CHAPTER XLI

THE DREAM OF THE TWO CONSULS

THE Samnites were a rough and hardy race of warriors, whose homes were among the mountains of the Apennines.

In 343 B.C. they determined to wrest Campania, in the south of Italy, from the Romans.

The wars of the Samnites lasted for many long years, and when at length Rome conquered, she was mistress of Italy. But before she was victorious, the first, second, and third Samnite wars had been fought and won.

Of the first Samnite war little is known, save that it lasted for three years, and that the Romans won three battles.

During this first war, however, the Latins, who had allied themselves with Rome, revolted. They wished to be given the full rights of Roman citizens, and they demanded that one Consul, as well as half the members of the Senate should be Latins. Nor was this all. For they refused to be content unless Latium and Rome were henceforth counted as one Republic.

The Romans did not for a moment dream of granting such ambitious demands. Indeed, they resolved to punish the Latins for their presumption in making such large requests.

So they went to war and fought, until the Latins lost their last stronghold and were forced again to submit to Rome.

The Latins had gained little by provoking their former allies, for while some Latin cities were granted the rights of Roman citizens, all were forced to send soldiers to the Roman army.

Two famous stories are told of the war with the Latins.

The armies had encamped near to each other on the plain of Capua, in the south of Italy.

Manlius Torquatus was one of the Consuls, and he, with his colleague, had given strict orders that no soldier was to engage in single combat.

But the son of Torquatus chanced to be challenged by one of the enemy, and the temptation to fight was more than the young man could stand.

Was he victorious, what glory he would win! Was he beaten, he could but die! So, despite the strict order of the Consuls, young Manlius accepted the challenge.

Groups of Roman and Latin soldiers watched the combat with the keenest interest, and when at length, after a gallant fight, Manlius slew his opponent, a shout of triumph arose from his comrades. But the Latins looked on, sullen and ashamed, while their champion was stripped of his arms.

