On Wednesday afternoon, December 18th, we

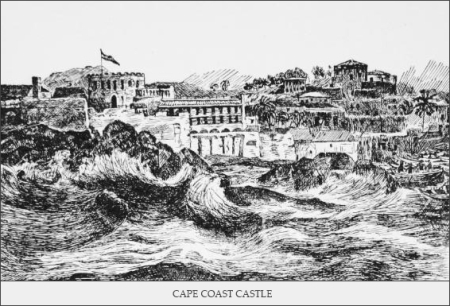

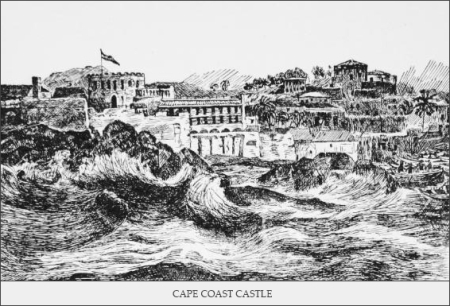

had the welcome news that our destination was in sight. After passing the white

walls of the castle and town perched on high ground, the ramparts of Cape Coast

Castle were plainly visible, and at six o'clock we dropped anchor about

three-quarters of a mile from the shore. It was too late to land that evening,

but we were immediately surrounded by boats and canoes whose occupants were

soon floundering in the water, scrambling for ship's biscuits thrown from the

troop-deck.

The town of

Cape Coast, as we viewed it that night, lit up by the last rays of the setting

sun, made a scene of striking grandeur. Built on a solid rock is the castle,

consisting of battlements and turrets, and with the main building and tower in

the centre, while a blue sea rolls in great waves, which rise in crested walls

of water as they break on the rock at the base. Low hills surround the town,

while the white walls of the fort gleam from the heights beyond. The little

whitewashed church and mission houses on the sea front, and the substantial

houses of the traders, form a strong contrast to the native quarter, where the

mass of square flat-roofed houses of red clay stand perched in every

conceivable position below. Small clumps of palm trees on the east border a

mass of half-ruined houses of the same description which stand tottering on the

top of a green bank whose sandy base is ever washed by the waves as they break

with a continuous roar. Behind the town, and extending right to the water's

edge on either side of it, rise green masses of luxuriant vegetation, forming

the ridge of dense African forest that stretches away to the interior. As the

sun set in all its tropical splendour, throwing a crimson tint over the whole,

the most prosaic could not fail to be struck with the rare and romantic beauty

of the scene that would enrapture an artist and make a spring poet rave.

Anchored off the castle were the gunboats

“Racoon” and “Magpie,” rolling incessantly in the heavy swell, which must make

things very unpleasant on board in those narrow quarters. The life of Naval

officers and men, shut up in the confines of their floating home off the

African coast, must be terribly monotonous, as they lie day after day

continuously rolling with no outlook, save perhaps a few mud huts and

impenetrable bush, and their resources for any kind of amusement are

necessarily limited.

We were a merry

party at dinner that night, the last we should spend on board. There were the

usual speeches and leave-takings of officials going to posts lower down the

coast; a couple of naval officers came over from the “Magpie” to dine, and we

thus ended what had been a most pleasant voyage, thanks chiefly to Captain

Jones and the other officers of the ship who had taken every care of our

creature comforts throughout the voyage.

During the

evening a boat came from the shore, and as it reached the ship there was a cry

of recognition. “Here's Piggott!” An officer came on board in quiet serge

patrols, but those cleanly-cut features, clear fearless eyes lit by a gleam of

humour, the firm mouth and determined chin, revealed a striking personality. It

was Major Piggott, hero of a dozen fights, and with more active service records

than any two officers on the expedition, though there were old campaigners

there, and no feather-bed soldiers.

We were up

betimes next morning, and after a hurried breakfast, clambered over the side into

the waiting surf boats with our traps. We were paddled vigorously ashore by

twelve muscular Fantees, who sat six aside on the gunwale, paddle in hand,

giving a combined stroke as each wave lifted us on the crest, and watching

their opportunity, the boat was rushed ashore on the curling top of a large

breaker, the next wave dashing over the boat and drenching us. A dozen naked

blacks were at hand, and seated on the shoulders of two gigantic specimens, I

found myself at last deposited high and dry on the shore of Cape Coast Castle.

