CHAPTER XVII

SOME GENIUS IN AN OLD ROOM

Lord, Managing Editor for Thirty-Turn Years.—Clarke, Magician of the Copy Desk.—Ethics, Fair Play and Democracy.—“The Evening Sun” and Those Who Make It.

FOR forty-seven years the city or news room of the Sun was on the third floor of the brick building at the south corner of Nassau and Frankfort Streets, a five-story house built for Tammany Hall in 1811, when that organization found its quarters in Martling’s Tavern—a few doors south, on part of the site of the present Tribune Building—too small for its robust membership.

In the days of Grand Sachems William Mooney, Matthew L. Davis, Lorenzo B. Shepard, Elijah F. Purdy, Isaac V. Fowler, Nelson J. Waterbury, and William D. Kennedy, and the big and little bosses, including Tweed, this third-floor room had been used as a general meeting-hall. It was here, in 1835, that the Locofoco—later the Equal Rights—party was born after a conflict in which the regular Tammany men, finding themselves in the minority, turned off the gas and left the reformers to meet by the light of locofoco matches. It was a room from which many a Democrat was hurled because he preferred De Witt Clinton to Tammany’s favourite, Martin Van Buren. Two flights of long, straight stairs led to the ground floor. They were hard to go up; they must have been extremely painful to go down bouncing.

It was a long, wide, barnlike room, lighted by five windows that looked upon Park Row and the City Hall. The stout old timbers were bare in the ceiling and in them were embedded various hooks and ring-bolts to which, once upon a time, was attached gymnasium apparatus used by a turn verein, which hired the room when the Tammanyites did not need it.

It was not a beautiful room. Mr. Dana never did anything to improve it except in a utilitarian way, and from the time when he bought the building from the Tammany Society, in 1867, until it was torn down in 1915, the old place looked very much the same. Of course, new gas-jets were added, these to be followed by electric-light wires, until the upper air had a jungle-like appearance, and there were rude, inexpensive desks and telephone-booths.

The floor was efficient, for it was covered with rubber matting that deadened alike the quick footstep of Dana and the thundering stride of pugilistic champions who came in to see the sporting editor. But the city room’s only ornaments were men and their genius. Here wrote Ralph and Chamberlin, Spears and Irwin, and all the rest of the fine reporters of the old building’s years.

Near the windows of this shabby room were the desks of the men who planned news-hunts, chose the hunters, and mounted their trophies. Six desks handled all the news-matter in the old city room of the Sun. The managing editor sat at a roll-top in the northwest corner, near a door that led to Mr. Dana’s room. A little distance to the east was the night editor’s desk. At the large flat-top desk near the managing editor three men sat—the cable editor, who handled all foreign news; the “Albany man,” who edited articles from the State and national capitals and all of New York State; and the telegraph editor, who took care of all other wire matter.

