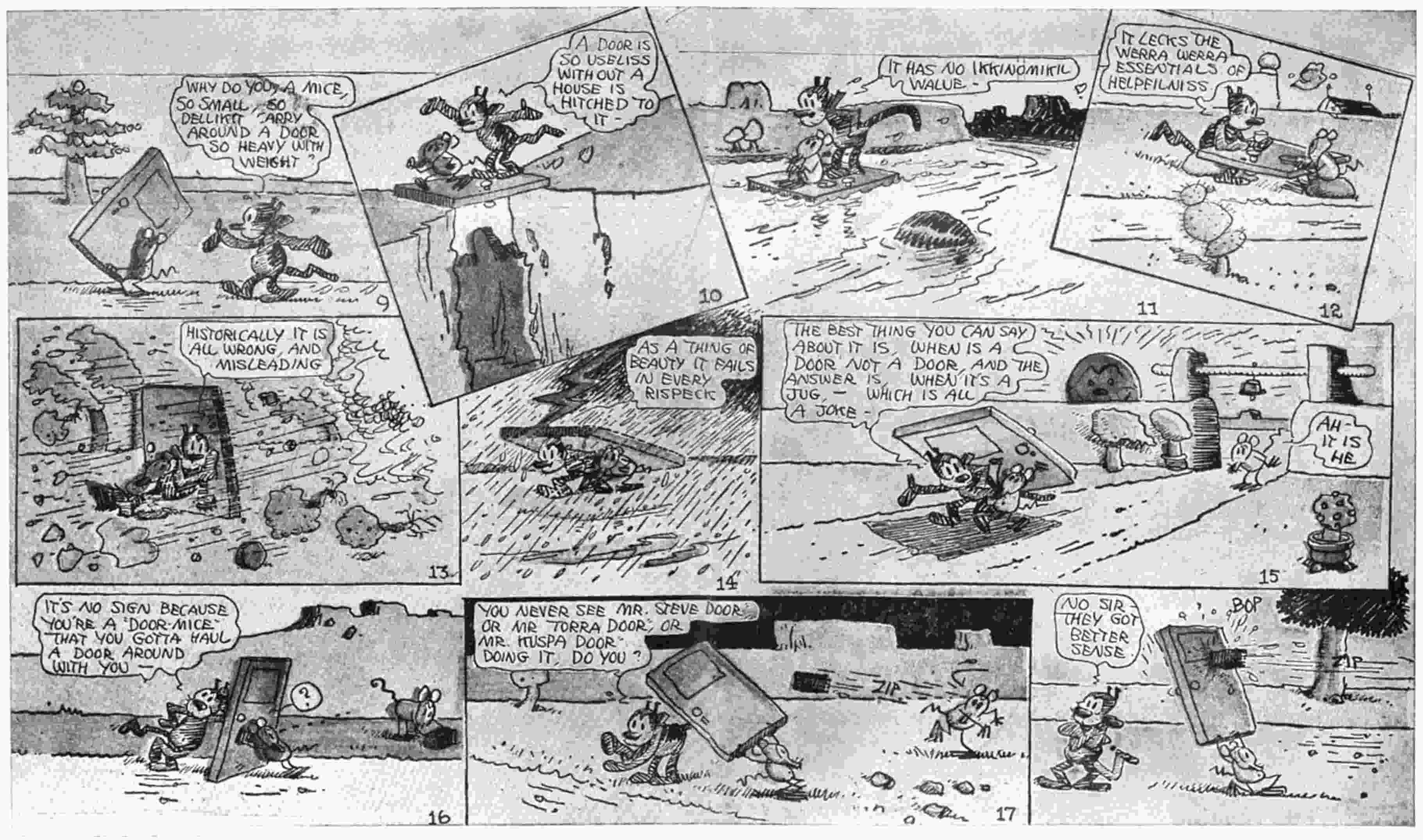

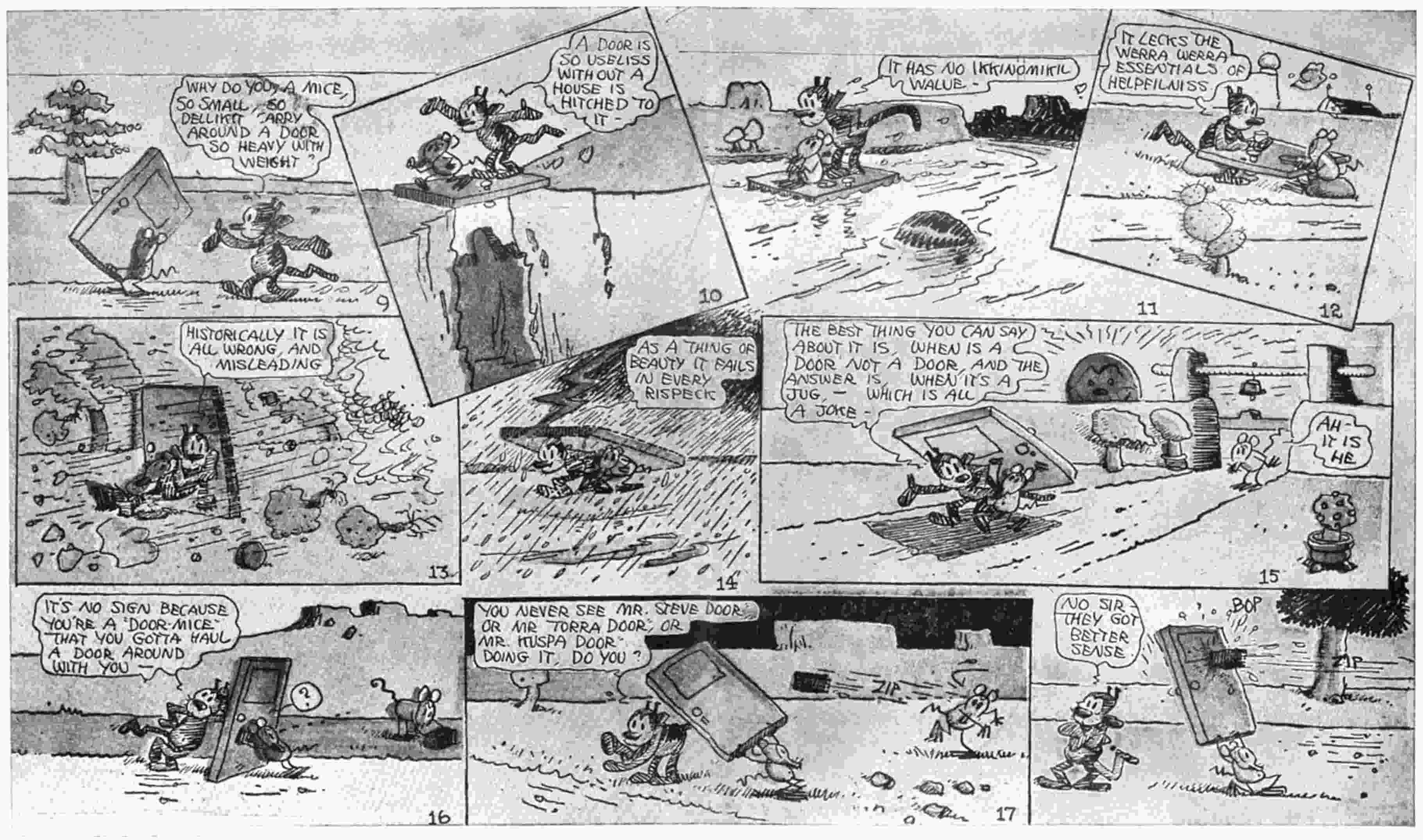

FRAGMENT FROM THE KRAZY KAT OF THE DOOR. By George Herriman.

(The original, of which this reproduces only the central episodes, is in colour. Cf. text, page 244.)

To put such a character into music was a fine thought, but Mr Carpenter must have known that he was foredoomed to failure. It was a notable effort, for no other of our composers had seen the possibilities; most, I fear, did not care to “lower themselves” by the association. Mr Carpenter caught much of the fantasy; it was exactly right for him to make the opening a parody—The Afternoon Nap of a Faun. The “Class A Fit,” the Katnip Blues were also good. (There exists a Sunday Krazy of this very scene—it is 1919, I think, and shows hundreds of Krazy Kats in a wild abandoned revel in the Katnip field—a rout, a bacchanale, a satyr-dance, an erotic festival, with our own Krazy playing the viola in the corner, and Ignatz, who has been drinking, going to sign the pledge.) Mr Carpenter almost missed one essential thing: the ecstasy of Krazy when the brick arrives at the end; certainly, as Mr Bolm danced it one felt only the triumph of Ignatz, one did not feel the grand leaping up of Krazy’s heart, the fulfilment of desire, as the brick fell upon him. The irony was missing. And it was a mistake for Bolm to try it, since it isn’t Russian ballet Krazy requires; it is American dance. One man, one man only can do it right, and I publicly appeal to him to absent him from felicity awhile, and though he do it but once, though but a small number of people may see it, to pay tribute to his one compeer in America, to the one creation equalling his own—I mean, of course, Charlie Chaplin. He has been urged to do many things hostile to his nature; here is one thing he is destined to do. Until then the ballet ought to have Johnny and Ray Dooley for its creators. And I hope that Mr Carpenter hasn’t driven other composers off the subject. There is enough there for Irving Berlin and Deems Taylor to take up. Why don’t they? The music it requires is a jazzed tenderness—as Mr Carpenter knew. In their various ways Berlin and Taylor could accomplish it.