The scene on the sand was a particularly animated one, as boat after boat

arrived in quick succession, loaded with stores from the “Loanda,” and as soon

as one boat's load was landed, a gang of carriers, many of them young girls and

boys, had each put a box on their head and carried it into the Castle

courtyard, while super-intending the work were Supply Officers, standing in the

blazing sun with parched faces and dried lips. Once on shore the heat begins to

tell, the sun beating down with merciless ferocity, and woe betide that

foolhardy person who exposes himself without suitable head-gear, as sun-stroke

is then inevitable to a European.

Cape Coast

Castle was in an uproar with the preparations for the advance on Kumassi. I had

heard before I arrived that the place was the most filthy and neglected town

known under a civilised government, and therefore did not expect to find things

particularly flourishing. Such an assertion as the above is perhaps too

sweeping to describe the present state of the town, but even now it would rank

among the worst types of places with all the improvements which have taken

place since 1874. The town has been in English hands now for two hundred and

thirty years, and yet, beyond a few minor improvements, it remains as it was,

with the addition of a few larger and more substantial houses, built by traders

who have settled there. The town lies in the hollows at the base of three

hills, the centre immediately behind the Castle being occupied by the Government

House, chief trading houses, post office, church, mission-house and schools,

and on each side over various little undulations and hollows are massed the

squalid mud hovels of the Fanti population proper.

The Fantis are

the inhabitants of the town of Cape Coast and its immediate neighbourhood. They

are a fine-looking tribe, but about as cowardly a race of blackguards as could

well be found, and with all their bombast, the mention of an Ashanti makes them

tremble. As allies, they are perfectly useless for fighting, and are greatly

despised in consequence by the tyrants on the northern boundary. Their outward

fetish worship is not very powerful now, but still flourishes, one curious

fetish being the mass of rock called “Tahara” on which the Castle stands. At

regular periods this is washed and swept by the women, and offerings are piled

up on it.

To the east of

the town rises Connor's Hill, which was used as a hospital and sanatorium for

the troops, and from the top, by the white wooden houses and marquees forming

the hospital wards, a fine view is obtainable. In front is the mighty expanse

of the ever-rolling Atlantic, to the right stands the Victoria tower, and

nearer at hand on the top of the centre hill, Fort William, a round whitewashed

little place, resembling a Martello tower, and now used chiefly as a

lighthouse. Behind the fort is Prospect House, while all around, closing right

into the very outskirts of the town, is the bush, so thick and tangled as to be

almost impenetrable.

The little

water obtainable is stored in wells outside the town, and there is no system of

drainage in Cape Coast Castle. There are 12,000 inhabitants, none over clean,

and many living in a horrible state of filth; so imagine what condition a place

in ordinary latitudes would be in under such circumstances. Added to that there

is the intense heat, and not a breath of air stirring in the lower parts of the

native quarter, where the stench is unbearable. There is one large surface

drain cut right through the centre of the town; but, whatever use it may be in

the wet season, in the dry it is simply a convenient repository for all the

filth and offal that the natives wish to get rid of. The authorities do what

they can to prevent the depositing of offensive matter in the streets, and a strict

ordinance is in force by which all delinquents caught in the act may be heavily

fined. This may have a little effect in bettering matters, but the natives

easily evade the law by keeping the refuse in their hovels all day and throwing

it outside at night when darkness has set in. With sanitation in such a state

in an otherwise deadly climate, small wonder that Europeans sicken and die if

they stay in the place any length of time. Undoubtedly a very great deal could

be done to improve matters, but the authorities are not alone to blame, as the

lack of water is a great defect, and the filthy habits of the natives, if

restricted, cannot be altered by law, however rigidly enforced.

On landing at

Cape Coast, on December 19th, I found the whole place in a glorious state of

bustle and confusion. Long lines of carriers were taking stores from the shore

to the castle. Fresh gangs were being loaded and sent off up country to Mansu,

where the intermediate depot on the road to the Prah was formed. Everything was

in a very forward state, though the first contingent had arrived less than a

fortnight before, and Sir Francis Scott and his staff had only landed a few

days previously.