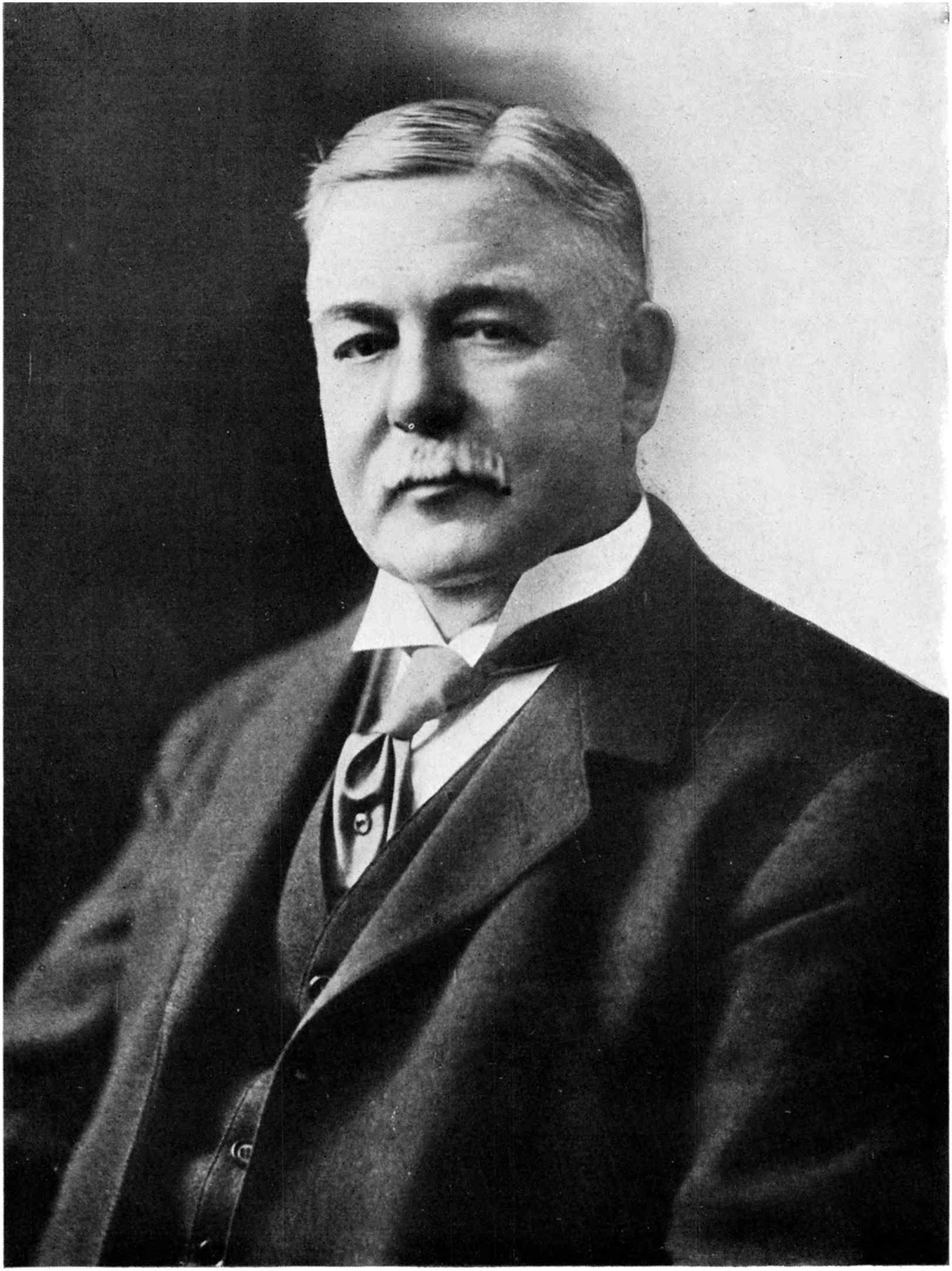

CHESTER SANDERS LORD

In the southwest corner of the room was a double desk at which the city editor sat from 10 A.M. until 5 P.M., when the night city editor came in. Next to the city editor’s desk was the roll-top of the assistant city editor, also used by the assistant night city editor. Beyond that was the desk of the suburban or “Jersey” editor. Nearest the door, so that the noise of ten-thousand-dollar challenges to twenty-round combat would not disturb the whole room, was the desk of the sporting editor.

In the fifty years that have passed since Dana bought the Sun, the changes in the heads of the news departments have been comparatively few. True, the news office has not been as fortunate as the editorial rooms, where only three men, Charles A. Dana, Paul Dana, and Edward P. Mitchell, have been actual editors-in-chief; but the list of managing editors and night city editors is not long. Before the day of Chester S. Lord, the managing editors were, in order: Isaac W. England, Amos J. Cummings, William Young, and Ballard Smith. Since Lord’s retirement the managing editors have been James Luby, William Harris, and Keats Speed.

The city editors have been John Williams, Larry Kane, W. M. Rosebault, William Young, John B. Bogart (1873–1890), Daniel F. Kellogg (1890–1902), George B. Mallon (1902–1914), and Kenneth Lord, the present city editor, a son of Chester S. Lord.

