CHAPTER XXXVI

THE SACRED GEESE

ROME, when she heard of the defeat of Allia was stricken with terror. Her walls were left unguarded, her gates open, for the one thought of the citizens was flight.

And in truth, so fearful were they lest the Gauls should reach the city and find them still there, that they crowded out of the gates, across the bridge to the Janiculum.

Some few sacred images they stayed to bury, and the vestal virgins tarried to take with them the sacred fire which must not be allowed to die, but many of the most sacred treasures of Rome were left to perish by the hands of the barbarians.

So the city was left desolate, her gates open to the enemy. Only in the Capitol, the temple of the gods, a band of armed men kept guard, and with them stayed the priests, who refused to leave the sacred building, and the Senate.

No others were left in Rome save some old patricians, who long years before had been Consuls, and had led the legions of the Republic to many a hard-won battlefield.

These clad themselves in their richest robes, then, after praying to the gods, they walked to the Forum and seated themselves, each in his ivory chair, there to await what the gods should send.

Three days after the Battle of Allia, the Gauls, having feasted as was their custom after a victory, appeared before the city.

The gates were open, the walls unmanned, and within the city all was silent as the grave. Was it a trap? Did an ambush lie in wait? Thus the Gauls hesitated, questioning one another.

At length they ventured into the city—not a single citizen was to be seen. On through the desolate streets wandered the bewildered warriors, until at length they stood in the Forum.

