BEFORE A PICTURE BY PICASSO

For there are many arts, not among those we conventionally

call “fine,” which seem to me fundamental for living.

HAVELOCK ELLIS.

IT was my great fortune just as I was finishing this book to be taken by a friend to the studio of Pablo Picasso. We had been talking on our way of the lively arts; my companion denied none of their qualities, and agreed violently with my feeling about the bogus, what we called le côté Puccini. But he held that nothing is more necessary at the moment than the exercise of discrimination, that we must be on our guard lest we forget the major arts, forget even how to appreciate them, if we devote ourselves passionately, as I do, to the lively ones. Had he planned it deliberately he could not have driven his point home more deeply, for in Picasso’s studio we found ourselves, with no more warning than our great admiration, in the presence of a masterpiece. We were not prepared to have an unframed canvas suddenly turned from the wall and to recognize immediately that one more had been added to the small number of the world’s greatest works of art.

I shall make no effort to describe that painting. It isn’t even important to know that I am right in my judgement. The significant and overwhelming thing to me was that I held the work a masterpiece and knew it to be contemporary. It is a pleasure to come upon an accredited masterpiece which preserves its authority, to mount the stairs and see the Winged Victory and know that it is good. But to have the same conviction about something finished a month ago, contemporaneous in every aspect, yet associated with the great tradition of painting, with the indescribable thing we think of as the high seriousness of art and with a relevance not only to our life, but to life itself—that is a different thing entirely. For of course the first effect—after one had gone away and begun to be aware of effects—was to make one wonder whether it is worth thinking or writing or feeling about anything else. Whether, since the great arts are so capable of being practised to-day, it isn’t sheer perversity to be satisfied with less. Whether praise of the minor arts isn’t, at bottom, treachery to the great. I had always believed that there exists no such hostility between the two divisions of the arts which are honest—that the real opposition is between them, allied, and the polished fake. To that position I returned a few days later: it was a fortunate week altogether, for I heard the Sacre du Printemps of Strawinsky the next day, and this tremendous shaking of the forgotten roots of being gave me reassurance.

