THE STORY OF THE GREEKS.

I. EARLY INHABITANTS OF GREECE.

Although Greece (or Hel´las) is only half as large as the State of New York, it holds a very important place in the history of the world. It is situated in the southern part of Europe, cut off from the rest of the continent by a chain of high mountains which form a great wall on the north. It is surrounded on nearly all sides by the blue waters of the Med-it-er-ra´ne-an Sea, which stretch so far inland that it is said no part of the country is forty miles from the sea, or ten miles from the hills. Thus shut in by sea and mountains, it forms a little territory by itself, and it was the home of a noted people.

The history of Greece goes back to the time when people did not know how to write, and kept no record of what was happening around them. For a long while the stories told by parents to their children were the only information which could be had about the country and its former inhabitants; and these stories, slightly changed by every new teller, grew more and more extraordinary as time passed. At last they were so changed that no one could tell where the truth ended and fancy began.

The beginning of Greek history is therefore like a fairy tale; and while much of it cannot, of course, be true, it is the only information we have about the early Greeks. It is these strange fireside stories, which used to amuse Greek children so many years ago, that you are first going to hear.

About two thousand years before the birth of Christ, in the days when Isaac wanted to go down into Egypt, Greece was inhabited by a savage race of men called the Pe-las´gi-ans. They lived in the forests, or in caves hollowed out of the mountain side, and hunted wild beasts with great clubs and stone-tipped arrows and spears. They were so rude and wild that they ate nothing but raw meat, berries, and the roots which they dug up with sharp stones or even with their hands.

For clothing, the Pelasgians used the skins of the beasts they had killed; and to protect themselves against other savages, they gathered together in families or tribes, each having a chief who led in war and in the chase.

There were other far more civilized nations in those days. Among these were the E-gyp´tians, who lived in Africa. They had long known the use of fire, had good tools, and were much further advanced than the Pelasgians. They had learned not only to build houses, but to erect the most wonderful monuments in the world,—the Pyr´a-mids, of which you have no doubt heard.

In Egypt there were at that time a number of learned men. They were acquainted with many of the arts and sciences, and recorded all they knew in a peculiar writing of their own invention. Their neighbors, the Phœ-ni´-cians, whose land also bordered on the Mediterranean Sea, were quite civilized too; and as both of these nations had ships, they soon began to sail all around that great inland sea.

As they had no compass, the Egyptian and Phœnician sailors did not venture out of sight of land. They first sailed along the shore, and then to the islands which they could see far out on the blue waters.

When they had come to one island, they could see another still farther on; for, as you will see on any map, the Mediterranean Sea, between Greece and Asia, is dotted with islands, which look like stepping-stones going from one coast to the other.

Advancing thus carefully, the Egyptians and Phœnicians finally came to Greece, where they made settlements, and began to teach the Pelasgians many useful and important things.

II. THE DELUGE OF OGYGES.

The first Egyptian who thus settled in Greece was a prince called In´a-chus. Landing in that country, which has a most delightful climate, he taught the Pelasgians how to make fire and how to cook their meat. He also showed them how to build comfortable homes by piling up stones one on top of another, much in the same way as the farmer makes the stone walls around his fields.

The Pelasgians were intelligent, although so uncivilized; and they soon learned to build these walls higher, in order to keep the wild beasts away from their homes. Then, when they had learned the use of bronze and iron tools, they cut the stones into huge blocks of regular shape.

These stone blocks were piled one upon another so cleverly that some of the walls are still standing, although no mortar was used to hold the stones together. Such was the strength of the Pelasgians, that they raised huge blocks to great heights, and made walls which their descendants declared must have been built by giants.

As the Greeks called their giants Cy´clops, which means "round-eyed," they soon called these walls Cy-clo-pe´an; and, in pointing them out to their children, they told strange tales of the great giants who had built them, and always added that these huge builders had but one eye, which was in the middle of the forehead.

Some time after Inachus the Egyptian had thus taught the Pelasgians the art of building, and had founded a city called Ar´gos, there came a terrible earthquake. The ground under the people's feet heaved and cracked, the mountains shook, the waters flooded the dry land, and the people fled in terror to the hills.

