CHAPTER VII

“THE SUN” IN THE MEXICAN WAR

Moses Y. Beach as an Emissary of President Polk.—The Associated Press Founded in the Office of “The Sun.”—Ben Day’s Brother-in-Law Retires with a Small Fortune.

THE Beaches, father and sons, owned the Sun throughout the Mexican War, a period notable for the advance of newspaper enterprise; and Moses Yale Beach proved more than once that he was the peer of Bennett in the matter of getting news.

Shortly before war was declared—April 24, 1846—the telegraph-line was built from Philadelphia to Fort Lee, New Jersey, opposite New York. June found a line opened from New York to Boston; September, a line from New York to Albany. The ports and the capitals of the nation were no longer dependent on horse expresses, or even upon the railroads, for brief news of importance. Morse had subdued space.

For a little time after the Mexican War began there was a gap in the telegraph between Washington and New York, the line between Baltimore and Philadelphia not having been completed; but with the aid of special trains the Sun was able to present the news a few hours after it left Washington. It was, of course, not exactly fresh news, for the actual hostilities in Mexico were not heard of at Washington until May 11, more than two weeks after their accomplishment.

The good news from the battle-fields of Palo Alto and Resaca de la Palma was eighteen days in reaching New York. All Mexican news came by steamer to New Orleans or Mobile, and was forwarded from those ports, by the railroad or other means, to the nearest telegraph-station. Moses Y. Beach was instrumental in whipping up the service from the South, for he established a special railroad news service between Mobile and Montgomery, a district of Alabama where there had been much delay.

On September 11, 1846, the Sun uttered halleluiahs over the spread of the telegraph. The line to Buffalo had been opened on the previous day. The invention had been in every-day use only two years, but more than twelve hundred miles of line had been built, as follows:

|

New York to Boston

|

265

|

|

New York to Albany and Buffalo

|

507

|

|

New York to Philadelphia, Baltimore, and Washington

|

240

|

|

Philadelphia to Harrisburg

|

105

|

|

Boston to Lowell

|

26

|

|

Boston toward Portland

|

55

|

|

Ithaca to Auburn

|

40

|

|

Troy to Saratoga

|

31

|

|

Total

|

1,269

|

England had then only one hundred and seventy-five miles of telegraph. “This,” gloated the Sun, “is American enterprise!”

The Sun did not have a special correspondent in Mexico, and most of its big stories during the war, including the account of the storming of Monterey, were those sent to the New Orleans Picayune by George W. Kendall, who is supposed to have put in the mouth of General Taylor the words—

“A little more grape, Captain Bragg!”

Moses Yale Beach himself started for Mexico as a special agent of President Polk, with power to talk peace, but the negotiations between Beach and the Mexican government were broken off by a false report of General Taylor’s defeat by Santa Anna, and Mr. Beach returned to his paper.

The more facilities for news-getting the papers enjoyed, the more they printed—and the more it cost them. Each had been doing its bit on its own hook. The Sun and the Courier and Enquirer had spent extravagant sums on their horse expresses from Washington. The Sun and the Herald may have profited by hiring express-trains to race from Boston to New York with the latest news brought by the steamships, but the outflow of money was immense. The news-boats—clipper-ships, steam-vessels, and rowboats—which went down to Sandy Hook to meet incoming steamers cost the Sun, the Herald, the Courier and Enquirer, and the Journal of Commerce a pretty penny.

With the coming of the Mexican War there were special trains to be run in the South. And now the telegraph, with its expensive tolls, was magnetizing money out of every newspaper’s till. Not only that, but there was only one wire, and the correspondent who got to it first usually hogged it, paying tolls to have a chapter from the Bible, or whatever was the reporter’s favourite book, put on the wire until his story should be ready to start.

It was all wrong, and at last, through pain in the pocket, the newspapers came to realize it. At a conference held in the office of the Sun, toward the close of the Mexican War, steps were taken to lessen the waste of money, men, and time.

