CHAPTER XI

GLIMPSES AT DIVERS MEN OF THE SWORD

Aloyse was standing at the lower window of the house anxiously awaiting Gabriel's return. When she finally espied him, she raised to heaven her eyes filled with tears; but tears of happiness and gratitude they were this time.

She ran and opened the door with her own hands to her beloved master.

"God be praised that I see you once more, Monseigneur!" she cried. "Do you come from the Louvre? Have you seen the king?"

"Yes, I have seen him," Gabriel replied.

"Well?"

"Well, my good nurse, once more I have to wait."

"More waiting!" Aloyse exclaimed, wringing her hands. "Holy Virgin! it is very hard and very sad to wait."

"It would be impossible," said Gabriel, "if I had not work to do meanwhile. But I will work with a will, and thank God, I can beguile the tedium of the journey by thinking steadfastly of the goal."

He entered the parlor, and threw his mantle over the back of a couch.

He did not see Martin-Guerre, who was sitting in a corner plunged in deep reflections.

"Come, come, Martin, you sluggard, what are you about?" cried Dame Aloyse to the squire. "Can't you even help Monseigneur to take off his cloak?"

"Oh, pardon! pardon!" Martin exclaimed, rousing himself from his revery, and leaping from his seat.

"All right, Martin, don't disturb yourself," said Gabriel. "Aloyse, I wish you would not trouble poor Martin; his zeal and devotion are more necessary to me than ever at this moment, and I have some very serious matters to talk over with him."

Vicomte d'Exmès's slightest wish was sacred to Aloyse. She favored the squire with her sweetest smile, now that he was restored to grace, and discreetly left the room, to leave Gabriel more at liberty to say what was in his mind.

"Martin," said he, when they were alone, "what were you doing there? What were you thinking about so deeply?"

"Monseigneur," Martin-Guerre replied, "I was cudgelling my brain to solve in some degree the enigma of our friend this morning."

"Well, how have you succeeded?" asked Gabriel, smiling.

"Very indifferently, alas! Monseigneur. If I must confess it, I have been able to see nothing but darkness, however widely I have opened my eyes."

"But I told you, Martin, that I thought I could see something better than that."

"What is it, Monseigneur? I am almost dead trying to find out."

"The time has not come to tell you," said Gabriel.

"You are still devoted to me, Martin?"

"Does Monseigneur put that as a question?"

"No, Martin, I say it by way of commendation. Now I appeal to this devotion of which I speak. You must for a time forget yourself, forget the shadow which darkens your life, and which we will drive away hereafter. I promise you. But at present I need you, Martin."

"So much the better! so much the better! so much the better!" cried Martin-Guerre.

"But let us have no misunderstanding," said Gabriel. "I have need of your whole being, of your whole life, and all your manhood; are you willing to place yourself in my hands, to postpone your private troubles, and devote yourself solely to my fortunes?"

"Am I willing!" cried Martin; "why, Monseigneur, it is not only my duty to do so, but will be my greatest pleasure. By Saint Martin! I have been separated from you only too long, and I long to make up for lost time! Though there be a legion of Martin-Guerres inside my clothes, never fear, Monseigneur, I will laugh at them all. So long as you are standing there in front of me, I will see nobody but you in the world."

"Brave heart!" said Gabriel. "But you must consider, Martin, that the enterprise in which I ask you to engage is full of danger and pitfalls."

"Basta! I will leap over them!" said Martin, snapping his fingers carelessly.

"We shall hazard our lives a hundred times over, Martin."

"The higher the stake, the better the sport, Monseigneur."

"But this terrible game, once we engage in it, my friend, cannot be laid aside until it is finished."

"Then none but a fine player should take part in it," rejoined the squire, proudly.

"Not so fast!" said Gabriel; "despite all your resolution, you do not appreciate the formidable and extraordinary peril which may attend the almost superhuman conflict into which you and I are about to plunge; and after all, our efforts may be unrewarded,—remember that! Martin, consider all this carefully; the plan which I must carry out almost makes me afraid myself, when I examine it."

"Very good! Danger and I are old acquaintances," said Martin, with a very self-sufficient air; "and when one has had the honor of being hanged—"

"Martin," Gabriel interrupted, "we must defy the elements, exult in the tempest, laugh at the impossible!"