In spite of the speed with which they ran, the waters soon overtook them. Many of the Pelasgians were thus drowned, while their terrified companions ran faster and faster up the mountain, nor stopped to rest until they were quite safe.

Looking down upon the plains where they had once lived, they saw them all covered with water. They were now forced to build new homes; but when the waters little by little sank into the ground, or flowed back into the sea, they were very glad to find that some of their thickest walls had resisted the earthquake and flood, and were still standing firm.

The memory of the earthquake and flood was very clear, however. The poor Pelasgians could not forget their terror and the sudden death of so many friends, and they often talked about that horrible time. As this flood occurred in the days when Og´y-ges was king, it has generally been linked to his name, and called the Deluge (or flood) of Ogyges.

III. THE FOUNDING OF MANY IMPORTANT CITIES.

Some time after Inachus had built Argos, another Egyptian prince came to settle in Greece. His name was Ce´crops, and, as he came to Greece after the Deluge of Ogyges, he found very few inhabitants left. He landed, and decided to build a city on a promontory northeast of Argos. Then he invited all the Pelasgians who had not been drowned in the flood to join him.

The Pelasgians, glad to find such a wise leader, gathered around him, and they soon learned to plow the fields and to sow wheat. Under Cecrops' orders they also planted olive trees and vines, and learned how to press the oil from the olives and the wine from the grapes. Cecrops taught them how to harness their oxen; and before long the women began to spin the wool of their sheep, and to weave it into rough woolen garments, which were used for clothing, instead of the skins of wild beasts.

After building several small towns in At´ti-ca, Cecrops founded a larger one, which was at first called Ce-cro´pi-a in honor of himself. This name, however, was soon changed to Ath´ens to please A-the´ne (or Mi-ner´va), a goddess whom the people worshiped, and who was said to watch over the welfare of this her favorite city.

When Cecrops died, he was followed by other princes, who continued teaching the people many useful things, such as the training and harnessing of horses, the building of carts, and the proper way of harvesting grain. One prince even showed them how to make beehives, and how to use the honey as an article of food.

As the mountain sides in Greece are covered with a carpet of wild, sweet-smelling herbs and flowers, the Greek honey is very good; and people say that the best honey in the world is made by the bees on Mount Hy-met´tus, near Athens, where they gather their golden store all summer long.

Shortly after the building of Athens, a Phœnician colony, led by Cad´mus, settled a neighboring part of the country, called Bœ-o´tia, where they founded the city which was later known as Thebes. Cadmus also taught the people many useful things, among others the art of trade (or commerce) and that of navigation (the building and using of ships); but, best of all, he brought the alphabet to Greece, and showed the people how to express their thoughts in writing.

Almost at the same time that Cadmus founded Thebes, an Egyptian called Dan´a-us came to Greece, and settled a colony on the same spot where that of Inachus had once been. The new Argos rose on the same place as the old; and the country around it, called Ar´go-lis, was separated from Bœotia and Attica only by a long narrow strip of land, which was known as the Isthmus of Cor´-inth.

Danaus not only showed the Pelasgians all the useful arts which Cadmus and Cecrops had taught, but also helped them to build ships like that in which he had come to Greece. He also founded religious festivals or games in honor of the harvest goddess, De-me´ter. The women were invited to these games, and they only were allowed to bear torches in the public processions, where they sang hymns in honor of the goddess.

