The rain poured down steadily till eight

o'clock, but when it ceased things were as bad for some time afterwards, sundry

small streams of water still dropping from every tree as we passed beneath. The

path, turned into a veritable quagmire with the rains, made marching anything

but pleasant. The sun shone at last, and as it began to gain power, things

became drier overhead, and our spirits rose accordingly. This was not

altogether a blessing, however, for the foetid vapours began to rise from the

swamps by which Kumassi is insulated; and the vile steamy mugginess was much

increased by the surface-water of the previous night's storm.

The broken rest

and general dampness affected the troops, though they stoically held out,

determined to reach the long looked for goal, and not give in with their object

in sight. Many, however, dropped by the way, thoroughly done, and the hammocks

were crammed. Still others could not keep up, and staggered along, vainly

trying not to fall out, while officers pluckily assisted their men by carrying

accoutrements, and giving an arm when needed.

Surgeon-Lieutenant

Spencer, though not well himself, relinquished his own hammock to a worn out

sick one, and not content with that, loaded himself with the accoutrements of

some of his men, who were just able to walk when thus relieved. That day's

march was not the only occasion that this young officer acted in a similar way,

and when the Medical Staff were reduced by sickness, he laboured day and night

tending the patients in his charge. It is such acts of devotion and

self-sacrifice as these that have ever made the British officer stand

pre-eminent in the annals of civilisation.

That march to

Kumassi proved to be another fine exhibition of the stamina and national pluck

which carries the Britisher through when other nations fail. Heavily equipped,

the troops had tramped towards Kumassi; in sweltering heat and dank night fogs,

and there was no malingering among them. Early and late the Tommies doggedly

pressed on, defying the fever and not giving in till they dropped by the

wayside, thoroughly overcome.

Then! at last …

KUMASSI - the proud and dreaded capital of Ashanti!

Major Baden Powell's force had worked its

way by different paths through the bush, capturing many armed Ashanti spies on

the way. The main road into the town was narrow but fairly good, and led

through a dense patch of high jungle grass, fringed with medicine heaps. There

were also many graves strewn with fetish images, and rotting vultures tied by

the neck to the head posts.

Suddenly a

thunder of drums could be heard, but still the scouts warily advanced. Major

Gordon and Captain Williams cut their way through the bush, and entered the

town by the Kokofu road on the right flank, and a party of Bekwais forced a

passage in the same way on the left. The main advance party consisted of Major

Piggott bearing the Union Jack on his Soudan Lance, Major Baden-Powell and

Captain Graham with the scouts and levies, Captain Mitchell with a company of

Houssas, and their drums and fifes and the Expedition’s Political Officer,

Captain Stewart. The levies were followed by a small party of four Engineers;

Sergeant Lowe, Corporal Dale, and Sappers Richardson and Rubery, with the reel

of cable, which they paid out and fixed as they marched. The wire was in and

working at an early hour; a fresh feather in the cap of the smart

telegraphists, who had slaved from morn till night in getting the cable laid

from the coast. Shortly after the scouts had arrived, the two flank parties

appeared, and piquets were immediately posted on all the approaches to the

Palaver Square, where the levies halted at 8.20 a.m., the flag being firmly

planted in the centre of the market.

The drumming

increased, and at last King Prempeh, with his chiefs and hundreds of followers,

was seen advancing. They made no show of resistance: the King seated himself on

his throne, or raised dais, in one corner of the clearing, while the chiefs and

followers ranged themselves in dense lines on the two sides of the square.

Colonel Stopford's gallant boys heard the thunder of drums in the distance, and

mistaking it for firing, eagerly pressed forward. Fatigue and fever were alike

forgotten as they broke into a trot, eager for the fray, but the troops were

doomed to disappointment when they drew nearer, and the true nature of the

sounds was revealed.