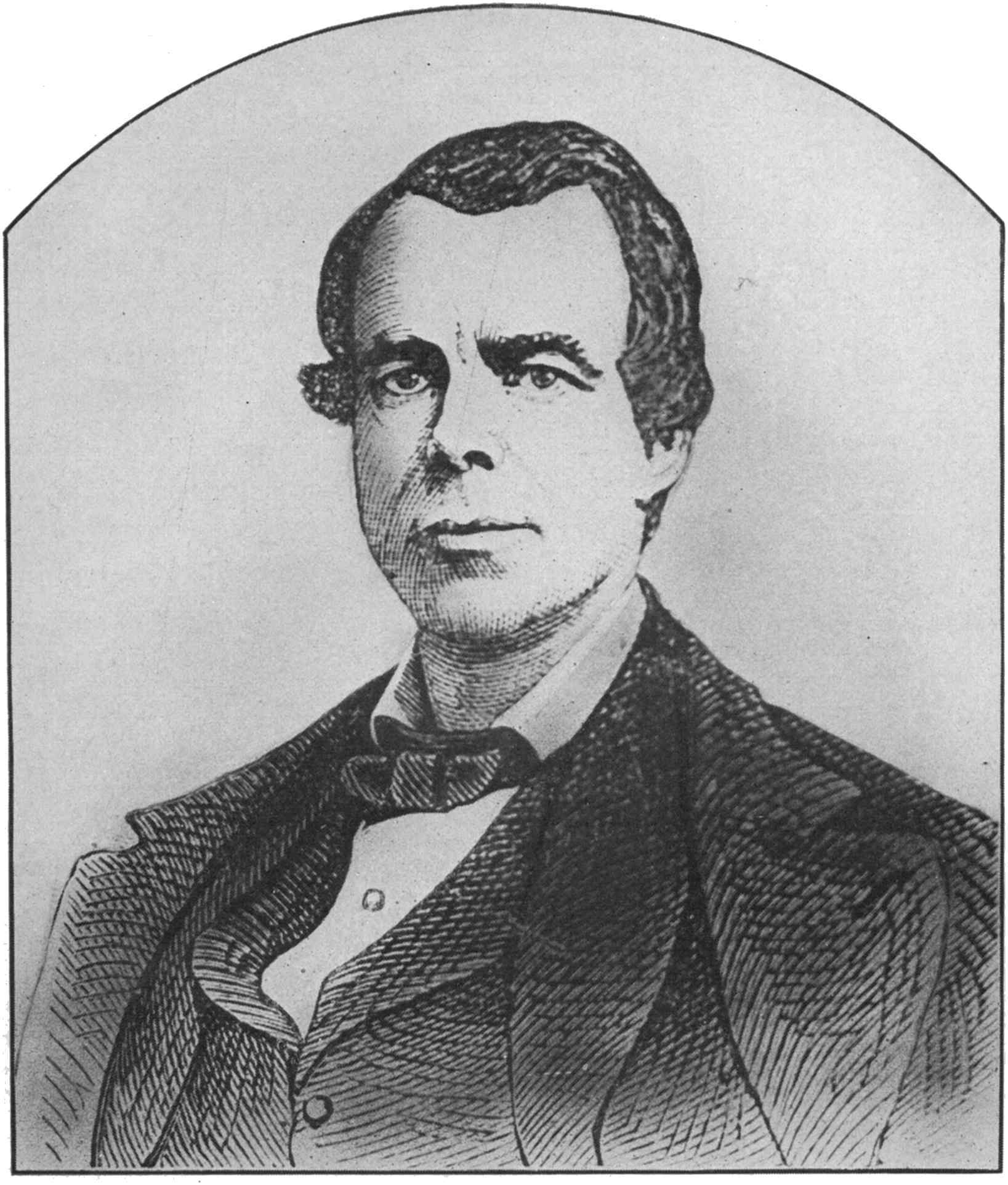

MOSES SPERRY BEACH

A Nephew of Benjamin H. Day and a Son of Moses Yale Beach. He Held “The Sun” Until Dana’s Time. This Picture is Reproduced from the First Edition of Mark Twain’s “Innocents Abroad.” Mr. Beach Was One of Clemens’s Fellow Voyagers.