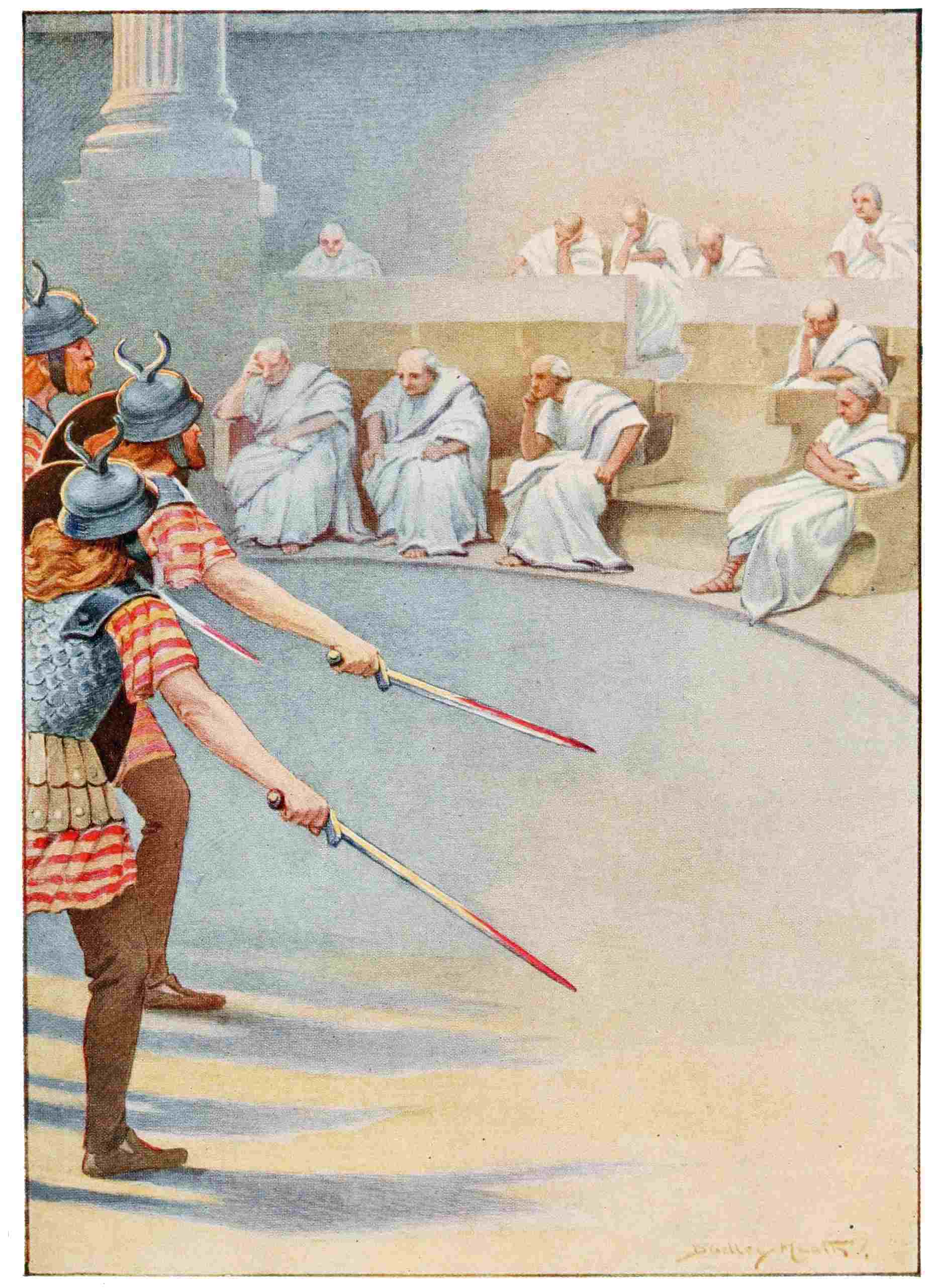

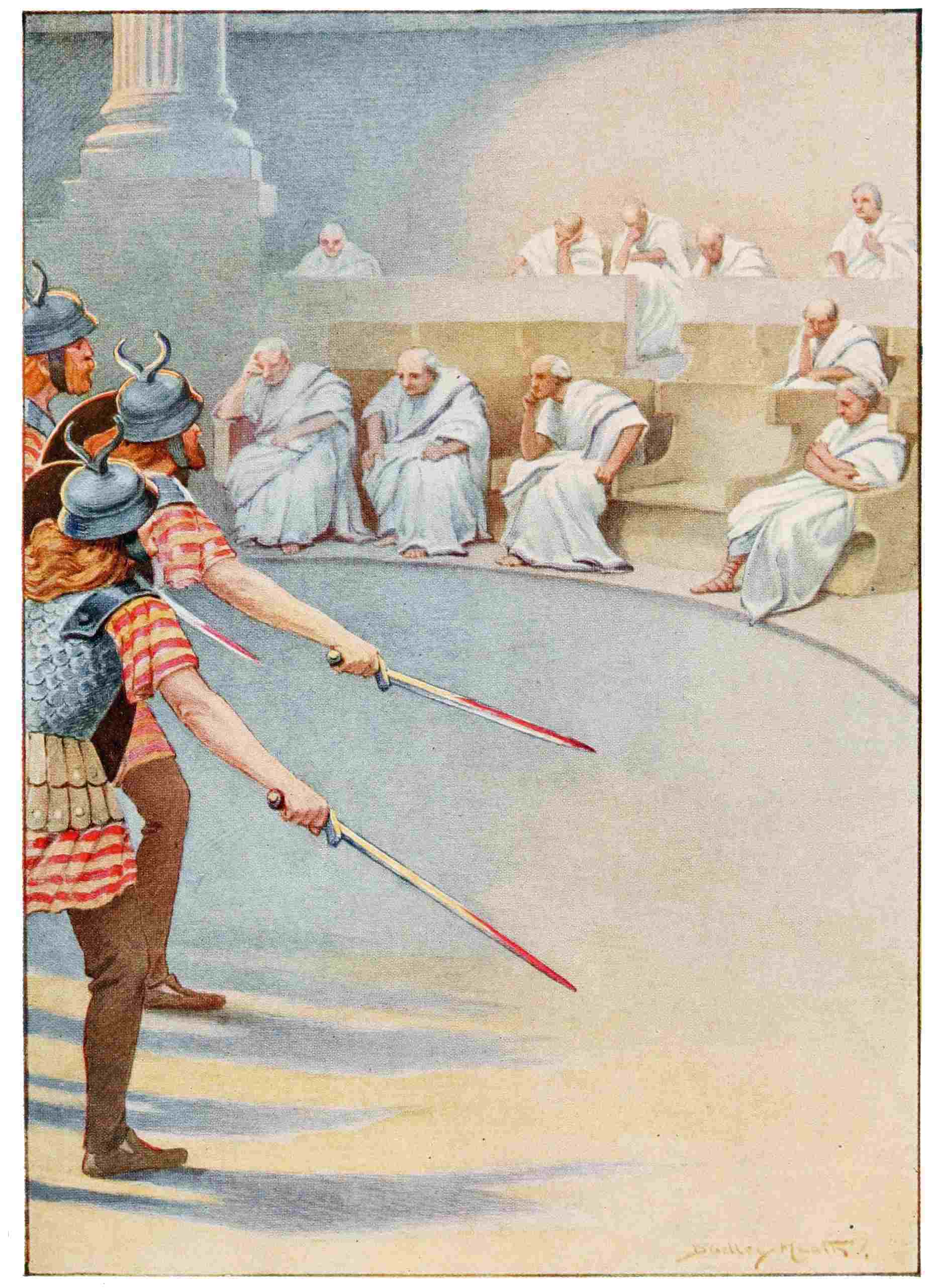

There, seated in chairs of ivory, silent and still as statues, sat a number of strange, venerable old men.

King Brennus himself came to the Forum to gaze at these still images of men, and was amazed to see them thus unmoved in his presence.

He noticed that ‘they neither rose at his coming, nor so much as changed colour or countenance, but remained without fear or concern, leaning upon their staves, and sitting quietly, looked at each other.’

For a long time the Gauls gazed in silence at the quiet figures. Then, one of the soldiers, bolder than the others, drew near to Papirius, stretched out his hand, and slowly stroked the long white beard of the old patrician.

This was more than Papirius could bear. He, a Roman senator, to be touched by a barbarian! Quick as thought he raised his staff and struck the Gaul a blow.

The strange, silent images were alive then! They could move!

Swiftly the barbarian drew his sword, and a moment later Papirius fell from his ivory chair, wounded to death.

No longer awed by the silent images, the Gauls now fell upon the other patricians and killed them too. Then for days they sacked the city, and at length burned it to the ground, angry that the Capitol was held against them.

The Capitol stood on a hill, steep and impossible to scale, save at one point.

Seated in chairs of ivory, sat a number of strange, venerable old men.

