THEY CALL IT DANCING

ONE of the most tiresome of contemporary intellectual sentimentalities is the cult of “the dance”—a cult which has almost nothing in the world to do with dancing. “The dance” is “art”; dancing is a form of popular entertainment, one of the very few which can be practised by its admirers. It is also one of the arts which can be “polite” without danger of atrophy, the danger in this case being that the technical refinement may eventually make dancing a trick, a rather graceful sort of juggling.

In any case, we shall not have in America anything corresponding to folk dances; the ritual dance, the dance as religion, simply isn’t our type, and none of the tentatives in favour of that kind of dancing has made me regret our natural bent toward ballroom and stunt dancing as a mode of expression. In the rue Lappe in Paris nearly every other house is a Bal Musette and in all but one of these dance halls the floor is taken by men and women of that quarter, working men and women who come in and dance and pay a few sous for each dance. They do this every night and enjoy it; they enjoy the sometimes wheezing accordeon and the bells which, on the right ankle of the player, accentuate the beat. They dance waltzes and polkas and, since the Java is forbidden, the mazurka. Once I saw two couples rise and dance the bourrée, presumably as it was danced in their native province of Auvergne; it is possible to see other provincial dances of France, as they are remembered, in the Bal Musette of this district and elsewhere—occasionally and not by pre-arrangement. The ancient dances of America haven’t such roots, nor such vitality; and we may have to become much more simple, or much more sophisticated, before we will proceed naturally to buck-and-wing and cakewalk and the ordinary breakdown on the floor of the Palais Royal. There are Kentucky mountain and cowboy dances which the moving picture inadequately reconstructs, and I am afraid that even negro levee dancing has lost much of its own character in the process of influencing the steps of the ordinary American dance. Undoubtedly those who can should preserve these provincial and rooted dances; but it is idle to pretend that dancing itself can be a subject for archæology. It is essentially for action, not for speculation.

I do not belittle dancing when I attempt to deprive it of the cachet of “Art.” Nothing so precise, so graceful, so implicated with music, can escape being artistic; in the hands of its masters it becomes an intuitive creative process, but this happens most frequently when the dancer gives himself to the music and seldom when he tries to interpret the music. From the waltz to the tango, from the tango to the current fox-trot or one-step, polite dancing has held more of what is essentially artistic than the art-dance, and it has had no pretensions. The old tango and the maxixe were the only ones which could not easily be danced by those who applauded them on the stage; classic dancing, on the contrary, has always been an art of professionals—almost a contradiction in terms in this case, for it is the essence of the dance that it can be danced. It is not the essence of the dance that it can be staged, or made into a pantomime. The Russian Ballet has no reference to the subject for it is essentially the work of mimes and the dancing is either folk dance or choreography.

