On Saturday, the 18th, Governor Maxwell

arrived, and he was accorded a full official reception. The troops were

paraded, and as His Excellency entered the Square, a 14-gun salute was fired by

the Artillery. He addressed a few words to the force, complimenting them on the

excellent way they had surmounted all obstacles and gained their object.

Captain Stewart

had intimated to Prempeh that he must tender his submission on Monday, January

20th but on Sunday there was a distant desultory drumming, and Ashantis became

more scarce in the town. It was evident that some movement was in the air.

On Sunday

evening, a palaver was held in the palace, the chiefs being hastily summoned,

and it was thought that this was a ruse to get them together to endeavour to slip

away in the night, get clear, collect their forces and attempt an attack on

Kumassi when most of the troops had been withdrawn. They well knew that the

white soldiers would have to leave before the rains set in, and may have

thought that eventually they would be left in peace to return to Kumassi, and

resume their life, in the old sweet way, as in 1874, when all troops, both

white and coloured, were withdrawn.

To guard

against arty escape, the jungle was cleared right round the palace, and a

cordon of the native levy drawn round after dark. The Palace Garden joined the

bush at the back, and a secret footpath led through the swamp beyond. The

piquets soon secured many prisoners, who emerged from the palace to reconnoitre

on the various roads, only to find each was barred. The palace people grew

anxious when the various spies did not return, and one of the Ansahs came out

to see what was in the wind, and was found on the secret pathway.

At about three

o'clock the Queen Mother emerged from the palace with torches, and a long train

of attendants, and passed unconsciously right through the outposts, but she was

not stopped. She and her people went to her own private residence, which was

quietly surrounded as soon as she was domiciled. Several chiefs were also captured

during the night, trying to slip away; but Prempeh had either got an inkling of

affairs, or did not mean to bolt, as he did not attempt to leave in person. The

various prisoners were released at daylight, when everything was in readiness

for the final act to take place.

The King had

been told to appear at 8 o'clock, with all his chiefs, on the palaver ground.

The white troops formed up on the square at 7 a.m.; and the Houssas, followed

by the long lines of levies, had arrived from their quarters just before. After

a weary wait, it seemed that Prempeh did not mean to come, so Captain Stewart

and the interpreter went to fetch him. Major Barker also took a company of the

Special Service Corps to strengthen the cordon round the palace, making escape

impossible. Captain Stewart went in alone and told the King he must come at

once, or he would take him by force.

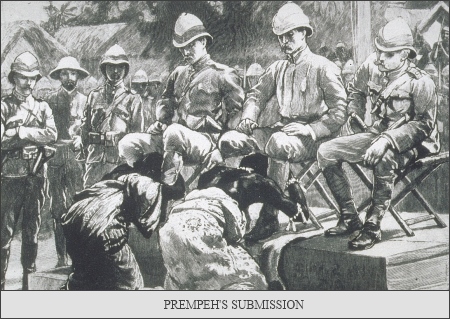

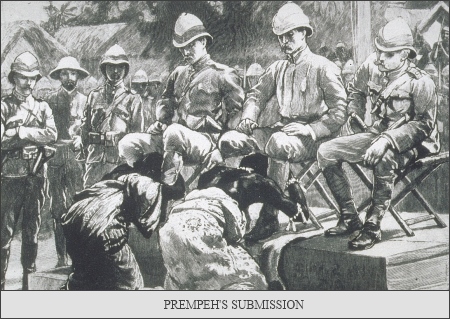

There was a

beating of one solitary drum, as the King entered his litter, and with a little

delay, the Queen Mother joined the royal procession, which slowly wended its

way across the clearing, into the square formed by the troops. Prempeh was

accompanied by his chiefs, and followed by a large procession of guards,

soldiers, slaves and attendants; but with a quick flank movement the Houssas

cut this crowd away from their leaders, and umbrellas and stools, bearers and

attendants, were soon flying in every direction. The Queen Mother took a seat

on her son's left; the chiefs and a few select servants ranging themselves in a

long line facing Governor Maxwell, Sir Francis Scott, and Colonel Kempster.

These officers were seated on an improvised dais of biscuit boxes, surrounded

by the remaining officers of the Staff.

One chief was

still absent, but presently the disobedient old rascal came in sight with his

followers, escorted by a body of Houssas, sent to fetch him. These troops moved

along at a quick rate; an undignified and unceremonious way for his chief-ship

to make his debut, and one which he bitterly resented. He was pushed and

jostled by his followers pressed in rear by the gallant little Houssas; and

then his attendants were all turned roughly aside, and he had to walk into the

square unattended. He turned indignantly to expostulate, but a muscular

sergeant added insult to injury, by seizing a stool and squatting him forcibly

down upon it. The palaver then commenced.