"Indeed we will!" said Martin-Guerre. "To tell the truth, Monseigneur, since my hanging, the days which have passed over my head have seemed to me like days of grace; and I am not inclined to find fault with the good Lord for that portion of the surplus which He has seen fit to allot to me. Whatever the merchant lets you have over and above the bargain, there is no need to account for; if you do, you are either an ingrate or a fool."

"Well, then, Martin, it's agreed, is it?" said Vicomte d'Exmès; "you will go with me and share my lot?"

"To hell itself, Monseigneur! so long as you don't ask me to set Satan at defiance, for I am a good Catholic."

"Have no fear on that score," said Gabriel. "By going with me you may perhaps endanger your welfare in this world, but not in the next."

"That is all that I care to know," rejoined Martin. "But is there nothing else than my life, Monseigneur, that you ask of me?"

"Yes," said Gabriel, smiling at the heroic ingenuousness of that question; "yes, indeed, Martin-Guerre, there is another great service that you must render me."

"What is it, Monseigneur?"

"I want you, as soon as possible,—this very day, if you can,—to find me a dozen or so companions of your mettle, daring and strong and resolute, who fear neither fire nor sword, who can endure hunger and thirst, heat and cold, who will obey like angels, and fight like devils. Can you do it?"

"That depends. Will they be well paid?" asked Martin.

"A piece of gold for every drop of their blood," said Gabriel. "My fortune causes me the least concern, alas! in the holy but perilous task which I must carry through to the end."

"At that price, Monseigneur," said the squire, "I will get together in two hours that number of dare-devils, who will not complain of their wounds, I assure you. In France, and in Paris especially, the supply of that sort of blackguard never fails. But in whose service are they to be?"

"In my own," said Vicomte d'Exmès. "I am going to make the campaign which I now have in mind as a volunteer, and not as captain of the Guards; so I need to have retainers of my own."

"Oh! if that is so, Monseigneur," said Martin, "I have right at my call, and ready at any moment, five or six of my old comrades in the Lorraine war. They are pining away, poor devils, since you dismissed them. How glad they will be to be under fire again with you for their leader! And so it is for yourself that I am to enlist recruits? Oh, well, then, I will present the full complement to you this evening."

"Very good," said Gabriel. "You must make it an essential condition of their employment that they be ready to leave Paris immediately, and to follow me wherever I go, without question or comment, and without even looking to see whether we are marching north or south."

"They will march toward glory and wealth, Monseigneur, with bandaged eyes."

"Well, then, I will reckon upon them and upon you, Martin. As for yourself, I will give you—"

"Let us not speak of that, Monseigneur," Martin interposed.

"On the contrary, we will speak of it. If we survive the fray, my brave fellow, I bind myself solemnly, here and now, to do for you what you will then have done for me, and in my turn to assist you against your enemies, never fear. Meanwhile, your hand, my faithful friend."

"Oh, Monseigneur!" Martin-Guerre exclaimed, respectfully kissing his master's extended hand.

"Come, now, Martin," continued Gabriel, "set about your quest at once. Discretion and courage! Now I must be alone for a time."

"Pardon! but will Monseigneur remain in the house?" asked Martin.

"Yes, until seven o'clock. I am not to go to the Louvre until eight."

"In that case," rejoined the squire, "I hope to be able to show you, before you leave, some specimens of the make up of your troop."

He saluted and left the room, as proud as a peacock, and already absorbed in his important commission.

Gabriel remained alone the rest of the day, studying the plan which Jean Peuquoy had handed him, making notes, and pacing thoughtfully up and down his apartment.

It was essential that he should be able to answer satisfactorily every objection that the Duc de Guise might raise.

He only broke the silence from time to time by repeating, with a firm voice and eager heart,—

"I will save you, dear father! My own Diane, I will save you!"

