The Franklin’s Tale

If the Wife of Bath’s Tale offers a challenge to the established order regarding marriage and sovereignty, it is The Franklin’s Tale which offers the last word. This is the tale where trouthe is the absolute key. It is noteworthy that, in this tale, even marriage is treated in part as a friendship136 — meaning that it contains many sorts of trouthe, not merely fidelity.

And yet, the ending isn’t really happy. Everyone in it has been tested, sternly, and all come out honorably — but they don’t get what they want.

As with the other Chaucerian romances, the tale predates Chaucer himself — the tale is somewhat similar to elements of Boccaccio’s Filocolo although the parallel is not very close.137 The motivating element of the “rash promise” is a very common one in folklore, although the case in the Franklin’s Tale is not very close to some of the frequently-cited (alleged) parallels.138

If the Clerk’s Tale is a story of one woman’s trouthe, and the Wife of Bath’s Tale is of two people’s trouthe, the Franklin’s Tale involves three cases139 — arguably four. The Franklin begins by announcing that

Thise olde gentl Britouns in hir dayes

Of diverse aventures maden layes,

Rymeyed in hir firste Briton tongue....140

In other words, the tale will be a “Breton Lay,” meaning a (probably musical) metrical romance in the style of the romances of Brittany, not Britain — although in fact none have survived in Breton;141 the Breton Lays known to us are all French or English. English or not, they represent an important influence on Chaucer, since the romances, of which the Breton Lays were in many ways the best example, seem to have been the only substantial English literary sources Chaucer would have had before him142 — if he had any English inspiration, they were it. Chaucer’s own description of the type is brief, but we have a much fuller Middle English definition of the Breton Lays, which like Chaucer’s description comes itself from one of the lays:

We redyn ofte and fynde ywryte,

As clerkes don us to wyte,

The layes that ben of harpyng

Ben yfounde of frely thing.

Sum ben of wele, and sum of wo,

And sum of ioy and merthe also;

Sum of trechery, and sum of gyle,

And sum of happes þat fallen by whyle;

Sum of bourdys, and sum of rybaudry,

And sum þer ben of the feyré.

Of alle þing þat men may se,

Moost o loue forsoþe þey be.

In Brytayn þis layes arne ywryte,

Furst yfounde and forþe ygete,

Of aventures þat fillen by dayes,

Wherof Brytouns made her layes.143

The above doesn’t really tell us much — in essence, it says that the Breton Lays are simply romances. But they tended to be a particular kind of romance: “[T]he lays strove for many of the same effects as the modern short story. In length they had to be brief enough to be heard through on a single occasion.... In subject, though here the maker had a wide variety of lore to draw upon, they had to center upon some single character who must be brought through a series of critical situations to a happy end. In treatment they had to be dramatic.”144 Their brevity is shown by the tales of Marie de France, who created the earliest surviving Breton Lays; the longest of them has only 1184 lines and the shortest a tenth that.145 Marie’s tales are rather unlike the standard romance in another way: they deal heavily with relationships. “[T]he characteristic of Marie’s view of love seems to be an almost invariable association with suffering.”146 The Lays do not, like many romances, tell primarily of adventures; they deal with the problems of lovers and friends.147 Which, of course, is the subject of the Franklin’s Tale, which makes me wonder if that might not be what Chaucer meant by a Breton Lay.148

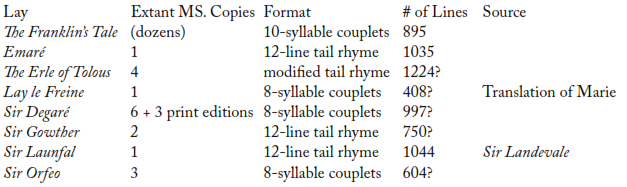

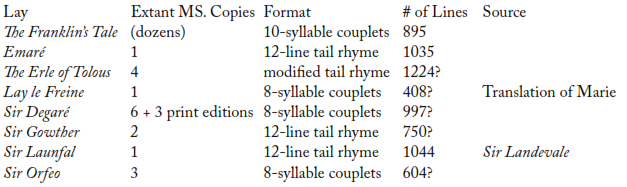

There are only eight Breton Lays extant in Middle English,149 summarized below:150

Thus in length the Franklin’s Tale is not atypical of the English Breton Lays — but in approach it is quite different, in part because it is in decasyllabic couplets (all the others are either in octosyllabic couplets or in tail rhyme) but also because there really is no main character — four characters share the stage almost equally.

