CHAPTER XXVII

CORIOLANUS AND HIS MOTHER VETURIA

MANY legends are told of the wars which the Romans now waged with a fierce tribe named the Volscians.

None, perhaps, is so well known as the story I am going to tell you of Gaius Marcius, who was named Coriolanus.

Marcius was only a lad of seventeen years of age when he fought in the great battle of Lake Regillus. For his courage in saving the life of a comrade on the battlefield he was crowned with a wreath of oak leaves, as was the Roman custom.

The young lad loved his mother Veturia well. When the battle was over, his first thought was to hasten to show her the wreath that his valour had gained, for he had no greater joy than to please her.

When the Romans went to war with the Volscians, Marcius was with the army which was besieging Corioli, their capital town.

One day, the defenders of the city, seeing that part of the Roman army had withdrawn from the walls, determined to venture out to attack those soldiers who remained.

So fierce was their onslaught, that the Romans began to give way.

Marcius, who was some distance off, saw what had happened, and with only a few followers rushed to the aid of his comrades, at the same time calling in a loud voice to those who were retreating to follow him.

Encouraged by the young patrician, the Romans rallied, and dashing after Marcius, they soon forced the enemy to turn and fly back toward the shelter of their city.

The Romans pursued the Volscians until they reached the gates, but they did not dream of entering, for within the city were many more of the enemy. Already the walls were manned, and a deadly rain of arrows was descending among them.

But Marcius, crying that the gates were open, ‘Not so much to shelter the vanquished as to receive the conquerors,’ forced his way into the city.

With only a handful of men, he succeeded in keeping the gates of Corioli open, until the main body of the army arrived, when the city was taken without difficulty.

The soldiers said, as was indeed the truth, that it was Gaius Marcius who had taken the city.

When the war with the Volscians ended, the Consul wished to reward Marcius for this and many another courageous deed. So he ordered that of all the booty that had been taken in the war, the tenth part should be given to the brave young patrician. He himself gave to Marcius a noble horse, splendidly caparisoned.

But Marcius refused to receive more than his proper share of the booty. He begged, however, for one favour. It was that a Volscian who had shown him hospitality and was now a prisoner, might be set free.

Shouts of applause greeted Marcius when the soldiers heard his request.

When all was again quiet, the Consul said: ‘It is idle, fellow-soldiers, to force and obtrude those other gifts of ours on one who is unwilling to accept them. Let us therefore give him one of such a kind that he cannot well reject it. In memory of his conquest of the city of Corioli, let him henceforth be called Coriolanus.’

So it was that from this time Coriolanus was the name of the young soldier.

In Rome, as was usual after war, there was much misery, for the fields had been left unploughed, and no seed had been sown while the plebeians were away on the battlefield. Now the people were starving.

The Consuls sent to Etruria for food, and when it reached Rome it was divided among the people, but still there was not enough to satisfy their hunger.

While the people still cried for bread, the time to elect Consuls for the following year drew near.

Coriolanus was one of the candidates. He came to the Forum, clad in his white toga only, and drawing it aside he showed to the people the marks of the wounds he had received in fighting for his country.

But although at first they meant to elect Coriolanus, many of them remembered that he often spoke of their tribunes with bitter contempt. If he were Consul, he might try to do away with the tribunes altogether, and to whom then would the people be able to appeal against the oppression of the haughty patricians?

When the day came to elect the Consuls, the feeling against Coriolanus had grown so strong that he was rejected. This made him very angry with the plebeians, nor did he try to disguise his feelings.

Soon after the elections were over, large ships laden with corn reached Ostia. The senators were eager to feed the starving people, and as some of the corn was a gift, they were ready to give it to them without charging even a small sum.

But Coriolanus was indignant, and denounced in the Senate-house those who wished to treat the people so well. The plebeians had already grown more insolent than was fitting, owing to the favours bestowed upon them. ‘Before you feed them,’ said the haughty patrician, ‘let them give up their tribunes.’

When the plebeians learned what Coriolanus had said, their anger knew no bounds. They would have forced their way into the Senate-house and torn him to pieces, had not the tribunes protected him and calmed the fury of the people.

‘Do not kill him,’ said the tribunes, ‘for that will only harm your cause. We will accuse him of having broken the sacred laws, and you shall yourselves pronounce his sentence.’

But when the tribunes summoned Coriolanus to appear before them, he mocked both at them and at the people.

A patrician appear before the tribunes to be judged! That was to Coriolanus a foolish idea.

But although the patrician ignored the summons, the tribunes and the people met and declared that Coriolanus was banished from Rome.

Then Coriolanus was forced to leave the city. Hastening to the Volscians, he threw himself upon the mercy of their chief, Attius Tullius.

Tullius was willing to help the banished patrician to punish Rome, and soon an army, led by the chief and by Coriolanus, was on its way to the city. Town after town fell into the hands of the advancing army. At length it encamped only five miles from Rome.

The Senate, in alarm at the success of the Volscians, sent to beg for peace.