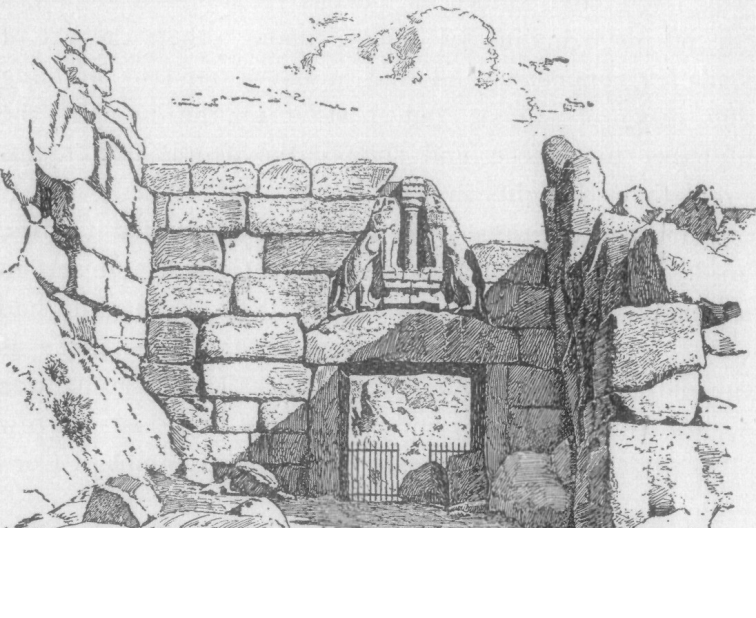

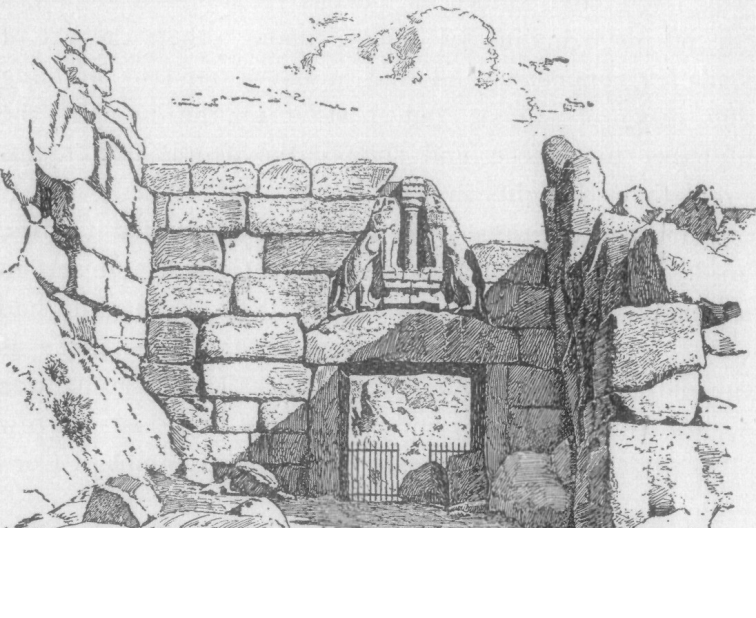

The descendants of Danaus long ruled over the land; and one member of his family, Per´seus, built the town of My-ce´næ on a spot where many of the Pelasgian stone walls can still be seen.

The Pelasgians who joined this young hero helped him to build great walls all around his town. These were provided with massive gateways and tall towers, from which the soldiers could overlook the whole country, and see the approach of an enemy from afar.

The Lion Gate, Mycenæ.

This same people built tombs for some of the ancient kings, and many treasure and store houses. These buildings, buried under earth and rubbish, were uncovered a few years ago. In the tombs were found swords, spears, and remains of ancient armor, gold ornaments, ancient pieces of pottery, human bones, and, strangest of all, thin masks of pure gold, which covered the faces of some of the dead.

Thus you see, the Pelasgians little by little joined the new colonies which came to take possession of the land, and founded little states or countries of their own, each governed by its own king, and obeying its own laws.

IV. STORY OF DEUCALION.

The Greeks used to tell their children that Deu-ca´li-on, the leader of the Thes-sa´li-ans, was a descendant of the gods, for each part of the country claimed that its first great man was the son of a god. It was under the reign of Deucalion that another flood took place. This was even more terrible than that of Ogyges; and all the people of the neighborhood fled in haste to the high mountains north of Thes´sa- ly, where they were kindly received by Deucalion.

When all danger was over, and the waters began to recede, they followed their leader down into the plains again. This soon gave rise to a wonderful story, which you will often hear. It was said that Deucalion and his wife Pyr´rha were the only people left alive after the flood. When the waters had all gone, they went down the mountain, and found that the temple at Del´phi, where they worshiped their gods, was still standing unharmed. They entered, and, kneeling before the altar, prayed for help.