Colonel Scott

had certainly an efficient staff of officers under his command for Special

Service. He himself served in the last Ashanti war, and was also in the Crimea

and through the Indian Mutiny. In 1892 he was in command of the expedition

against the Jebus on the West Coast, and is at present Inspector General of the

Gold Coast Constabulary or Houssas. Colonel Kempster, D.S.O., Second in

Command, has served in the Egyptian Army, and was also in the Bechuanaland

Expedition. Major Belfield, Chief Staff Officer, had seen no previous war

service, but he is a Staff College man, and has a very high reputation.

Surgeon-Colonel Taylor, Principal Medical Officer to the force, when he was

selected for Ashanti, had only recently returned from special service with the

Japanese Army, during their late war with China. He was present at the capture

of Port Arthur and Wei-hai-wei, and he was for some years on the staff of Lord

Roberts, in India. Lieutenant Colonel Ward, A.S.C, Assistant Adjutant-General,

served in the Soudan. Major Piggott was in Zululand and served in the

Transvaal, but it was in Egypt and the Soudan that he made his name and gained

a list of honours in the many engagements he passed through, and in 1886 he was

second in command in the expedition against the Yonnes. Major Piggott and

Prince Christian Victor were aides-de-camp to Sir Francis Scott. The latter

volunteered his services, and his appointment was sanctioned by the Queen. He

has seen service in India, where much of his military career was spent. Captain

Larrymore, Adjutant of the Gold Coast Constabulary, has a medal for the Jebu expedition,

and was eminently fitted for aide-de-camp, as his duties on the coast have

brought him into close contact with Sir Francis, and he is thoroughly

acquainted with the tribes in West Africa, both on the coast and in the

interior.

Apropos of

Captain Larrymore's connection with Sir Francis Scott, a story of that young

officer's pluck may not be out of place. In February, 1892, while on a tour of

inspection, Sir Francis Scott and Captain Larrymore, with a small party of

Houssas, called at Asuom, where there was much excitement among the natives

over the death of their King. After a long march in the heat of the day, the

officers settled down in a native shanty to rest, having put their men into

quarters.

Sir Francis was

suddenly disturbed by a great clamour, and going to the door of the hut he saw

his troops surrounded by an armed, howling mob, mad with drink. The Houssas had

formed into line and were loading their rifles, while the natives, who numbered

a thousand or more, had loaded also, and in another minute shots would have

been exchanged, when the little force must have been annihilated. Captain

Larrymore, however, dressed only in a suit of pyjamas, rushed in between

the-two bodies of men with his umbrella open. He gave orders to his men to

unload and go into the hut, while he quietly stood, umbrella in hand,

confronting the horde of savages. Such prompt presence of mind had its effect.

Quiet was restored, and the natives, after yelling considerably, retired. Had

the Captain seized his arms and rushed out showing signs of alarm, the niggers

would have instantly opened fire, and no one would have been left to tell the

tale; but such quiet pluck is not without an effect even on the dark minds of

African savages.

Another

digression may be of interest in connection with Captain Larrymore, who had

recently returned from the Koranza country in the interior. While there he

gleaned further information about the existence of a white tribe in the

interior of Africa. He found it was an accepted tradition among the Houssa

tribes that on a strip of the desert to the north-east, there lived a tribe of

white men. As this desert was dangerous, attempts had been made by the Koranza

people to avoid it, by passing through these white men's country, but they were

found to be so fierce that the dangers of the desert were preferred to the

hostility of this tribe. He afterwards met a Mohammedan priest and Hadji; a man

of great integrity, who had been to Mecca and had seen one of this white tribe

on his return journey. Captain Larrymore suggested that the man was simply a

light-coloured Arab, but the Hadji said “Oh, no! I saw him close at hand. He

had light hair and blue eyes, exactly as you have, and was armed with a bow and

arrows.” This region is practically unknown to European travellers, but for

some years, reports have constantly been brought down by the natives as to the

existence of this white race, and there seems now to be substantial grounds for

believing there is a foundation for their story.