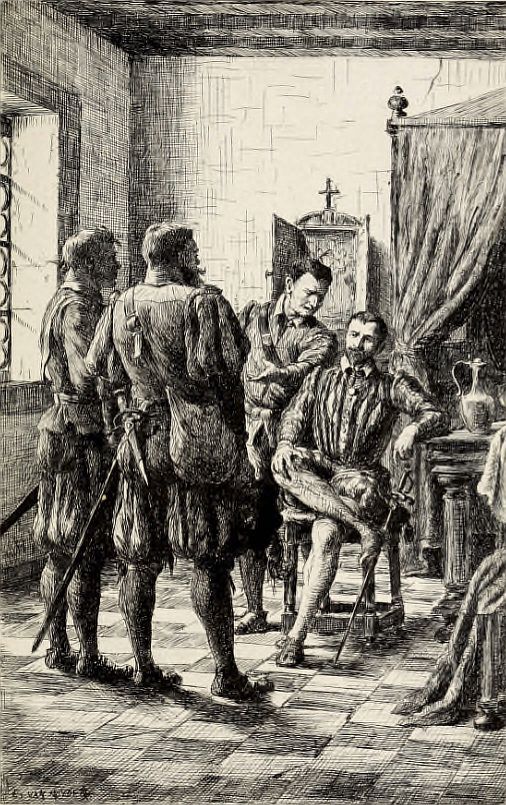

About six o'clock, Gabriel, yielding to the insistence of Aloyse, was just taking a little food, when Martin-Guerre entered, very serious and stately.

"Monseigneur," said he, "will it please you to receive six or seven of those who aspire to the honor of serving France and the king under your orders?"

"What! six or seven already?" cried Gabriel.

"Yes, six or seven who are strangers to you. Our old Metz companions will make up the twelve. They are all delighted to risk their necks for such a master as you, and accept any conditions that you choose to impose upon them."

"Upon my word, you have lost no time," said Vicomte d'Exmès. "Well, let me see the men; show them in."

"One at a time, shall I not?" rejoined Martin. "Monseigneur can form a better opinion of them then."

"Very well, one at a time," said Gabriel.

"One word more," added the squire. "I need not tell Monsieur le Vicomte that all these men are known to me either personally or through reliable information. Their dispositions and their peculiarities are varied; but they have one characteristic in common,—namely, a well-proved courage. I can answer to Monseigneur for that essential quality, if he will only be indulgent toward some little peccadilloes of no consequence."

After this preliminary discourse, Martin-Guerre left the room a moment, and returned almost immediately, followed by a tall fellow with a swarthy complexion, a reckless, clever face, and very quick of movement.

"Ambrosio," said Martin, introducing him.

"Ambrosio! that's a foreign name. Is he not a Frenchman?" asked Gabriel.

"Who knows?" said Ambrosio. "I was a foundling; and since I grew up, I have lived in the Pyrenees, one foot in France and the other in Spain; and, upon my word! I have, with a good heart, taken advantage of my double bar-sinister, without any ill feeling either against God or my mother."

"And how have you lived?" Gabriel asked.

"Well, it's just like this," said Ambrosio. "Being entirely impartial as between my two countries, I have always tried, to the best of my poor ability, to break down the barriers between them, and to open to each the advantages of the other, and by this free exchange of the gifts which each of them owes to Providence, to contribute, like a pious son, with all my power to their mutual prosperity."

"In a word," put in Martin-Guerre, "Ambrosio does a little smuggling."

"But," Ambrosio continued, "being a marked man by the Spanish as well as the French authorities, and unappreciated and hunted by my fellow-citizens on both sides of the Pyrenees at once, I concluded to evacuate the neighborhood, and come to Paris, the city which is overflowing with means of livelihood for brave men."

"Where Ambrosio will be happy," interjected Martin, "to place at the disposal of Vicomte d'Exmès his daring, his address, and his long experience of fatigue and danger."

"Ambrosio the smuggler, accepted!" said Gabriel. "Another!"

Ambrosio took his leave in great delight, giving place to a man of ascetic appearance and reserved manners, clad in a long dark cape, and with a rosary of great beads around his neck.

Martin-Guerre introduced him under the name of Lactance.

"Lactance," he added, "has already served under the orders of Monsieur de Coligny, who was sorry to lose him, and will give Monseigneur a very favorable account of him. But Lactance is a devout Catholic, and was very averse to serving under a commander who is tainted with heresy."

Lactance, without a word, signified his assent by motions of his head and hands to what Martin had said, who thereupon continued:—

"This pious veteran will, as his duty requires, put forth his best efforts to give satisfaction to Vicomte d'Exmès; but he asks that every facility may be granted him for the unrestricted and rigorous practice of those religious observances which his eternal welfare demands. Being compelled by the profession of arms which he has adopted and by his natural inclination to fight against his brothers in Jesus Christ, and to slay as many of them as possible, Lactance wisely considers it essential to atone for these unavoidable deeds of blood by stern self-chastisement. The more ferocious Lactance is in battle the more devout is he at Mass; and he despairs of counting the number of fasts and penances which have been imposed upon him for the dead and wounded whom he has sent before their time to the foot of the Lord's throne."

