CHAPTER XXXIII

IN THE LORD CHANCELLOR'S COURT

The great Hall at Westminster was already thronged with people at an early hour of the morning, and the servants of the Knight Marshal and the Lord Warden of the Fleet had much ado to keep the crowd back with their tipstaves.

All London was taking a holiday to-day: an enforced holiday as far as the workers and merchants were concerned, for there surely would be no business doing in the City when such great goings-on were occurring at Westminster.

The trial of His Grace the Duke of Wessex on a charge of murder! A trial which, seeing that the accused had confessed to the crime, could but end in a sentence of death.

It is not every day that it is given to humbler folk to see so proud a gentleman arraigned as any common vagabond might be, and to note how a great nobleman may look when threatened with the hangman's rope.

Is there aught in the world half so cruel as a crowd?

And His Grace had been very popular: always looked upon, even by the meanest in the land, as the most perfect embodiment of English pride and English grandeur, he had always had withal that certain graciousness of manner which the populace will love, and which disarms envy.

But with the exception of his own friends, people of his own rank and station, who knew him and his character intimately, the people at large never for a moment questioned his guilt.

He had confessed! surely that was enough! The loutish brains of the lower proletariat did not care to go beyond that obvious self-evident fact. The meaner the nature of a man, the more ready is he to acknowledge evil, he seeks it out, recognizes it under every garb. Who, among the majority of people, cared to seek for sublime self-sacrifice in an ordinary confession of crime?

The wiseacres and learned men, the more wealthy burgesses, and people of more consideration, were content with a few philosophical reflections anent the instability of human nature and the evil influences of Court life and of great wealth.

No one cared about the man! it was the pageant they all liked. What thought had the mob of the agonizing rack to which a proud soul would necessarily be subjected during the course of a wearisome and elaborate trial? They only wanted to see a show, the robes of the judges, the assembly of peers, and that one central figure, the first gentleman in England, once almost a king—now a felon!

A fine sight, my masters! His Grace of Wessex in a criminal dock!

Places in the Hall were at a premium. The 'prentices were well to the fore as usual; like so many eel-like creatures, they had slipped into the front rank as soon as the great doors had been opened. Some few waifs and vagrants—acute and greedy of gain—were making good trade with small wooden benches, which they sold at threepence the piece to those who desired a better view.

The women were all wearing becoming gowns, sombre of hue as befitted the occasion. His Grace of Wessex was noted for his avowed admiration for the beautiful sex. They had all brought large white kerchiefs, for they anticipated some exquisite emotions. His Grace was so handsome! there was sure to be an occasion for tears.

But only as a pleasurable sentiment! Like one feels at the play, where the actor expresses feelings, yet is himself cold and unimpassioned. What His Grace himself would feel was never considered. The crowd had come to see, some had paid threepence for a clearer sight of the accused, and all meant to enjoy themselves this day.

Proud Wessex! thou hast sunk to this, a spectacle for a common holiday! Thy face will be scanned lest one twitch escape! thy shoulders if they stoop, thy neck if it bend! A thousand eyes will be fixed upon thee in curiosity, in derision—perchance in pity!

Ye gods, what a fall!

The Lord High Steward of England was expected to arrive at ten o'clock. In the centre of the great court a large scaffold had been erected, not far from the Lord Chancellor's Court. In the middle of this there was placed a chair higher than the rest and covered with a cloth, which bore the royal arms embroidered at the four corners.

This was for my Lord High Steward.

Each side of him were the seats for the peers who were to be the triers. Great names were whispered, as the servants of the Knight Marshal arranged these in their respective places. There was the chair for the Earl of Kent, and my lord of Sussex, the Earl of Hertford, and Lord Saint John of Basing, and a score of others, for there were twenty-four triers in all.

On a lower form were the seats for the judges, and in a hollow place cut in the scaffold itself, and immediately at the feet of my Lord High Steward, the Clerk of the Crown would sit with his secondary.

And facing the judges and the peers was the bar, where presently the exalted prisoner would stand.

No one was here yet of the greater personages, the servants were still busy putting everything to right, but some gentlemen of the Queen's household had already arrived, and several noble lords who would be mere spectators. His Grace's friends could easily be distinguished by the sombreness of their garb and the air of grief upon their faces. Mr. Thomas Norton, the Queen's printer, was sorting his papers and cutting his pens, and two gentlemen ushers were receiving final instructions from Garter King-at-Arms.