Things were

kept very lively in the Castle by the constant arrival of various kings who

came in from the surrounding districts with their followers to act as carriers.

Each arrival was announced by a fearful uproar; shouting, singing, horn

blowing, and beating of tom-toms; the rank of each chief and the number of his

followers being easily decided by the amount of din made. As an officer

pertinently remarked, “You could first hear them, then smell them, and

afterwards see them,” as they marched down the main street to the Castle. The

present power of many of these kings and chiefs is purely nominal, so a special

ordinance was brought into force, conferring upon them the power to enrol their

able-bodied subjects for service with the expedition, and under this enactment,

all kings and chiefs were liable to heavy fine for neglect in collecting their

men, and their subjects also liable to punishment for refusing to obey orders.

This ordinance

quite did away with the stern necessities of martial law, and was a sort of

compromise between that, and making service optional, in which case the

required number of carriers would never have been collected. The arrangement

proved satisfactory in every respect, causing great excitement among the

natives as soon as it was published, and they willingly rallied round their

chiefs. The Governor certainly acted wisely in reaching the people through

their own head-men, who were thus backed by the authority of the Government.

Their loyalty to the British is only prompted by fear, but they still keep up a

semblance of their former devotion to their kings, whose legal power, in most

cases, is absolutely nil.

The case of the

Accra King Tackie may be cited as an example of this. In 1881, he was a

prisoner at Elmina Castle, and his people steadfastly refused to join the

expedition then being formed, unless Tackie were released. When he was

ultimately set free, he had no legal control left over his tribe, and latterly

he seemed to have so allowed his moral influence to wane, that his power had

practically ceased to exist. When a new enactment order came into force,

however, and temporary power was again vested in him, the Accras rushed en

masse to their chief, and he suddenly found himself in a position of perfect

authority over his people, whose latent instincts of loyalty were stirred to

the utmost. They arrived at Cape Coast Castle on the 21st in full force, amid

scenes of great excitement. It was so long since the Accra people had been

regaled by a Royal Procession, that they determined to make the most of it, working

themselves into a state of enthusiasm bordering on frenzy. The poor old king,

finding the excitement infectious, was so beside himself with his newly-found

power, that he indulged in a penny bottle of palm-wine from a roadside

merchant, and after drinking a carefully measured half, he distributed the

remainder among the head-men while his people danced round, wildly shouting

most extravagant and adulatory encomiums to the dusky monarch, amid a deafening

accompaniment of drums, tom-toms and horns.

In the streets

of Cape Coast, the one topic was the war; and the niggers were all squatting on

their hams, gravely discussing the ins-and-outs, and probable consequences

thereof. Many of them remember the last war, and a few, who had served in some

capacity in '74 and obtained a medal, were proudly exhibiting the precious bit

of silver, pinned on an old European coat or shirt donned for the occasion.

Meanwhile, up country, things were being pushed forward. Major Baden-Powell was

at Prahsu with his levies, and rest camps were being formed at intervals along

the road to the Prah River. Stores were being rapidly sent on ahead, and it was

evident that, when the white troops arrived, everything would be in readiness

for a rapid advance to the frontier, beyond which, progress must be slow and

difficult.

An

ever-absorbing difficulty on the West Coast is to keep the water in tolerable

order. Just outside Cape Coast are large wells, or closed underground

reservoirs of puddled clay, with a small opening to the surface, and a more

substantially made tank in the town. These wells are filled in the rainy

season, the water being stored for subsequent use, but after standing for some

time in such a climate, it is totally unfit for European consumption, and is

doubtless a great cause of sickness among white men on the coast, though the

natives apparently suffer no ill effects from it. Many of the officials and

traders have private tanks to store their water, in which it is kept free from

contamination, but nothing can prevent it becoming stagnant and tainted by the

surrounding unwholesome influences.

There are a

great many pretentious looking stores in the town, but most of the commodities

consist of old stuff, shipped from England or Germany, calculated to catch the

Negro eye, and little can be purchased that is of service to a European.

English money is now more freely circulated, though many places of business

still retain their scales for weighing the gold-dust which, until recently,

formed the staple currency. Coppers are looked at with disdain, the smallest

article being threepence, and thus the modest silver bit is in great demand.