"Lactance the devotee, accepted!" said Gabriel, with a smile.

Lactance, still silent, bowed low, and went out, mumbling a grateful prayer to the Most High for having granted him the favor of being employed by so valiant a warrior.

After Lactance, Martin-Guerre brought forward, under the name of Yvonnet, a young man of medium height, of refined and distinguished features, and with small, well-cared-for hands. From his ruffles to his boots, his attire was not only scrupulously clean and neat, but even rather jaunty. He made a most courteous salutation to Gabriel, and stood before him in a position as graceful as it was elegant, lightly brushing off with his hand a few grains of dust from his right sleeve.

"This, Monseigneur, is the most determined fellow of them all," said Martin-Guerre. "Yvonnet, in a hand-to-hand contest, is like an unchained lion, whose course nothing can arrest; he will cut and thrust in a sort of frenzy. But he shines especially in an assault; he must always be the first to put his foot on the first ladder, and plant the first French banner on the enemy's walls."

"Why, he is a real hero, then!" said Gabriel.

"I do my best," rejoined Yvonnet, modestly; "and Monsieur Martin-Guerre, doubtless, rates my feeble efforts somewhat above their real worth."

"No; I only do you justice," said Martin, "and I will prove it by calling attention to your faults, now that I have praised your virtues. Yvonnet, Monseigneur, is the fearless devil that I have described only on the battlefield. To arouse his courage he must hear drums beating, arrows whistling, and cannon thundering; without those stimulants and in every-day life Yvonnet is retiring, easily moved, and nervous as a young girl. His sensitiveness demands the greatest delicacy; he doesn't like to remain alone in the darkness, he has a horror of mice and spiders, and frequently swoons for a mere scratch. His bellicose ardor, in fact, shows itself only when the smell of powder and the sight of blood intoxicate him."

"Never mind," said Gabriel; "as we propose to escort him to scenes of carnage, and not to a ball, Yvonnet the scrupulous is accepted."

Yvonnet saluted Vicomte d'Exmès according to all the rules of good-breeding, and took his leave, smiling and twirling the ends of his fine black mustache with his white hand.

Two huge blonds succeeded him, of quiet demeanor, and stiff as ramrods. One appeared to be about forty; the other could scarcely have passed his twenty-fifth year.

"Heinrich Scharfenstein, and Frantz Scharfenstein, his nephew," Martin-Guerre announced.

"The deuce! Who are these?" said Gabriel, in amazement. "Who are you, my good fellows?"

"Wir versteen nur ein wenig das franzosich" ("We only understand French a little"), said the elder of the giants.

"What?" asked Gabriel.

"We understand French poorly," the younger Colossus replied.

"They are German reîtres," said Martin-Guerre,—"in Italian, condottieri; in French, soldats. They sell their arms to the highest bidder, and hold their courage at a fair price. They have already served the Spaniards and the English; but the Spaniard didn't pay promptly enough, and the Briton haggled too much. Buy them, Monseigneur, and you will find you have made a great acquisition. They will never discuss an order, and will march up to the mouth of a cannon with unalterable sang-froid. Courage is with them a matter of bargain and sale; and provided that they receive their wages promptly, they will submit without a word of complaint to the dangerous, it may be fatal, chances of their kind of business."

"Well, I will retain these mechanics of glory," said Gabriel; "and for greater security I will pay them a month's wages in advance. But time presses; let me see the others."

Glimpses at Divers Men of the Sword.

The two German Goliaths, carrying their hands to their hats in soldierly style and as if mechanically, withdrew together, keeping step with perfect precision.

"The next is named Pilletrousse," said Martin; "here he is."

A sort of brigand, with a wild look about him and torn clothes, came in, swaying from side to side in an embarrassed way, eying Gabriel as if he were his judge.

"What makes you look so ashamed, Pilletrousse?" asked Martin, encouragingly. "Monseigneur here asked me to find some men of brave heart for him. You are a little more pronounced than the others; but really you have nothing to blush for."