But Coriolanus sent back the Roman ambassadors, saying that unless all the towns taken from the Volscians in the last war were restored to them, peace would not be granted.

Such terms were scorned by the Senate, and it sent other ambassadors to beg for easier conditions. But Coriolanus refused even to see these messengers.

Then the priests, clad in their sacred robes, walked in solemn procession to the camp of the enemy, to try to appease the anger of the haughty patrician. But the efforts of the priests were vain.

Meanwhile, the matrons of Rome had been beseeching Jupiter to come to the aid of the city.

When the priests returned, having accomplished nothing, one of these matrons said: ‘We will go to Veturia and Volumnia and beseech them to go plead with Coriolanus. He cannot refuse to listen to his mother and his wife, for he loves them well.’

Veturia, who was stricken with grief that her son could betray his country into the hands of the enemy, needed no persuasion to go to speak with him.

Clad in black garments, she and Volumnia with her little children, followed by a band of Roman matrons set out for the camp of the enemy.

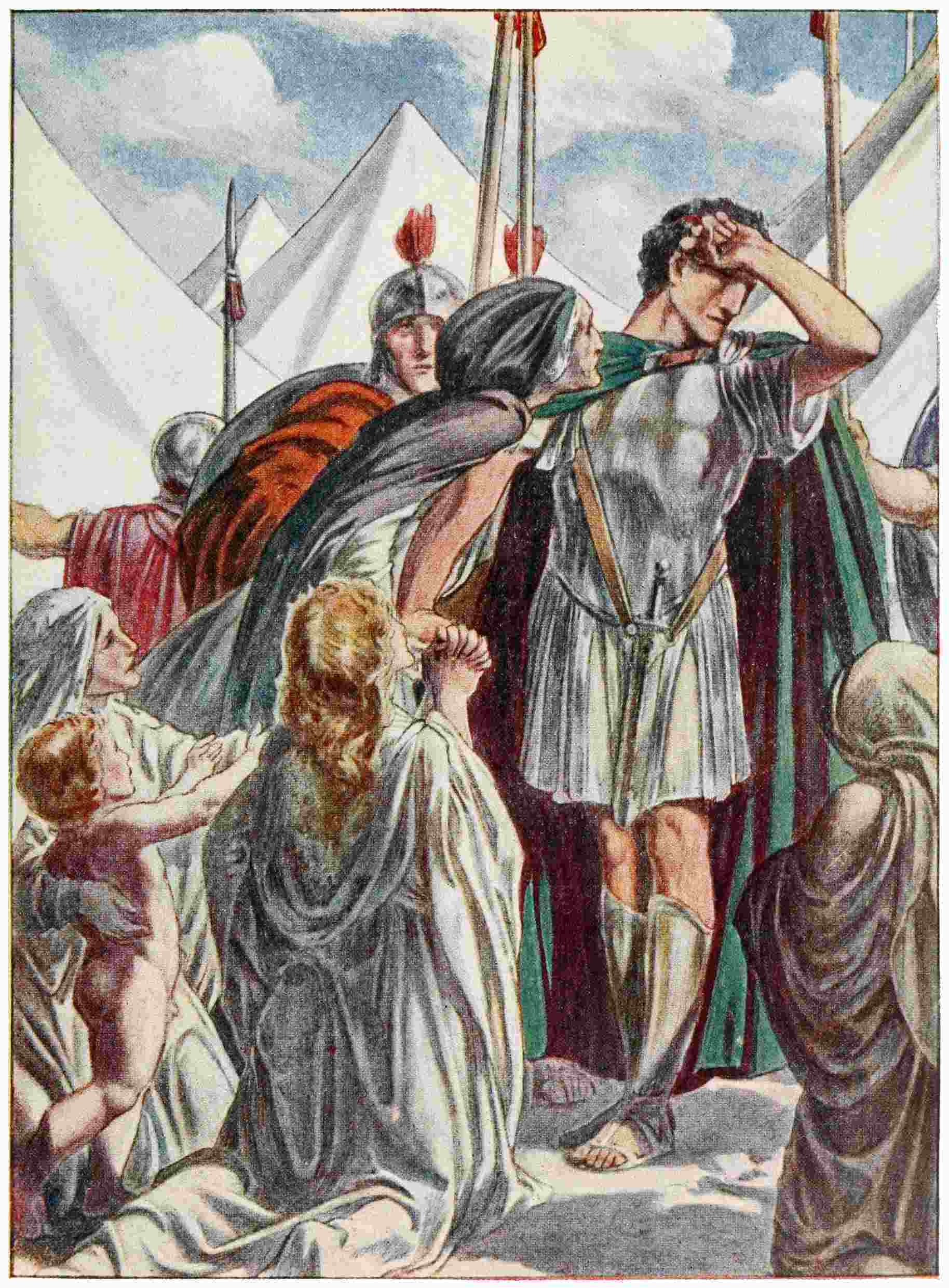