They may not be able to write profoundly in the private idiom of Krazy. I have preserved his spelling and the quotations have given some sense of his style. The accent is partly Dickens and partly Yiddish—and the rest is not to be identified, for it is Krazy. It was odd that in Vanity Fair’s notorious “rankings,” Krazy tied with Doctor Johnson, to whom he owes much of his vocabulary. There is a real sense of the colour of words and a high imagination in such passages as “the echoing cliffs of Kaibito” and “on the north side of ‘wild-cat peak’ the ‘snow squaws’ shake their winter blankets and bring forth a chill which rides the wind with goad and spur, hurling with an icy hand rime, and frost upon a dreamy land musing in the lap of Spring”; and there is the rhythm of wonder and excitement in “Ooy, ‘Ignatz’ it’s awfil; he’s got his legs cut off above his elbows, and he’s wearing shoes, and he’s standing on top of the water.”

Nor, even with Mr Herriman’s help, will a ballet get quite the sense of his shifting backgrounds. He is alone in his freedom of movement; in his large pictures and small, the scene changes at will—it is actually our one work in the expressionistic mode. While Krazy and Ignatz talk they move from mountain to sea; or a tree stunted and flattened with odd ornaments of spots or design, grows suddenly long and thin; or a house changes into a church. The trees in this enchanted mesa are almost always set in flower pots with Coptic and Egyptian designs in the foliage as often as on the pot. There are adobe walls, fantastic cactus plants, strange fungus and growths. And they compose designs. For whether he be a primitive or an expressionist, Herriman is an artist; his works are built up; there is a definite relation between his theme and his structure, and between his lines, masses, and his page. His masterpieces in colour show a new delight, for he is as naïve and as assured with colour as with line or black and white. The little figure of Krazy built around the navel, is amazingly adaptable, and Herriman economically makes him express all the emotions with a turn of the hand, a bending of that extraordinary starched bow he wears round the neck, or with a twist of his tail.

