XIV.

February 2, 1907.

RETURNED from the Congo country and a year and more of contact with the dark natives, I find a curious and most disagreeable sensation has possession of me. I had often read and heard that other peoples regularly find the faces of white men terrifying and cruel. The Chinese, the Japanese, other peoples of Asia, all tell the same story.

The white man’s face is fierce and terrible. His great and prominent nose suggests the tearing beak of some bird of prey. His fierce face causes babes to cry, children to run in terror, grown folk to tremble. I had always been inclined to think that this feeling was individual and trifling; that it was solely due to strangeness and lack of contact. To-day I know better. Contrasted with the other faces of the world, the face of the fair white is terrible, fierce, and cruel. No doubt our intensity of purpose, our firmness and dislike of interference, our manner in walk and action, and in speech, all add to the effect. However that may be, both in Europe and our own land, after my visit to the blacks, I see the cruelty and fierceness of the white man’s face as I never would have believed was possible. For the first time, I can appreciate fully the feeling of the natives. The white man’s dreadful face is a prediction; where the fair white goes he devastates, destroys, depopulates. Witness America, Australia, and Van Diemen’s Land.

Morel’s “Red Rubber” contains an introductory chapter by Sir Harry Johnston. In it the ex-ruler of British Central Africa says the following: “A few words as to the logic of my own position as a critic of King Leopold’s rule on the Congo. I have been reminded, in some of the publications issued by the Congo government; that I have instituted a hut-tax in regions intrusted to my administration; that I have created crown lands which have become the property of the government; that as an agent of the government I have sold and leased portions of African soil to European traders; that I have favored, or at any rate have not condemned, the assumption by an African state of control over natural sources of wealth; that I have advocated measures which have installed Europeans as the master—for the time being—over the uncivilized negro or the semicivilized Somali, Arab, or Berber.”

It is true that Sir Harry Johnston has done all these things. They are things which, done by Belgium, are heinous in English eyes. He proceeds to justify them by their motive and their end. He aims to show a notable difference between these things as Belgian and as English. He seems to feel that the fact of a portion of the product of these acts being used to benefit the native is an ample excuse. But so long as (a) the judge of the value of the return made to the sufferer is the usurper, and not the recipient, there is no difference between a well-meaning overlord and a bloody-minded tyrant; and (b) as long as the taxed is not consulted and his permission is not gained for taxation, there is only injustice in its infliction, no matter for what end. Sir Harry uses the word “logic.” A logical argument leaves him and Leopold in precisely the same position with reference to the native.

Sir Harry closes his introduction with a strange and interesting statement. He says:

“The danger in this state of affairs lies in the ferment of hatred which is being created against the white race in general, by the agents of the king of Belgium, in the minds of the Congo negroes. The negro has a remarkably keen sense of justice. He recognizes in British Central Africa, in East Africa, in Nigeria, in South Africa, in Togoland, Dahomey, the Gold Coast, Sierra Leone, and Senegambia that, on the whole, though the white men ruling in those regions have made some mistakes and committed some crimes, have been guilty of some injustice, yet that the state of affairs they have brought into existence as regards the black man is one infinitely superior to that which preceded the arrival of the white man as a temporary ruler. Therefore, though there may be a rising here or a partial tumult there, the mass of the people increase and multiply with content and acquiesce in our tutelary position.

“Were it otherwise, any attempt at combination on their part would soon overwhelm us and extinguish our rule. Why, in the majority of cases, the soldiers with whom we keep them in subjection are of their own race. But unless some stop can be put to the misgovernment of the Congo region, I venture to warn those who are interested in African politics that a movement is already begun and is spreading fast which will unite the negroes against the white race, a movement which will prematurely stamp out the beginnings of the new civilization we are trying to implant, and against which movement, except so far as the actual coast line is concerned, the resources of men and money which Europe can put into the field will be powerless.”

This is curious and interesting. But it is scarcely logical or candid. Allow me to quote beside Sir Harry’s observations the following, taken from the papers of March 4, 1906:

“Sir Arthur Lawley, who has just been appointed governor of Madras, after devoting many years to the administration of the Transvaal, gave frank utterance the other day, before his departure from South Africa for India, to his conviction that ere long a great rising of the blacks against the whites will take place, extending all over the British colonies from the Cape to the Zambesi. Sir Arthur, who is recognized as an authority on all problems connected with the subject of native races, besides being a singularly level-headed man, spoke with profound earnestness when he explained in the course of the farewell address: ‘See to this question. For it is the greatest problem you have to face.’ And the solemn character of his valedictory warning was rendered additionally impressive in the knowledge that it was based upon information beyond all question.”