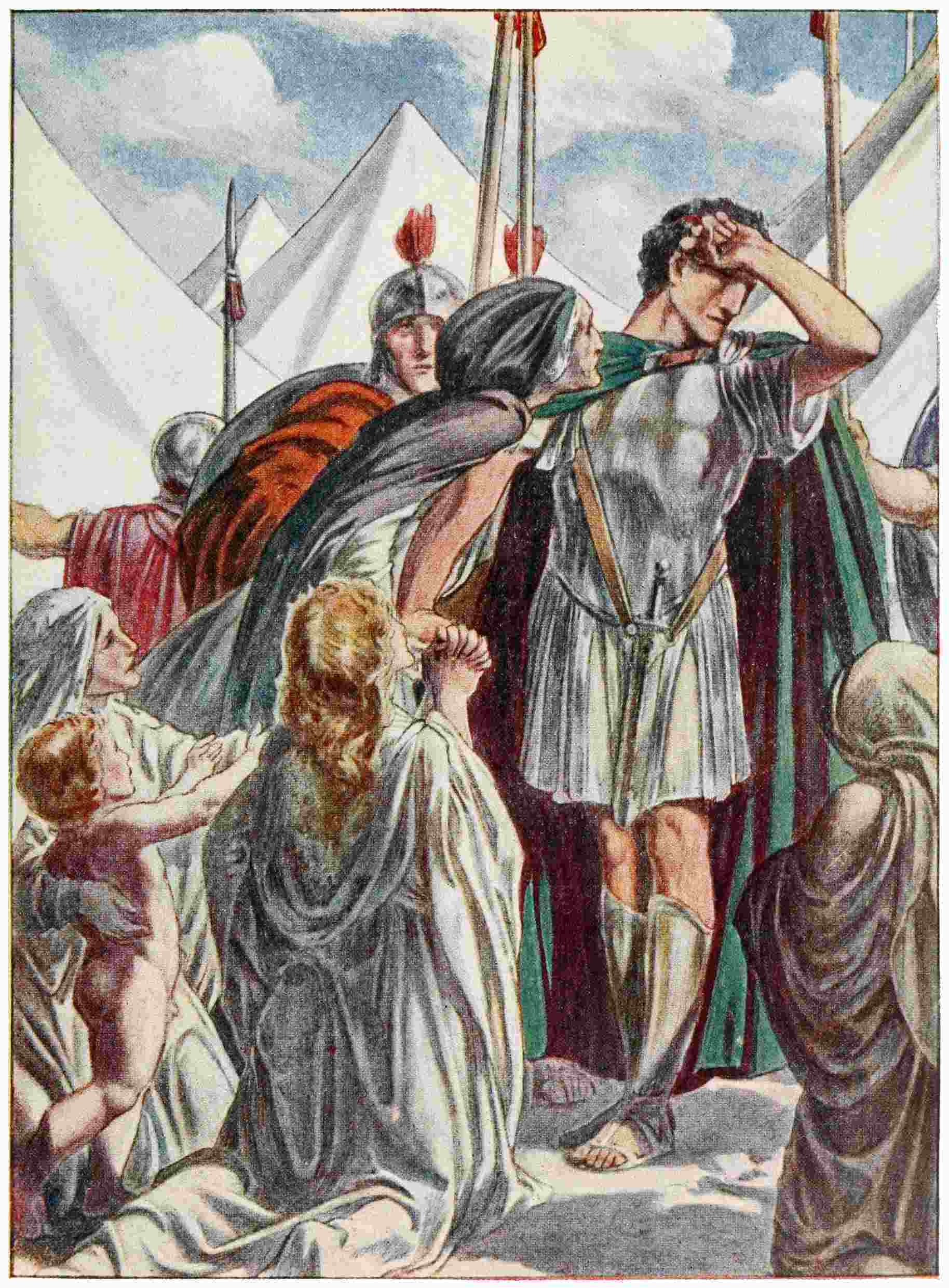

Coriolanus, when he caught sight of his mother, leaped from his seat, and running quickly toward her, would have kissed her, as was his wont.

But she, putting him aside, bade him first answer her question.

‘Am I the mother of Gaius Marcius,’ she asked reproachfully, ‘or a prisoner in the hands of the leader of the Volscians? Alas! had I not been a mother, my country had still been free.’ As his mother said these words, his wife and children fell at his knees and clung to him. His mother’s words did what nothing else had been able to do, for the proud patrician could not bear to listen to her reproaches.

With tears in his eyes he cried: ‘O my mother, thou hast saved Rome, but thou hast lost thy son.’

Then he led the Volscian army away from the city, and restored to the Romans the towns which the enemy had taken.

Some legends tell that the Volscians were so angry with Coriolanus for deserting them, that they slew him as a traitor; but others say that he lived in exile until he was an old man.

Weary of exile, he is said to have cried: ‘Only an old man knows how hard it is to live in a far country.’

“O my mother, thou hast saved Rome, but thou hast lost thy son.”