The Market

stands on the front, but it is only a corrugated iron shelter with open sides

and no fittings. The bush people flock down with their supplies, and barter is

much carried on with their stock and coast commodities. There is an air of

bustle and activity there all day long as the dusky vendors, dressed in gaudy

wraps of Manchester print, ply their trade, while perspiring women stagger

round with a heavy load balanced on their heads and a nodding brown babe or two

tied behind. Thus loaded, they thread their way through the crowd, vigorously

pushing the sale of their stock of bananas and plantains.

The horse is a

greater curiosity in Cape Coast than an elephant at home, for in the narrow

environs of the town there is little use for them, though the total absence of

suitable forage alone forms an insuperable barrier to their introduction. There

are a few light hand-carts or buggies occasionally to be seen flying through

the streets, drawn by half-a-dozen stalwart Fantis; the occupants being some

white official or trader going to make a call, or a haughty gentleman of

colour, who looks disdainfully on the pedestrian canaille around him.

The approved method

of travelling is by hammock, for this means of locomotion is available, and

fairly comfortable, under the most difficult conditions of road, through forest

or swamp, where all other mode of transport is impossible. The hammock is slung

on a stout bamboo with cross pieces fixed at each end, and an awning over the

whole. The four bearers stand, one at each corner, and placing the ends of the

cross pieces on their heads, walk with a swinging stride, the weight being

evenly distributed and the hammock hanging suspended between them. The jolting

is trying at first, and until confidence is gained, the nervous inmate feels at

every step one end will slip from the bearers head, in which case a nasty fall

is inevitable, but so practised do these hammock boys become that they rarely

make a false step, and if one trips, his hand is up instantly to keep the load

firm till he recovers his equilibrium.

One half of the

West India contingent was encamped on Connor's Hill, the remainder being sent

forward to Mansu. Many of the former daily reported sick, and no doubt they

suffered as much from fever as any of the white, troops, though the attacks

were shorter and had less effect. Many of the cases were trivial, and I am

afraid the close proximity of the hospital gave vent to a great deal of

malingering among these lazy Negroes, in the hope of getting admitted as a

patient, with a few additional luxuries and no duty to perform.

On December

21st, the smart detachment of Artillery non-commissioned officers, under

Captain Benson, left to take charge of the Houssa battery at Mansu. The

butchers and bakers of the Army Service Corps also started, under Sergeant

Major Sparks, to get field ovens built, and a batch of fresh bread ready for

the troops when they marched up country.

The

accommodation in the Castle was severely taxed, many officers having to find

quarters in the Wesleyan Mission House. The school-rooms afforded shelter for

the men of the Engineers, who made themselves as comfortable as possible on the

stone floor, and if the bed were hard, at least it was dry and cool. One of the

most amusing sights in the Castle was the massing and numbering of carriers as

they were formed into gangs. Large cases of police armlets, with numbers

attached, were sent out, and the possession of one of these gaudy bandages was

the cause of much inward joy and gratification to the dusky burden bearers.

Each native lost no time in strapping on his number, there being little fear of

his discarding the valued insignia of office as enrolled carrier to the Queen,

and the work was much facilitated thereby, for each man's number was always

visible, denoting his position and gang without difficulty or palaver.

The

indefatigable Army Service Corps certainly earned themselves fresh laurels for

the efficient arrangements of transport, and before the troops had landed,

there were 11,000 loads of supplies safely deposited at Prahsu; a feat of no

small magnitude, over an indifferent track of seventy-three miles.

The underlying

impression of the visitor, though, is that the more that is seen of Cape Coast

and its surroundings, the greater wonder is created as to how little the

Government has done for the town and its inhabitants. True, there is a fairly

efficient force of native police, who walk about, baton in hand, ready to crack

the skull of any offending nigger. There are a few oil lamps sprinkled down one

or two of the principal streets, but any other road or track is left in total

darkness, and from one end of the town to the other there are numerous holes

and pitfalls into which any traveller, who has the temerity to walk abroad

after dark, is sure to come to grief. Then the stench and pollution in many of

these slums are a disgrace to any town whose inhabitants profess to be under

the British Flag.