The night city editors before the long reign of Selah Merrill Clarke—of whom more will be said presently—were Henry W. Odion, Elijah M. Rewey, and Ambrose W. Lyman, all of whom had previously been Sun reporters, and all of whom remained with the Sun, in various capacities, for many years. Rewey was the exchange editor from 1887 to 1903, and was variously employed at other important desk posts until his death in 1916. Since Mr. Clarke’s retirement, in 1912, the night city editors have been Joseph W. Bishop, J. W. Phoebus, Eugene Doane, Marion G. Scheitlin, and M. A. Rose.

The night editors of the Sun, whose function it is to make up the paper and to “sit in” when the managing editors are absent, have been Dr. John B. Wood, the “great American condenser”; Garret P. Serviss, now with the Evening Journal; Charles M. Fairbanks, Carr V. Van Anda (1893–1904), now managing editor of the New York Times; George M. Smith (1904–1912), the present managing editor of the Evening Sun; and Joseph W. Bishop.

In the eighties, the nineties, and the first decade of the present century the front corners of the city room were occupied, six nights a week, by two men closely identified with the Sun’s progress in getting and preparing news. These, Chester S. Lord and S. M. Clarke, were looked up to by Sun men, and by Park Row generally, as essential parts of the Sun.

Lord, through his city editors, reporters, and correspondents, got the news. If it was metropolitan news—and until the latter days of July, 1914, New York was the news-centre of the world, so far as American papers were concerned—Clarke helped to get it and then to present it after the unapproachably artistic manner of the Sun. In the years of Lord and Clarke more than a billion copies of the Sun went out containing news stories written by men whom Lord had hired and whose work had passed beneath the hand of Clarke.

Chester Sanders Lord, who was managing editor of the Sun from 1880 to 1913, was born in Romulus, New York, in 1850, the son of the Rev. Edward Lord, a Presbyterian clergyman who was chaplain of the One Hundred and Tenth Regiment of New York Volunteer Infantry in the Civil War. Chester Lord studied at Hamilton College in 1869 and 1870, and went from college to be associate editor of the Oswego Advertiser. In 1872 he came to the Sun as a reporter, and covered part of Horace Greeley’s campaign for the Presidency in that year. After nine months as a reporter he was assigned by the managing editor, Cummings, to the suburban desk, where he remained for four years.

In the fall of 1877 he bought the Syracuse Standard, but in six weeks he returned to the Sun and became assistant night city editor under Ambrose W. Lyman, the predecessor of S. M. Clarke. Ballard Smith, who succeeded William Young as managing editor in 1878, named Lord as his assistant, and Lord succeeded Ballard Smith as managing editor on December 3, 1880.

For thirty-three years Lord inspected applicants for places in the news departments of the Sun, and decided whether they would fit into the human structure that Dana had built. Edward G. Riggs, who knew him as well as any one, has written thus of him:

Like Dana, he has been a great judge of men. His discernment has been little short of miraculous. Calm, dispassionate, without the slightest atom of impulse, as wise as a serpent and as gentle as a dove, Lord got about him a staff that has been regarded by newspapermen as the most brilliant in the country. Independent of thought, with a placid idea of the dignity of his place, ever ready to concede the other fellow’s point of view even though maintaining his own, Lord was never known in all the years of his managing editorship of the Sun to utter an unkind word to any man on the paper, no matter how humble his station.

One of Lord’s notable performances as managing editor was the perfecting of the Sun’s system of collecting election returns. Before 1880 the correspondents had sent in the election figures in a conscientious but rather inefficient manner—by towns, or cities. Lord picked out a reliable correspondent in each county of New York State and gave to the chosen man the responsibility of sending to the Sun, at nine o’clock on election night, an estimate of the result in his particular county. This was to be followed at eleven o’clock, if necessary, with the corrected figures.

