CHAPTER XXIX

CHECK-MATE

For some time already there had been a certain amount of commotion in the Palace. Mirrab's shouts when first she saw the combat, then her high-voiced altercation with Don Miguel, had roused the attention of some of the guard who were stationed in the cloister green court close by. Some of the gentlemen too were astir.

Wessex himself soon after he had reached his own apartments heard the sound of angry voices proceeding from the room which he had just quitted. He could hear nothing distinctly, but it seemed to him as if a woman and a man were quarrelling violently. He tried to shut his ears to the sound. He would hear nothing, know nothing more of the wanton who had fooled and mocked him.

But there are certain instincts in every chivalrous man, which will not be gainsaid; among these is the impulse to go at once to the assistance of a woman if she be in trouble or difficulty.

It was that impulse and nothing more which caused Wessex to retrace his footsteps. He had some difficulty in finding his way, now that there was no moonlight to guide him, but as soon as he re-entered the last room, which was next to the audience chamber, he heard the ominous "A moi!" of his dying opponent. Also all round him the obvious commotion of a number of footsteps all tending towards the same direction.

An icy horror suddenly gripped his heart. Not daring to imagine what had occurred, he hurried on. By instinct, for he could see nothing, he contrived to find and open the door, and still going forward he presently stumbled against something which lay heavy and inert at his feet.

In a moment he was on his knees, touching the prostrate body with a gentle hand; realizing that the unfortunate young man had fallen on his face, he tried with infinite care to lift and turn him as tenderly as he could.

Then suddenly he became conscious of another presence in the room. Nothing more than a ghostlike form of white, almost as rigid as the murdered man himself, whilst from the corridors close by the sound of approaching footsteps, still hesitating which way to go, became more and more distinct. A murmur of distant voices too gradually took on a definite sound.

"This way."

"No, that."

"In the court . . ."

"No! the audience chamber!"

The ghostly white-clad figure appeared as if turned to stone.

"Through the window," whispered Wessex with sudden vehemence, "it is not high!—quick! fly, in the name of God! while there's yet time!"

That was his only instinct now. He could not think of her as the woman he had loved, he understood nothing, knew nothing; but in the intense gloom which surrounded him he had lost sight of the witchlike and horrible vision which had dealt a death-blow to his love, he seemed only to see the green bosquets of the park, the pond, the marguerites, and another white-clad figure, a girlish face crowned with the golden halo of purity and innocence.

The wild passion which he had felt for her changed to an agonizing horror, not only of her deed, but at the thought of seeing her surrounded, rough-handled by the guard, shamed and treated as a mad and drunken wanton.

He despised himself for his own weakness, but at this awful and supreme moment, when he realized that the idol which he had set up and worshipped was nothing but defiled mud, he felt for her only tenderness and pity.

Love had touched him once, and he knew now that nothing would ever tear her image completely from out his heart. Love, great, ardent, immutable, was dead; but death is oft more powerful than life, and his dead love pleaded for his chivalry, for his protection, with all the power of sweet memories, and aided by the agonizing grip of cold, stiff hands clinging to his heartstrings.

He pointed once more to the open window.

"Quick! in God's name!"

The girl moved towards him.

"Ah no, no, for pity's sake. Go!"

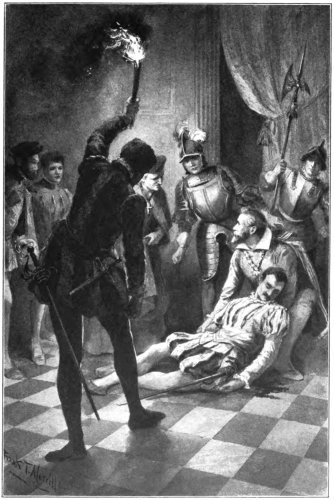

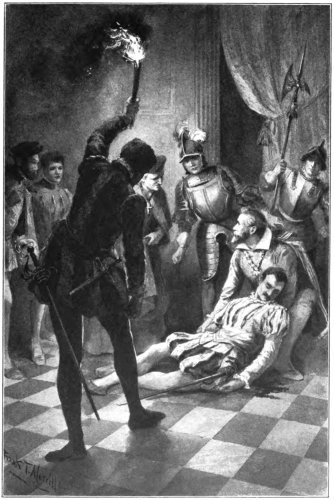

There was not a second to be lost. Mirrab, realizing her danger, was sobered and alert. The next moment she was clinging to the window-sill and measuring its height from the terrace below. It was but a few feet. As agile as a cat she flung herself over, and disappeared into the gloom just as the door leading into the audience chamber was thrown violently open, and a group of people—gentlemen, guard, servitors—bearing torches came rushing into the room.