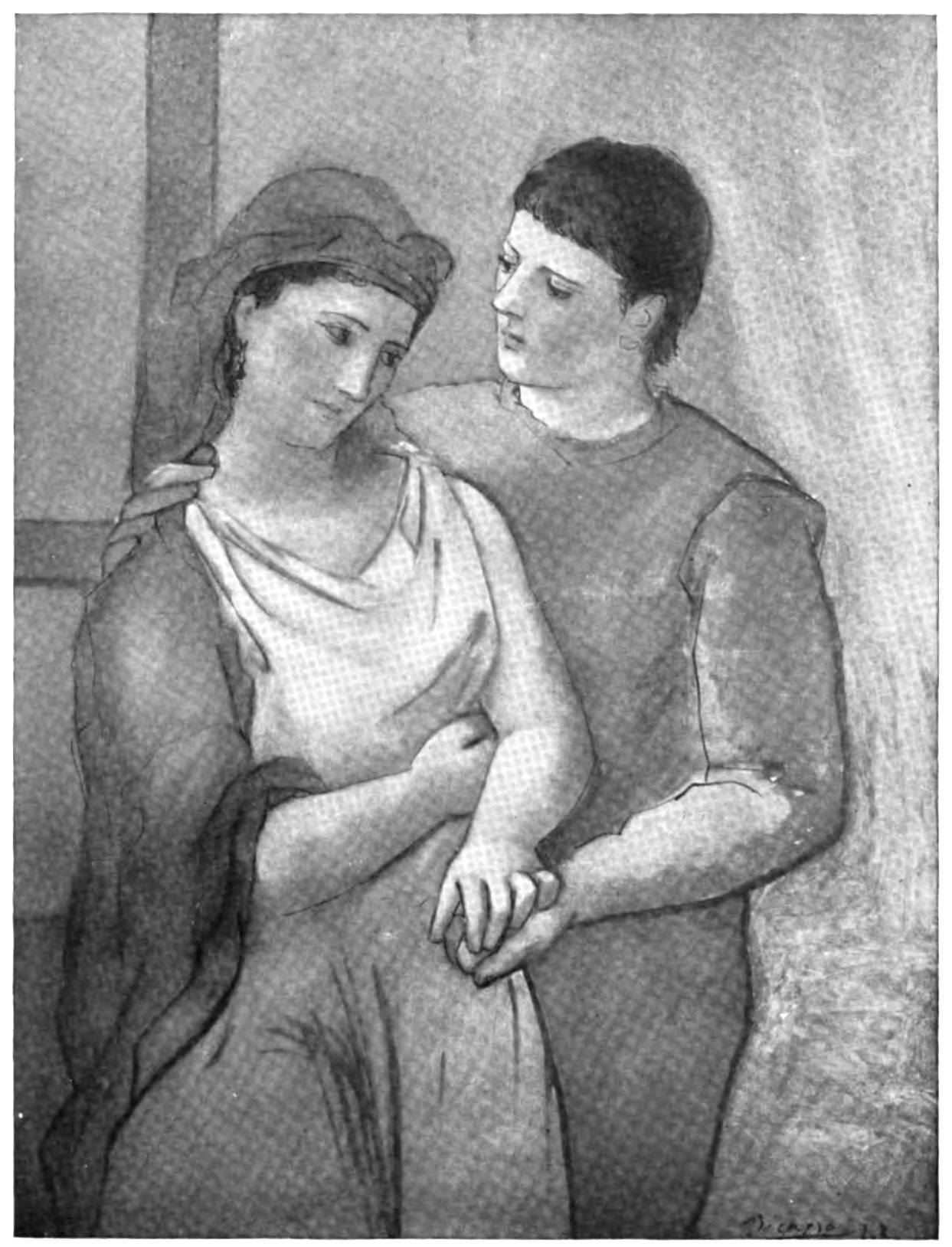

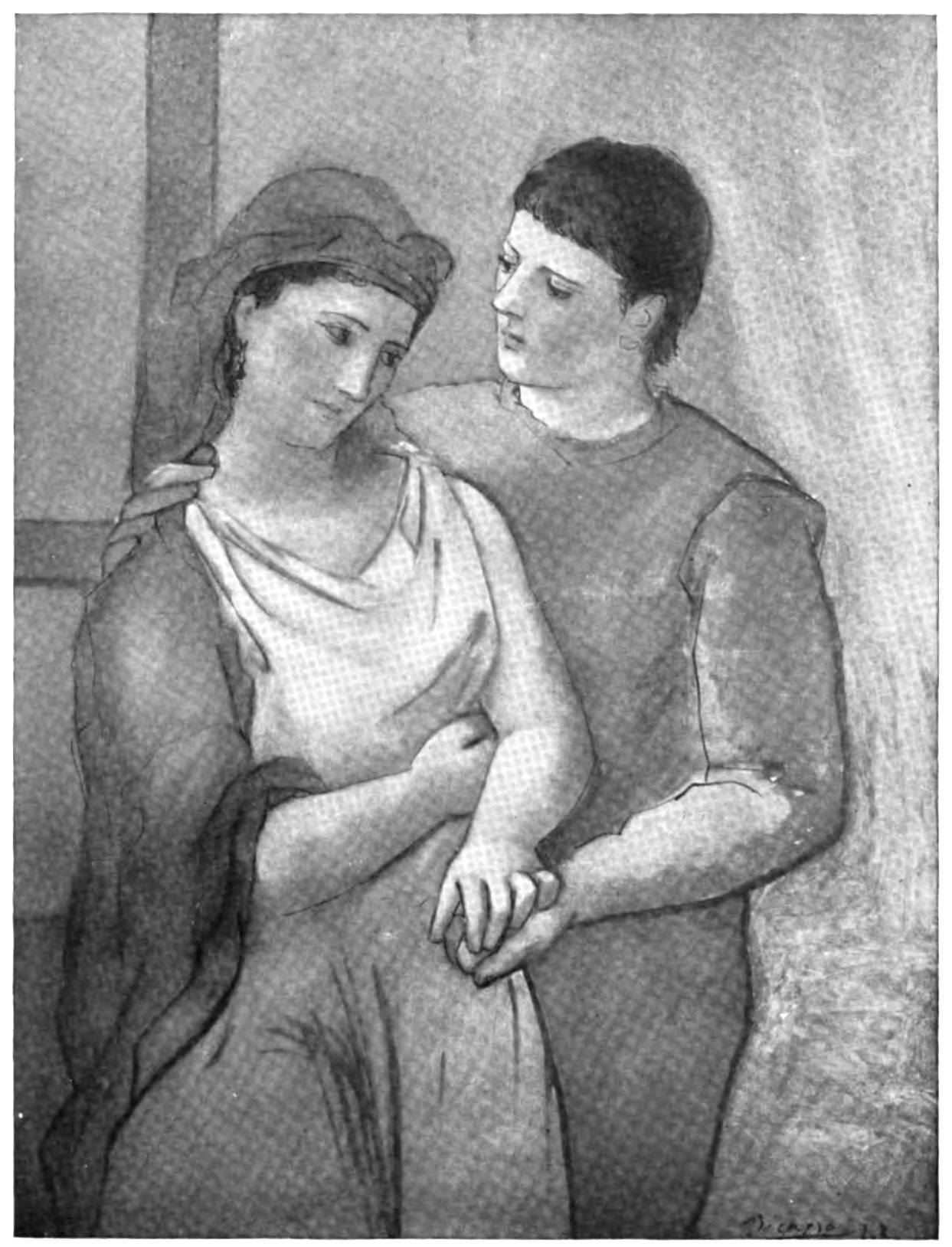

A PAINTING. By Pablo Picasso

More than that, I am convinced that if one is going to live fully and not shut oneself away from half of civilized existence, one must care for both. It is possible to do well enough with either, and much depends on how one derives pleasure from them. For no one imagines that a pedant or a half-wit, enjoying a classic or a piece of ragtime, is actually getting all that the subject affords. For an intelligent human being knows that one difference between himself and the animals is that he can “live in the mind”; to him there need be present no conflict between the great arts and the minor; he will see, in the end, that they minister to each other.

Most of the great works of art have reference to our time only indirectly—as they and we are related to eternity. And we require arts which specifically refer to our moment, which create the image of our lives. There are some twenty workers in literature, music, painting, sculpture, architecture, and the dance who are doing this for us now—and doing it in such a manner as to associate our modern existence with that extraordinary march of mankind which we like to call the progress of humanity. It is not enough. In addition to them—in addition, not in place of them—we must have arts which, we feel, are for ourselves alone, which no one before us could have cared for so much, which no one after us will wholly understand. The picture by Picasso could have been admired by an unprejudiced critic a thousand years ago, and will be a thousand years hence. We require, for nourishment, something fresh and transient. It is this which makes jazz so much the characteristic art of our time and Jolson a more typical figure than Chaplin, who also is outside of time. There must be ephemera. Let us see to it that they are good.

The characteristic of the great arts is high seriousness—it occurs in Mozart and Aristophanes and Rabelais and Molière as surely as in Æschylus and Racine. And the essence of the minor arts is high levity which existed in the commedia dell’arte and exists in Chaplin, which you find in the music of Berlin and Kern (not “funny” in any