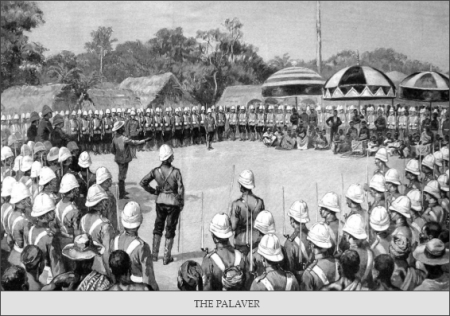

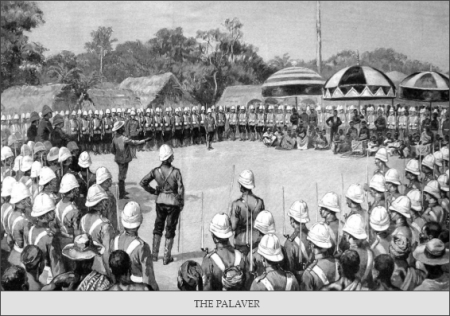

Close behind

the “Specials” came the Houssas with their seven-pounders, then Sir Francis

Scott and his Staff, followed by the West Yorkshire Regiment and their

carriers. As each company of troops arrived they were drawn up in the Palaver

Square, and soon a long string of hammocks wended their way onward to the Field

Hospital on the outskirts of the town, bearing many a poor fellow with aching

head and burning frame. The baggage column then poured in with line after line

of carriers, and it was three o'clock before the whole force was drawn up and

dismissed to quarters. The Houssa Band made an attempt to play the troops in,

and among other appropriate airs, the strains of “Home, Sweet Home,” floated through

the trees, as if in irony at the dirty surroundings.

Viewed from a

distance, the long rows of enormous coloured umbrellas resembled the line of

round-abouts in Barnet pleasure fair, with far more infernal din than in that

English orgie. The chiefs and petty kings were arranged in rotation, from the

King himself, ranging gradually downward according to rank, till the minor

chiefs took up their position by the side of the road leading into the town.

The least powerful chief had one big umbrella and a small group of dependents

and slaves, with a couple or so of drums and tom-toms; but higher up the line,

the fallowings grew with the importance of their master, and the number of

musicians likewise increased.

Near Prempeh,

the Kings of the surrounding Ashanti dependencies were placed, with their

swords of state and fetish dancers; but little attention beyond a passing

glance was paid to these groups, for on the built throne sat Prempeh and all

his royal gathering in choice barbaric array.

Was that oily,

peevish-looking object the monarch whose name alone made the surrounding tribes

tremble? It seemed impossible, but yes, it was he, and in a state of ludicrous

funk.

He was sitting

with his back half turned to the square, but now and again he glanced round furtively

at the troops formed up there. He wore a black crown, heavily worked with gold,

a silken robe and sandals. Suspended from his body and wrists were various

fetish charms, while behind him hung a dried lemur as a special fetish. He was

seated on an ordinary brass-studded chair, which was placed on the top of the

tier of baked clay forming the throne. The fabled stool of solid gold was not

to be found, and had been removed to a safe distance, long before the troops

entered the capital.

Seated on the

left of King Prempeh, was the Queen Mother, smiling and jabbering, with an air

of nonchalance that contrasted strongly with the marked concern exhibited by

her puny-hearted son. Though her face wore a hard, cruel expression, she had

regular features, and would have been good looking had her appearance been less

sinister. Round her were perched a numerous train of women, decently and

cleanly dressed, but their shaved heads and flat oily faces gave them a most

repulsive look. Prempeh's Aunt, swathed in a gaudy wrapper of silk, sat among

them, enjoying a gnaw of chew-stick, and grinning at the white men who

approached the throne. Like the Queen Mother, the demeanour of these women was

one of absolute indifference, though the faces of the sterner sex were livid with

fear.

The lower parts

of the throne were filled by prime ministers, advisers, sword bearers,

executioners, and criers, in every description of barbaric apparel. On the

outside of the circle, slaves bearing huge plaited fans, kept a constant

current of air directed toward the King. The throne, with its numerous

occupants, was sheltered by immense and gaudy umbrellas held aloft by gigantic

Swefis, captured in a raid by Samory, or some other manhunter, and sent to

slavery in Kumassi.

Grouped in a

large circle round the throne were some hundreds of Prempeh's minions,

under-executioners, lesser ministers of the household, and slaves. In the

centre of the circle, three hideous fetish dwarfs, in little red shirts,

capered about, while seated in a group on the right were Prempeh's own personal

attendants. These boys and men were protected by various fetish laws, and wore

as a badge, a small hair cap surmounted with a mortar board of gold. They

seemed to enjoy their position immensely, but as their paramount privilege

consisted in being sacrificed on the death of the King, to accompany him to the

next world, the honour of such a post was highly enigmatical.

Surrounding the

royal circle were the musicians, and the din was absolutely ear-splitting.