There was indeed plenty for the idlers to see. Great ropes had been drawn across the further portions of the Hall, leaving a wide passage from the main entrance right down the centre and up to the Lord High Steward's seat. Behind these ropes the crowd was forcibly kept back. And the gossip and the noise went on apace. Laughter too and merry jests, for this was a holiday, my masters, presently to be brought to a close—after the death sentence had been passed and every one dispersed—with lively jousts and copious sacks of ale.

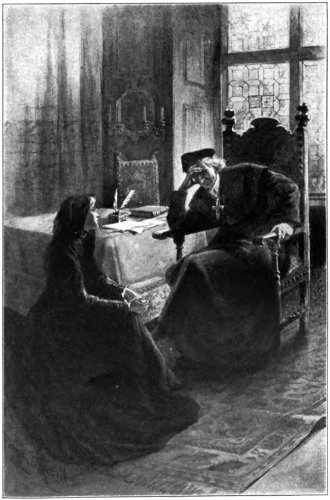

But of all this excitement and bustle not a sound penetrated within the precincts of the Lord Chancellor's Court, where His Eminence the Cardinal de Moreno sat patiently waiting.

Desirous above all things of escaping observation, he had driven over from Hampton Court in the early dawn, and wrapped in a flowing black cloak, which effectually hid his purple robes, he had slipped into the Hall and thence into the Inner Court, even before the crowd had begun to collect. Since then he had sat here quietly buried in thoughts, calmly looking forward to the interview, which was destined finally to unravel the tangled skein of his own diplomacy. Once more the destinies of Europe were hanging on a thread: a girl's love for a man.

Well! so be it! His Eminence loved these palpitating situations, these hairbreadth escapes from perilous positions which were the wine and salt of his existence. He was ready to stake his whole future career upon a woman's love! He, who had scoffed all his life at sentimental passions, who had used every emotion of the human heart, aye! and its every suffering, merely as so many assets in the account of his far-reaching policy, he now saw his whole future depending on the strength of a girl's feelings.

That she would certainly come, he never for a moment held in doubt. In these days the commands of a sovereign were akin to the dictates of God; to disobey was a matter of treason. Aye! she would come, sure enough! not only because of her allegiance to the Queen, but because of her intense, vital interest in the great trial of the day.

So His Eminence waited patiently in the Lord Chancellor's Court, which gave straight into the great Hall itself, until the appointed time.

Exactly at half-past nine the door of the room was opened, and Ursula Glynde walked in. The Cardinal rose from his seat and would have approached her, but she retreated a step or two as he came near and said coldly—

"'Tis Your Eminence who desired my presence?"

"And 'tis well that you came, my daughter," he replied kindly.

"I was commanded by Her Majesty to attend; I had not come of my own free will."

She spoke quietly but very stiffly, as one who is merely performing a social duty, without either pleasure or dislike. The Cardinal studied her face keenly, but obviously she had been told nothing by the Queen as to the precise object of this interview.

She looked pale and wan: there was a look of acute suffering round the childlike mouth, which would have seemed pathetic to any one save to this callous dissector of human hearts. Her eyes appeared unnaturally large, with great dilated pupils and dry eyelids. She was dressed in deep black, with a thick veil over her golden hair, which gave her a nunlike appearance, and altogether made her look older, and strangely different from the gay and girlish figure so full of life and animation which had been one of the brightest ornaments of old Hampton Court Palace. The Cardinal motioned her to a seat, which she took, then she waited with perfect composure until His Eminence chose to speak.

"My child," he said at last, bringing his voice down to tones of the greatest gentleness, "I would wish you to remember that it is an old man who speaks to you: one who has seen much of the world, learnt much, understood much. Will you try and trust him?"

"What does Your Eminence desire of me?" she rejoined coldly.

"Nay! 'tis not a question of desire, my daughter, I would merely wish to give you some advice."

"I am listening to Your Eminence."

"I am listening to Your Eminence."