A mysterious voice then bade them go down the mountain, throwing their mother's bones behind them. They were very much troubled when they heard this, until Deucalion said that a voice from heaven could not have meant them to do any harm. In thinking over the real meaning of the words he had heard, he told his wife, that, as the Earth is the mother of all creatures, her bones must mean the stones.

Deucalion and Pyrrha, therefore, went slowly down the mountain, throwing the stones behind them. The Greeks used to tell that a sturdy race of men sprang up from the stones cast by Deucalion, while beautiful women came from those cast by Pyrrha.

The country was soon peopled by the children of these men, who always proudly declared that the story was true, and that they sprang from the race which owed its birth to this great miracle. Deucalion reigned over this people as long as he lived; and when he died, his two sons, Am-phic´ty-on and Hel´len, became kings in his stead. The former staid in Thessaly; and, hearing that some barbarians called Thra ´cians were about to come over the mountains and drive his people away, he called the chiefs of all the different states to a council, to ask their advice about the best means of defense. All the chiefs obeyed the summons, and met at a place in Thessaly where the mountains approach the sea so closely as to leave but a narrow pass between. In the pass are hot springs, and so it was called Ther-mop´y-læ, or the Hot Gateway.

The chiefs thus gathered together called this assembly the Am-phic-ty-on´ic Council, in honor of Amphictyon. After making plans to drive back the Thracians, they decided to meet once a year, either at Thermopylæ or at the temple at Delphi, to talk over all important matters.

V. STORY OF DÆDALUS AND ICARUS.

Hellen, Deucalion's second son, finding Thessaly too small to give homes to all the people, went southward with a band of hardy followers, and settled in another part of the country which we call Greece, but which was then, in honor of him, called Hellas, while his people were called Hel-le´nes, or subjects of Hellen.

When Hellen died, he left his kingdom to his three sons, Do´rus, Æ´o-lus, and Xu´thus. Instead of dividing their father's lands fairly, the eldest two sons quarreled with the youngest, and finally drove him away. Homeless and poor, Xuthus now went to Athens, where he was warmly welcomed by the king, who not only treated him very kindly, but also gave him his daughter in marriage, and promised that he should inherit the throne.

This promise was duly kept, and Xuthus the exile ruled over Athens. When he died, he left the crown to his sons, I´on and A-chæ´us.

As the A-the´ni-ans had gradually increased in number until their territory was too small to afford a living to all the inhabitants, Ion and Achæus, even in their father's lifetime, led some of their followers along the Isthmus of Corinth, and down into the peninsula, where they founded two flourishing states, called, after them, A-cha´ia and I-o´ni-a. Thus, while northern Greece was pretty equally divided between the Do´ri-ans and Æ-o´li-ans, descendants and subjects of Dorus and Æolus, the peninsula was almost entirely in the hands of the I-o´ni- ans and A-chæ´ans, who built towns, cultivated the soil, and became bold navigators. They ventured farther and farther out at sea, until they were familiar with all the neighboring bays and islands.

Sailing thus from place to place, the Hellenes came at last to Crete, a large island south of Greece. This island was then governed by a very wise king called Mi´nos. The laws of this monarch were so just that all the Greeks admired them very much. When he died, they even declared that the gods had called him away to judge the dead in Ha´des, and to decide what punishments and rewards the spirits deserved.