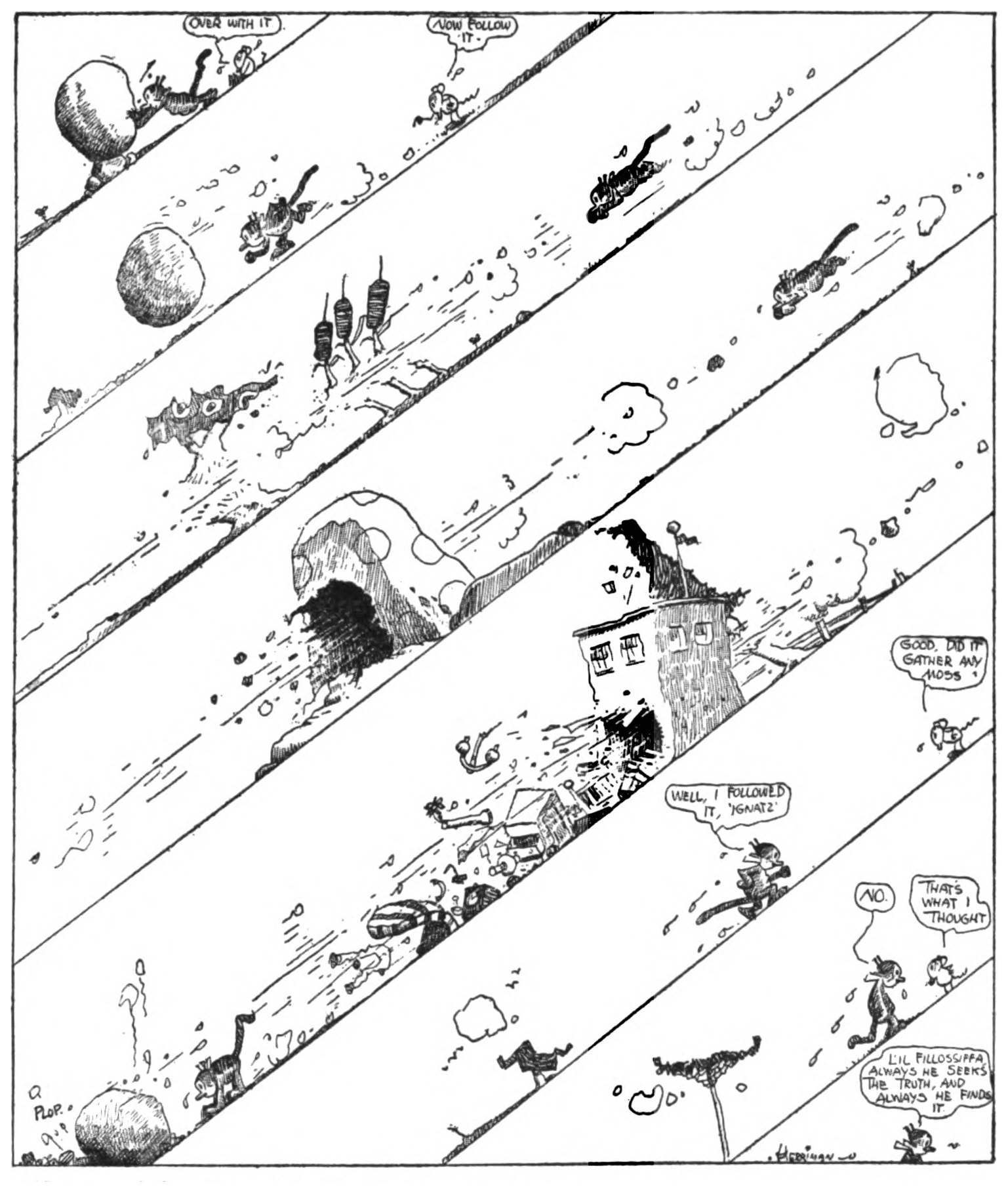

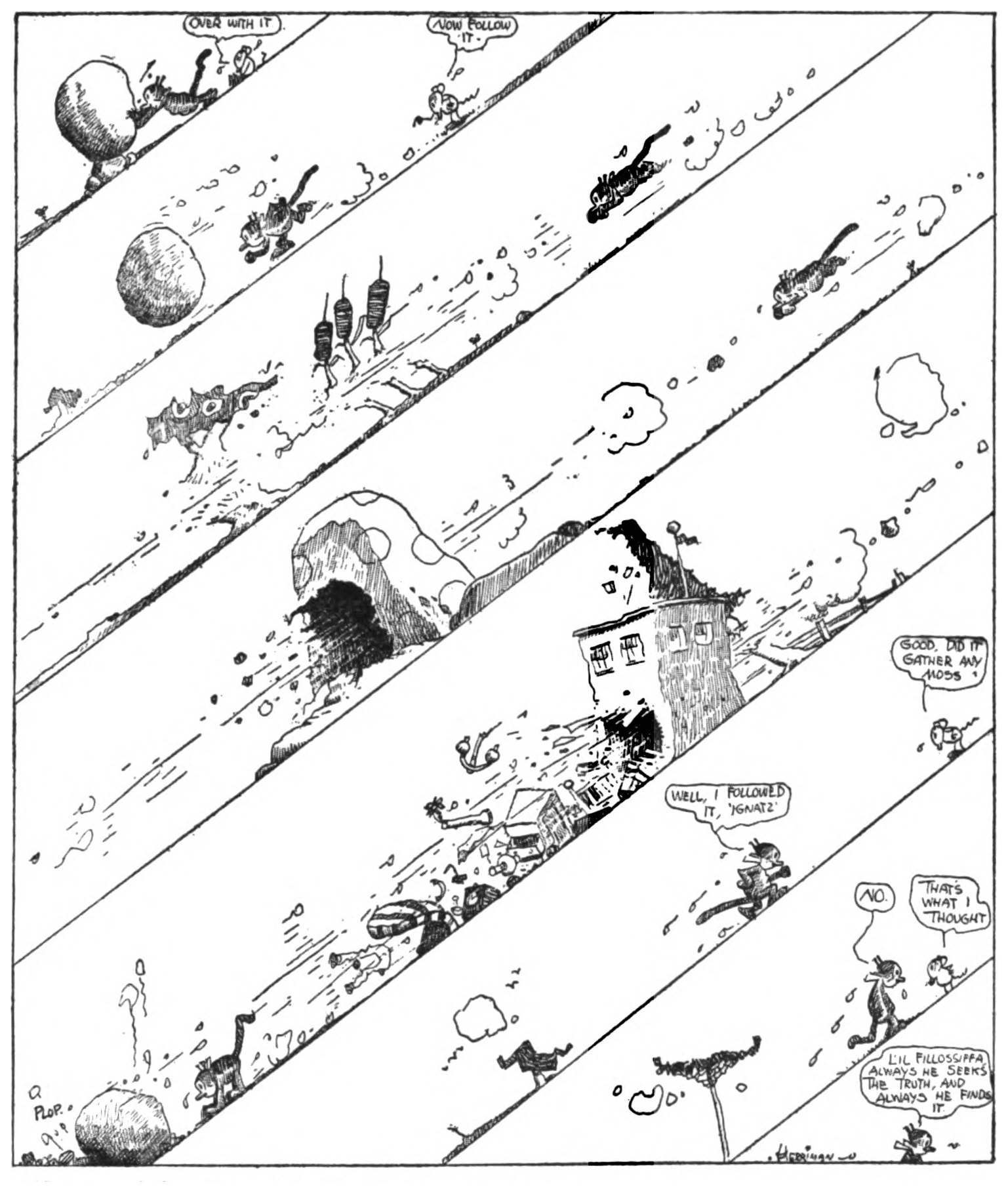

And he has had much to express for he has suffered much. I return to the vast enterprises of the Sunday pictures. There is one constructed entirely on the bias. Ignatz orders Krazy to push a huge rock off its base, then to follow it downhill. Down they go, crashing through houses, uprooting trees, tearing tunnels through mountains, the bowlder first, Krazy so intently after that he nearly crashes into it when it stops. He toils painfully back uphill. “Did it gather any moss?” asks Ignatz. “No.” “That’s what I thought.” “L’il fillossiffa,” comments Krazy, “always he seeks the truth, and always he finds it.” There is the great day in which Krazy hears a lecture on the ectoplasm, how “it soars out into the limitless ether, to roam willy-nilly, unleashed, unfettered, and unbound” which becomes for him: “Just imegine having your ‘ectospasm’ running around, William and Nilliam, among the unlimitliss etha—golla, it’s imbillivibil—” until a toy balloon, which looks like Ignatz precipitates a heroic gesture and a tragedy. And there is the greatest of all, the epic, the Odyssean wanderings of the door:

Krazy beholds a dormouse, a little mouse with a huge door. It impresses him as being terrible that “a mice so small, so dellikit” should carry around a door so heavy with weight. (At this point their Odyssey begins; they use the door to cross a chasm.) “A door is so useless without a house is hitched to