The Cardinal had taken the precaution of placing himself with his back to the light which entered, grey and mournful, through the tall leaded window above. He was sitting near a table covered with writing materials, and in a large high-backed tapestried chair, which further enhanced the ponderous dignity of his appearance, whilst helping to envelop his face in complete shadow. Ursula sat opposite to him on a low stool, that same grey light falling full upon her pale face, which was turned serenely, quite impassively upon her interlocutor.

His Eminence rested his elbow on the arm of his chair and his head in his delicate white hands. The purple robes fell round him in majestic folds, the gold crucifix at his breast sparkled with jewels: he was a past master in the art of mise-en-scène, and knew the full value of impressive pauses and of effective attitudes during a momentous conversation, more especially when he had to deal with a woman. His present silence helped to set the young girl's aching nerves on edge, and he noticed with a sense of inward satisfaction that her composure was not as profound as she would have him think: there was a distinct tremor in the delicate nostrils, a jerkiness in the movements of her hand, as she smoothed out the folds of her sombre gown.

"My dear child," he began once more, and this time in tones of more pronounced severity, "a brave man, a good and chivalrous gentleman, is about to suffer not only death, but horrible disgrace. . . . On the other side of these thin walls the preparations are ready for his trial by a group of men, whose duty it will be anon to allow the justice of this realm to take its relentless course. The accused will stand self-convicted, yet innocent, before them."

Once more the Cardinal paused: only for a second this time. He noticed that the young girl had visibly shuddered, but she made no attempt to speak.

"Innocent, I repeat it," he resumed after a while. "His Grace has many friends; not one of them will believe that he could be capable of so foul a crime. But he has confessed to it. He will be condemned, and he—the proudest man in England—will die a felon's death. . . ."

"I knew all that, Your Eminence," she said quietly. "Why should you repeat it now?"

"Only because . . ." said the Cardinal with seeming hesitation, "you must forgive an old man, my child . . . methought you loved His Grace of Wessex and . . ."

"Why does Your Eminence pause?" she rejoined. "You thought that I loved His Grace of Wessex . . . and . . . ?"

"And yet, my child, through a strange, nay, a culpable obstinacy, you, who could save him not only from death, but also from dishonour, you remain silent!"

"Your Eminence errs, as every one else has erred," she replied with the same cold placidity; "I am silent because I have naught to say."

The Cardinal smiled with kind indulgence, like a father who understands and forgives the sins of his child.

"Let us explain, my daughter," he said. "That fatal night, when the Marquis de Suarez was killed, a woman was seen to fly from that part of the Palace where the tragedy had just taken place. . . ."

"Well?"

"Do you not see that if that woman came forward fearlessly and owned the truth, that it was from jealousy or even to defend her honour that His Grace killed Don Miguel, do you not see that no judge then will find him guilty of a wilful and premeditated crime?"

"Then why does not that woman come forward?" she retorted with the first sign of vehemence, noticeable in the quiver of her voice and the sudden flash in her pale cheeks, "why does she not speak? she for whose sake His Grace of Wessex not only took a man's life but is willing to sacrifice his honour?"

"She seems to have disappeared," said His Eminence softly, "perhaps she is dead. . . . Some say it was you," he added, leaning slightly forward and dropping his voice to a whisper.

"They lie," she replied. "I was not there. 'Tis not for me His Grace of Wessex will suffer both death and disgrace in silence."

This time His Eminence did not smile. There had been a sudden flash in his eyes at this quick, sharp retort—a sudden flash as suddenly veiled again. Then his heavy lids drooped; once more he looked paternal, benevolent, only just with a soupçon of sternness in his impassive face, the aloofness of an austere man towards the weaknesses of more mundane creatures.

Never for a moment did he reveal to the unwary young girl all that he had guessed through her last unguarded speech.

Her love for Wessex! that he knew already! Its depth alone was a revelation to him. But her jealousy! How her lips had trembled and her hand twitched when speaking of another, an unknown woman who had called forth in Wessex that spirit of noble self-sacrifice, that immolation of his own honour and dignity, which had finally landed him in a criminal dock.

A woman's passion and a woman's jealousy! Two precious assets in His Eminence's present balance. He pondered over what he had learned, and victory loomed more certain than before. He loved this present situation, the acute tension of this palpitating moment, when he seemed to hold this beautiful woman's soul, bare and fettered, writhing with agony and self-torture.