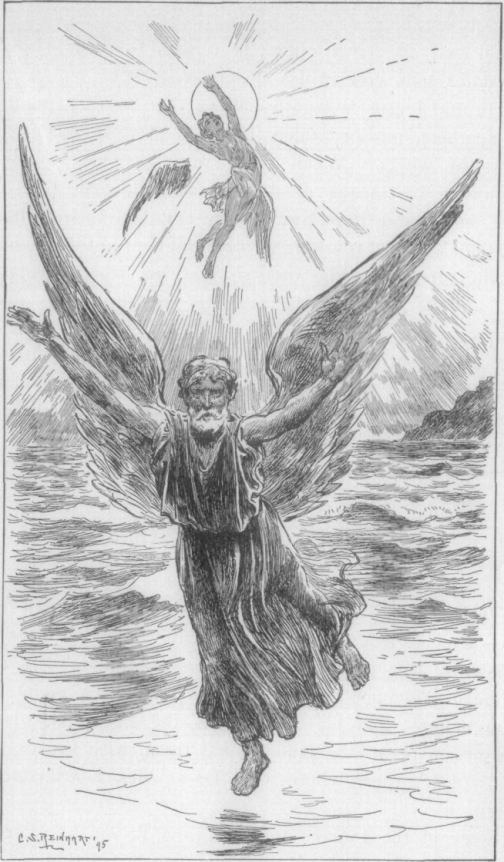

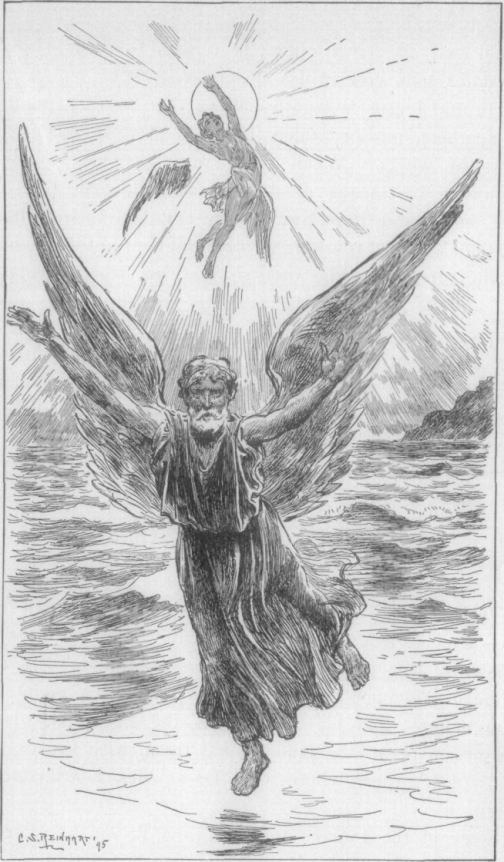

Although Minos was very wise, he had a subject named Dæd´a-lus who was even wiser than he. This man not only invented the saw and the potter's wheel, but also taught the people how to rig sails for their vessels.

As nothing but oars and paddles had hitherto been used to propel ships, this last invention seemed very wonderful; and, to compliment Dædalus, the people declared that he had given their vessels wings, and had thus enabled them to fly over the seas.

Many years after, when sails were so common that they ceased to excite any wonder, the people, forgetting that these were the wings which Dædalus had made, invented a wonderful story, which runs as follows.

Minos, King of Crete, once sent for Dædalus, and bade him build a maze, or labyrinth, with so many rooms and winding halls, that no one, once in it, could ever find his way out again.

Dædalus set to work and built a maze so intricate that neither he nor his son Ic´a-rus, who was with him, could get out. Not willing to remain there a prisoner, Dædalus soon contrived a means of escape.

Dædalus and Icarus.

He and Icarus first gathered together a large quantity of feathers, out of which Dædalus cleverly made two pairs of wings. When these were fastened to their shoulders by means of wax, father and son rose up like birds and flew away. In spite of his father's cautions, Icarus rose higher and higher, until the heat of the sun melted the wax, so that his wings dropped off, and he fell into the sea and was drowned. His father, more prudent than he, flew low, and reached Greece in safety. There he went on inventing useful things, often gazing out sadly over the waters in which Icarus had perished, and which, in honor of the drowned youth, were long known as the I-ca´ri-an Sea.

VI. THE ADVENTURES OF JASON.

The Hellenes had not long been masters of all Greece, when a Phryg´i-an called Pe´lops became master of the peninsula, which from him received the name of Pel-o-pon-ne´sus. He first taught the people to coin money; and his descendants, the Pe-lop´i-dæ, took possession of all the land around them, with the exception of Argolis, where the Da-na´i-des continued to reign.

Some of the Ionians and Achæans, driven away from their homes by the Pelopidæ, went on board their many vessels, and sailed away. They formed Hel-len´ic colonies in the neighboring islands along the coast of Asia Minor, and even in the southern part of Italy.