At this meeting, presided over by Gerard Hallock, the veteran editor of the Journal of Commerce, there were represented the Sun, the Herald, the Tribune—the three most militant morning papers—the Courier and Enquirer, the Express, and Mr. Hallock’s own paper. The conference formed the Harbour Association, by which one fleet of news-boats would do the work for which half a dozen had been used, and the New York Associated Press, designed for cooperation in the gathering of news in centres like Washington, Albany, Boston, Philadelphia, and New Orleans. Alexander Jones, of the Journal of Commerce, became the first agent of the new organization. He had been a reporter on both sides of the Atlantic, and it was he who invented the first cipher code for use in the telegraph, saving time and tolls.

Thus in the office where some of the bitterest invective against newspaper rivals had been penned, there began an era of good feeling. So busy had the world become, and so full of news, through the new means of communication afforded by Professor Morse, that the invention of opprobrious names for Mr. Bennett ceased to be a great journalistic industry.

As an example of the change in the personal relations of the newspaper editors and proprietors, the guests present at a dinner given by Moses Y. Beach in December, 1848, when he retired from business and turned the Sun over to his sons Moses and Alfred, were the venerable Major Noah, then retired from newspaper life; Gerard Hallock, Horace Greeley, Henry J. Raymond, of the Courier and Enquirer, and James Brooks, of the Express. All praised Beach and his fourteen years of labour on the Sun, but there was never a word about Benjamin H. Day. Evidently that gentleman’s re-entry into the newspaper field as the proprietor of the True Sun had put him out of tune with his brother-in-law. Richard Adams Locke was there, however—the only relic of the first régime.

What the Sun thought of itself then is indicated in an editorial printed on December 4, when the Beach brothers relieved their father, who was in bad health:

We ask those under whose eyes the Sun does not shine from day to day—our Sun, we mean; this large and well-printed one-cent newspaper—to look it over and say whether it is not one of the wonders of the age. Does it not contain the elements of all that is valuable in a diurnal sheet? Where is more effort or enterprise expended for so small a return?

Of this effort and enterprise we feel proud; and a circulation of over fifty thousand copies of our sheet every day among at least five times that number of readers, together with the largest cash advertising patronage on this continent, convinces us that our pride is widely shared.

The Sun that Ben Day had turned over to Moses Y. Beach was no longer recognizable. Fifteen years had wrought many changes from the time when the young Yankee printer launched his venture on the tide of chance. The steamship, the railroad, and the telegraph had made over American journalism. The police-court items, the little local scandals, the animal stories—all the trifles upon which Day had made his way to prosperity—were now being shoved aside to make room for the quick, hot news that came in from many quarters. The Sun still strove for the patronage of the People, with a capital P, but it had educated them away from the elementary.

The elder Beach was enterprising, but never rash. He made the Sun a better business proposition than ever it was under Day. Ben Day carried a journalistic sword at his belt; Beach, a pen over his ear. Perhaps Day could not have brought the Sun up to a circulation of fifty thousand and a money value of a quarter of a million dollars; but, on the other hand, it is unlikely that Beach could ever have started the Sun.

Once it was started, and once he had seen how it was run, the task of keeping it going was fairly easy for him. He was a good publisher. Not content with getting out the Sun proper, he established the Weekly Sun, issued on Saturdays, and intended for country circulation, at one dollar a year. In 1848 he got out the American Sun, at twelve shillings a year, which was shipped abroad for the use of Europeans who cared to read of our rude American doings. Another venture of Beach’s was the Illustrated Sun and Monthly Literary Journal, a sixteen-page magazine full of woodcuts.