To dissect a human heart! to watch its every quiver, to note the effect of every searing iron applied with a skilful hand! then to achieve success in the end through subtle arts and devices seemingly so full of benevolence, yet instinct with the most refined, most far-reaching cruelty! This was the form of enjoyment which more than any other appealed to the jaded mind of this blasé diplomatist. The feline nature within him loved this game with the trembling mouse.

But outwardly he sighed, a deep sigh of disappointment.

"Ah! if they lie!" he said, a gentle tone of melancholy pervading his entire attitude, "if indeed it was not you, my daughter, who were with Don Miguel that night . . . then naught can save His Grace. . . . He has suffered in silence. . . . He will die to-morrow in silence . . . and innocent."

He had risen from his chair, and began wandering about the narrow room—aimlessly—as if lost in thought. Ursula was staring straight before her. The first revelation of her present danger had suddenly come to her. As in a flash she had suddenly realized that this man had sent for her in order to use her for his own ends. She felt that she was literally in the position of the mouse about to be sacrificed to the greedy ambition of this feline creature, who had neither rectitude nor compunction where his ambition was at stake.

Yet after that one betrayal of her emotions she had made a vigorous effort to regain her self-control. Every instinct of self-preservation was on the alert now, and yet she knew already that she was bound to succumb. To what she could not guess, but she felt herself the weaker vessel of the two. He was calm and cruel, passionless and tortuous, whilst she felt with all her heart and soul and with all her senses.

And though he could not now see her face the Cardinal studied her every movement. He could see her figure stiffen with the iron determination to retain her self-possession, and inwardly he smiled, for he knew that the next moment all that rigidity would vanish, the marble statue would become living clay, the palsied nerves would quiver with horror, and she herself would fall, a weeping, wailing creature, supplicating at his feet.

And this by such a simple method!

Just the opening of a door! gently, noiselessly, until the sound from the Great Hall entered into this inner room, and voices clearly detached themselves from the confusing hubbub.

Then His Eminence whispered, "Hush, my daughter! listen! my Lord High Steward is speaking."

At first perhaps she did not hear, certainly she did not understand, for her attitude did not relax its uncompromising stiffness.

Lord Chandois was delivering his first speech.

"My lords and gentlemen," he said, "ye are here assembled this day that ye may try Robert d'Esclade, Duke of Wessex, for a grievous and heinous crime, which he hath wilfully committed."

It was just the opening and shutting of a door—the claw of the cat upon the neck of the mouse. At first sound of Wessex' name Ursula had risen to her feet, straight and rigid like a machine. She did not look towards the door, but fixed her eyes on him—her tormentor—fascinated as a bird, to whom a snake has beckoned and bade it to come nigh.

The colour rose to her cheeks, the reality was gradually dawning upon her. That man who spoke in the Great Hall beyond was a judge—there were other judges there too. When she arrived at Westminster she had seen a great concourse of people, heard the names of great legal dignitaries whispered round her, and of peers who had been summoned for a great occasion.

That occasion was the trial of the Duke of Wessex on a charge of murder.

"No, no, no," she whispered hoarsely, somewhat wildly, as she took a step forward; "no, no, no . . . not yet . . . it is not true . . . not yet——"

The thin crust of ice which had enveloped her heart was melting in the broad garish light of the actual, awful fact—the commencement of Wessex' trial.

She tottered and might have fallen but for the table close beside her, against which she leant.

Her calm and composure were flying from her bit by bit. She had at last begun to understand—to realize. Up to now it had all been so shadowy, so remote, almost like a dream. She had not seen Wessex since that last happy moment when he had pressed her against his heart . . . since then she had only heard rumours . . . wild statements . . . she knew of his self-accusation—the terrible crime which had been committed—but her heart had been numbed through the very appalling nature of the catastrophe following so closely upon her budding happiness . . . it had all been intangible all this while . . . whilst now . . .

"The Duke hath made confession," said the Cardinal, and his voice seemed to come as if in direct answer to her thoughts. "In an hour at most judgment will be pronounced against him, and then sentence of death."

She passed her hand across her moist forehead, trying to collect her scattered senses. She looked once or twice at him in helpless, appealing misery, but his face now was stern and implacable, he seemed to her to be the presentment of a relentless justice about to fall on an innocent man. Her throat felt parched, her lips were dry, yet she tried to speak.