"Water! . . . a leech!—quick, some of you!" commanded Wessex, who held Don Miguel's head propped against his knee.

"What is it? . . ." queried every one with unanimous breath.

Some pressed forward, snatching the flaming torches from the hands of the servitors. In a moment Wessex and the dead Marquis were surrounded, and the room flooded with weird, flickering light.

From the door of the apartments on the left a suave and urbane voice had sounded softly—

"What is it?"

"The Spanish Marquis," murmured the foremost man in the crowd.

"Wounded?" queried another.

"Nay! I fear me dead," said Wessex quietly.

Then the groups parted instinctively, for the same urbane voice had repeated its query in tones of the gravest anxiety.

"I was at prayers, and heard this noise. . . . What is it?"

The Cardinal de Moreno now stood beside the dead body of his friend.

"Your Grace! and? . . ."

"Alas, Your Eminence!" replied Wessex, "Don Miguel de Suarez is dead."

"Alas, Your Eminence! Don Miguel de Suarez is dead."

The Cardinal made no comment, and the next moment was seen to stoop and pick up something from the ground.

"But how?" queried one of the gentlemen.

"A duel?" added another.

"No, not a duel, seemingly," said His Eminence softly. "Don Miguel's sword and dagger are both sheathed."

He turned to the captain of the guard, who was standing close beside him.

"Will this dagger explain the mystery, think you, my son?" he asked, handing a small weapon to the soldier. "I picked it up just now."

The guard—he was but a young man—took the dagger from His Eminence's hand, and looked at it attentively. Those who were nearest to him noticed that he suddenly started, and that the hand which held the narrow pointed blade trembled visibly.

"Your Grace's dagger!" he said at last, handing the weapon to Wessex. "It has Your Grace's arms upon the hilt."

Dead silence followed these simple words. The Duke seemed half dazed, and mechanically took the dagger from the captain's hand; the blade still bore on it the marks of Don Miguel's blood.

"Yes! it is my dagger," he murmured mechanically.

"But no doubt Your Grace can explain . . ." suggested His Eminence indulgently.

Wessex was about to reply when one of the guard suddenly interposed.

"I seemed to see a woman flying through the gardens just now, captain," he said, addressing his officer.

"A woman?" asked His Eminence. "What woman?"

"Nay, my lord, I couldn't see distinctly," replied the soldier, "but she was dressed all in white, and ran very quickly along the terrace not far from this window."

"Then Your Grace will perhaps be able to tell us . . ." suggested the Cardinal with utmost benevolence.

"I can tell Your Eminence nothing," replied Wessex coldly. "I was in this room all the time and saw no woman near."

"Your Grace was here?" said His Eminence in gentle tones of profound astonishment, "alone with Don Miguel de Suarez? . . . The woman . . ."

"There was no woman here," rejoined the Duke of Wessex firmly, "and I was alone with Don Miguel de Suarez."

There was dead silence now, the moon, pale, inquisitive, brilliant, peeped in through the window to see what was amiss. She saw a number of men recoiling, awestruck, from a small group composed of a dead man and of the first gentleman in the land self-confessed as a murderer. No one dared to speak, the moment was too solemn, too terrible, for any speech save a half-smothered sigh of horror.

The captain of the guard was the first to recollect his duty.

"Your Grace's sword . . ." he began, somewhat shamefacedly.

"Ah yes! I had forgot," said Wessex quietly, as he rose to his feet. He drew his sword from its sheath, and with one quick, sudden wrench, broke the blade across his knee. Then he threw the pieces of steel on the ground.

"I am ready to follow you, friend captain," he said, with all the hauteur, all the light, easy graciousness so peculiar to himself.

The groups parted silently, almost respectfully, as His Grace of Wessex passed out of the room—a prisoner.