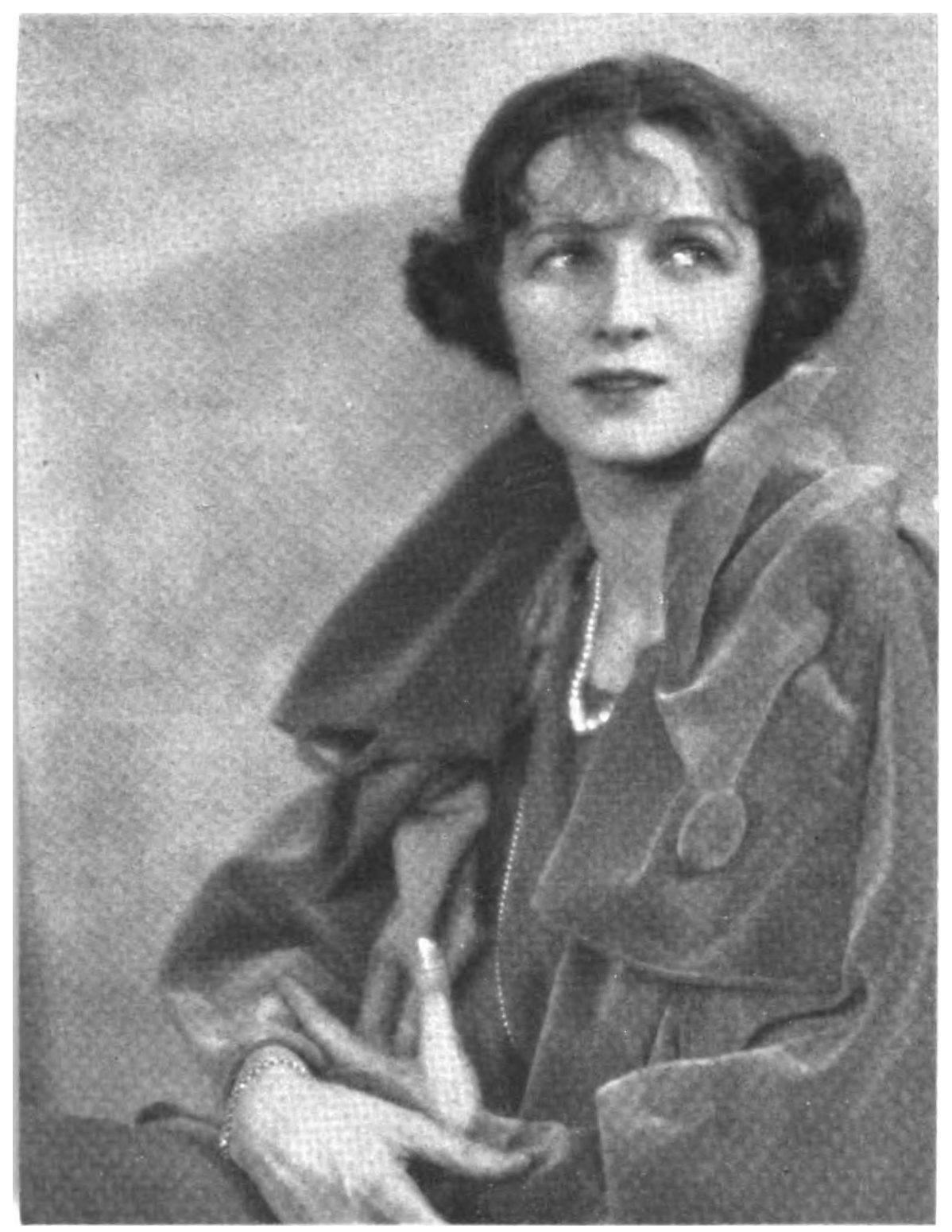

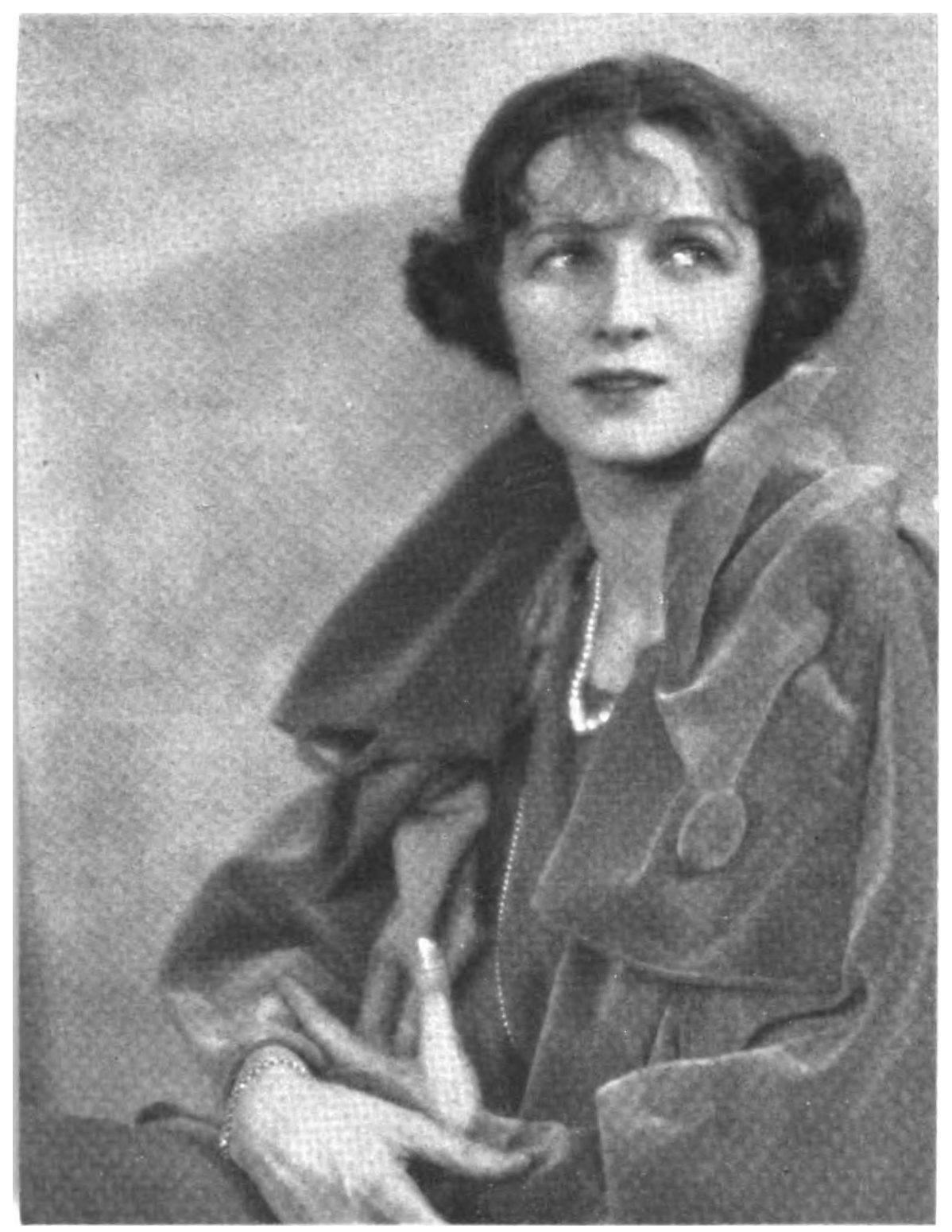

IRENE CASTLE

The reason politeness is not fatal to the dance is that there is only one standard of vulgarity in dancing, which is ugliness. Vulgarity means actively disagreeable postures and steps not exceptionally adapted to the music. The relation of the dancers to one another is the basis of their relation to the music, and that is why the shimmy has little to do with dancing, whereas the cheek-to-cheek position—the bête-noire of chaperons a few weeks, or is it years, ago?—is fundamentally not objectionable, since it brings two dancers to as near a unit, with the same centre of gravity, as the dance requires. One doesn’t dance the fox-trot as one danced the Virginia reel, and the question of morals has little to do with the case. The “indecencies” of the turkey-trot, as we used to phrase it, disappeared not because we are better men and women, but because we are dancing more beautifully.

Two influences have worked to accomplish this. One is that our music has become more interesting and is written specifically to be danced, as the waltz-song always was and as our older ragtime was not. The other is the effect of the stage (through which we have, recently, learned a vast amount from negro dancing, an active influence for the last fifteen years at least, touching the dance at every point in music, and tending always to prevent the American dance from becoming cold and formal.) Dancing masters go to the stage to perform the dances they have elaborated in their studios; from the stage the dance is adapted to the floor. This is what makes it so unnerving to go through a year seeing nothing but men jumping over their own ankles, or to witness Carl Randall dancing himself into his evening clothes. One doesn’t know how soon one will be called upon to do the same sort of thing in the semi-privacy of the night club. Acrobatic dancing is interesting as all acrobatics are—brutally for the stunt and æsthetically for the picture formed while doing the trick. The dancing of choruses has something of the same interest. The Tiller or Palace Girls do very little that would merit attention if done by one of them; done by sixteen, it is entertaining; so are the ranks of heads appearing over the top step of the Hippodrome or at the New Amsterdam, and the ranks of knees rhythmically bending as row follows row down the stairs. But none of these affect actual dancing appreciably.