Mr. Vroom, the

Native Commissioner, acted as interpreter, and through him the conditions of

the treaty were given to the Ashantis; but it had to be again repeated by the

royal linguist to Prempeh, who could not demean himself by listening to the

stranger's voice. Governor Maxwell reminded the King of his direct refusal to

the ultimatums dispatched to him; further, that he sent Envoys to England, in

direct opposition to orders; for they were told that all negotiations must be

made to the Governor on the coast.

His Excellency

went on to say that no article of our last treaty with Ashanti had been kept.

They had made no attempt to pay the war indemnity, and it was still owing.

Human sacrifices were to have been abolished, but they had still gone on. No

road had been kept clear through the bush to the coast, which was another

express stipulation of that treaty. However, the British Government had no wish

to depose Prempeh if he would agree to the following conditions: He must make

his submission in native fashion; and pay an indemnity of 50,000 ounces of gold

dust. On this basis, His Excellency was now ready to receive the submission of

the King and the Queen Mother.

Prempeh

hesitated. It was a terrible blow to the prestige of that haughty despot, to

whom “all the princes of the earth bowed down,” to thus humiliate himself in

the presence of those white men and his own people. He looked sheepish, toying

with his fetish ornaments, and ready to cry with mortification. Albert Ansah

stepped up and held a whispered consultation with him. Then, quietly slipping

off his sandals, the King arose, removed his circlet, and he and the Queen

Mother reluctantly walked over to prostrate themselves before the Governor, and

embrace his feet.

The scene was a most striking one. The

heavy masses of foliage, that solid square of red coats and glistening

bayonets, the Artillery drawn up ready for any emergency, the black bodies of

the native levies, resting on their long guns in the background, while inside

the square the Ashantis sat as if turned to stone, as Mother and Son, whose

word was a matter of life and death, and whose slightest move constituted a

command which all obeyed, were thus forced to humble themselves in sight of the

assembled thousands.

It was indeed a

fall to the pride of that plenipotent monarch and his royal mother, to whom

many a tortured victim had pleaded in vain for life, and at whose feet the very

chiefs had to prostrate themselves, before they dared speak.

A perfect hush

fell on the assembled multitude, and even the irrepressible natives were

silenced as the King and his royal mother knelt, and tendered their submission;

then rose to their feet, thoroughly humiliated and confounded, and returned to

their people.

Prempeh

collected himself, and being prompted by the Ansahs, again rose, exclaiming in

a clear voice, “I now claim the protection of the Queen of England.” The chiefs

seconded this remark with a resonant cry of “Yeo! Yeo! Yeo!” - “Good! Good!

Good!”

The Governor

reminded him that only one of the conditions had been fulfilled. He was now

ready to receive the indemnity which had been promised. Oh, yes! The King knew

that quite well and he would be most pleased to pay it. Unfortunately, the

treasury was not full just then, so he would pay 340 bendas, i.e., 680 ounces

of gold, and pay the rest by instalments.

The Governor

replied: “It is absurd to think that a man able to send envoys to England, has

only that small amount in his treasury. Ashanti shall have British protection,

but first British demands must be complied with. The King has been told that he

must pay the indemnity, and he must provide the whole or a large part of the

amount at once. The Ashantis have proved that their word cannot be trusted, and

they have repeatedly promised to pay the last indemnity, but had never

fulfilled that promise. The King must this time give me ample security.”

Prempeh, with a deprecatory gesture, said he would pay in time.

The Governor

rejoined: “Then the King, the Queen Mother, the King's father, his two uncles,

his brother, the two War Chiefs, and the Kings of Mampon, Ejesu, and Ofesu,

will be taken as prisoners to the Coast. They will be treated with due

respect.”

Had a

thunderbolt burst in their midst, the Ashantis could not have been more amazed.

Consternation was depicted on every countenance, and all sat transfixed for a

moment, then leaping to their feet, the chiefs begged that Prempeh should not

be taken from them.

Kokofuku,

pointing to the Ansahs, who stood by, looking half amused, half astonished,

shouted angrily, “And what about those men, who have brought this trouble upon

our heads?” The Governor replied: “The Ansahs will be arrested as criminals and

taken to the coast on a charge of forgery.”

The signal was

instantly given; Captain Donovan of the Colonial Service stepped out and

handcuffed the two Princes; several officers and warrant officers, previously

appointed, drew their swords and formed up as escort to the Ashanti King and

Chiefs. The denouement was startling and complete, and one almost expected to

see the curtain fall on that dramatic scene, amid the plaudits of the audience

and hammering from the gods.