“Don’t tell us how your city, or township, or village went,” he said to the correspondents. “Let us have your best estimate on the county. Don’t spare the telephone or the telegraph, either to collect the returns or to get them into the Sun office.”

The telephone was just coming into general use for the transmission of news, and Lord saw its possibilities on an election night.

As a result of the new system, improved from year to year, the Sun became what it is—the election-night authority on what has happened. So confident was the Sun of its figures on the night of the Presidential election of 1884 that it, alone of all the New York papers, declared the next morning that Mr. Cleveland had defeated Mr. Blaine, although the Sun had been one of the most strenuous opponents of the Democratic candidate. Blaine, who had wired to the Sun for its estimates, got the first news of his defeat from Lord. Eight years later, when Mr. Cleveland defeated President Harrison, the winner’s political chief of staff, Daniel S. Lamont, received the first tidings of the great and unexpected victory from Mr. Lord.

In the late eighties the Sun was supplementing its Associated Press news service with a valuable corps of special correspondents scattered all over America and Europe. The news received from these Sun men led to the establishment, by William M. Laffan, then publisher of the Sun, of a Sun news agency which was called the Laffan Bureau. This service, originated for the purpose of covering special events in the live way of the Sun, was suddenly called upon to cover the whole news field of the world in a more comprehensive way.

Lord’s part in this work, when Dana decided to break with the Associated Press, has been graphically described by Mr. Riggs:

“Chester,” said Mr. Dana one afternoon early in the nineties, leaning over Lord’s desk, “I have just torn up my Associated Press franchise. We’ve got to have the news of the world to-morrow morning, and we’ve got to get it ourselves.”

“Don’t let that fret you, Mr. Dana,” replied Lord. “You’ve got a Dante class on hand to-night. You just go home and enjoy yourself. I’ll have the news for you all right.”

Dana always said that he didn’t enjoy his Dante class a single bit that night; but he didn’t go near the Sun office, neither did he communicate with the office. He banked on Lord, and the next morning and ever afterward Lord made good on the independent service. He built up the Laffan Bureau, which more recently has become the Sun News Service, and the special correspondents of the paper in all parts of the world see to it that the Sun gets the news.

A task like that which Dana thrust on Lord might have paralyzed the average managing editor of a great metropolitan newspaper confronted by keen and powerful competitors. It was unheard of in journalism. It had never been attempted before. Lord, with calm courage and confidence, sent off thousands of telegrams and cable despatches that night. Many were shots in the air, but the majority were bull’s-eyes, as the next morning’s issue of the Sun proved.

Was Dana delighted? If you had seen him hop, skip, and jump into the office that morning, you’d have received your answer. When Lord turned up at his desk in the afternoon, Dana rushed out from his chief editor’s office, grasped him about the shoulders, and chuckled:

“Chester, you’re a brick, you’re a trump. You’re the John L. Sullivan of newspaperdom!”

The Laffan Bureau, which assimilated the old United Press, became a news syndicate the service of which was sought by dozens of American papers whose editors admired the Sun’s manner of handling news. The Laffan Bureau lasted until 1916, when the Sun, through its purchase by Frank A. Munsey, absorbed Mr. Munsey’s New York Press, which had the Associated Press service.

Among Mr. Lord’s fortunate traits as managing editor were his ability to choose good correspondents all over the world and his entire confidence in them after they were selected. No matter what other correspondents wrote, the Sun stood by its own men. They were on the spot; they should know the truth as well as any one else could.

Months before Aguinaldo’s insurrection the Sun man at Manila, P. G. McDonnell, kept insisting that the Filipino chieftain would revolt. The other New York newspapers laughed at the Sun for seeing ghosts, but McDonnell was right.

Newspaper readers will remember that in 1904 the fall of Port Arthur was announced three or four times in about as many months, and each time the Sun appeared to be beaten on the news until the next day, when it was discovered that the Russians were still holding out. All the Sun did about the matter was to notify its Tokyo correspondent, John T. Swift, that when Port Arthur really fell it would expect to hear from him by cable at “double urgent” rates. At midnight of January 1, 1905, four months after these instructions were given to Swift, the Sun got a “double urgent” message:

Port Arthur fallen—SWIFT.