Acrobatic or stunt dancing has a tendency to corrupt good exhibition dancing—the desire to do something obviously difficult displaces the more estimable desire to do something beautiful. Yet some of our best stunt dancers can and do combine all the elements and to watch them is to experience a double delight. George M. Cohan always danced interestingly; he has sardonic legs and he is, I suppose, the repository of all the knowledge we have of the 1890–1910 dance. Frisco took up the same work near the place where Cohan dropped it; he is (but where I do not know) a character dancer with a specific sense of jazz, and was, for a moment, the symbolic figure of what was coming. His eccentricities were premature, his comparative disappearance unmerited. Eccentric also, and not chiefly dancers, are Leon Errol and Jimmy Barton. Eccentric and essentially a dancer is the fine comic Johnny Dooley. The difference is that almost all of Dooley’s comedy is in his dancing, whereas the others are great comedians and their dances are also funny. It seems to be Dooley’s natural mode to walk on the side of his feet and to catch a broken, wholly American rhythm in every movement—to create dances, therefore, which are untouched by the Russian Ballet and other trepaks and hazzazzas. The foreign influence has touched Carl Randall, a gain in expertness, a loss in freshness. There seems to be nothing he cannot do, nothing he doesn’t do well, nothing he does superbly.

The dancing team which ought to have been the best of our time and wasn’t is that of Julia Sanderson and Donald Brian.21 The suppleness of Miss Sanderson’s body, the breathless sway of the torso on the hips, the suggestion of languor in the most rapid of her movements, are not to be equalled; and Brian was always smart, decisive, accurate. It is difficult to define the defect which was always in their work; probably a reserve, a not giving themselves away to the music, a shade too much of the stiffness which dancing requires. Miss Sanderson gets along quite well without the lyric knees (as they were—one doesn’t see them now) of Ann Pennington; nor has she the exceptional height which makes the grace of Jessica Brown so surprising and her curve of beauty so exceptional. Miss Brown, I take it, is one of the best dancers of the stage, and, unlike Charlotte Greenwood, has nothing to do with grotesque. Miss Greenwood makes a virtue of her defect—the longest limbs in the world. Miss Brown is unconscious of hers as defects at all; like most people’s, her legs are long enough to reach the ground. It is marvellous to see what she can do when she lifts them off the ground.

I choose these names as examples, fully aware that I may be omitting others equally famous. But what remains is deliberate: two groups of dancers who were at the very top, I think, of their profession, of their art. Of Doyle and Dixon only Harland Dixon is now visible; the team is broken, but Dixon continues to be a wonderful dancer, in the tradition rather of Fred Stone, and with recent leanings toward acting. It was 1915 or so when I saw them dance Irving Berlin’s Ragtime Melodrama, and although I have never seen that equalled, I have never seen the team or Dixon alone dance anything unworthy of that piece. It was a beautiful duo, perfectly cadenced, creating long grateful lines around the stage; it was full of tricks and fun and character. And gradually the duo resolved itself into feats of individual prowess, in which Dixon slowly surpassed his partner and became a miracle of acrobatics in rhythm. He is agile, never jerky, with a nice sense of syncopation; he requires Berlin rather than Kern for his full value.

Kern gives all (and more) that Maurice can require, and whether with Florence Walton or Leonora Hughes the dancing of Maurice is always icily regular, and nearly null. His type of mechanism is exactly wrong and he sets off in bold relief the accuracy, the inspired rightness of Irene and Vernon Castle. That these two, years ago, determined the course dancing should take is incontestable. They were decisive characters, like Boileau in French poetry and Berlin in ragtime; for they understood, absorbed, and transformed everything known of dancing up to that time and out of it made something beautiful and new. Vernon Castle, it is possible, was the better dancer of the two; in addition to the beauty of his dancing he had inventiveness, he anticipated things of 1923 with his rigid body and his evolutions on his heel; but if he were the greater, his finest creation was Irene.

No one else has ever given exactly that sense of being freely perfect, of moving without effort and without will, in more than accord, in absolute identity with music. There was always something unimpassioned, cool not cold, in her abandon; it was certainly the least sensual dancing in the world; the whole appeal was visual. It was as if the eye following her graceful motion across a stage was gratified by its own orbit, and found a sensuous pleasure in the ease of her line, in the disembodied lightness of her footfall, in the careless slope of her lovely shoulders. It was not—it seemed not to be—intelligent dancing; however trained, it was still intuitive. She danced from her shoulders down, the straight scapular supports of her head were at the same time the balances on which her exquisitely poised body depended. There were no steps, no tricks, no stunts. There was only dancing, and it was all that one ever dreamed of flight, with wings poised, and swooping gently down to rest. I put it in the past, I hardly know why; unless because it is too good to last.