As some parts of Greece were very thinly settled, and as the people clustered around the towns where their rulers dwelt, there were wide, desolate tracts of land between them. Here were many wild beasts and robbers, who lay in wait for travelers on their way from one settlement to another. The robbers, who hid in the forests or mountains, were generally feared and disliked, until at last some brave young warriors made up their minds to fight against them and to kill them all. These young men were so brave that they well deserved the name of heroes, which has always been given them; and they met with many adventures about which the people loved to hear. Long after they had gone, the inhabitants, remembering their relief when the robbers were killed, taught their children to honor these brave young men almost as much as the gods, and they called the time when they lived the Heroic Age.

Not satisfied with freeing their own country from wild men and beasts, the heroes wandered far away from home in search of further adventures. These have also been told over and over again to children of all countries and ages, until every one is expected to know something about them. Fifty of these heroes, for instance, went on board of a small vessel called the "Argo," sailed across the well- known waters, and ventured boldly into unknown seas. They were in search of a Golden Fleece, which they were told they would find in Col´chis, where it was said to be guarded by a great dragon.

The leader of these fifty adventurers was Ja´son, an Æolian prince, who brought them safely to Colchis, whence, as the old stories relate, they brought back the Golden Fleece. They also brought home the king's daughter, who married Jason, and ruled his kingdom with him. Of course, as there was no such thing as a Golden Fleece, the Greeks merely used this expression to tell about the wealth which they got in the East, and carried home with them; for the voyage of the "Argo" was in reality the first distant commercial journey undertaken by the Greeks.

VII. THESEUS VISITS THE LABYRINTH.

On coming back from the quest for the Golden Fleece, the heroes returned to their own homes, where they continued their efforts to make their people happy.

The´seus, one of the heroes, returned to Athens, and founded a yearly festival in honor of the goddess Athene. This festival was called Pan-ath-e-næ´a, which means "all the worshipers of Athene." It proved a great success, and was a bond of union among the people, who thus learned each other's customs and manners, and grew more friendly than if they had always staid at home. Theseus is one of the best-known among all the Greek heroes. Besides going with Jason in the "Argo," he rid his country of many robbers, and sailed to Crete. There he visited Minos, the king, who, having some time before conquered the Athenians, forced them to send him every year a shipload of youths and maidens, to feed to a monster which he kept in the Labyrinth.

To free his country from this tribute, Theseus, of his own free will, went on board the ship. When he reached Crete, he went first into the Labyrinth, and killed the monster with his sword. Then he found his way out of the maze by means of a long thread which the king's daughter had given him. One end of it he carried with him as he entered, while the other end was fastened to the door.

His old father, ƴgeus, who had allowed him to go only after much persuasion, had told him to change the black sails of his vessel for white if he were lucky enough to escape. Theseus promised to do so, but he entirely forgot it in the joy of his return.

Ægeus, watching for the vessel day after day, saw it coming back at last; and when the sunlight fell upon the black sails, he felt sure that his son was dead.

His grief was so great at this loss, that he fell from the rock where he was standing down into the sea, and was drowned. In memory of him, the body of water near the rock is still known as the Æ-ge´an Sea.

When Theseus reached Athens, and heard of his father's grief and sudden death, his heart was filled with sorrow and remorse, and he loudly bewailed the carelessness which had cost his father's life.

Theseus now became King of Athens, and ruled his people very wisely for many years. He took part in many adventures and battles, lost two wives and a beloved son, and in his grief and old age became so cross and harsh that his people ceased to love him.

They finally grew so tired of his cruelty, that they all rose up against him, drove him out of the city, and forced him to take up his abode on the Island of Scy´ros. Then, fearing that he might return unexpectedly, they told the king of the island to watch him night and day, and to seize the first good opportunity to get rid of him. In obedience to these orders, the king escorted Theseus wherever he went; and one day, when they were both walking along the edge of a tall cliff, he suddenly pushed Theseus over it. Unable to defend or save himself, Theseus fell on some sharp rocks far below, and was instantly killed.