The captives

were marched, shortly after, to a house prepared for their reception, and the

Ansahs were incarcerated in the Houssas' Guard room. The Princes were struck

dumb at their reception. Words cannot describe John's expression of mingled

hate, fear, rage and astonishment. Thus was the crafty Negro foiled; a man of

undoubted talent, whose cleverness and education, if directed properly, might

have made him a leading light on the Gold Coast. Born in Kumassi, he was taken

as a babe to Cape Coast Castle. He was well educated, took an oath of

allegiance, and entered the Gold Coast Rifle Corps. As a youth he fought for

the English against his own country in 1874, and obtaining a medal. Then he

constantly had intrigues with Kumassi, and was dismissed from the Public

Service of the Gold Coast Colony. With his younger brother Albert, who had

returned to Kumassi, he worked hard for his own ends, and these two educated

princes finely duped their more ignorant Ashanti countrymen. When they, as

envoys, arrived in England, they immediately began to work in their own

interests, selling concessions to which they had no right, and forging

documents purporting to come from King Prempeh himself. As a specimen of their

cool effrontery, they wrote the following letter in London, and forwarded it to

the Queen, but needless to add, their character and fame had gone before, and

they were not received.

- - -

To

the Most Gracious and Illustrious Sovereign,

Victoria,

Queen of Great Britain and Ireland.

Kwaku

Dua III., King of Ashanti, wisheth health and prosperity.

We pray Your Most Gracious Majesty to

know that we have appointed our trusty and well beloved, grandson, Prince John

Ossoo Ansah, son of the late Prince Ansah, of Ashanti, on our behalf to lay

before your Majesty divers matters affecting the good estate of our kingdom and

the well-being of our subjects, with full power for the said Prince Ansah as

our ambassador extraordinary and minister plenipotentiary to negotiate and

conclude all such treaties relating to the furtherance of trade and all matters

therewith connected as your Majesty shall be pleased to entertain. We therefore

pray that your Majesty will be pleased to receive the said Prince Ansah on our

behalf and to accord to him your Majesty's most royal favour.

Given

at our Court at Kumassi this 8th day of September, 1894.

Kwaku

Dua III.,

King

of Ashanti. My X Mark

- - -

Two companies of the West Yorkshire

Regiment, under Captain H. Walker, immediately took possession of the Palace.

The cordon had not been withdrawn, so no one could leave. All the doors were

barred, however, on the inside, and there was a hum of many voices to be heard

as the troops approached. One company, therefore, formed round to strengthen

the cordon of levies, while the others, under the guidance of Major

Baden-Powell, proceeded to make an entrance by a side door. Owing to the rumour

that the Palace was undermined, the main entrance was not selected. The side

door was burst in, and opened into a large deserted courtyard. Another painted

door was then broken down, and the troops dashed in among some hundreds of

natives.

The work of

collecting the valuables in the palace was next proceeded with. Looting the

palace of a king of great reputed opulence was tempting work; but though a

great many valuables were seized, there was no fabulous wealth discovered as in

the palaces looted in India and China. The treasure collected, only consisted

of the richly worked head-dress of the King, also rings, gold trinkets and

charms, gold hilted swords, &c, &c., with hundreds of articles of small

value.

The celebrated

Golden Stool of Ashanti, the solid gold crown, and many other almost historical

relics of great intrinsic worth, had been previously removed to a place of

safety, and secretly hidden where, perhaps, no eye will ever penetrate. An

Ashanti custom was to bury the treasure in the bush in time of war, the slaves

occupied in the task being then beheaded. From reports, this had been done just

before the troops invested this capital of mud and murder. The seized spoil was

deposited in a heap outside Headquarters, and soon formed a large pile, a great

portion of the articles being of the most common-place description. Gorgeous

State umbrellas, enormous kinkassies or wardrums, brass-studded chairs,

beautifully carved stools, European and native swords, native spears, Ashanti

daggers and knives, executioners' blades and torture instruments, brass studded

cases, leather fetish caps, silken and cotton cloths, execution stools with

recent blood stains, valuable old English chinaware, common table knives, large

glass vases, carved wooden sandals, silk and gingham pillows of down and soft

cotton, a few tusks, ivory pieces for playing “po” and drafts, a few bottles of

brandy, common blunderbusses, old flint locks, a few Sniders, and so on ad

infinitum.

Fetish was

represented by hundreds of charms of every size, shape, and description, from

the common slaves' ju-ju of plaited straw to the elaborately worked charms of

chased gold or leopard and lion skin, with human blood on the sacred

inscription inside as a fancied panacea, of far-reaching power, to cure every

disease, destroy an enemy, and grant the wearer a perfect immunity from any

ills the flesh or spirit is heir to. The writing in these charms is usually

burnt or written on cloth or paper; but I saw one inscription beautifully

branded on a dry strip of bamboo bark in Burmese style. The writing resembles

that of the Sanskrit, the formation of the figures being identical, but as I am

not an authority on the subject, I am unable to say if it is the same in every

respect.

There was not a

large number of guns discovered, in fact, few weapons of any description. The

armed men had made off to the bush, and were no doubt only awaiting the call of

their leaders, now safely ensconced, with a file or two of Houssa bayonets

between them and their warriors. Among the loot were some horrible cloths

including a woman's robe, saturated with blood, and other evidences of very

recent sacrifices were not wanting.