IX.

January 28, 1907.

IN the romantic history of African exploration and development there is no more interesting chapter than that relating to the Congo. In 1854 Livingstone finished a great journey into the continent; in it he had visited a portion of the district drained by the Kasai River. In his final journey we find him again within the district of what to-day forms the Congo Free State; he discovered Lake Moero in 1867 and Lake Bangwelo in 1868; he visited the southern portion of Tanganika in 1869, and followed the course of the Congo to Nyangwe.

At that time no one knew, few if any suspected, that the river he was following had connection with the Congo. Livingstone himself believed that it formed the uppermost part of the Nile, and in all the district where he saw it, its course from south to north would naturally lead to that opinion. It was his heart’s desire to trace the further course and determine whether it were really the Nile or a part of some other great river. Death prevented his answering the question.

Backed by the New York Herald and the Daily Telegraph, Stanley, on November 17, 1874, struck inland from the eastern coast of Africa, with the purpose of determining the question as to the final course of the great river flowing northward, discovered by his missionary predecessor. He circumnavigated Lake Victoria, discovered Lake Albert Edward, and made the first complete examination of the shore of Tanganika. He reached the Lualaba—Livingstone’s north-flowing stream,—and, embarking on its waters, devoted himself to following it to its ending.

There is no need of recalling the interesting experiences and adventures of his journey; every one has read his narrative. Suffice it to say that his great river presently turned westward so far north of the Congo mouth that one would never dream of connecting the two waters, but as unexpectedly it turned again toward the southwest and finally showed itself to be the Congo. During the interval between Stanley’s two great expeditions—the one in which he found Livingstone and the one in which he demonstrated the identity of the Lualaba and the Congo—there had been a growing interest in Europe in everything pertaining to the Dark Continent.

This interest, which was widely spread, was focused into definite action by Leopold II., king of the Belgians, who invited the most notable explorers of Africa, the presidents of the great geographical societies, politicians, and philanthropists, who were interested in the progress and development of Africa, to a geographic conference to be held in Brussels. The gathering took place in September, 1876, at the king’s palace. Germany, Austria, Belgium, France, Great Britain, Italy, and Russia were represented. The thirty-seven members who made up the conference represented the best of European thought.

From this conference there developed the International African Association. This Association organized a series of local national associations, through which the different countries interested should conduct investigations and explorations in Africa upon a uniform plan, and with reference to the same ideas and purposes. It possessed, also, a governing international commission, of which the king of the Belgians was the president, and upon which were representatives of Germany, and France, and the United States, Minister Sanford replacing a British representative. This committee laid out a definite plan of exploration. Its first expedition was to go in from the east coast at Zanzibar, passing to Tanganika. The commission adopted as the flag of the International African Association a ground of blue upon which shone a single star of gold.

The Association’s plan included the discovery of the best routes into the interior of Africa; the establishment of posts where investigators and explorers could not only make headquarters but from which they might draw supplies needed for their journey. These advantages were to be extended to any traveler. The expeditions themselves were national in character, being left to the initiative of the local national committees which had been developed by the Association. This Association existed from 1876 to 1884. During that time six Belgian, one German, and two French expeditions were organized, accomplishing results of importance.

It was in November, 1877, that the result of Stanley’s expedition came to the knowledge of the world. It wrought a revolution in the views regarding Central Africa. In Belgium it produced at once a radical change of plan. The idea of entering the heart of Africa from Zanzibar was abandoned. The future operations of the A. I. A.—at least, so far as Belgium was concerned—would extend themselves from the Congo mouth up through the vast river system which Stanley had made known. Details of this mode of procedure were so promptly developed that when Stanley reached Marseilles in January, 1878, he found an urgent invitation from the king of the Belgians to come to Brussels for the discussion of plans of conference.

After a full study of the matter, it was determined by the Belgian committee that a society should be organized with the title of the Committee of Studies of the High Congo. This, it will be understood, was purely a Belgian enterprise. It had for its purpose the occupation and exploitation of the whole Congo district. For this purpose prompt action was necessary. In February, 1879, Stanley went to Zanzibar and collected a body of workmen and carriers. With this force of helpers and a number of white subordinates he entered the Congo with a little fleet of five steamers, bearing the flag of the A. I. A. Arrived at Vivi, where he established a central station, he arranged for the transportation of his steamers in sections by human carriers to the Stanley Pool above the rapids.