It is certain that the affairs in the Congo Free State have produced neither restlessness nor concerted action in British Africa. Why is it that on both sides of Southern Africa there have been recent outbreaks of turbulence? The natives, indeed, seem ungrateful for the benefits of English rule. Sir Arthur Lawley looks for a rising over the whole of British Africa, from the Cape to the Zambesi. In what way can the misgovernment of the Congo by its ruler have produced a condition so threatening? Both these gentlemen have reason, perhaps, for their fears of an outbreak, but as I have said, there is neither logic nor candor in attributing the present agitation in Southern Africa to King Leopold.

What really is the motive underlying the assault upon the Congo? What has maintained an agitation and a propaganda with apparently such disinterested aims? Personally, although I began my consideration of the question with a different belief, I consider it entirely political and selfish. Sir Harry Johnston naïvely says: “When I first visited the western regions of the Congo it was in the days of imperialism, when most young Britishers abroad could conceive of no better fate for an undeveloped country than to come under the British flag. The outcome of Stanley’s work seemed to me clear; it should be eventually the Britannicising of much of the Congo basin, perhaps in friendly agreement and partition of interests with France and Portugal.”

Unquestionably this notion of the proper solution of the question took possession of many minds in Great Britain at the same time. And England was never satisfied with the foundation of the Congo Free State as an independent nation.

A little further on, Sir Harry states that the British missionaries of that time were against such solution; they did not wish the taking over of the district by Great Britain. And why? “They anticipated troubles and bloodshed arising from any attempt on the part of Great Britain to subdue the vast and unknown regions of the Congo, even then clearly threatened by Arabs.” In other words, Britons at home would have been glad to have absorbed the Congo; Britons on the ground feared the trouble and bloodshed necessary. But now that the Belgians have borne the trouble and the bloodshed and paid the bills, Britain does not despise the plum. Indeed, Britain’s ambitions in Africa are magnificent. Why should she not absorb the entire continent? She has Egypt—temporarily—and shows no sign of relinquishing it; she has the Transvaal and the Orange Free State; how she picked a quarrel and how she seized them we all know. Now she could conveniently annex the Congo.

The missionaries in the Congo Free State are no doubt honest in saying, what they say on every possible occasion, that they do not wish England to take over the country; that they would prefer to have it stay in Belgian hands; that, however, they would have the Belgian government itself responsible instead of a single person. I believe them honest when they say this, but I think them self-deceived; I feel convinced that if the question was placed directly to them, “Shall England or Belgium govern the Congo?” and they knew that their answer would be decisive, their vote would be exceedingly one-sided and produce a change of masters. But the missionaries are not the British government; they do not shape the policies of the empire; their agitation may be useful to the scheming politician and may bring about results which they themselves had not intended. It is always the scheme of rulers and of parties to take advantage of the generous outbursts of sympathy and feeling of the masses for their selfish ends.

The missionaries and many of the prominent agitators in the propaganda against the Free State have said they would be satisfied if Belgium takes over the government. This statement never has seemed to me honest or candid. The agitators will not be suited if Belgium takes the Congo; I have said this all the time, and the incidents of the last few days have demonstrated the justness of my opinion. Already hostility to Belgian ownership is evident. It will increase. When the king really turns the Congo Free State government into Belgium’s hands the agitation will continue, complaints still will be made, and conditions will be much as formerly.

Great Britain never has been the friend of the Congo Free State; its birth thwarted her plans; its continuance threatens her commerce and interferes with expansion and with the carrying out of grand enterprises. In the earlier edition of his little book entitled “The Colonization of Africa,” Sir Harry Johnston spoke in high terms of the Congo Free State and the work which it was doing. In the later editions of the same book he retracts his words of praise; he quotes the atrocities and maladministration of the country. My quotation is not verbal, as for the moment I have not the book at hand, but he ends by saying something of this sort: “Belgium should rule the Congo Free State; it may safely be allowed to govern the greater portion of that territory.”

“The greater portion of the territory”—and what portion is it that Belgium perhaps cannot well govern? Of course, that district through which the Cape-to-Cairo Railroad would find its most convenient roadbed. If Great Britain can get that, we shall hear no more of Congo atrocities. There are two ways possible in which this district may be gained. If England can enlist our sympathy, our aid, our influence, she may bid defiance to Germany and France and seize from Leopold or from little Belgium so much of the Congo Free State as she considers necessary for her purpose, leaving the rest to the king or to his country.