Enormous war drums, bedecked with skulls, dried eyes, ears and other portions

of the body, boomed out in deafening thunder as they were vigorously hammered

by perspiring slaves, tom-toms were untiringly thumped, a continuous clanging

was kept up by means of iron rings, and hollow metallic vessels knocked

together, while a separate band of slaves added to the infernal din by

monotonous roars from elephants' tusks, carefully graded to play two alternate

notes. Each lusty tooter could have put a steam siren in the shade, the first

deep roar resembling a hundred hoarse steam-boat whistles, followed by the

shriller shrieking of an army of tugboats in mortal agony.

Drawn up in

line were the native levies, with their long guns, every whit as proud as kings

themselves. Major Baden-Powell had done wonders with these men, who in four

weeks were transformed from a horde of savages into a disciplined force.

Right opposite

Prempeh were his revolted subjects, the Bekwais, and many a glance of hate went

across from those dusky ranks, to be returned by glances of envy from many of

the petty Kings, who would gladly have thrown off Prempeh's rule in the same

manner, had they dared. Rushing about from King to chief in great perturbation

of spirit, were the two Ansahs. They found playing at king-making very pleasant

when masquerading in London, but fraught with considerable danger and anxiety

in Ashanti.

The King had

ascended his throne early in the morning, and sat right on till five o'clock,

watching the arrival of the dreaded white men. The Royal family all seemed of a

superior race to the remainder of their subjects; in fact, they bore little

resemblance to the surrounding Ashantis, being better looking, and of a much

lighter colour. The reason of this is not far to seek, for in Ashanti as in other

countries in Africa, the Kings have as many wives as they like, picked from all

classes of society; but blue blood is not the necessary qualification for a

royal marriage; the indispensable endowment is good looks. The royal sons may

marry pretty women, the royal ladies the best looking men they can find.

Prempeh's

mother was very fickle in that respect; in fact, she was a veritable female

Bluebeard. It is stated that at various times she had taken unto herself fifty

husbands, all of whom were executed by her orders, until Prempeh's father came

on the scene, and the offspring was considered comely enough to ascend the

stool. The Kumassi eligibles must have, figuratively speaking, trembled in

their shoes at an amorous glance from that female dragon. She so thoroughly

turned the matrimonial market into a lottery, in which a blank meant death,

though her speedy vengeance also would unerringly descend on those who failed

to enter the lists when told.

The troops were

quietly dismissed to their quarters, and still Prempeh held state reception in

all barbaric pomp and splendour; but it was his last, though little did he

realise how completely his power would be overthrown, without a chance on his

part to fight for it. The Ashanti rulers may be skilled in wily statecraft, but

they proved no match for European diplomacy with its far-reaching arms.

About one

o'clock the reception had begun with a weird dance of executioners and dwarfs

round the throne. Three dancers in long flowing robes twirled and leaped in a

mazy serpentine fling, till they dropped thoroughly exhausted, to be followed

by others. The chief executioner also gave a solo dance, accompanied by the

most diabolical leers and suggestive gestures, as he furiously brandished his

huge beheading knife, accompanying each wild flourish with a series of blood

curdling whoops and yells.

The various

kings and chiefs next approached to pay homage to the plenipotent monarch,

while the din waxed louder than ever. Each chief advanced in turn, with all his

followers, down a long lane formed through Prempeh's courtiers. The royal crier

then sprang to his feet, and, in Ashanti epics, extolled his master's virtues

and prowess.

The monarch, if

he were flattered by these eulogies, could not fail to be wearied by their

repetition hour after hour. During this uproar, the headman of the visiting

chief was also shouting and gesticulating, as if to call attention to the

marvellous qualities of his own master, and when this pantomine had gone far

enough, sudden silence fell on everyone; even the drums were hushed, while the

chief advanced slowly, as if entranced, with his eyes glued on Prempeh's face,

and prostrating himself on each step of the throne, he at last cringed full

length at the monarch's feet. The King, after a mock show of deliberation,

extended his hand, which the prostrate chief gingerly clasped between his own

extended palms. Bowing his head, he shook with emotion, as if thoroughly

overwhelmed by the ineffable bliss of holding the oily paw of the cruel nigger

despot, and so great were the transports of joy that he could not let that hand

go. Prempeh's prime minister pushed him with his foot, and his own headmen

dragged at his robe. No! He could not tear himself away. The tugging grew more

forcible, till, with mournful countenance and much rolling of eyes, he

sorrowfully arose and prepared to descend. Then the silence was broken as

suddenly as it commenced, and the din started again with redoubled vigour. The

Chief moved down one step, and stopped again. The wrench was too great! He

hesitated, then advanced a stage lower, stopped undecided, while his waiting

attendants beckoned and howled for him to come. It was impossible, and he

sorrowfully shook his head from side to side; but, with a vigorous and

unceremonious shove, the prime minister sent him flying off the step into the

outstretched arms of his people.