He worked with feverish haste. France was pressing her work of exploration, and there was danger of her seizing much of the coveted territory. Portugal, too, was showing a renewed interest and activity, and might prove a dangerous rival in the new plans. Native chiefs were visited and influenced to form treaties giving up their rights of rulership in their own territories to the Association. Lands were secured for the erection of stations; the whole river was traversed from Stanley Pool to Stanley Falls, for the purpose of making these treaties and securing the best points for locating the stations. The Committee of Studies of the High Congo now possessed at least treaty rights over a vast area of country, and by them governmental powers over vast multitudes of people. It had these rights, it had a flag, but it was not yet a government, and it stood in constant danger of difficulties with governments. About this time it changed its name from the Committee of Studies of the High Congo to the International Association of the Congo.

Meantime events were taking place which threatened the existence of the Association. Portugal began to assert claims and rights which had long been in abeyance. She proposed to organize the territory at the Congo mouth, and which, of course, was of the greatest importance to the Association, into a governmental district and assume its administration. In this project she found willing assistance on the part of England.

Never particularly enthusiastic over the scheme of Leopold II., England had shown no interest at all during the later part of all these movements. It is true that she was represented at the first conference held at Brussels; it will be remembered that in the later organization an American had replaced the English representative. No work had been done of any consequence by a British committee. No expedition had been sent out. By the treaty with Portugal, England would at one stroke render the whole Congo practically worthless. The crisis had come. France and Germany came to King Leopold’s help. The former recognized the political activity and status of the Association and promised to respect its doings; Germany protested vigorously against the Anglo-Portuguese treaty, which fell through.

Bismarck, who favored the plans of the Belgian monarch in Africa, officially recognized, on November 3, 1884, the Association as a sovereign power, and invited representatives of the powers to Berlin for the purpose of establishing an international agreement upon the following points: First, commercial freedom in the basin of the Congo and its tributaries; second, application to the Congo and the Niger of the principle of freedom of navigation; third, the definition of the formalities to be observed in order that new occupations of African shores should be considered as effective. The conference began November 15th, Bismarck himself presiding. Fifteen powers participated—Germany, Austria, Belgium, Denmark, Spain, United States, France, Great Britain, Italy, The Netherlands, Portugal, Russia, Sweden, Norway, and Turkey.

As the result of three months of deliberation, the Congo State was added to the list of independent nations, with King Leopold II. as its ruler. Promptly the new power was recognized by the different nations of the world.

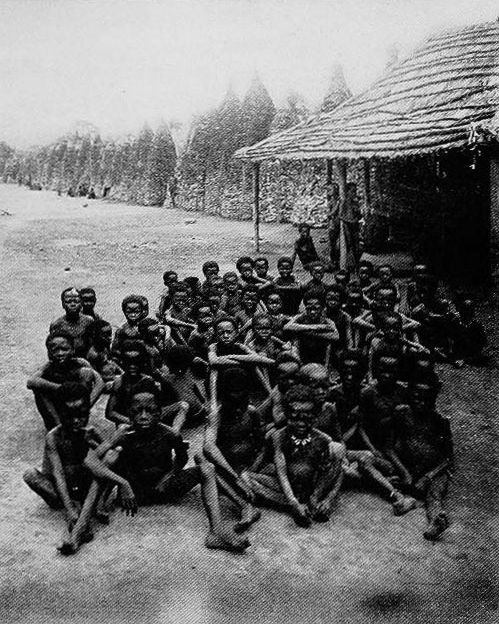

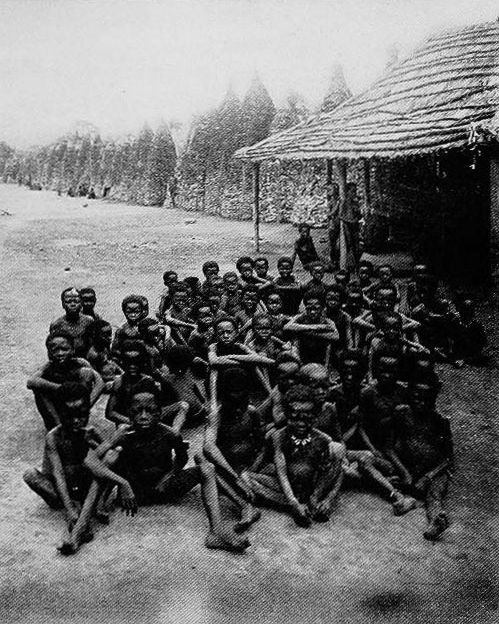

CHILDREN AT MOGANDJA, ARUWIMI RIVER