case). It is a question of exaltation, of carrying a given theme to the “high” point. The reference in a great work of art is to something more profound; and no trivial theme has ever required, or had, or been able to bear, a high seriousness in treatment. Avoiding the question of creative genius, what impresses us in a work of art is the intensity or the pressure with which the theme, emotion, sentiment, even “idea” is rendered. Assuming that a blow from the butt of a revolver is not exactly artistic presentation, that “effectiveness” is not the only criterion, we have the beginning of a criticism of æsthetics. We know that the method does count, the creativeness, the construction, the form. We know also that while the part of humanity which is fully civilized will always care for high seriousness, it will be quick to appreciate the high levity of the minor arts. There is no conflict. The battle is only against solemnity which is not high, against ill-rendered profundity, against the shoddy and the dull.

I have allowed myself to catalogue my preferences; it is possible to set the basis of them down in impersonal terms, in propositions:

That there is no opposition between the great and the lively arts.

That both are opposed in the spirit to the middle or bogus arts.

That the bogus arts are easier to appreciate, appeal to low and mixed emotions, and jeopardize the purity of both the great and the minor arts.

That except in a period when the major arts flourish with exceptional vigour, the lively arts are likely to be the most intelligent phenomena of their day.

That the lively arts as they exist in America to-day are entertaining, interesting, and important.

That with a few exceptions these same arts are more interesting to the adult cultivated intelligence than most of the things which pass for art in cultured society.

That there exists a “genteel tradition” about the arts which has prevented any just appreciation of the popular arts, and that these have therefore missed the corrective criticism given to the serious arts, receiving instead only abuse.

That therefore the pretentious intellectual is as much responsible as any one for what is actually absurd and vulgar in the lively arts.