Again and again the Gauls tried to storm this one approach, but the brave defenders drove them back, killing some of their number. Then the Gauls determined to besiege the Capitol, but days and weeks passed, and still they seemed no more likely to take it than before. And now their provisions were beginning to run short.

Meanwhile, the Roman soldiers who had fled from Allia and taken refuge in Veii, began to be ashamed of themselves. Surely they ought to go to the help of their comrades who were so manfully holding the Capitol. If they had but a leader they would go.

Then all at once they remembered Camillus, who was still in exile. They would ask him to come back and lead them as of old to victory.

So they sent to beg Camillus to come to Veii and take command of the soldiers. But Camillus refused to come unless the Senate recalled him and asked him to deliver Rome.

At first it seemed that there was no way to reach the Senate. It was shut up in the Capitol. But a young soldier, named Cominius, hoping to retrieve the disgrace of his flight from Allia, offered to try to scale the rock and reach the citadel.

Disguising himself as a poor man, and carrying corks under his old clothes, he reached the Tiber as it was growing dark. The bridge, as he had expected, was guarded by the Gauls. To cross it was impossible.

So, taking off his clothes, he tied them on to his head, and laying the corks he had brought in the river, he swam with their help safely across and slipped unnoticed into the city.

Cominius, fortunately, was light and agile. He actually succeeded in scaling the rock on which the Capitol was built, as only a bold and skilful climber could. When he reached the summit in safety he called to the astonished guards and begged to be taken to the Senate.