The Athenians rejoiced greatly when they heard of his death; but they soon forgot his harshness, remembered only his bravery and all the good he had done them in his youth, and regretted their ingratitude. Long after, as you will see, his body was carried to Athens, and buried not far from the A-crop´o-lis, which was a fortified hill or citadel in the midst of the city. Here the Athenians built a temple over his remains, and worshiped him as a god.

While Theseus was thus first fighting for his subjects, and then quarreling with them, one of his companions, the hero Her´cu-les (or Her ´a-cles) went back to the Peloponnesus, where he had been born. There his descendants, the Her-a-cli´dæ, soon began fighting with the Pelopidæ for the possession of the land.

After much warfare, the Heraclidæ were driven away, and banished to Thessaly, where they were allowed to remain only upon condition that they would not attempt to renew their quarrel with the Pelopidæ for a hundred years.

VIII. THE TERRIBLE PROPHECY.

While Theseus was reigning over the Athenians, the neighboring throne of Thebes, in Bœotia, was occupied by King La´ius and Queen Jo-cas´ta. In those days the people thought they could learn about the future by consulting the oracles, or priests who dwelt in the temples, and pretended to give mortals messages from the gods.

Hoping to learn what would become of himself and of his family, Laius sent rich gifts to the temple at Delphi, asking what would befall him in the coming years. The messenger soon returned, but, instead of bringing cheerful news, he tremblingly repeated the oracle's words: "King Laius, you will have a son who will murder his father, marry his mother, and bring destruction upon his native city!"

This news filled the king's heart with horror; and when, a few months later, a son was born to him, he made up his mind to kill him rather than let him live to commit such fearful crimes. But Laius was too gentle to harm a babe, and so ordered a servant to carry the child out of the town and put him to death.

The man obeyed the first part of the king's orders; but when he had come to a lonely spot on the mountain, he could not make up his mind to kill the poor little babe. Thinking that the child would soon die if left on this lonely spot, the servant tied him to a tree, and, going back to the city, reported that he had gotten rid of him.

No further questions were asked, and all thought that the child was dead. It was not so, however. His cries had attracted the attention of a passing shepherd, who carried him home, and, being too poor to keep him, took him to the King of Corinth. As the king had no children, he gladly adopted the little boy.

When the queen saw that the child's ankles were swollen by the cord by which he had been hung to the tree, she tenderly cared for him, and called him Œd´i-pus, which means "the swollen-footed." This nickname clung to the boy, who grew up thinking that the King and Queen of Corinth were his real parents.

IX. THE SPHINX'S RIDDLE.

When Œdipus was grown up, he once went to a festival, where his proud manners so provoked one of his companions, that he taunted him with being only a foundling. Œdipus, seeing the frightened faces around him, now for the first time began to think that perhaps he had not been told the truth about his parentage. So he consulted an oracle.

Instead of giving him a plain answer,—a thing which the oracles were seldom known to do,—the voice said, "Œdipus, beware! You are doomed to kill your father, marry your mother, and bring destruction upon your native city!"

Horrified at this prophecy, and feeling sure that the King and Queen of Corinth were his parents, and that the oracle's predictions threatened misfortunes to them, Œdipus made up his mind to leave home forever. He did not even dare to return to bid his family good- by, and he started out alone and on foot to seek his fortunes elsewhere.

As he walked, he thought of his misfortunes, and grew very bitter against the cruel goddess of fate, whom he had been taught to fear. He fancied that this goddess could rule things as she pleased, and that it was she who had said he would commit the dreadful crimes which he was trying to avoid.

After several days' aimless wandering, Œdipus came at last to some crossroads. There he met an old man riding in a chariot, and preceded by a herald, who haughtily bade Œdipus make way for his master.

As Œdipus had been brought up as a prince, he was in the habit of seeing everybody make way for him. He therefore proudly refused to stir; and when the herald raised his staff to strike, Œdipus drew his sword and killed him.

The old man, indignant at this deed of violence, stepped out of his chariot and attacked Œdipus. Now, the young man did not know that it was his father Laius whom he thus met for the first time, so he fell upon and killed him also. The servants too were all slain when they in turn attacked him; and then Œdipus calmly continued his