That the simple practitioners and simple admirers of the lively arts being uncorrupted by the bogus preserve a sure instinct for what is artistic in America.

And now a detour around two of the most disagreeable words in the language: high- and low-brow. Pretense about these words and what they signify makes all understanding of the lively arts impossible. The discomfort and envy which make these words vague, ambiguous, and contemptuous need not concern us; for they represent a real distinction, two separate ways of apprehending the world, as if it were palpable to one and visible to the other. In connexion with the lively arts the distinction is clear and involves the third division, for the lively arts are created and admired chiefly by the class known as lowbrows, are patronized and, to an extent enjoyed, by the highbrows; and are treated as impostors and as contemptible vulgarisms by the middle class, those who invariably are ill at ease in the presence of great art until it has been approved by authority, those whom Dante rejected from heaven and hell alike, who blow neither hot nor cold, the Laodiceans.

Be damned to these last and all their tribe! There exists a small number of people who care intensely for the major and the minor arts and they are always being accused of “not caring really” for the lively ones, of pretending to care, or of running away from “the ancient wisdom and austere control” of Greek architecture or from the intense passion of Dante, the purity of Bach, the great totality of what humankind has created in art. It is claimed, and here the professional lowbrow agrees, that these others cannot care for the lively arts, unless they romanticize them and find things in them which aren’t there—at least not for the “real” patrons of those arts—those who observe them without thinking about them.

Aren’t they there, these secondary qualities? I take for example a sport instead of an art. Nothing about baseball interests me except the newspaper reports of the games, so I speak without prejudice. In the days of Babe Ruth I took the sun in the bleachers once and saw that heavy hitter do exactly what he had to do on his first appearance for the day—a straight, businesslike home run, much appreciated by the crowd, as any expert well-timed job is appreciated by Americans. The game that day went against the Yankees; they were two runs behind in the ninth, and with two men on base Ruth came up again. Again he hit a home run. And the crowd roaring its joy in victory exhaled two sighs, for the dramatic quality of the blow and for the lovely spiralling of the ball in its flight over the fence. “A beauty—a beauty”—you heard the expression a thousand times—and “He knows when to hit them.” They would have roared, too, if he had hit a single, which, muffed, would have brought in the winning run. But they would not have said, “a beauty”—and as far as I am concerned that is proof enough that the appreciation of æsthetic qualities is universal. It isn’t, thank Heaven, always put into words.

Take as another instance the fame of the Rath Brothers. They are acrobats who do difficult things, but there are others doing much the same sort of thing without approaching the réclame of these two. Their appearance of ease is a delight; there is no strain, no swelling muscles, no visible exploitation of strength. The Hellenic philosopher who held that the arrow shot from the bow is never in motion, but at rest from second to second at the succeeding points of its trajectory, might have seen some ancient forerunners of these athletes, for each of their movements seems at once a sculptured rest and a passage into another pose. And that is precisely the quality which vaudeville and revue audiences care for, and in a groping way recognize as distinctive and fine. They may think that Greeks have been candy-vendors since the beginning of time and that Marathon was a racecourse; but they know what they like.

I do not see, therefore, that recognition of these aspects of the gay arts can in any way detract from actual enjoyment—on the contrary it adds. You see Charlie about to throw a mop; the boss enters; without breaking the line of his movement Charlie swoops to the floor and begins to scrub. The first, the essential thing, is the fun in the dramatic turn; but what makes it funny is that there is no jerk, no break in the line—the two things are so interwoven that you cannot separate them. And if anyone were actually entirely unconscious of the line, the fun would be lost; it would be Ham and Bud, not Charlie, for such a spectator. The question is only to what degree one can be conscious of it—for I have known intellectuals who so reduced Charlie to angles that the angles no longer made them laugh. They have done the same with Massine and Nijinsky; they have followed the score so closely that they haven’t heard the music and they correspond exactly to the man who bets on the game and doesn’t see the play.