It was pleased to see the brave youth, and after listening to his tale at once bade Cominius return and let Camillus know that Rome not only recalled him from exile, but appointed him Dictator. So Cominius hastened back to Veii with the good news, and because the soldiers were eager to fight, messengers were sent in hot haste to Camillus to tell him the decision of the Senate, and to bring him back to Veii.

Soon Camillus had twenty thousand men ready to follow him to Rome.

Meanwhile the Capitol was all but taken by the Gauls.

The morning after Cominius had clambered down the cliff, the barbarians noticed that the shrubs had been crushed, that bushes had had their branches torn, that the soil had been loosened on the side of the rock.

It was clear that some one had either climbed up to the Capitol, or had come down the terrible descent. And if that was possible, why should not they climb the cliff, and at last capture the Capitol?

So when night had come, the Gauls began their dangerous task. Up and up they climbed as noiselessly as might be, up and up, until they had nearly reached the top.

At the summit there was no wall, no sentinel. Even the watchdogs heard no sound and slept on undisturbed.

Close to the top of the rock, however, stood the temple of Jupiter, Juno, and Minerva, the three guardian deities of Rome. Without the temple, geese, sacred to Juno, had their home. Although the defenders of the Capitol were starving, yet they never dreamed of touching the birds that were sacred to the goddess, ‘which thing proved their salvation.’

Up and up climbed the Gauls, and no one heard them as they drew near to the summit of the rock, no one save the sacred geese. They, divine birds as they were, began to cackle and to flap their wings, and to make as much noise as geese can make.

Manlius, the captain of the guard, who slept near the temple, awoke startled to hear the din caused by the sacred birds. Springing swiftly from the couch on which he had lain wrapped in his military cloak, he seized his arms and ran to the top of the cliff. As he ran he shouted to his men to follow as quickly as they could.

As Manlius reached the edge of the rock, lo, the face of a Gaul peered at him over the summit.

The Roman was but just in time. Dashing his shield at the enemy, he hurled him down the cliff, and he, as he fell, knocked against those who were behind, so that they also were carried down the face of the rock, which they had climbed with so much difficulty. Thus the Capitol was saved by the sacred geese.

The defenders of the citadel were grateful to Manlius for acting so promptly, and although they were all suffering from hunger, each one agreed to give him, from his own slender store, one day’s allowance of food. This consisted of half a pound of corn and a measure holding five ounces of wine.

At length a day came when the brave folk in the Capitol must either die of starvation or surrender. So the senators sent to King Brennus and offered to pay him a large sum of money if he would raise the siege.

As the Gauls too were suffering from famine, the king was willing to accept a ransom, but he demanded the large sum of one thousand pounds of gold.

Only by borrowing treasures from the temple, and receivings gifts of golden ornaments from Roman matrons, could the sum be found.

In bitterness of spirit the Romans went down to the Forum on the day appointed, and began to lay their treasures on the scales.

Suddenly they noticed that the weights which the barbarians were using on their scales, were false.

But when they complained, the king threw his sword into the scale, crying scornfully, ‘Væ Victis,’ ‘Woe to the Conquered.’

At that moment, Rome was saved from the shame of paying a ransom, for Camillus with his army marched into the Forum.

As Dictator, the supreme power was his, and he had the right to forbid even what the Senate had allowed.

He looked at the gold ornaments lying in the scales, and bade the Romans take them back, for, said Camillus proudly, ‘It is usual with Romans to pay their debts, not in gold, but in iron.’ By these words the Dictator meant that the Romans used their weapons to settle their quarrels.

Then, forcing the Gauls out of the city which they had ruined, Camillus and his army fought so fiercely against their enemy that not a single man was left alive to tell the tidings to his countrymen.

King Brennus himself was slain, and as he fell he heard the Romans shout in triumph the words he himself had so lately used, ‘Væ Victis,’ ‘Woe to the conquered.’