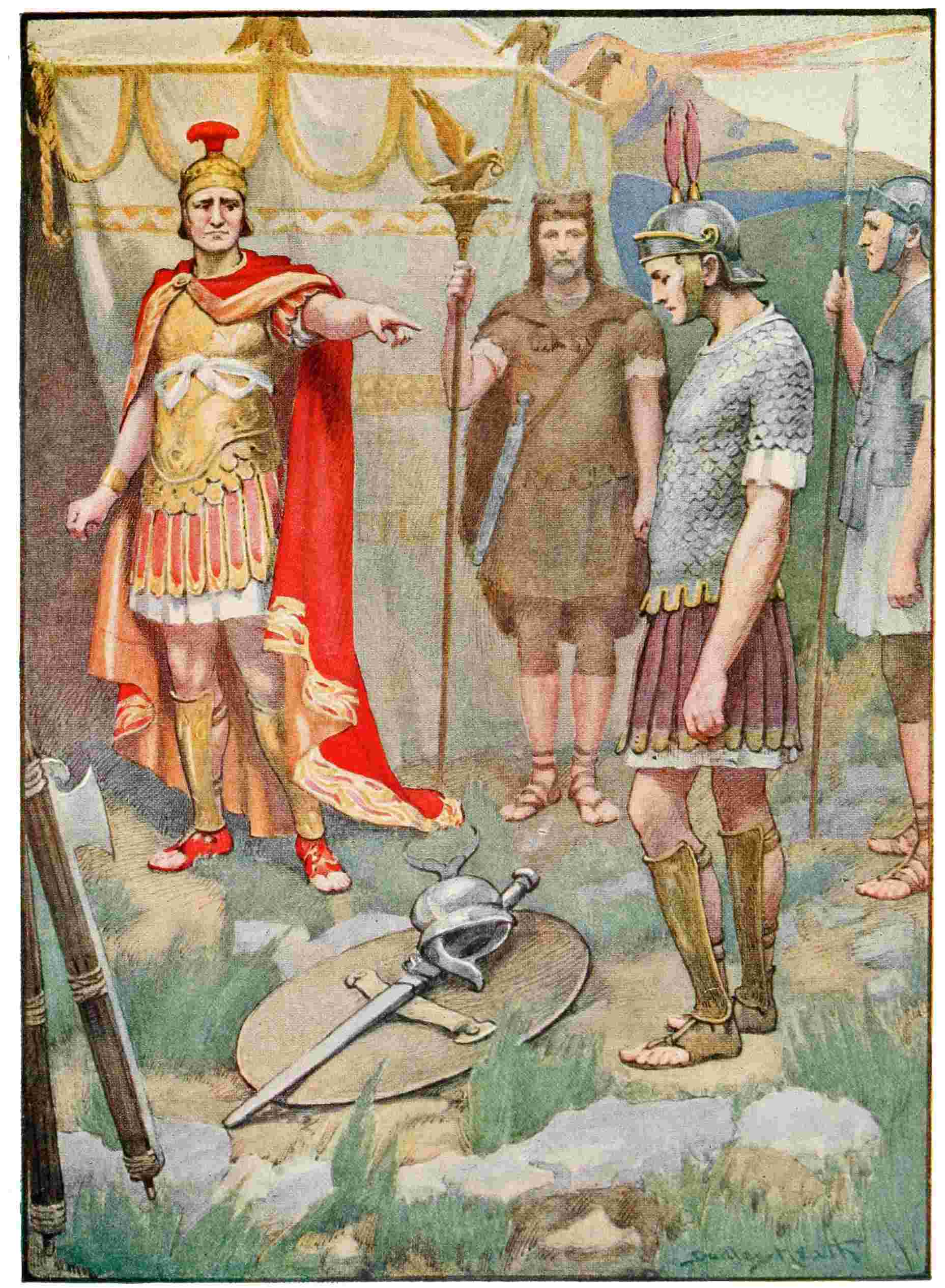

Flushed with victory, and thinking that his father would forgive his disobedience, the youth hastened to the tent of Torquatus, and laid the arms he had taken from his foe at his father’s feet.

But discipline was dear to the Consul’s heart, and he did not greet his son as he entered the tent, but turned coldly away from him. Had it been any other who had disobeyed, punishment swift and sharp would have descended on the culprit.

It made Torquatus angry to think that he should dream even for a moment of being more merciful to his own son than to another. He loved discipline, but he loved his son as well. So it was with a mighty effort that he resolved that, although it was his own son who had transgressed, punishment swift and sharp should be inflicted on him.

The youth laid the arms he had taken from his foe at his father’s feet.

Cold and stern, the Consul’s voice rang out, bidding the soldiers assemble in front of his tent, and there, before them all, he ordered that his son should be beheaded.

No one dared to dispute the order of the Consul, and the soldiers looked on in horror while their brave young comrade was put to death because of his disobedience.

The soldiers hated Torquatus for his severity, and never forgot it. But if they hated, they also feared, and never again were his commands disobeyed.

The second story is about a terrible battle that was fought close to Mount Vesuvius.

It was the night before the battle that the two Consuls, Torquatus and Decius Mus, both dreamed the same dream.

A man taller than any mortal appeared to each of the Consuls, and warned him that in the battle which was to be fought, both sides must suffer, one losing its leader, the other its whole army.

In the morning, when the Consuls found that each had dreamed exactly the same dream, they determined to appeal to the gods. Even as their dreams were alike, so also was the answer each received.

‘The gods of the dead, and earth, the mother of all, claim as their victim the general of one party and the army of the other.’

At all costs the Roman army must be saved. Of that neither Consul had any doubt. Nor did they shrink when they realised that to save the army one of them must perish.

So Manlius and Decius Mus agreed that the one whose legions should first give way before the enemy should give himself up to the gods of the dead.

When the battle was raging most fiercely, the right wing of the Latins compelled one of the Roman divisions to give way. The leader of the division was Decius Mus.

Without a murmur, the Consul prepared to fulfil the agreement he had made with Torquatus. By doing so he was sure that he would save the army from destruction.

Turning to a priest who was on the battlefield, he begged to be told how best to devote himself to the gods.

Then the priest bade Decius Mus take the toga that he wore as Consul, but which was not usually seen on the battlefield, and wrap it round his head, holding it close to his face with one of his hands. His feet the Consul placed on a javelin, and then, as the priest bade, he prayed to the god of the dead.

‘God of the dead, I humbly beseech you, I crave and doubt not to receive this grace from you, that you prosper the people of Rome with all might and victory; and that you visit the enemies of the people of Rome ... with terror, with dismay, and with death.

‘And, according to these words which I have spoken, so do I now, on behalf of the Commonwealth of the Roman people ... devote the legions and the foreign aids of our enemies, along with myself, to the god of the dead and to the grave.’

When he had prayed, Decius Mus sent his lictors to tell Manlius what he was about to do.

Then, with his toga wrapped across his face, the noble Roman leaped upon his horse, and fully armed, plunged into the midst of the Latin army and was slain.

Inspired by the courage of Decius Mus, and knowing that the vengeance of the gods would now fall upon their enemies, the Romans fought with fresh courage.

At first the Latins were dismayed and driven backward. But they soon rallied, and fought so fiercely that it seemed as though the sacrifice of the Consul had been in vain.

But just as the Romans were beginning to give way, Manlius with a band of veterans rushed to their aid, and with loud cheers dashed upon the enemy.

The Latins, already weary, were not able to withstand this new shock. So the Romans were soon victorious, and slaughtered or took prisoners nearly a fourth part of the Latin army.

Torquatus now returned to Rome, expecting to receive a great triumph. But the citizens looked on his procession in silence and dislike, for he had come back from battle without his colleague.

In this the Romans were unjust to Torquatus, for had his legions been the first to flinch before the enemy, he would have faced death as bravely as did Decius Mus.