The tale opens with the knight Arveragus courting Dorigen. They agree to wed. Out of respect for her, he agrees that he will not exercise sovereignty over her (although she will make a show of respect for him in public):151

Of his free wyl he swoor hire as a knyght

That nevere in al his lyf he, day ne nyght,

Ne sholde upon hym take no maistrie

Agayn hir wyl, ne kithe hire jalousie,

But hire obeye, and folwe hir wyl in al.152

But then, like many other knights trying to build a reputation, he leaves Brittany for England to win fame.

In his absence, a squire named Aurelius courts Dorigen. She has no interest in him, and is truly devoted to Arveragus, but rather than simply bid Aurelius go away, she offers a deal: If he can remove all the rocks on the coast of Brittany (which make it dangerous for Arveragus to return home), she will grant him her love. The task seems impossible, but so strong is Aurelius’s desire that he sets out to find someone who can do it — and finds a Clerk of Orleans who is strong enough in magic to perform the feat for a few weeks. Aurelius offers him a thousand pounds153 if he can pull off the feat.154

By now Arveragus is safely home — and Aurelius, helped by his clerk, makes the rocks vanish and comes to claim his prize. Dorigen, desperate,155 explains the situation to Arveragus. Although they could perhaps dodge the issue,156 they face it squarely. A lesser man might conclude that Dorigen had already, in effect, played him false. Arveragus, drawing her out, realizes that she had no desire but to be true to him.157 But, noble man that he is, declares that she must do as she has promised, for “Trouthe is the hyeste thyng that man may kepe.”158 It is not easy for him — in his long discussion, this statement “is the last line of a speech in which he is desperately trying to rouse his wife from her misery, by not letting her see his own agony of mind. But, as he says it, his agony breaks through, and ‘with that word he brast anon to weep.’”159 Still, trouthe is binding. So she goes to Aurelius, and miserably prepares to keep her promise. Aurelius, recognizing Dorigen’s love for Arveragus and the couple’s nobility, shows his own by releasing her of her promise. He then goes to the clerk and prepares to make his payment. And the Clerk, seeing Aurelius’s own nobility, in turn releases Aurelius of his oath.

It is a beautiful ending — “The Franklin’s is one of the gentlest, most gracious, smiling tales ever spoken with unhumorous dignity”160 — but some have argued that it papers over the problem. It’s true that a less honorable person could exploit all these generous people — but it also shows the power of trouthe. Dorigen made a rash promise, violating her trouthe to her husband — and came near to paying a high price. But it is interesting that, when confronted with Aurelius’s miracle, she had three choices. She could have ignored her promise. She could have submitted to Aurelius secretly without telling her husband. Or she could tell Arveragus. She chose the difficult thing, but the troutheful thing; she told Arveragus. He told her to keep her word — in other words, to fulfill her trouthe. And once she agreed to do so, everything fell into place. It is not a happy ending, but it is a noble ending — and it all follows because Dorigen finally fulfilled her trouthe.

This by itself should pretty well demolish the idea that Chaucer’s ideal was standard “courtly love.” “The second recurrent motif in tales of romantic love is that of secrecy, privateness. Andreas [Capellanus, author of the textbook De Amore] has a ‘rule’ about this: Qui non celat, amare non potest (The man who cannot keep a secret cannot be a lover).”161 But the whole triumph of the plot comes when Dorigen tells Arveragus the truth.