No other paper in New York had the news. The Sun rubbed it in editorially on January 3:

Deeply conscious as we are of the deplorable lack of modern enterprise which has hitherto deprived the Sun of the distinction of repeatedly announcing the fall of Port Arthur, we have to content ourselves with the reflection that when finally the Sun did print the fall of Port Arthur, it was so.

Soon after the election of Woodrow Wilson, in 1912, the head of the Sun bureau in Washington, the late Elting A. Fowler, made the prediction that William Jennings Bryan would be named as Secretary of State. Nearly every other metropolitan newspaper either ignored the story, or ridiculed it as absurd and impossible. The Sun never made inquiry of Fowler as to the source of his information. He had been a Sun man for ten years, and that was enough. Fowler repeated and reiterated that Bryan would be the head of the new Cabinet, and sure enough, he was.

The Sun correspondent in a city five hundred miles from New York was covering a great murder mystery. Every other New York newspaper of importance had sent from two to five men to handle the story; the Sun sent none. The correspondent saw that the New York men were getting sheaves of telegrams from their newspapers, directing them in detail how to tell the story, and to what length; so he sent a message to the Sun advising it of the large numbers of New York reporters engaged on the mystery, and of the amount of matter they were preparing to send. Had the Sun any instructions for him? Yes, it had. The reply came swiftly:

Use your own judgment—CHESTER S. LORD.

That was the Sun way, and the Sun printed the correspondent’s stories, whether they were one column long, or six. The Sun could not see how an editor in New York could know more about a distant murder than a correspondent on the spot.

It was the Sun’s way, once a man was taken on, to keep him as long as it could. One day Mr. Lord sent for Samuel Hopkins Adams, then a reporter, and asked him whether he would like to go away fishing.

“A Sunday story?” inquired Adams.

“No, not exactly,” said Mr. Lord. “A vacation, rather. You’ve been fired. Go away, but come back, say, next Tuesday, and go to work, and it’ll be all right. Don’t worry!”

Adams learned that a suit for libel had been brought against the paper by an individual who had been made an unpleasant figure in a police story which Adams had written.

A few days after Adams returned to his duties Mr. Dana came out of his room and asked the city editor, Mr. Kellogg, the name of the reporter who had written an article to which he pointed. Kellogg told Dana that Adams was the author, and Dana strode across the room and bestowed upon the reporter one of his brief and much prized commentaries of approval. Then he looked at Adams more closely, and, with raised eyebrows, walked to the managing editor’s desk.

“Who is that young man?” he asked Mr. Lord, indicating Adams with a movement of the head.

Mr. Lord murmured something.

“Didn’t I order him discharged a few days ago?” said Mr. Dana.

Another but more prolonged murmur from Mr. Lord. Adams got up from his desk to efface himself, but as he left the room he caught the voice of Mr. Dana, a trifle higher and a bit plaintive:

“Why is it, Mr. Lord, that I never succeed in discharging any of your bright young men?”

Adams did not wait for the answer.

This story, while typical of Lord, is not typical of Dana. For every word of censure he had a hundred words of praise. He read the paper—every line of it—for virtues to be commended rather than for faults to be condemned.

“Who wrote the two sticks about the lame girl? A good touch; that’s the Sun idea!”

If a new man had written something he liked—even a ten-line paragraph—the editor of the Sun would cross the room to shake the man’s hand and say:

“Good work!”

The spirit he radiated was contagious. The men, encouraged by Dana, spread faith to one another. The “Sun” spirit—the envious of other newspapers were wont to refer to those who had it as “the Sun’s Mutual Admiration Society”—did and does much to make the Sun. The men lived the socialism of art. If a new reporter received a difficult assignment, ten older men were ready to tell him, in a kindly and not at all didactic way, how to find the short cut.