"It cannot be . . ." she repeated mechanically, "it cannot be . . . no, no, my lord, you are powerful . . . you are great and clever . . . you will find a means to save him . . . you will . . . you will . . . you sent for me. . . . Oh! was it in order to torture me like this that you sent for me?"

"My child. . . ."

"That woman?" she continued wildly, not heeding him, "that woman . . . where is she? . . . find her, my lord . . . find her, and let me speak to her. . . . Oh! I'll find the right words to melt her heart . . . she must speak . . . she must tell the truth . . . she cannot let him die . . . no, no . . . not like that. . . ."

Gone was all her pride, all her icy reserve, even jealousy had vanished before the awful inevitableness of his dishonour and his death. She would have dragged herself at the feet of those judges who were about to condemn him, of this man who was taking a cruel delight in torturing her; nay! she would have knelt and kissed the hands of that unknown rival, for whose sake she had endured the terrible mental tortures of the past few days, if only she could wrench from her the truth which would set him free from all this disgrace.

"That woman!" she repeated with agonizing passion, "that woman . . . where is she? . . ."

"She stands now before me," said the Cardinal sternly, "repentant, I hope, ready to speak the truth."

"No! no! it is false!" she protested vehemently, "false I tell you! It was not I . . ."

Her voice broke in a pitiable, wistful sob, which would have melted a heart less stony than that which beat in the Cardinal's ambitious breast.

"Oh! have I not endured enough?" she murmured half to herself, half in appealing misery to him. "Jealousy—hate for that woman whom he loves as he never hath loved me . . . whom he loves better than his honour . . . for whose sake he will stand there anon, branded with infamy. . . ."

Her knees gave way under her, she fell half prostrate on the floor at the very feet of her tormentor.

"Find her, my lord," she sobbed passionately, "find her . . . you can . . . you can. . . ."

But for sole answer he once more pushed the door ajar.

Another voice came from the body of the hall now, that of Mr. Barham, the Queen's Serjeant—

"And having proved Robert d'Esclade, Duke of Wessex, guilty of this most heinous murder, I, on behalf of the Crown, will presently ask you, my lord, to pass sentence of death upon him."

"No, no, no—not death!" she moaned, "not death. . . . They are mad, my lord—are they not mad? . . . He guilty of murder! Oh! will no one come forward to prove him innocent?"

"No one can do that but you, my daughter," replied His Eminence sternly, as he once more closed the door.

"But you do not understand. In God's name, what would you have me do? I loved him, it is true, but . . . it was another woman . . . not I! another woman, whose honour is dearer to him than his own . . . for whose sake he killed . . . for whose sake he is silent . . . for whose sake he will die . . . but that woman was not I . . . not I!"

"Alas!" he replied placidly, "then indeed nothing can save His Grace from the block. . . ."

He sighed and returned to his former place beside the table, like a man who has done all that duty demanded of him, and now is weary and ready to let destiny take its course.

Ursula watched him dully, stupidly; she could not read just then what went on behind that mask of suave benevolence. Could she have read the Cardinal's innermost thoughts she would have seen that complete satisfaction filled his ambitious heart. He knew that he had succeeded, it was but a question of time . . . a few minutes, perhaps; but he had a good quarter of an hour to spare, in which the tortured soul before him would fight its last fight with despair. There was the long arraignment to be read out by the Clerk of the Crown, then the names of the triers to be called out in their order—all that, before the prisoner was actually called to the bar. Oh yes! he had plenty of time, now that he was sure of victory.

The girl wandered mechanically towards the door, her trembling hand sought the latch, but was too weak to turn it. She glued her ear to the lock and perchance heard a word or two, for even the Cardinal caught the sound of a loud voice reading the deadly indictment.

"The prisoner hath confessed . . .

"This most heinous crime . . .

"For which sentence of death . . .

"Return his precept and bring forth the prisoner."