The changes Chaucer has made in this tale are interesting. Many are trivial — among other things, he changed all the names (in Boccaccio, e.g., the Aurelius character is “Tarolfo”162). But there are some which appear to have deep significance. In Il Filocolo the Dorigen character is trying to play “a trick”163 to rid herself of Tarolfo, and simply asks for a garden in winter164 — pretty but not very relevant. In Chaucer, Dorigen instead asks for the rocks of coastal Brittany to be removed — important, because she had worried that Arveragus’s ship would hit them and he would be killed. Even in making her rash promise to Aurelius, she is thinking of Arveragus.165 It is not just a way of getting rid of Aurelius, as in Boccaccio; it is an expression of her love and fear for her husband.166 But she has tempted the fates, and comes close to paying the price: If Arveragus had been less open-minded, or Aurelius less noble, she would have suffered. As it is, trouthe in its sense of nobility or gentleness triumphs.

“[A]s Neville Coghill says, ‘how to be happy though married is not [the Tale’s] true theme. The true theme is noble behavior.’ By noble behavior he means gentillesse… but implicit in this idea of gentillesse is the concept of trouthe, which is another of the Tale’s dominant themes emphasized here by Arveragus and Aurelius in showing their final generosity.”167

Here again we see “philosophical” aspect we observed in The Knight’s Tale: when Dorigen begs that the rocks be removed, “this apostrophe to God… is very similar to Palamon’s questioning of the Almighty in ‘the Knight’s Tale.’”168

Some have questioned the fact that Arveragus, at the beginning of the tale, promises privately to accept Dorigen’s will — and then orders her to keep her trouthe, against her will. I think this misses the point. Had Dorigen known what to do, she would have done it and he would have accepted it. But she is in a dilemma. He insists on what he thinks is right — the keeping of trouthe — and by so doing starts in motion the “eucatastrophe” of the tale.

The four romances we have examined show the full power and range of trouthe as Chaucer saw it. Griselda showed trouthe in her unshakable fidelity to Walter. Dorigen showed it by telling her husband the truth. Palamon and Arcite showed (the failure of) trouthe as integrity of the will and of promises made. And the knight of the Wife of Bath’s Tale showed it by trying to be true to his unwanted wife’s needs.

“Dorigen lauds Arveragus’ gentilesse toward her in refusing to insist on soveraynetee in marriage. Aurelius is deeply impressed by the knight’s gentilesse in allowing the lady to keep her word, and emulates it by releasing her. And finally, the clerk releases Aurelius, from the same motive of generous emulation.”169

The Franklin’s Tale resembles the Knight’s Tale in that it is built around a relationship of equals170 — even if, in this case, the equals are not all of the same sex. The Franklin declares,

Love wol nat been constreyned by maistrye.

When maistrie comth, the God of Love anon

Beteth his wynges, and farewel, he is gon!

Love is a thyng as any spirit free....

Looke who that is moost pacient in love,

He is at his avantage al above.171

Yet we don’t find trouthe only between Arveragus and Dorigen. The relationship between Aurelius and Dorigen is also about trouthe: although he desires her, he also respects her, and so frees her of her promise. Would a lesser man have done that?

“There is just sufficient realism to make the moral solution credible, and the difficult middle road is taken between the purely tragic (which the story so nearly becomes) and the right balance is struck between the worlds of courtly society, Armorik Brittany, commercial Orleans and the land of Faerie.”172

There are plenty of bad marriages in the Canterbury Tales. Both the Host and the Merchant indicate that they have shrewish wives — and the Merchant shows it in his tale.173 But the marriage of Dorigen and Arveragus, despite their little problem, is very happy.174 And all because it is based on honesty, sharing, respect — and a genuine trouthe.

It is hardly coincidence that the Franklin’s Tale almost certainly follows those of the Clerk, the Merchant, even the Wife of Bath. “One need only pause to contemplate what might have been the effect of another sequence of the tales to rejoice that The Franklin’s Tale is the last in the manuscript grouping.175

“We need not hesitate, therefore, to accept the solution which the Franklin offers as that which Geoffrey Chaucer the man accepted for his own part. Certainly it is a solution that does him infinite credit. A better has never been devised or imagined.”176

Image of the Franklin, from the margin of the Ellesmere Manuscript of the Canterbury Tales.