Perhaps some part of the democracy of the Sun office has come from the fact that men have rarely been taken in at the top. It was Dana’s plan to catch young men with unformed ideas of journalism and make Sun men of them. They went on the paper as cubs at fifteen dollars a week—or even as office-boys—and worked their way to be “space men,” if they had it in their noddles.

All space men were free and equal in the Jeffersonian sense. Their pay was eight dollars a column. That one man made one hundred and fifty dollars in a week when his neighbour made only fifty was usually the result, not of the system, but of the difference between the men. Some were harder workers than others, or better fitted by experience for more important stories; and some were born money-makers. If a diligent reporter, through no fault of his own, was making small “bills,” the city editor would see to it that something profitable fell to him—perhaps a long and easily written Sunday article.

Through changed conditions in newspaper make-up and policies, the space system in the payment of reporters is now practically extinct. It had good points and bad ones. Undoubtedly it developed a large number of men to whom a salary would not have been attractive. Some, to whose style and activities the space system lent itself, remained in the profession longer than they would otherwise have stayed. On the other hand, it was not always fair to reporters with whom a condensed style was natural. The dynamics of a two-inch article, the very value of which lies in its brevity, cannot be measured with a space-rule.

The Sun’s ideas of fairness do not end with itself and its men. It has always had a proper consideration for the feelings of the innocent bystander. It never harms the weak, or stoops to get news in a dishonourable or unbecoming way. It would be hard to devise a set of rules of newspaper ethics, but a few examples of things that the Sun doesn’t do may illuminate.