The

hypocritical old wretch dragged his robe securely round his shoulders, heaved a

great sigh of relief at having got through his part of the business, and

marched off with his followers. Another immediately took his place, and exactly

the same ceremony was gone through, and kings and chiefs succeeded each other

in this performance, in all its details; though, at heart, those cringing

Negroes were cursing the very existence of the monarch they were professing to

revere.

After seeing a

dozen or more go through the same form I turned to inspect the city; I say

“city” advisedly, but mud heap would have been better. It certainly boasted of

many regular and wide streets with fairly built wattle houses on each side; but

the very roads were defiled, and the place was a mass of festering pollution.

The much vaunted capital was a combined filth heap and charnel house.

The town stands

in a large clearing at the foot of a hill, and appears to have been larger than

at present, notably on the east side, which was once an extensive suburb, but

now is deserted. It is almost surrounded by a swamp; but under proper sanitary

conditions the place might be made fairly inhabitable, though the misty

exhalations from the marshes envelop the town at night in a thick fog which is

not conducive to health.

Disgusted with

the filthy hole, I turned into quarters in one of the clay bedaubed dwellings.

Outside they are substantially built, but once inside, the compound was a

quagmire of polluted mud and filth, round which the veranda-like chambers

opened; and in that state of foul squalor had the Ashantis lived like pigs.

Heaps of this accumulated offal had to be carted away before the places were

fit for European occupation, and then only with abundant disinfectant was

existence possible. Everyone suffered more or less from sore throat, which was

due to the vile smell and dampness.

Lieutenant

Pritchard, R.E., was indefatigable in his endeavours to make things pleasant.

This young Engineer had exhibited great tact and energy throughout the march,

and had been right forward with the advance; done a full share of duty when his

superiors were stricken with fever, and came through with flying colours,

though, unfortunately, he was seized with malaria after Kumassi was invested

and his work practically done.

Captain Blunt

ranged his guns so to have full sweep across the Palaver Square and its

approaches, and Major Baden-Powell pushed through the town to Bantama, and held

all the roads from that direction. The Special Service Corps and West Yorks

were quartered in two of the many separate districts into which the town was

divided by stretches of dense elephant grass and corn patches.

At five

o'clock, Sir Francis Scott and all the officers of the Expeditionary Force

seated themselves in a semi-circle on the square, while Captain Stewart and his

interpreter went to tell the King that the Commander was ready to see him. Some

of the chiefs blustered a little after Captain Stewart had gone, but the Ansahs

finally persuaded Prempeh to pluck up his failing spirits and comply, which he

did with a bad grace.

The huge umbrellas began to bob and twist,

and drums were beaten as the whole of that vast assemblage got into motion, and

came slowly across the square toward the Commander-in-chief. The two Ansahs

acted as prompters, going through the motions in dumb show, while the lesser

chiefs passed, salaaming with outstretched hand to each officer in succession

down the line. These chiefs were succeeded by the more important men and their

followers, and finally Prempeh himself, with a large nut in his mouth, as a

special fetish charm to guard against the wiles of the white man, was half

dragged past between two attendants. He looked remarkably like a fat over-grown

youngster, sucking a bull's-eye, but ready for a good cry at being taken to

school.

A more abject

picture of pusillanimity could never be painted than of that despot as he

passed, cringing and trembling, down the line. He afterwards advanced and shook

hands with Sir Francis Scott and Major Piggott, who must have both felt

overwhelmed by the honour. Sir Francis then addressed a few words to him

through the interpreter: “Tell him, I am glad to see him here, and that there has

been no fighting. I think he and his people have shown very good sense in not

resisting the advance of the Queen's forces. I don't want any of those noises

and disturbances at night, as we had when I was here twenty-two years ago in

the last war. He must tell his people to bring things and form a market, and

everything will be paid for. The town must be kept clean. White men cannot live

in such filth, and the long grass will have to be cut down. We want good order,

and I have told my people that they must not plunder anyone. The Governor, who

is Her Majesty's representative, will be here to-morrow. He will arrange a day

for palaver, und you must make your submission to him in native custom. That is

all. I wish you a good evening.”