Mr. Beach had for sale at the Sun office all the latest novels in cheap editions. He wrote a little book himself—“The Wealth of New York: A Table of the Wealth of the Wealthy Citizens of New York City Who Are Estimated to Be Worth One Hundred Thousand Dollars or Over, with Brief Biographical Notices.” It sold for twenty-five cents.

Perhaps Beach was the father of the newspaper syndicate. In December, 1841, when the Sun received President Tyler’s message to Congress by special messenger, he had extra editions of one sheet printed for twenty other newspapers, using the same type for the body of the issue, and changing only the title-head. In this way such papers as the Vermont Chronicle, the Albany Advertiser, the Troy Whig, the Salem Gazette, and the Boston Times were able to give the whole text of the message to their readers without the delay and expense of setting it in type.

Here is Dana’s own estimate of the second proprietor of the Sun:

Moses Y. Beach was a business man and a newspaper manager rather than what we now understand as a journalist—that is to say, one who is both a writer and a practical conductor and director of a newspaper. Mr. Beach was a man noted for enterprise in the collection of news. In the latter days when he owned and managed the Sun in New York, the telegraph was only established between Washington and Boston, though toward the end of his career it was extended, if I am not mistaken, as far towards the South as Montgomery in Alabama. The news from Europe was then brought to Halifax by steamers, just as the news from Mexico was brought to New Orleans. Mr. Beach’s energy found a successful field in establishing expresses brought by messengers on horseback from Halifax to Boston and from New Orleans to Montgomery, thus bringing the news of Europe and the news of the Mexican War to New York much earlier than they could have arrived by the ordinary public conveyance. With him were associated, sooner or later, two or three of the other New York papers; but the energy with which he carried through the undertaking made him a conspicuous and distinguished figure in the journalism of the city. The final result was the organization of the New York Associated Press, which has now become a world-embracing establishment for the collection of news of every description, which it furnishes to its members in this city and to other newspapers in every part of the country. Under the stimulus of Mr. Beach’s energetic intellect, aided by the cheapness of its price, the Sun became in his hands an important and profitable establishment. Yet he is scarcely to be classed among the prominent journalists of his day.

Through conservatism, good business sense, and steady work, Moses Y. Beach amassed from the Sun what was then a handsome fortune, and when he retired he was only forty-eight. His last years were spent at the town of his birth, Wallingford, where he died on July 19, 1868, six months after the Sun had passed out of the hands of a Beach and into the hands of a Dana.

(From Photo in the Possession of Mrs. Jennie Beach Gasper)

ALFRED ELY BEACH

A Son of Moses Y. Beach; He Left “The Sun” to Conduct the “Scientific American.”

Beach Brothers, as the new ownership of the Sun was entitled, made but one important change in the appearance and character of the paper during the next few years.

Up to the coming of the telegraph the Sun had devoted its first page to advertising, with a spice of reading-matter that usually was in the form of reprint—miscellany, as some newspapermen call it, or bogus, as most printers term it. But when telegraphic news came to be common but costly, newspapers began to see the importance of attracting the casual reader by means of display on the front page. The Beaches presently used one or two columns of the latest telegraph-matter on the first page; sometimes the whole page would be so occupied.

In 1850, from July to December, they issued an Evening Sun, which carried no advertising.

On April 6, 1852, Alfred Ely Beach, more concerned with scientific matters than with the routine of daily publication, withdrew from the Sun, which passed into the sole possession of Moses S. Beach, then only thirty years old. It was reported that when the partnership was dissolved the division was based on a total valuation of two hundred and fifty thousand dollars for the paper which, less than nineteen years before, Ben Day had started with an old hand-press and a hatful of type. Horace Greeley, telling a committee of the British parliament about American newspapers, named that sum as the amount for which the Sun was valued in the sale by brother to brother.

“It was very cheap,” he added.