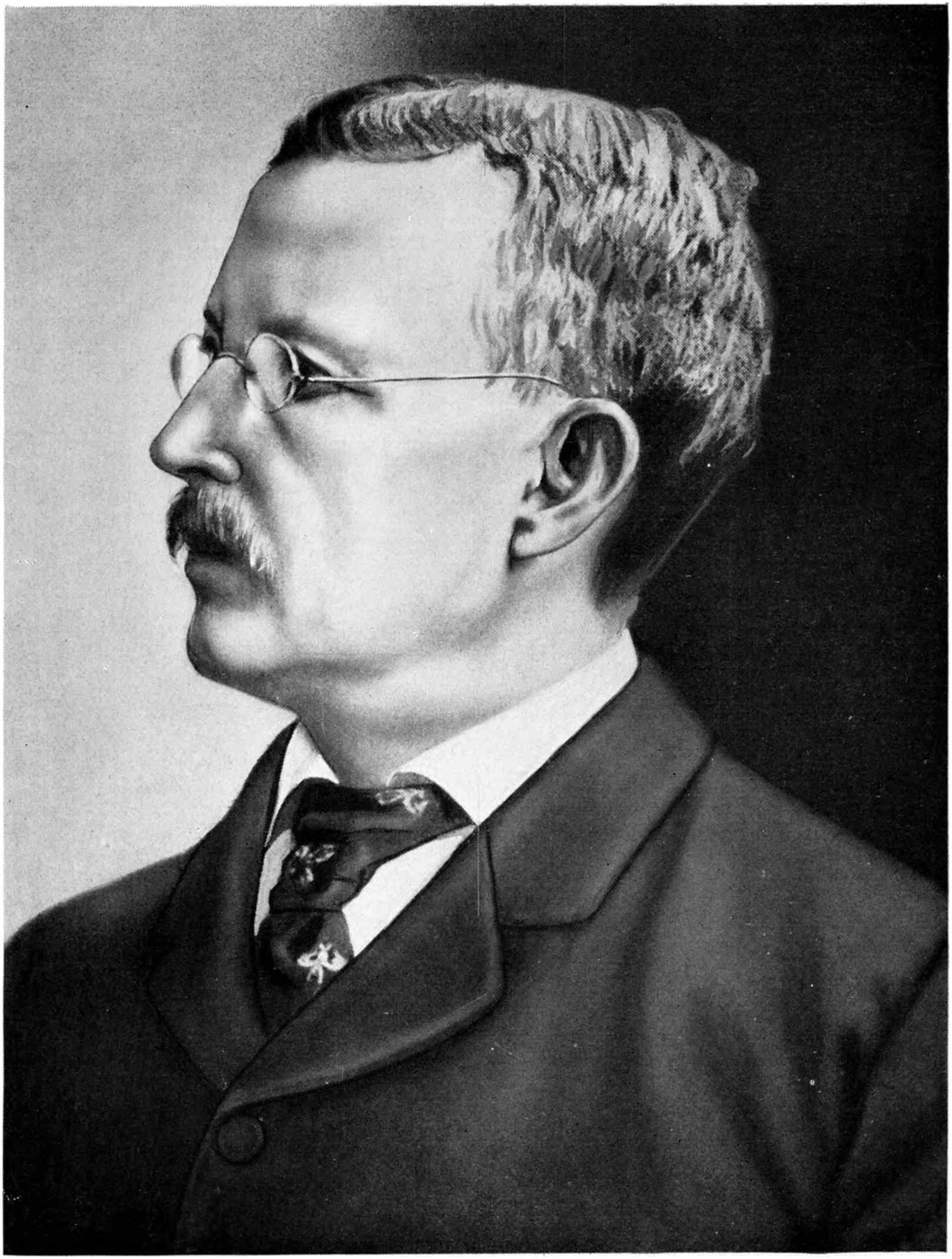

SELAH MERRILL CLARKE

Soon after one of the Sun’s most brilliant reporters had come on the paper, he was sent to report the wedding of a noted sporting man and a famous stage beauty, the marriage ceremony being performed by a picturesque Tammany alderman. The reporter returned to the office with a lot of amusing detail, which he recited in brief to the night city editor.

“Just the facts of the marriage, please,” said Mr. Clarke. “The two most important events in the life of a woman are her marriage and her death. Neither should be treated flippantly.”

Another reporter wrote an amusing story about a fat policeman posted at the Battery, who chased a tramp through a pool of rain-water. The policeman fell into the water, and the tramp got away. No report of the occurrence was made at police headquarters, but a Sun man saw the incident and wrote it.

“It’s an amusing story,” said Clarke to the reporter, “but they read the papers at police headquarters, and this policeman may be put on trial for not reporting the escape of the hobo. Suppose we drop this classic on the floor?”

A telegraph messenger-boy once wrote a letter to the police commissioner, telling him how to break up the cadets (panders) of the East Side. A Sun man found the lad and got an interesting interview with him.

“Leave my name out, won’t you?” the messenger said to the reporter. “If you print it, I may lose my job.”

He was told that his name was known in the Sun office, but that the reporter would present his appeal.

“Did you find the messenger?” Clarke asked the reporter on his arrival.

The Sun man replied that he had found him, and that the interview was interesting and exclusive. Before he had an opportunity to repeat the boy’s plea for anonymity, Clarke said:

“Is it going to hurt the boy if we print his name? If it is, leave it out, and refer to him by a fictitious number.”

Two reporters, one from the Sun and one from another big daily, went one night to interview a famous man on an important subject. The Sun man returned and wrote a brief story containing none of the big news which it had been hoped he might get. The other newspaper came out with some startling revelations, gleaned from the same interview. Mr. Lord showed the rival paper’s article to the Sun reporter, with a mild inquiry as to the reason for the Sun’s failure to get the news.

“We both gave our word,” said the reporter, “that we would keep back that piece of news for three days, even from our offices.”

“Son,” said Mr. Lord, “you are a great man!”

That was the Lord phrase of acquittal.

One of the big occurrences in the investigation of the life-insurance companies in 1905 was a report which was read to the investigating committee in executive session. Every newspaper yearned for the contents of the document. After the committee adjourned, a member of it whispered to a Sun reporter:

“There is a bundle of those reports just inside the door of the committee room. I should think that five dollars given to a scrub-woman would probably get a copy for you.”