The life of the mind is supposed to be a terrible burden, ruining all the pleasures of the senses. This idea is carefully supported by “mental workers” (as they call themselves) and by the brainless. The truth is, of course, that when the mind isn’t afflicted by a desire to be superior, it does nothing but multiply all the pleasures, and the intelligent spectator, in all conscience, feels and experiences more than the dull one. To such a spectator the lively arts have a validity of their own. He cares for them for themselves, and their relation to the other arts does not matter. It is only because the place of the common arts in decent society is always being called into question that the answer needs to be given. I do not suppose that my answer is final; but I feel sure that it must be given, as mine is, from the outside.31

It happens that what we call folk music, folk dance, and the folk arts in general have only a precarious existence among us; the “reasons” are fairly obvious. And the popular substitutes for these arts are so much under our eyes and in our ears that we fail to recognize them as decent contributions to the richness and intensity of our lives. The result, strange as it may appear to devotees of culture, is that our major arts suffer. The poets, painters, composers who withdraw equally from the main stream of European tradition and from the untraditional natural expressions of America, have no sources of strength, no material to work with, no background against which they can see their shadows; they feel themselves disinherited of the future as well as the past.

At the same time the contempt we have for the lively arts hurts them as much as it hurts us. We have all heard of the “great artist of the speaking stage” who will not lower himself by appearing on the screen; as familiar is the vaudevillian who will call himself an artist and has hankerings for the legit; we have seen good dancers become bad actors, good black-face comedians develop alarming tendencies toward singing sentimental ballads in whisky-tenor voices, good comic-strip artists beginning to do bad book illustrations. The “step upward” is never in the direction of superior work, but toward a more rarefied acclaim. They are like a notable novelist who has for years tried unsuccessfully to write a failure, because he has only one standard of artistic success: popularity—but in reverse.

As these artists suffer under opprobrium and try to avoid it by touching the field of the faux bon, their work becomes more and more refined and genteel. The broadness, rough play, vitality, diminish gradually until a sort of Drama League seriousness and church-sociable good form are both satisfied. And all the more’s the pity, for the thinning out of our lives goes on from day to day and these lively arts are the only things which can keep us hard and robust and gay. In America, where there is no recognized upper class to please, no official academic requirements to meet, the one tradition of gentility is as lethal as all the conventions of European society, and unlike those of Europe our tradition provides no nourishment for the artist. It is negative all the way through.

In spite of gentility the lively arts have held to something a little richer and gayer than the polite ones. They haven’t dared to be frank, for a spurious sense of decency is backed by the police, and this limitation has hurt them; but it has made them sharp and clever by forcing their wit into deeper channels. There still exists a broadness in slap-stick comedy and in burlesque, and once in a while vast figures of Rabelaisian comedy occur. For the most part the lively arts are inhibited by the necessity to provide “nice clean fun for the whole family”—a regrettable, but inevitable penalty for their universal appeal. For myself, I should like to see a touch more of grossness and of license in these arts; it would be a sign that the blood hadn’t gone altogether pale, and that we can still roar cheerfully at dirty jokes, when they are funny.

What Europeans feel about American art is exactly the opposite of what they feel about American life. Our life is energetic, varied, constantly changing; our art is imitative, anæmic (exceptions in both cases being assumed). The explanation is that few Europeans see our lively arts, which are almost secret to us, like the mysteries of a cult. Here the energy of America does break out and finds artistic expression for itself. Here a wholly unrealistic, imaginative presentation of the way we think and feel is accomplished. No single artist has yet been great enough to do the whole thing—but together the minor artists of America have created the American art. And if we could for a moment stop wanting our artistic expression to be necessarily in the great arts—it will be that in time—we should gain infinitely.

Because, in the first place, the lively arts have never had criticism. The box-office is gross; it detects no errors, nor does it sufficiently encourage improvement. Nor does abuse help. There is good professional criticism in journals like Variety, The Billboard, and the moving-picture magazines—some of them. But the lively arts can bear the same continuous criticism which we give to the major, and if the criticism itself isn’t bogus there is no reason why these arts should become self-conscious in any pejorative sense. In the second place the lively arts which require little intellectual effort will more rapidly destroy the bogus than the major arts ever can. The close intimacy between high seriousness and high levity, the thing that brings together the extremes touching at the points of honesty and simplicity and intensity—will act like the convergence of two armies to squeeze out the bogus. And the moment we recognize in the lively arts our actual form of expression, we will derive from them the same satisfaction which people have always derived from an art which was relevant to their existence. The nature of that satisfaction is not easily described. One thing we know of it—that it is pure. And in the extraordinarily confused and chaotic world we live in we are becoming accustomed to demand one thing, if nothing else—that the elements presented to us however they are later confounded with others, shall be of the highest degree in their kind, of an impeccable purity.