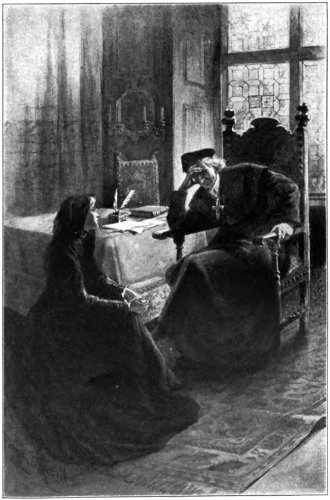

Ursula straightened out her girlish figure; with a firm hand now she smoothed her veil over her hair, and rearranged the disordered folds of her kerchief. She crossed the room with an unfaltering step, and once more took a seat on the low stool opposite to His Eminence the Cardinal.

She seemed to have reassumed the same icy calm which she had worn earlier in the interview; she was quite pale again, and all traces of tears had disappeared from her eyes.

Quite instinctively, certainly against his will, the Cardinal failed to return the steady gaze which she now fixed upon him. As she sat there close to him, her great lustrous eyes trying to search his very soul, he knew that at last she had guessed.

She knew that he was fully aware of the fact that she was not the woman for whose sake the Duke of Wessex was suffering condemnation at this very moment. All the meshes of the base intrigue which had landed the man she loved in a felon's dock escaped her utterly, but this much she realized, that the Cardinal had worked for the Duke's undoing, that he knew who her rival was, that he was wilfully shielding that woman, whilst callously sacrificing her—Ursula Glynde—to the success of some further scheme.

She knew all that, yet she did not hesitate. Her love for Wessex had filled all her life—first as a child, then as an ignorant girl worshipping an ideal. When she saw him, and in him saw the embodiment of all her most romantic beliefs, she loved him with all the passionate ardour of her newly awakened woman's heart. From the moment that his touch had thrilled her, that his voice had set her temples throbbing, that her pure lips had met his own, she had given him her whole love, given herself to him body and soul for his happiness and her own.

So great was her love that jealousy had not killed it; it had changed her joy into sorrow, her happiness into bitterness, but the heart which she gave to him she was powerless to take away. He had fooled her, led her to believe in his love for her, but his life was as precious to her now as it had been that afternoon—which seemed so long ago—when she first raised her eyes to his and met his ardent gaze.

She was face to face with the most cruel problem ever set before a human heart, for she firmly believed that if through her self-sacrifice she saved him from death and dishonour, he would nevertheless inevitably turn to the other woman, for whose sake he was suffering now; yet she was ready with the sacrifice, because of the selflessness of her love.

How well the Cardinal had managed the tragedy which had parted two noble hearts! Each believed the other treacherous and guilty, yet each was prepared to lay down life, honour, happiness for the sake of the loved one.

"Your Eminence," said Ursula very quietly after a little while, "you said just now that I could save His Grace of Wessex from unmerited disgrace and death. Tell me now, what must I do?"

"It is simple enough, my daughter," he replied, still avoiding her clear, steadfast gaze; "you have but to speak the truth."

"The truth, they say, oft lies hidden in a well, my lord," she rejoined. "I pray Your Eminence to guide me to its depths."

"I can but guide your memory, my daughter, to the events of the fateful night when Don Miguel was murdered."

"Yes?"

"You were there, in the Audience Chamber, were you not?"

"I was there," she repeated mechanically.

"With Don Miguel de Suarez, who, taking advantage of the late hour and the loneliness of this part of the Palace . . . insulted you . . . or . . ."

"Let us say that he insulted me. . . ."

"His Grace then came upon the scene?"

"Just as Your Eminence describes it."

"And 'twas to defend your honour that the Duke of Wessex killed Don Miguel."

"To defend mine honour the Duke of Wessex killed Don Miguel."

"This you will swear to be true?"

"Without hope of absolution."

"And you will make this tardy confession, my daughter, to His Grace's judges freely?"

"Whenever it is deemed necessary I will make the confession to His Grace's judges freely."

She swayed as if her senses were leaving her. Instinctively the Cardinal put out his arm to support her, but with a mighty effort she drew herself together, and looked down upon him with all the regal majesty of her own sublime self-sacrifice.

But, flushed with victory, His Eminence cared nothing for the contempt of the vanquished. It had been a hard-fought battle. His Grace was saved from death and Queen Mary Tudor could not help but keep her word. It was a triumph indeed!

He touched a hand-bell, a servant appeared. A few whispered instructions and the end was accomplished at last.

But, God in Heaven, at what terrible cost!