The white

troops were respectfully standing in a line behind the officers to witness the

proceedings, but the native carriers, with less deference, clustered round the

Staff, obstructing the view of the soldiers behind. Little notice was taken of

this until Prempeh approached, when curiosity overcame other scruples, and

there was a rush to get a closer view of the King. The Ashantis instantly

divined treachery, and were panic stricken; for a moment the utmost confusion

reigned. Their black hearts, imputing their own methods to others, suspected a

ruse; they thought they had been betrayed, and the men were going to fall upon

them; but their apprehensions were soon quieted when the troops stopped on the

edge of the crowd, where they could feast their eyes on that flabby, yellow,

but royal countenance.

When the

palaver was over, Prempeh again resumed his seat on the throne, but many chiefs

had taken their departure, eager to get clear away. Evidently Prempeh thought

he was well out of the wood, and nothing would now be done by the force except

to install a Resident and march away satisfied with any amount of flimsy

promises, which the Ashantis could as easily break as heretofore.

Most of the

officers and men had retired to the European side of the town when the royal

litter arrived, and the King descended from his perch to be borne in triumph to

the Palace. In tropical regions there is no twilight; the sun had set, and

sudden darkness descended when the royal procession was formed. The King and

many of his adherents had been fortifying their nerves, and were fairly on the

way of being “beastly drunk,” as a West Yorkshireman remarked.

There were only

three white men in the vicinity, but Prempeh insisted on shaking hands with

all; I can feel the grip of that clammy paw again, as I write. A start was then

made for the Palace, and the weird appearance of that barbaric state procession

by torchlight, baffles description. The musicians marched first, some of the

enormous drums being carried between four slaves, and beaten by drummers in

rear. Hundreds of torches were lit, while the crowd of nobles, courtiers,

captains, citizens, and slaves, went mad with transports of joy, excitement,

and rum. The purport of all this enthusiasm was echoed in their cry: ''Prempeh!

Prempeh! Your fetish has proved too strong for the white man! No power on earth

can prevail against thee!”

They leaped,

they squirmed, shouted and screamed, directing all their frenzied motions to

the royal litter, from which little could be seen except a crowned head; and a

puny hand waving in acknowledgment to the roaring plaudits. Wearing European

costume, and patent boots fit for Bond Street, were the two Ansah Princes. They

squirmed and squealed and shouted with the rest, looking perfectly ridiculous

in their civilised attire.

Prince Christian

and Major Piggott appeared on a bank watching the proceedings: both Ansahs

danced furiously to the rear of the litter, and then walked quietly behind with

the greatest nonchalance; but directly the procession turned the corner,

thinking they were free from European observation, they again danced and yelled

with redoubled vigour: the noble savages!

As soon as

darkness fell, piquets were stationed in all directions, guarding every

approach. Spies from Kumassi had entered the British lines the day before, and

reported that the Ashantis did not want to fight, and would not resist if the

English only wanted to establish a Church and a Resident; but if they

interfered with Prempeh, soldiers were ready in the bush. Also that plenty of

powder had been distributed in the town, and the spies thought they had

undermined the Palace and Palaver Square in case of emergency. Ten thousand

warriors also had been collected in the capital a few days before our entry.

No doubt exists

that had not the Ansahs arrived with reports of the strength of the advancing

English, which they greatly exaggerated, the Ashantis would have offered a

spirited resistance at the entrance to Kumassi, when they found that no amount

of subterfuge and false promise would keep back the invader. The wiser counsels

of the Ansahs had prevailed, and the warriors were removed to the bush, still

ready to answer to the calls of their chiefs if needed.

Strict orders

had been issued against looting, and also to respect the sacred fetish temples

or hovels, which were all marked by white cards so that no one should

unwittingly enter and defile the sanctity of mud and sticks. The town was

littered with fetish heaps, shrines, images, clay pans, bottles, and other

symbolic fetish tokens, and many a sly kick was given by the Houssas to these

charm pots.

Many of the

houses in the principal street were highly embellished, the walls being

stuccoed in red, and finished in white; but with all this decoration there was

still the filth and stench, and the hundreds of carriers were at once set to

work to thoroughly cleanse and clear the end of the town occupied by the

troops. Beyond an occasional drumming, all was quiet in the native quarter, and

the streets were thronged as usual by the proletarian Ashantis and slaves, though

the upper classes did not show themselves much.