If we are not to be inveigled into such assistance, she may, in time and by good diplomacy, come to an understanding with France and Germany for the partition of the Free State. Of course, in such event France would take that section which adjoins her territory, Germany would take the whole Kasai, which was first explored and visited by German travelers, and England would take the eastern portion, touching on Uganda and furnishing the best site for her desired railroad.

The same steamer which took me to the Congo carried a newly appointed British vice-consul to that country. On one occasion he detailed to a missionary friend his instructions as laid down in his commission. I was seated close by those in conversation, and no attempt was made on my part to overhear or on their part toward secrecy. His statement indicated that the prime object of his appointment was to make a careful examination of the Aruwimi River, to see whether its valley could be utilized for a railroad. The second of the four objects of his appointment was to secure as large a volume as possible of complaints from British subjects (blacks) resident in the Congo Free State. The third was to accumulate all possible information regarding atrocities upon the natives. These three, out of four, objects of his appointment seem to be most interesting and suggestive.

On a later occasion I was in company with this same gentleman. A missionary present had expressed anxiety that the report of the commission of inquiry and investigation should appear. It will be remembered that a considerable time elapsed between the return of the commission to Europe and the publishing of its report. After the missionary had expressed his anxiety for its appearance and to know its contents, the vice-consul remarked: “It makes no difference when the report appears; it makes no difference if it never appears; the British government has decided upon its course of action, and it will not be influenced by whatever the commission’s report may contain.” Comment upon this observation is superfluous.

Upon the Atlantic steamer which brought us from Antwerp to New York City there was a young Canadian returning from three years abroad. He knew that we had been in the Congo Free State, and on several occasions conversed with me about my journey. We had never referred to atrocities, nor conditions, nor politics. One day, with no particular reason in the preceding conversation for the statement, he said: “Of course, the Belgians will lose the Congo. We have got to have it. We must build the Cape-to-Cairo road. You know, we wanted the Transvaal. We found a way to get it; we have it. So we will find some way to get the Congo.”

Of course, this was the remark of a very young man. But the remarks of young men, wild and foolish though they often sound, usually voice the feelings and thoughts which older men cherish, but dare not speak.

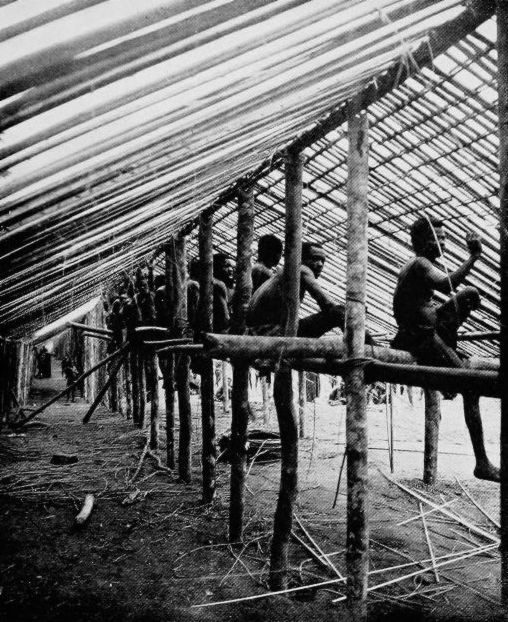

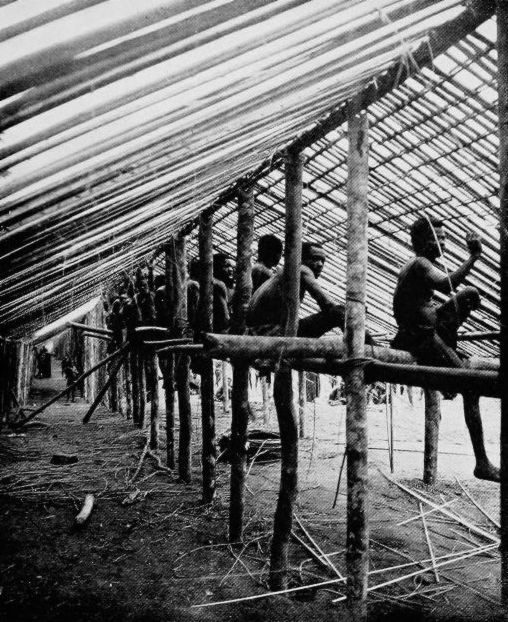

CONSTRUCTING NEW HOUSES AT BASOKO