Then he continued, addressing his master, in a serious tone:—

"Pilletrousse, Monseigneur, is what we call a routier. In the general war against the Spaniards and English he has up to this time fought on his own account. Pilletrousse haunts the high-roads, which are crowded nowadays with foreign robbers, and, in brief, he robs the robbers. As for his fellow-countrymen, he not only respects but protects them. Then, too, Pilletrousse fights and wins; he does not steal,—he lives on prize-money, not by theft. Nevertheless he has felt the necessity of confining his roving profession within more definite limits, and of harrying the enemies of France in less arbitrary fashion. Therefore he has eagerly accepted my suggestion that he should enrol himself under the banner of Vicomte d'Exmès."

"And I," said Gabriel, "will receive him on your statement, Martin-Guerre, on condition that he will no longer make the high-roads and by-ways the scene of his exploits, but will transfer it to fortified towns and the battle-field."

"Thank Monseigneur, blackguard! you are one of us," said Martin-Guerre to the routier, for whom, scamp though he was, he seemed to have a sort of weakness.

"Oh, yes, thank you, Monseigneur," said Pilletrousse, effusively. "I promise never again to fight single-handed against two or three, but always not less than ten."

"Very well," said Gabriel.

He who came after Pilletrousse was a pale fellow, of sad and careworn appearance, who seemed to look upon things in general with melancholy and discouragement. The finishing touch was put to the gloomy cast of his face by the seams and scars with which it was abundantly ornamented.

Martin-Guerre brought forward this the seventh and last of his recruits under the name of Malemort.

"Monseigneur le Vicomte d'Exmès," said he, "will be truly culpable if he rejects poor Malemort. He is, in truth, the victim of a sincere and profound passion for Bellona, to speak in mythological phrase. But this passion has heretofore been very unlucky. The poor fellow has a very pronounced and well-educated taste for war; he takes no pleasure except in fighting, and is only happy in the midst of great slaughter; but so far, alas! he has tasted happiness only with his lips. He has a way of plunging so blindly and madly into the thickest of the fray that he is always sure to receive some cut or slash at the first leap, which puts him hors de combat, and sends him to the hospital, where he lies during the remainder of the battle, groaning more over his enforced absence than from the pain of his wound. His body is one great scar; but he is vigorous yet, thank God!—he always gets well promptly. But he has to wait then for another opportunity. His long unsatisfied desire wears more upon him than the loss of all the blood he has so gloriously shed. Monseigneur, you must see that you ought not to deprive this melancholy warrior of a pleasure which may be productive of mutual benefit."

"Well, I accept Malemort very gladly, my dear Martin," said Gabriel.

A smile of satisfaction passed across Malemort's pale face. Hope caused his dull eyes to glisten; and he hastened to join his comrades with a much quicker step than when he entered the room.

"Are these all whom you have to present?" Gabriel asked his squire.

"Yes, Monseigneur; I have no others to offer at this moment. I hardly dared to hope that Monseigneur would accept them all."

"I should have been hard to suit indeed, had I not," said Gabriel; "your judgment is good and sure, Martin. Accept my congratulations upon your excellent selections."

"Well," said Martin-Guerre, modestly, "I do like to think that Malemort, Pilletrousse, the two Scharfensteins, Lactance, Yvonnet, and Ambrosio are not just the sort of fellows to be looked upon with contempt."

"I should think not!" said Gabriel. "What rough diamonds they are!"

"If Monseigneur," Martin continued, "should be willing to add to their number Landry, Chesnel, Aubriot, Contamine, and Balu, veterans of the war in Lorraine, I rather think that with Monseigneur at our head, and four or five of our people from here to wait upon us, we should have a pretty fine party to show to our friends, and better still, to our enemies."

"Yes, to be sure," said Gabriel; "arms and heads of iron! You must arm and equip these fine fellows with the least possible delay, Martin. But you have done enough for to-day. You have made good use of your time, my friend, and I thank you for it. My day, although it has been an active and painful one, is not yet ended."

"Where is Monseigneur going this evening?" asked Martin-Guerre.

"To the Louvre, to wait upon Monsieur de Guise, who expects me at eight o'clock," said Gabriel, rising. "But thanks to your prompt zeal, Martin, I hope that some of the difficulties which might have arisen in my interview with the duke are removed beforehand."

"Oh, I am very happy to know it, Monseigneur!"

"And so am I, Martin. You can't dream how necessary it is that I should succeed! Oh, I will succeed!"

The noble youth repeated in his heart as he walked to the door to take his way to the Louvre,—

"Yes, I will save you, dear father; my own Diane, I will save you!”