The Sun man, knowing the value of the report, and not content to act on his own estimate of Sun ethics, telephoned the temptation to the city editor, Mr. Mallon.

“A Sun man who would do that would lose his job,” was the instant decision.

A couple of days after Stephen Tyng Mather, recently First Assistant Secretary of the Interior, went on the Sun as a reporter, the city editor, Mr. Bogart, called him to his desk.

“Mr. Mather,” said Bogart, “an admirer of the Sun has sent me a turkey. Of course, I cannot accept it. Please take it to his house in Harlem and explain why; but don’t hurt his feelings.”

Mather had just come from college, where he had never learned that the ethics of journalism might require a reporter to become a deliverer of poultry, but he took the turkey. It does not detract from the moral of the story to say that Mather and another young reporter, neither quite understanding the Sun’s stern code, took the bird to the Fellowcraft Club and had it roasted—a fact of which Mr. Bogart may have been unaware until now.

The best news-handler that journalism has seen, Selah Merrill Clarke, was night city editor of the Sun for thirty-one years. He came to the paper in 1881 from the New York World, where he had been employed as a reporter, and later as a desk man. In the early seventies he wrote for the World a story of a suicide, and one of the newspapers of that day said of it that neither Dickens nor Wilkie Collins, with all the time they could ask, could have surpassed it. His story of the milkman’s ride down the valley of the Mill River, warning the inhabitants that the dam had broken at the Ashfield reservoir, near Northampton, Massachusetts (May 16, 1874), was another classic that attracted the attention of editors, including Dana.

Clarke never thought well of himself as a reporter, and often said that in that capacity he was a failure. As a judge of news values, or news presentation, or as a giver of the fine literary touch which lent to the Sun’s articles that indescribable tone not found in other papers, Clarke stood almost alone.

The city editor of a New York newspaper sows seeds; the night city editor re-seeds barren spots, waters wilting items, and cuts and bags the harvest. The city editor sends men out all day for news; the night city editor judges what they bring in, and decides what space it shall have. In the handling of a big story, on which five or fifteen reporters may be engaged, the night city editor has to put together as many different writings in such a way that the reader may go smoothly from beginning to end. Chance may decree that the poorest writer has brought in the biggest news, and the man on the desk must supply quality as well as judgment.

At such work Clarke was a master. It has been said of him that by the eliding stroke of his pencil and the insertion of perhaps a single word he could change the commonplace to literature. No reporter ever worked on the Sun but wished, at one time or another, to thank Clarke for saving him from himself. Clarke had the faculty of seeing instantly the opportunity for improvement that the reporter might have seen an hour or a day later.

Clarke got about New York very little, but he knew the city from Arthur Kill to Pelham Bay; knew it just as a general at headquarters knows the terrain on which his troops are fighting, but which he himself has never seen. He had the map of New York in his brain. When an alarm of fire came in from an obscure corner, he knew what lumber-yards or oil-refineries were near the blaze, and whether that was a point where the water pressure was likely to fail.

Clarke’s memory was uncanny; it seemed to have photographed every issue of the Sun for years. It was a saying that while Clarke stayed the Sun needed neither an index nor a “morgue”—that biographical cabinet in which newspapers keep records of men and affairs.

Twenty-five years after the Beecher-Tilton trial a three-line death-notice came to Clarke’s desk. He read the dead man’s name and summoned a reporter.

“This man was a juror in the Beecher case,” said Clarke. “Look in the file of February 6 or 7, 1875, and I think you’ll find that this man stood up and made an interruption. Write a little piece about it.”

A Sun man who reported the funeral of Russell Sage at Lawrence, Long Island, in July, 1906, returned to the office and told Mr. Clarke that an acquaintance of the Sage family had told him, on the train coming back, the contents of the old man’s will—a document for which the reading public eagerly waited. The reporter laid his informant’s card before the night city editor. Clarke studied the name on it for a