it.” (It changes into a raft and they go down stream.) “It has no ikkinomikil value.” (They dine off the door.) “It lecks the werra werra essentials of helpfilniss.” (It shelters them from a hailstorm.) “Historically it is all wrong and misleading.” (It fends the lightning.) “As a thing of beauty it fails in every rispeck.” (It shelters them from the sun and while Krazy goes on to deliver a lecture: “You never see Mr Steve Door, or Mr Torra Door, or Mr Kuspa Door doing it, do you?” and “Can you imagine my li’l friends Ignatz Mice boddering himself with a door?”) his li’l friend Ignatz has appeared with the brick; unseen by Krazy he hurls it; it is intercepted by the door, rebounds, and strikes Ignatz down. Krazy continues his adwice until the dormouse sheers off, and then Krazy sits down to “concentrate his mind on Ignatz and wonda where he is at.”

(Courtesy of the artist and the New York American)

KRAZY KAT. By George Herriman

Such is our Krazy. Such is the work which America can pride itself on having produced, and can hastily set about to appreciate. It is rich with something we have too little of—fantasy. It is wise with pitying irony; it has delicacy, sensitiveness, and an unearthly beauty. The strange, unnerving, distorted trees, the language inhuman, un-animal, the events so logical, so wild, are all magic carpets and faery foam—all charged with unreality. Through them wanders Krazy, the most tender and the most foolish of creatures, a gentle monster of our new mythology.